EDITORS

GROTH: Who was in charge of your division? Did you have an editor who was always lurking about?

ROBINSON: Yeah. Whit Ellsworth was my editor. Then the other editors were right in a row. Right next to him was Murray Boltinoff, Henry’s brother (also a cartoonist), and Jack Schiff and [Mort] Weisinger, and then a few others from time to time — Al Bestor, for one — but they were the perennials.

GROTH: Would they sit with you guys or in a separate room?

ROBINSON: We were literally in one room. It was quite intimate. There was just really an aisle separating the editors from the artists.

GROTH: And how was it broken down? Did each editor have his own books?

ROBINSON: Yeah, more or less. They had responsibilities for their own books, the writing. I just dealt with Whit. I didn’t deal with anybody else in terms of the art. I had nothing to do with the other editors. The editors were in charge of the writing.

GROTH: Tell me a little about Whit Ellsworth. What was he like to work with professionally?

ROBINSON: I liked Whit. I got along very well with him. I think he appreciated what I did, and the enthusiasm I brought to it. I guess I was young and eager, and he gave me my head. If I had an interesting cover idea, I would show it to him and he might make a suggestion or two, but a lot of times I didn’t even show it to him until it was finished. He wasn’t very demanding, and I think that allowed for a lot of growth and a lot of experimentation. He didn’t try to impose himself upon the work as I think some of the other editors tried to do on the scripts.

Whit was a cartoonist himself before.

GROTH: I was going to ask you where he came from.

ROBINSON: I don’t know what other jobs he held. He was kind of a bigfoot gag cartoonist. Maybe that in part was why he gave us our head, or at least in my case. Superman and Batman were the two big features so he certainly looked at everything carefully. But he never really interfered, as I say, with the drawing because he was not an illustrator. Maybe that was part of giving me my head.

GROTH: What did a good editor do? Did a good editor basically just leave you alone, or did he provide guidance?

ROBINSON: There’s a fine line between giving you wide latitude and giving guidance and inspiration.

GROTH: Was he observant, do you think?

ROBINSON: Oh, yeah. I think he was observant, and I guess whenever there was something important to exercise, I think he did. He certainly had the authority, and he had my confidence. The only one above him at that time was Liebowitz.

GROTH: Did the artists discuss among themselves the relative qualities or deficiencies of the editors?

ROBINSON: I’m sure they did more with the script editing. There was just one art director, which was Whit ... So there wasn’t much discussion about that. I’m sure it was more about the editing with the writers.

There was a lot of tension between Mort Weisinger and Schiff and the writers, basically.

GROTH: Between the editors and the writers?

ROBINSON: Yeah.

GROTH: What was the source of that tension?

ROBINSON: Well, these guys were very experienced editors and writers. They came from the pulps, mostly, and a lot of the writers had lesser résumés. However, they knew the comics. I think that was the basis of some of the tension. The editors thought that they were much more experienced writers, they knew all of the nuances, but in dealing with somebody who really knew what he was doing, like Bill [Finger], that was unfortunate.

GROTH: Did you get to know anything about Murray Boltinoff or Mort Weisinger as editors or as professionals?

ROBINSON: Mort was very exuberant, very outgoing ... Might be a little bit more on the loud side, if anything. Kind of ruddy complexion; and kind of burly. He was good. He was very clever. He was creative. But he was very hard. Like around Bill, I saw him unmerciful at times.

GROTH: I understood he could be quite a bully.

ROBINSON: Yes, he could. And Jack was a sweeter guy. But he also could be tough, and even cruel. Maybe he thought he had to follow Mort’s lead.

GROTH: Now, do you think that toughness was justified, or do you think it was excessive?

ROBINSON: Well, they were professionals and very creative guys; Mort more so than Jack, from my own experience. Maybe they molded some young writers and helped them. But you know, there are all [different] methods of doing that. They weren’t the easiest to work with. They could be cruel.

JAMMING ON PAGES

GROTH: Did you enjoy working among artists as opposed to alone in your own studio?

ROBINSON: I did enjoy very much working there, because I never knew any artists before. I never saw any artists work before. There was a lot of camaraderie there. The artists got along famously, and I think we all added something to our development. I think we were all influenced by one another to some degree.

GROTH: I gather there was a lot of professional camaraderie, where you could discuss professional issues and issues of craft and so forth, among each other?

ROBINSON: We were doing that all the time: the storytelling ideas, ways of conceiving techniques and how we visualized. I’m sure, walking down the row of drawing boards to see Mort Meskin penciling and then Jack Kirby, Joe Shuster, Fred Ray and myself, there were a lot of different styles and approaches. We would look at each other’s work and sometimes we’d jump in on each other’s work. I remember doing some covers with Simon and Kirby, and a lot with Fred Ray. Of course Mort Meskin became my partner later, but even before then we’d do some things together at DC.

In fact, I have a page in that exhibit in Atlanta — a splash page that I happened to save because it was one of the fun things that we did. I think it was Johnny Quick. Mort was doing a layout of a splash page, and I was watching him, and he was drawing a figure of Johnny Quick, and he was going to put some gangsters standing watching him fall. So he said, “Say, Jerry, you do great crooks. Why don’t you put in the crooks for me?” Which I did, and then I kept that page, because it was funny.

GROTH: When you were working at the DC offices, were you on salary?

ROBINSON: Part of the time I was on salary, and part freelance.

GROTH: And then you were paid per piece?

ROBINSON: Yeah, I think it was page rate or story rate, as I recall.

