Running alongside his storied career as a comics writer, editor, and publisher, Jim Shooter began a second, parallel career sometime in the 1990s: that of recounting his first career in vainglorious prose and delusional detail. This second career is now going full tilt on his newly created blog, which would be neither here nor there if the fictional portrayal of his first career did not intersect so often with real events in recent comics history, which must therefore become more and more fictionalized to accord with his own disingenuous retelling of his life story. The truth, even any vestigially subjective side of it, is abandoned in the relentless pursuit of self-mythologizing.

There are occasional forays into creative mystagogy, but by and large, his blog is taken up with his autobiographical vignettes — his hardscrabble life in the steel plants (or was it the coal mines?) of Pittsburgh, pulling himself up by his bootstraps when he began working for the comics industry at age 14 (with the occasional helpful tug or two by Mort Weisinger or Stan Lee), and his subsequent climb up the corporate ladder at Marvel, fighting for creators every step of the way, until he became editor-in-chief in 1978. At first, I was prepared to accept this as innocuous pap — until I came upon two recent entries ostensibly describing the dispute between Marvel Comics and Jack Kirby in the 1980s over Marvel’s refusal to return Kirby’s original art. Shooter blogged about his own involvement in this episode, from his insider — and therefore groundbreakingly revealing and honest — point of view. In fact, they were compendiums of falsifications and misstatements of fact that demand refutation. In his April 1 post, Shooter wrote, “I’m the most vilified human being in the world when the subject of Jack Kirby comes up, and it wearies me.” Tell me about it. Jack Kirby’s three-year ordeal to force Marvel to return his own artwork to him (1984-1987) is now a footnote in history, but the truth of it ought to be respected; apparently, constant vigilance is required. (His two posts on the subject can be found here and here.)

Before I get to Shooter’s blog posts, let me briefly summarize the dispute between Kirby and Marvel and the historical circumstances that led up to it (Additional Journal coverage of the dispute by Michael Dean can be found here.). After the Copyright Act of 1976 was enacted into law (formally taking effect in 1978), media companies like Marvel and DC, heretofore dealing with creators under a sloppy but more-or-less de facto work-for-hire arrangement, had to enshrine their work-for-hire understanding contractually. Kirby, who had created and co-created many of Marvel’s mainstay characters — the Fantastic Four, Hulk, Captain America, etc. — was considering returning to Marvel Comics in 1979 after a stint in animation, until he saw their newly drafted standard contract enumerating the rights that he would give up by signing it, which were, essentially, all of them. He went back to animation and published his comics with independent presses (such as Pacific Comics) and refused to work for the major companies under work-for-hire conditions any longer.

Before I get to Shooter’s blog posts, let me briefly summarize the dispute between Kirby and Marvel and the historical circumstances that led up to it (Additional Journal coverage of the dispute by Michael Dean can be found here.). After the Copyright Act of 1976 was enacted into law (formally taking effect in 1978), media companies like Marvel and DC, heretofore dealing with creators under a sloppy but more-or-less de facto work-for-hire arrangement, had to enshrine their work-for-hire understanding contractually. Kirby, who had created and co-created many of Marvel’s mainstay characters — the Fantastic Four, Hulk, Captain America, etc. — was considering returning to Marvel Comics in 1979 after a stint in animation, until he saw their newly drafted standard contract enumerating the rights that he would give up by signing it, which were, essentially, all of them. He went back to animation and published his comics with independent presses (such as Pacific Comics) and refused to work for the major companies under work-for-hire conditions any longer.

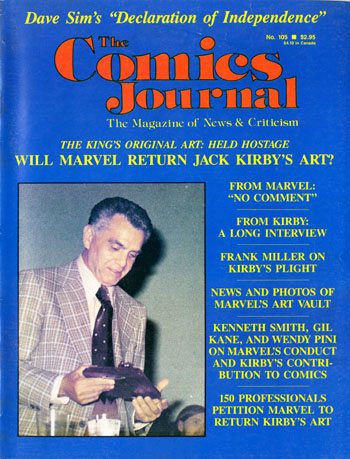

Traditionally, most comics companies never returned original art to the artists. They may have occasionally returned it upon request, but more routinely they kept it in storage, threw it away, or gave it away to fans. By 1976, because of a confluence of historical circumstances, which mostly amounted to raised commercial and creative consciousness among artists, both Marvel and DC were returning original art drawn for their current comics. DC also dug through their archives at that time and returned to the artists all the old art in its possession. Marvel did not until 1984, when, under pressure from artists, they too began to return older original art. But there was a catch. The artist had to sign a one-page “release form” that was a retroactive work-for-hire contract, cementing Marvel’s ownership of the reproduction rights of the art and any concepts or ideas within it. Most artists didn’t have any objections to signing this, or at least not sufficient objections to prevent them from signing it in order to get their original art back (which they could, for example, sell on the then-growing original art market — which was an important economic consideration, insofar as working for Marvel over their lifetimes had impoverished many of them). However, when it came to Kirby, Marvel drafted a special four-page document just for him, and what a document it was. It included many provisions absent from the one-page document all the other artists had to sign, and changed the nature of the “gift” (as Marvel referred to the art). First, it did not cede ownership of the art to him; no, unlike the agreement with all the other artist, which offered to the artist “the original physical artwork,” Marvel only allowed Kirby “physical custody of the specific portion of the original artwork”; in other words, Marvel was allowing Kirby to store the art, but only until such time as Marvel wanted access to it: “Upon Marvel’s request…the Artist will grant access to Marvel or to Marvel’s designated representatives to make copies of the portion of the Artwork in the custody of the Artist.” Kirby couldn’t sell the art since he only had physical custody of it. (There were a raft of other draconian stipulations in the document, but that will give you the flavor.) Adding insult to injury, Marvel was only offering Kirby 88 pages of his art — out of the over 8,000 pages he had drawn! Keep in mind that Marvel didn’t own the art in the first place — they had never actually bought the original art; they paid for the reproduction rights — so they held hostage artwork Kirby himself owned in an attempt to coerce him into signing a retroactive work-for-hire agreement. Kirby received this form in August 1984 and began negotiating with Marvel, requesting a complete list of art (denied!) and asking that a Kirby representative be allowed to catalogue the art in their possession (denied!). The Comics Journal broke the story in July 1985, almost one year later, when Kirby decided to go public, thinking his negotiations were going nowhere.