GROTH: I was curious when you were there, from ’42-’46, how the work was allotted. I went through one of the DC Archives books of Batman and I couldn’t detect any pattern as to the actual work you did. Let me give you an example. This is from Detective. The March 1943 issue, you inked the main story. In the April ’43 issue, you penciled it. In the May ’43 story, you didn’t do anything. In the June ’43 story, you did pencils and inks.

ROBINSON: The April ‘43 issue I did both pencils and inks, except for a couple of pages.

GROTH: July, you didn’t do anything. In August, you are credited with drawing “large heads.” This is volume three of the Batman Archives.

ROBINSON: I wouldn’t take as gospel all of these credits, by the way.

GROTH: OK. It’s good to know that. I don’t want to dwell on large heads, but I thought that was a peculiar annotation. Then in September, you did both pencils and inks. It ranged all over the place.

ROBINSON: Yeah.

GROTH: You did inks, you did pencils, you did both. You did large heads. So I’m kinda wondering how you were allotted the work in such a way that it was so inconsistent?

ROBINSON: Assuming the credits were correct, that wouldn’t surprise me. What would happen is that a script came in that I was given or suggested I would like to do. Those I penciled I would usually ink myself. That’s what I preferred to do, both pencils and inks. In the meantime, Bob was still doing Batman scripts that he had roughed out, and I would finish it. I would ink it or finish the pencils and ink and George would do most of the backgrounds. There was really no rhyme or reason other than what was on the table to do. I mean, they didn’t plan that I was going to do so many stories in this issue or that I would do this story and that he would do another one and so forth.

GROTH: You were basically told, “This issue you’re penciling. Next issue you’re inking.” Whatever came down ...

ROBINSON: Well, it was almost not by issue but by story. They put the stories together to make an issue. I remember one issue of Batman was all my stories. Another issue I might have one. It depended on what I’d finished. I would try to do the covers whenever I could, because I enjoyed the covers and strived for new ideas — and design concepts — and Whit wanted me to do the covers.

CHARLIE BIRO

GROTH: When you were working there, did you do work other than on Batman?

ROBINSON: Later on I did. I moonlighted. I got kinda tired of Batman. Notably when we started Daredevil with Charlie Biro and the Wood Brothers.

GROTH: Let me try to get a chronology of where you went. You also drew the Vigilante and Johnny Quick with Mort Meskin?

ROBINSON: Right. That was later.

GROTH: Would you have penciled, inked or both on those?

ROBINSON: Really, we did both. That was kind of the fun of it. Whenever one felt like penciling and the other felt like inking. It gave us great variety. When Mort and I got together later and opened our own studio on 42nd Street, then we inherited the features Mort was already doing. He had started Vigilante and Johnny Quick.

GROTH: Those were for DC, weren’t they?

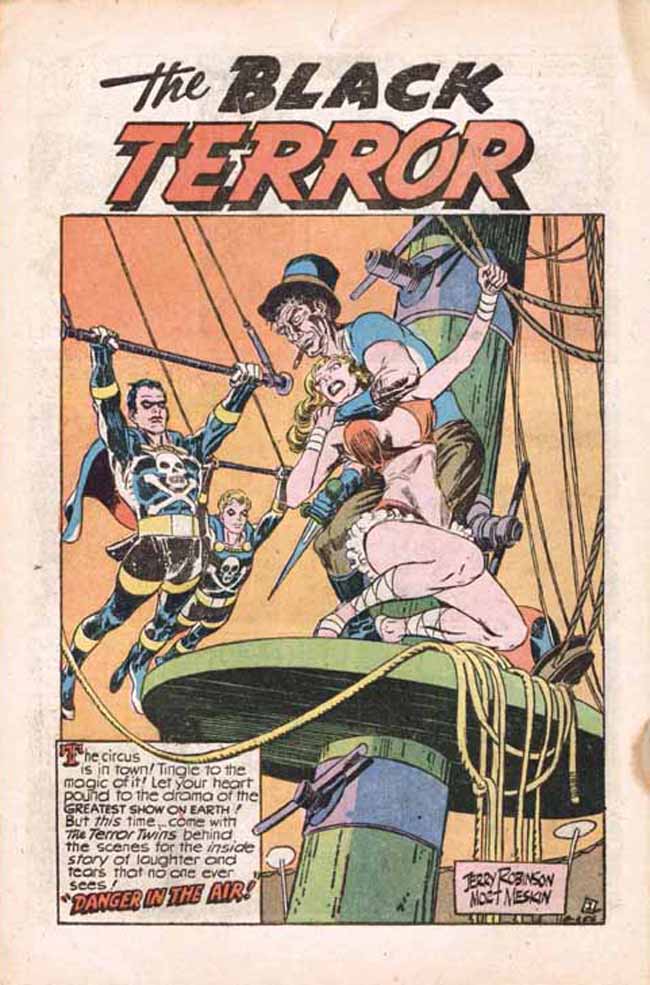

ROBINSON: For DC. Yes. So then we took on the Black Terror and Fighting Yank [Nedor characters] for Standard as well. So we were doing those four main features. Then occasionally we’d do some other things. I remember we did some work for Simon and Kirby when they had their studio. We did some science fiction and mystery and romance.

GROTH: Now the Vigilante, Johnny Quick, Black Terror and Fighting Yank ... would this have been after your Batman stint? After ’47?

ROBINSON: Yes. Definitely.

GROTH: Now you started a little studio with Mort Meskin in your apartment basically?

ROBINSON: No. We had a studio on 42nd Street.

GROTH: Oh, you did. A separate studio.

ROBINSON: Yeah, just off Sixth.

GROTH: Why did you leave Batman?

ROBINSON: I wanted to do other things. I wanted to do something in my own name and write more. That’s when I started London for Daredevil. After that ...

GROTH: Can you tell me approximately when you started working for Charlie Biro?

ROBINSON: Well, it was published by Lev Gleason.

GROTH: When would that have been?

ROBINSON: Well, it was while I was working on Batman. We started Daredevil early in ’41, before we got into the war. I know I created London as my hero while London was under the blitz.

GROTH: So you were actually working for Lev Gleason and under Gleason for Biro while you were doing Batman?

ROBINSON: That’s correct.

GROTH: So you would have been doing that sort of after hours?

ROBINSON: Yes. [Laughs.] On weekends and nights.

GROTH: Did DC care whether you did that?

ROBINSON: No. In the beginning, I did other things under phony names, as I did on The Green Hornet, because we thought that they were going to object more. They probably never even saw it. I don’t think they surveyed every last issue that was being published. Whether they did or not, we never got any feedback.

GROTH: Charlie Biro was something of a pioneer with Crime Does Not Pay, which began in 1942 but really hit its stride in the ‘50s.

ROBINSON: That’s right.

GROTH: But can you tell me a little about him as an editor? Was he your editor on Daredevil?

ROBINSON: He wasn’t my editor. I guess technically he produced the book, but we all did our own thing on that. He wouldn’t see anything until I wrote it, drew it, and handed it in. I knew Charlie very well. We knocked around together. He was a very, very creative guy.

I don’t think enough has been written about Charlie. He did a lot of very innovative things. I relate him to Stan Lee, in some respects, as an entrepreneur. He was very creative, very versatile, and a fast writer. He did a lot of his own writing and drawing. He was equally good at both. And he was, I think, a good producer. When I was at Gleason, Daredevil was kind of a separate entity, but I saw a lot of Charlie and the Wood brothers, both at work and socially. Charlie was kind of a gadabout. I don’t like to write about their personal lives, but he did fool around a lot, even though he was married to and loved a beautiful, delightful woman.

GROTH: My understanding of Biro’s innovation in comics was that he imposed a kind of realism or naturalism in the Crime Does Not Pay comics. Is that your take on it?

ROBINSON: He did. He had a good popular feel for properties and he knew how to make the most of them. I think he was maybe the first, even before Stan, to establish a personal rapport with the reader. He would add personal things, clubs ... I forget all of the stuff he did, but he was very creative.

I first met Charlie I think when he was at MLJ, with Bob Wood, the oldest brother. I met them through Bernie Klein. I came down to MLJ one day to visit him and that’s when I met Charlie Biro and Mort Meskin and Bob Wood. I think Irv Novick was also there. So Bernie and Mort and I became a trio. We were all living separately so we decided to get an apartment together. I brought Mort up to DC. That’s how he came from MLJ to DC. And then I brought Bernie up.

GROTH: I gather that Biro was probably older.

ROBINSON: Yeah. I think he was a few years older.

GROTH: He was on staff at MLJ at the time?

ROBINSON: Well, I don’t know what his working relationship was. He was either on staff or freelance but he was working there.

GROTH: And then he moved to Lev Gleason.

ROBINSON: Uh-huh.

GROTH: Tell me who Lev Gleason was.

ROBINSON: I didn’t get to know him very well. I only met him a couple of times.

GROTH: Basically, he was an entrepreneur, I assume?

ROBINSON: Yeah. I heard some very good things about him, subsequently. He was a very progressive. That’s what I understand, but I can’t fill you in on his background.

GROTH: But you essentially worked for him?

ROBINSON: Essentially, as a freelancer.

GROTH: I assumed that he behaved professionally and paid you and so forth?

ROBINSON: Oh yes.

GROTH: Which not every comics publisher, I understand, did.

ROBINSON: Right. No, he did. Gleason was professional. Later on I worked at Crestwood.

GROTH: Kirby worked for Crestwood.

ROBINSON: Yes. Right. So did Lou Fine and a few other very good people. I did a feature called Atoman. We did two issues, which I wrote and drew. I was in Florida drawing the third issue, basking in the sun. And I got a phone call. I guess it was from Mort.

He asked, “What are you doing?”

I said, “Oh, I’m in the middle of penciling the third story of Atoman.”

“Well,” he said, “you can just stop. They just folded. You’re not going to get paid.” So I was stranded in Miami.

GROTH: Well, I guess there are worse places to be stranded.

ROBINSON: Right.

GROTH: So you worked for Biro and Lev Gleason, freelancing drawing London in Daredevil while you were doing Batman?

ROBINSON: Right.

GROTH: Who wrote London?

ROBINSON: I wrote London.

GROTH: You wrote, drew and inked it?

ROBINSON: Yes, I did everything. Maybe somebody jumped in to help ink a page or so — but I did 95 percent.

GROTH: And it was purely on a freelance basis?

ROBINSON: Yes.

GROTH: Do you remember what you got paid back then?

ROBINSON: God, no. That’s a good question. I don’t know. It was probably around $25 or $30 a page, something like that. I remember when I started Atoman, Ken Crossen enticed me over because he paid me $50 a page, which was considered really phenomenal at the time.

GROTH: No wonder he went out of business.

ROBINSON: [Laughs.] I don’t think that was the reason. He didn’t have distribution.

FREELANCING

GROTH: When you quit DC, which was approximately ’47, did you basically go freelance from then on?

ROBINSON: Oh, yes. I never worked on staff for anyone else. In fact, I went off staff on the last part of the time I was at DC.

GROTH: Tell me a little about how you collaborated with Mort Meskin. First of all, who would write the strips?

ROBINSON: We didn’t write them.

GROTH: You were given scripts?