I felt strongly that Marvel ought to return Kirby’s art and advocated for that in the pages of The Comics Journal for the next two years. I circulated a petition to comics shops that fans could sign on behalf of Kirby; I circulated a petition among professionals; we published news stories chronicling Marvel’s intransigence; and I organized panels protesting Marvel’s treatment of Kirby at various comics conventions throughout the country. The goal was simple: Embarrass Marvel sufficiently by speaking as truthfully and making as much noise as possible; simply tell the truth so that the company would eventually follow the path of least resistance and do the right thing — for PR reasons, if nothing else. It worked for Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster less than a decade earlier when Jerry Robinson and Neal Adams spoke out on their behalf, and Warner finally gave them an annual pension.

Shooter was the editor-in-chief of Marvel Comics at this time and the public face of Marvel, such as it was; he didn’t merely restate the company’s position, but argued vehemently in favor of it.

Shooter’s two blog entries purporting to accurately describe Kirby’s dispute with Marvel are such falsified claptrap that they reminded me of Mary McCarthy’s infamous quip about Lillian Hellman’s writing, made in an eerily similar context — that every word is a lie, including “and” and “the.” There are minor errors, but I’ll stick to the major, more partisan, and morally tendentious misstatements of fact. Otherwise, we’d be here all day.

In his April 1 post, Shooter explains that by the time he became editor-in-chief Marvel was returning new art to artists, but that he had to lobby Marvel execs to return the old art (“I was on the side of Kirby and all the other old artists”). He then states unequivocally, “As soon as he [Kirby] left, he sued Marvel for ownership of the characters he’d created.” This would have been, according to Shooter’s chronology, circa 1979. “So, then,” he elaborates convincingly, “because he was suing Marvel, the lawyers felt that the artwork couldn’t be returned — it’s complicated, but doing so would tend to support his claims. In fact, they wouldn’t let me return artwork to anyone while the case was pending. Imagine the frustration of guys like Joe Sinnott and the Buscemas.” Yes, just imagine. “The legal sparring went on,” Shooter avers. “Starting, as most lawsuits do, with a period of threats and legal maneuvering, in 1978 the Kirby side began an aggressive legal and PR attack on Marvel that ended (or lessened somewhat) in mid-1986 when the matter was settled.”

“Eventually,” he continues, “I convinced the lawyers that it wouldn’t compromise the case if the artists got their art back, and I was allowed to return everyone’s but Jack’s. […]

The Kirby case ended when Marvel, in discovery, produced a number of documents, including several signed with Cadence Industries’ predecessor proving that Kirby had specifically agreed more than once in exchange for compensation (beyond the original payment for the work) that Marvel owned the work (art, characters, everything). One specifically listed every story Kirby ever did -- part of the proof Martin Goodman was required to provide that he owned what he was selling when he sold Marvel to Cadence, I believe. Kirby's lawyers were apparently unaware of the existence of these documents, apologized, and dropped the suit.

Marvel's lawyers would have shown them earlier, but never dreamed that the other side wasn't aware of them.

The only remaining thing was returning the artwork. Kirby then demanded as a condition of accepting the artwork that he must be given sole credit as creator on all the characters he co-created with Stan, and that Stan must specifically receive no credit. He framed his demands for the return of the artwork in such a way that to do so would be a tacit admission by Marvel that it was "his" art, i.e., he owned the underlying rights, and therefore the characters. Kirby also insisted that he created Spider-Man.

“[…] So Jack, with his lawyer’s help, sent us a letter refusing to accept the artwork back unless he were given credit as sole creator on all the old stuff he and Stan worked on together. He specifically insisted that Stan would get no credit, and that Jack must get credit, or Jack would not accept his artwork back. That just blew my mind.”

Notice the casual certainty with which these “facts” are rolled out, the deep knowledge implicit in that certainty, the clear narrative line, the details that add verisimilitude — the “discovery,” part of the legal process where both sides’ lawyers interrogate the principals before a stenographer, the production of specific documents, such as the one that proved Kirby signed away his rights numerous times or the one that proved Goodman owned all the art in the first place. What a memory. Shooter even recalls that Kirby’s lawyers apologized to Marvel once Marvel provided these devastating documents and dropped the suit. It was only then that Marvel allowed Shooter to return Kirby’s art, but Kirby, being a perennial troublemaker, caused even more delays by making crazy demands — he wanted to be listed as sole creator on characters he only co-created, for Stan Lee receive no credit whatsoever (a particularly petty demand, but that was clearly the kind of guy Kirby was) — and so on. Kirby even refused to accept his own artwork if Marvel didn’t accede to this demand. This was so crazy that it was no wonder it blew Shooter’s mind!

I can’t say whether Shooter’s mind was blown at this or any other time, but I can say with absolute certainty that nothing else in this scenario is true. That’s right; Kirby hadn’t sued Marvel. There was no lawsuit, no discovery, no documents produced, no legal maneuvering within a lawsuit, no demand by Kirby, enshrined in a lawyer’s letter or otherwise, that he receive sole credit for characters he co-created, and no demand that Lee receive none. It’s all a fiction. None of this happened.