ROBINSON: I can’t remember who the hell did the scripts. They were pretty well done. I think Mort Weisinger might have edited the Vigilante and Johnny Quick scripts. Either Mort or Jack [Schiff].

GROTH: And you and Mort would figure out who would break them down and do the penciling and inking?

ROBINSON: Right. We would do it story by story, and sometimes even in the middle of the story.

GROTH: Did both of you enjoy doing every facet of it?

ROBINSON: Oh, yeah. I mean, that’s why we switched around, penciling and inking. We experimented with different techniques and innovated. I remember one time we decided to work from parchment: pencil on paper and put it in a light box and just ink on parchment because we liked the effect. Things like that.

GROTH: Can you enumerate the strengths and weaknesses of the two of you? Did Meskin have any weaknesses?

ROBINSON: Uh ... Outside of women, you mean?

GROTH: [Laughs.] No, including women.

ROBINSON: We all have that.

GROTH: I was going to say, I would assume that was standard.

ROBINSON: I don’t know. He had very few weaknesses. He could draw anything. He was a great composer, storyteller, and he could ink beautifully. He liked my inks, but I think he inked equally as well. He had a different kind of touch. We seemed to blend very well. We thought alike and personally we ... Well, we were best friends and shared an apartment, so it was a close relationship.

GROTH: You did the Black Terror and Fighting Yank for Standard. Can you tell me a little about Standard?

ROBINSON: No. I can hardly tell you anything about them. We hardly ever visited them. We’d do the work, and we hated to even go over there. We’d have someone drop off the finished work and pick up the scripts. We had nothing to do with the editors. They never saw it until we were finished. I mean, we had a reputation at the time. I think they were just happy to have us do the work.

GROTH: So no personal relationship to speak of?

ROBINSON: No.

GROTH: At some point you worked for Simon and Kirby. How would that come about? Would you just have gone to Simon and Kirby and said, “I’m available?”

ROBINSON: I don’t remember how we connected up. We were already doing these four major stories each month, so that was a lot of work. I guess if we had any time to fill in, we let them know we were available. I knew Jack from DC, and I knew Joe as well, so it was probably very natural to call them.

GROTH: How did you know Joe?

ROBINSON: From his work at DC. He was doing features with Jack ... Manhunter and some other features ... Boy Commandos.

GROTH: Would they give you scripts to draw?

ROBINSON: We’d get the scripts from them.

GROTH: Do you know who wrote the scripts?

ROBINSON: Let’s see. I did a feature that was written by Joe Green. It happened that his son had some work of his that we borrowed for the Atlanta museum exhibition. But talking about scripts, one thing I unearthed ... I think it’s the only existing script by Bill Finger. The actual script is in the show in Atlanta. It even has his home address on it, and editing marks either by him or by Weisinger or whoever edited the script. It was one that I drew. That’s why I had it. I just stuck it in a drawer, and somehow that survived.

GROTH: What were the features that you did for Simon and Kirby?

ROBINSON: They weren’t features. They weren’t continuing characters. They were individual stories: science fiction, mystery, romance, a variety of subjects. I worked for Stan Lee for almost 10 years doing the same type of thing.

GROTH: Simon and Kirby were a shop and therefore an intermediary between you and the publisher. Correct?

ROBINSON: Right.

GROTH: Why would you not have gone directly to the publisher? In other words, why did the publisher need an intermediary like that when you obviously would have worked directly for him as you worked for DC?

ROBINSON: Well, I presume it had the same advantages for any publisher: They didn’t have to do the production work and have somebody who knew the artists and the writers, put them together, were responsible for getting the book out and didn’t have the overhead of doing that. Sure, we could have gone right to any publisher, but we knew Joe and Jack and so I guess that’s why we naturally went to them. They may have even approached us. I don’t even recall, because Mort and I were already known as a team. I assume that’s part of their job, to get talent.

GROTH: As an artist, it would have been more to your advantage to work directly with the publisher because obviously the middleman takes a cut.

ROBINSON: Yeah. But maybe [the publishers] weren’t dealing with the artist individually. I don’t recall, but that’s possible, too. Some of the publishers only dealt through the shops who produced the books for them. I don’t know of any major ones, actually, that did both offhand.

GROTH: DC did not?

ROBINSON: No. Timely did not.

GROTH: When did you start working for Stan Lee at Timely?

ROBINSON: Probably in the early ’50s. I was also teaching at the School of Visual Arts. That was when I was young and foolish. I worked through most of the ’50s there.

GROTH: I assume you simply walked into Timely and introduced yourself?

ROBINSON: No. As a matter of fact, my first meeting with Stan was while I was teaching at the School of Visual Arts. I taught there in the evening from 6:00 to 10:00, mind you, four hours. That was after doing my own work all day. The school was founded by [Burne] Hogarth and Sy Rhodes. You knew Hogarth so well, you probably knew about that story.

GROTH: Oh, yeah. More than I can say.

ROBINSON: Yes. That’s how I first met Burne, also. But at any event, talking about Stan ... In my class I would invite some top people down to talk to the class, editors or artists and so forth, which was interesting for the students to meet and hear different points of view and what they were looking for. So I invited Stan down one time. I didn’t know him. I just called and invited him down and he came down to talk to the class. At that time we got to know each other. I guess he knew of my work, and that’s why he came. So while we were there he said, “Why don’t you come up and work for Timely for me some time?” It was his invitation. I had an opening to do some other work, so I started that relationship, which lasted quite a long time. And I did a lot, quite a lot of art for Timely at that time with Stan.

GROTH: Now you would work full script, I assume.

ROBINSON: Basically, yes. I always felt free to change or alter sequences if it didn’t work visually, but yes. They were full scripts.

GROTH: Did you work directly with Stan Lee? Was he your immediate editor?

ROBINSON: Yes. I worked with him.

GROTH: What was he like as an editor in the ’50s?

ROBINSON: Well, he was the kind of editor I liked. He didn’t give me any problems.

GROTH: Left you alone.

ROBINSON: He left me alone. I picked up a script. I’d draw the whole thing, finish it, pencil and ink, bring it in. He’d look at it and say, Great, Jerry. Here’s the next one. I mean, we had some interchange of course. But basically that was it.

GROTH: Are there any illuminating anecdotes or idiosyncrasies that you can recall about how he worked or what he was like professionally at that time?

ROBINSON: Oh, I always found Stan very likeable, always enthusiastic and made you feel comfortable. He was easy to work with. We had fun and we laughed a lot. I think basically he liked what I did. I know in recent years he’s been very laudatory about that period. He probably sees it through a haze. He once said to me, “You should have been a top illustrator. You were too good for us.” He was being kind. But I think he liked what I did, obviously. And I enjoyed working for him. What I enjoyed most of all was the variety. See, this is what I hungered for. As a good editor, he let me do what I liked — and did best.

GROTH: So if you could work on different genres...

ROBINSON: Yes. And I could handle each one the way I felt the story was best handled. They didn’t look alike. The war didn’t look like the science fiction or the crime and so forth. At least, that’s what I would try to do: Do the story in the manner that the story would be best told.

GROTH: There’s one book I wanted to ask you about, which you mentioned earlier had been written by Don Rico. That was a war book called Battlefront, which you did in 1952. I think you did at least four or five issues of that. How closely did you and Don Rico work on that?

ROBINSON: I didn’t work closely with him at all. In fact, I don’t even remember meeting him.

GROTH: So you would just get a script?

ROBINSON: I’d get the script. Stan was a good editor, and I think that he had confidence in what I was doing. I felt free to alter scripts or tighten the drama, improve the pacing of a sequence or improvise. I never just copied it literally from panel to panel. Although, if they were good writers, like Don was, there was probably less to do in that regard. I think he was a pretty good visual writer as well, in the tradition of Bill Finger.

GROTH: These seemed like some of the better scripts that you would have worked on. Were you influenced at that time by Harvey Kurtzman’s war books, which were coming out at that same time? Do you remember?

ROBINSON: No. I don’t think so.

GROTH: What’s interesting is that the first issue of Battlefront contained a series of Korean War stories, and literally two or three months earlier Two-Fisted Tales came out, which was devoted to the Korean War.

ROBINSON: I didn’t remember that they were also about the Korean War.

GROTH: Yeah. It was Two-Fisted #26, which was their special Chiang-Jiang Reservoir Issue. It dealt with much of the same fighting that your first issue did. I was wondering if you had been influenced by that?

ROBINSON: No. I don’t even know if I saw it at that time. You said a couple of months before that?

GROTH: Two-Fisted was dated March/April and Battlefront is dated in June.

ROBINSON: May/June, so it’s a good two or three months. Battlefront must have already been in the works. Stan, if anything, saw the genre developing. I don’t think I knew much about what other companies were developing. I was too busy teaching and doing my own assignments. I did many other war titles, even before Battlefront.

TEACHING COMICS

GROTH: Can you describe how you evolved artistically from the ’40s into the ’50s, how you improved your craft, what you concentrated on and what you ...?

ROBINSON: I don’t know. I did make big jumps. The only thing I can attribute it to is just doing a lot of drawing. I really worked hard and enjoyed the work and tried to do different things, innovative techniques. I don’t know if this is true or not, but now I think my teaching was an important factor. The years I taught, I think I learned more than at any other time. I learn by doing. In teaching, in order to articulate and demonstrate what I was doing, I had to analyze what I was doing, and figure out why, which I learned only through blood and sweat. I learned a lot in the process, and I think the work reflected that in my trying to analyze my thought processes.

GROTH: What exactly did your cartooning course entail?

ROBINSON: I don’t remember what I called the course, originally. It was a little more comprehensive than just the usual cartooning class, as I recall. I don’t know if it was there or at the New School or Parsons, where I also taught, the course was listed as Cartoon Illustration. I taught writing at the same time. I felt that the students should know story construction. If they didn’t have the ability to write their own scripts, I felt they should know the mechanics of writing and to be able to evaluate a good story and to be able at the least to collaborate with a writer successfully. I thought that was an important part of the course. So I taught writing just as if I was studying at Columbia — of course, simplified and focused on continuity and comic-book approach.

GROTH: And of course writing for comics is far more idiosyncratic than writing prose.

ROBINSON: Exactly. Then of course I also included more straight illustration, as well as conventional cartooning. I thought they should be able to do both. And the mechanics of drawing. I included actual life classes, as well as courses in composition, perspective, anatomy, drapery, hand, head, and so forth.

GROTH: Would this have been a standard nine-month curriculum?

ROBINSON: Yeah. The course was five nights a week from five to 10.

GROTH: Five to 10. My god!

ROBINSON: Yeah. So it was a long day for me, because I would be doing my own work during the day and quite often come back at 11 o’clock and pick up the pen and brush again if I was on deadline, as I usually was.

The idea of SVA was that the faculty was made up of working artists in the field, so the teaching wasn’t theoretical. That’s why it appealed to me. I could do my own work, in fact that’s what they wanted. The faculty, all professionals, knew exactly what was happening in the field so we had an excellent record of placing people. We were able to fill the need and know where the openings were.

GROTH: Did you work such long hours then because you enjoyed it and felt compelled to or more because of financial reasons?

ROBINSON: No. I enjoyed it. I enjoyed teaching. The money was minimal. Thinking back, it was a way of taking art courses myself. I had never studied art. So in the teaching process, I really learned a lot. What you have to do, as you might imagine, is understand the creative process you go through in translating an idea into pictures — and also how you learn to do some things just through trial and error, and repetition and the learning process you do on your own, and to then be able to convey that to a student. I had to really analyze what I was doing, as you would never do otherwise.

GROTH: Because most of what you did was intuitive.

ROBINSON: To some extent. There was also give and take with the students, so I enjoyed it. But I was young and foolish, too, for working that much.

GROTH: Well, that’s the time to do it. In 1950, you would have been about 27 or 28. A fairly young teacher, actually.

ROBINSON: Yeah, but I had already been in the field ten years by then.

GROTH: Let me ask you about a few of your students. You had Pete Hamill in your class.

ROBINSON: Yes.

GROTH: Hamill went on to become a first-rate journalist, a novelist. And ...

ROBINSON: He had ambitions to be a cartoonist early on.

GROTH: I know Pete a little bit. I know he loved the newspaper strips. People like Milton Caniff. And of course he knew Burne.

ROBINSON: He also took other classes. I think he was in Burne’s class as well.

GROTH: But he actually wanted to be a cartoonist?

ROBINSON: Yes, that’s what I always understood. He’s mentioned that over the years.

GROTH: How well did you get to know your students? For example, did you get to know Hamill well?

ROBINSON: Not really in depth at that time. I’ve known him over the years. One morning in 1978, I got a call from Pete. He said he just got a review copy of my biography, Skippy and Percy Crosby. I think it was some of my best writing. He was on vacation and had just finished reading it, and liked it so much that he wanted to write a blurb for it — which he did.

I am so proud of Pete’s words. Please allow me to quote him:

"Percy Crosby is one of America’s forgotten geniuses, and Jerry Robinson has given us a superb portrait of the man and the artist. It is not only the best book ever written about any cartoonist, it is a book that plunges into the underground river of tragedy that is part of the American dream."

I don’t think Pete was in the class more than one semester or so, so I didn’t get to know him very well during that time.

GROTH: You probably couldn’t evaluate his performance.

ROBINSON: Not really. No. I had sometimes over 30, sometimes 40 in the class. It was a booming time at the School of Visual Arts.

GROTH: That’s a big class.

ROBINSON: Yeah. Very big. Had to give individual instruction as well as lecturing and so forth. It was hard work at the same time.

GROTH: One of your most prominent students was Steve Ditko.

ROBINSON: Right.

GROTH: Can you tell me a little about what he was like as a student?

ROBINSON: Steve was, as he’s been over the years, very quiet, almost a recluse. He was the same as a young man. He was very intense, quiet, reserved. He was very diligent. He really worked hard. He was very attentive. I know I would like to give him personal criticism because he seemed to understand and absorb it.

GROTH: Was he receptive?

ROBINSON: Yes, very receptive. I knew that he had unusual talent.

GROTH: You could tell even then?

ROBINSON: Yes, because I arranged for him to get a scholarship for the second year, so he was with me for two years. I don’t remember how many scholarships I was able to give, but it was very few, maybe two or three a year at the most, maybe less. I did propose him for a second year, which indicated he was somebody who was going to benefit from it.

GROTH: Now a scholarship would have been given for two reasons: one is that they were good artists and the second is that they probably couldn’t afford it on their own?

ROBINSON: Yes. The financial end was not my business, although I usually would know the financial status of the students after a year. Of course, if they didn’t have any financial need, I assume they wouldn’t qualify for a scholarship. I recommended them on the basis of the ability and those that I thought would benefit from the second year.

GROTH: Accepting a scholarship would indicate that he had not yet become a follower of Ayn Rand.

ROBINSON: I guess not. Not likely.

GROTH: Did it look like he had a lot of natural talent coming in?

ROBINSON: Yes, I recognized it in his first semester. What was just as important to me as the natural ability was the desire and dedication. I’ve seen many kids, who seem to have great natural ability but frittered the time away, didn’t really work hard. It doesn’t matter how much ability you have: You have to do a lot of drawing. You can only learn to draw by drawing. That meant as much to me. I could see his dedication. He worked hard.

GROTH: Nothing can replace commitment and passion.

ROBINSON: Exactly. And he had that.

GROTH: Another artist with whom he later collaborated was Eric Stanton.

ROBINSON: Oh, yes.

GROTH: Was he in your class?

ROBINSON: Yes. For some time.

GROTH: What kind of a student was he?

ROBINSON: I don’t recall if he got a scholarship, but he was with me some time. It could have been a couple of years I’m pretty sure. He was also very talented. Maybe at times he looked to be more advanced than Steve.

GROTH: Were they the same age, roughly?

ROBINSON: They must have been very close in age. Stanton might have been a year or two older, if I were to make a guess. They were both young.

GROTH: Ditko must have been somewhere around 19 or 20, based on your age and his age.

ROBINSON: I would guess that, maybe even a year younger ...

GROTH: Now, Ditko and Stanton shared a studio in the ‘50s. I don’t know if they shared that when they were students with you?

ROBINSON: I don’t think so. I think they got together later, but they apparently met in our class.

GROTH: Stanton went on of course to do bondage comics and illustrations. Ditko was sharing his studio and I believe they collaborated on some of that material. Did you know them when they had a studio together, after they left your class?

ROBINSON: No.

GROTH: Was Stanton into drawing girls in your class?

ROBINSON: Yes. He was already into the bondage.

GROTH: Really?

ROBINSON: Yes. I remember I tried to wean him away from that and to draw other things as well. I felt that was going to hinder his career if he was just known for bondage. He may not get other kinds of assignments.

GROTH: Little did you know.

ROBINSON: Yes. Little did I know ...

GROTH: So that was a commercial as well as an aesthetic consideration on your part?

ROBINSON: Yes, it was. I thought he shouldn’t just be identified with that as he later became.

GROTH: But he was clearly preoccupied by it even then.

ROBINSON: Oh, yes. Definitely, and he was good at it. He was very inventive — a decided asset for that field! Eric was a creative artist with excellent career prospects.

GROTH: Well, like we said, nothing can replace passion.

ROBINSON: Yeah, he had a passion for that.

GROTH: Don Heck was also a student?

ROBINSON: Yes. He was another good student.

GROTH: I would say he was more from the Caniff school of illustration.

ROBINSON: As compared to the other two, yes.

GROTH: Do you remember anything about him?

ROBINSON: Just again that he was one of the superior students. He did very good work and showed good promise. I’m almost positive he’s one of those I got work for earlier on to break into the field. I also taught lettering, not that I was an expert letterer by any means.

GROTH: You could teach it even if you couldn’t do it.

ROBINSON: Well, I’d lettered Batman. I started doing the lettering as well as inking at the very beginning. The lettering must have been pretty crude. Once I learned that there were pens for lettering, and different thickness of pens. I was so naïve. I didn’t even know that there were — jeez, I can’t even think of the name for them now. You know, with attachable tips that are various widths ...

GROTH: Rapidograph pens?

ROBINSON: Not Rapidograph. Speedball, I think. I didn’t know they existed. So for a while every time Batman was mentioned [in a balloon] requiring thicker letters, I’d have to fatten up each letter with a thin Gillotte 290!

GROTH: And you would try to get your students jobs with the companies?

ROBINSON: That’s right. I learned that lettering was a good way to get their foot in the door to meet the editor, to work on professional pages. And they needed letterers, as well as the other specialties.

GROTH: I assume, of course, that you would only try and place the best students. So who would they be?

ROBINSON: Well, I would place the students as they showed proficiency in anything, or at least was able to do a credible job. They had to be on somewhat of a professional level. If they were adept at inking, for example, then they could get a job inking. If not figures, backgrounds. If someone showed ability in one area, I would concentrate in bringing them up to snuff in that specialty so that they could start to get some work. Then they usually would blossom in the other phases of the work. That’s how we got them started in the field. I remember one year, the sum total of all of the kids in the class made over $30,000 in the year.

GROTH: That’s a lot of money.

ROBINSON: For some, it paid their way through the school.

There were many others that went on to have careers that didn’t reach the success of Ditko, but were also excellent artists — Jack Abel and Marie Severin, for example. They worked for years in the field. Several others were successful in magazine cartooning, notably Mort Gerberg in The New Yorker and in newspaper syndication; Stan Lynde, who created Rick O’Shay; and Fred Fredericks, who illustrated Mandrake the Magician for Lee Falk. Both Stan and Fred were exceptional talents. Lee, by the way, was one of my closest friends for about 50 years.

There were others who did quite well in the comics. Among them was Bob Forgione, who became my assistant and later partner — he became vice president of one of the largest advertising agencies in New York; Steve Flanigan, who also became my assistant and partner, now an art director for a major publisher and a fine painter exhibiting in New York; Jack Abel, who had a long career in comics; and Stan Goldberg, a star at Harvey and Archie Comics.

GROTH: I don’t have a date handy, but I believe the school was started in ’47, if I remember correctly. It was a post-war G.I. Bill financed project.

ROBINSON: Right. I don’t know if it was started just with the G.I. Bill — certainly that’s what made it successful.

GROTH: I remember that Burne told me that a lot of G.I.’s used the G.I. Bill to finance their education there.

ROBINSON: Right.

GROTH: So how did you come to meet Burne?

ROBINSON: Well, this was kind of accidental too. So many of these things are accidental, when you think back in your career. I don’t know how Mort [Meskin] learned about the school or was hired, but when I got together with Mort, when we opened our own studio, he was already teaching at what at that time was called Cartoonists and Illustrators. It was renamed the School of Visual Arts a few years later. I remember we had a big faculty meeting deciding what to rename it. So it was then Cartoonists and Illustrators, and it was on the Upper West Side. Mort invited me up to talk to his class one day, which I did, and it was kind of fun. Later on Mort had periods of depression and illness and couldn’t continue the class, and he asked if I’d consider taking it over. I thought, “Well, I’ll give it a try. I’ve never taught before.” I took it over while it was still uptown. The class was only a couple days a week. When we moved down to 23rd St., we had a whole building of our own. Then it began to prosper under the G.I. Bill, so we got far more students. My schedule went from a couple days a week to four or five days a week, for four hours, as I said — that’s when I was young and foolish!

GROTH: Before you actually started teaching did you have to go through a screening process with Burne or anything like that?

ROBINSON: No. I mean, I’d already lectured there. In fact, I’m sure I first met Burne when I took over Mort’s class. I guess I talked to him and he knew my background.

GROTH: So you did not have to run a gauntlet?

ROBINSON: No. What would that be?

GROTH: That would be being interrogated by Burne as to your suitability.

ROBINSON: I see. No. I don’t recall anything like that. Years later, I took an exam and was certified by the N.Y. State Board of Education.

BURNE HOGARTH

GROTH: Did you get to know Burne socially as well as professionally?

ROBINSON: Absolutely. We became very close friends — I think my closest after Mort and Bernie. When we moved down to 23rd St., Burne lived on the West End just around the corner from me. So after class at 10 o’clock, Burne would teach at night also. We would drive home together, have dinner together either at a restaurant or up at his place. His wife became good friends as well.

GROTH: Was he married to Connie at the time?

ROBINSON: Connie. Yes.

GROTH: You know, Burne was a very dominating figure. Was he so back then?

ROBINSON: In his dealings with other people and in class and lecturing he was. Our relationship wasn’t like that. No. We went to plays together. We went to dinner together. In fact, I had a place in the country, which he loved, and he and Connie bought one of the summer places on the same lake so we had more time together in the summer.

GROTH: Would that be in upstate New York?

ROBINSON: Not too far. Near Pauling.

GROTH: So you very much enjoyed Burne’s company?

ROBINSON: Oh, yes. It was always stimulating. I particularly loved to go to plays with him, which we did regularly and went to dinner afterwards, because we’d then get engrossed in talking about the drama or about that particular play and get off comics for a bit. There was enough discussion about comics, but that was enjoyable too. We lectured together quite often. A few times a year we would have big seminars. What we’d do was take a subject like composition or perspective or drapery or anatomy of the head, and we’d devote a couple of hours to it and the whole school would be invited. We would just jam that lecture hall. We would each pass the mike and the easel back and forth. I think it was less forth than back with Burne, but he would add his own dimension and historical perspective. Plus, he was a master at the chalk drawings, the demo drawings.

GROTH: I have one of those on my wall.

ROBINSON: They’re beautiful. So of course I learned from him, the tricks of how to do the demo chalk drawings.

GROTH: When you were joint lecturing, what was the subject of the lectures?

ROBINSON: As I said, we’d select a new subject each time, one that we thought the students weren’t sufficient in and would benefit from an intense session on the subject. So I remember some were drapery, which is important, and perspective; how to do street perspectives and parts of the anatomy — the hand or heads; composition. The basics, really, page layout, storytelling, etc.

GROTH: Did you admire Burne’s Tarzan work?

ROBINSON: Yes. I did. He did these very classical compositions. They were tighter than I would have liked, myself. In fact, I preferred a lot of [Hal] Foster’s Tarzan, but he did some remarkable things in Tarzan as well. As you know, he was lauded as a genius in France.

GROTH: Yep. He and Jerry Lewis.

ROBINSON: [Cracks up.] That’s right.

GROTH: I tended to think that he sometimes had a tendency to over-elaborate the rendering of his material.

ROBINSON: I guess I would agree. That was part of the difference between he and Foster. Foster was much lighter, freer, looser. Burne was more dramatic and academic and anatomical.

GROTH: Yes. And that would be a difference between your work and Burne’s as well. Yours was much looser.

ROBINSON: Yeah. I think so. My only criticism of Burne as a teacher, a lecturer, was that he was too strong. He would overpower the student. A lot of them felt they had to draw like him to gain his favor. I would argue about that, that he didn’t want to create little Hogarths.

GROTH: I sat in on at least one of Burne’s teaching lectures and I would describe his technique as “learn or die.” [Robinson laughs.] But it was invigorating.

ROBINSON: That was why it made up for the other things. He invigorated everyone. Those that followed it too closely didn’t get as much out of it because they were restricted by his knowledge and they couldn’t match what he was doing. There’s just one Hogarth.

Jet Scott

GROTH: In 1953, you started the science fiction strip Jet Scott?

GROTH: In 1953, you started the science fiction strip Jet Scott?

ROBINSON: About then, yeah.

GROTH: This was written by someone named Sheldon Stark?

ROBINSON: Right.

GROTH: And distributed by Herald Tribune Syndicate.

ROBINSON: Yes.

GROTH: Can you tell me about how that came about and what prompted you to become involved in that?

ROBINSON: I don’t think I did very much art other than Jet Scott during the couple years that I did it. It was very time-consuming, almost obsessive. In fact, that’s one of the reasons I finally didn’t continue.

I’m not sure who it was who knew me at Herald Tribune Syndicate. All I recall now, I got a call from the editor to come down to talk about a feature. I didn’t know Sheldon Stark. I’d never heard of him. The syndicate put us together. I met Sheldon there. He was from California, a screenwriter. I think a close relative of his was a well-known producer at the time.

Sheldon had not written any comics before, that I recall. This became a problem for me once we started the script. What the Tribune Syndicate did in those days was market the strip to daily as well as Sunday papers. They wound up with a list of some dailies only, some dailies with Sundays, and some Sundays-only if you can believe the headache that caused.

GROTH: So you had to do two stories simultaneously?

ROBINSON: Well, almost three. You had to write the dailies without the Sundays, picking up on Monday. Then you had to make the Sunday fit in the dailies then making sense with Monday. Then you had to make the continuity from Sunday to Sunday. It was ridiculous. Some syndicates at the time had Sunday-only continuities. I remember for the Daily News I think it was Gasoline Alley for one. It had the same characters but it had a different story line on Sundays from the dailies.

GROTH: Yeah.

ROBINSON: Well, they tried to do both, which was a real headache.

GROTH: That sounds insane.

ROBINSON: Yeah. That was insane, and Stark wasn’t the best at connecting the weeks. He had great ideas and premises to launch a story, but couldn’t tie it up and bring it to a conclusion. I had to rewrite and make sense out of it. It was just due to inexperience, I think, in the medium. I didn’t mind doing it, but time-wise it became a problem with deadlines. I was doing it alone, and adventure strips require a lot of work in the drawing alone. Most cartoonists who do daily and Sunday adventure have assistants. I did have a letterer — I certainly didn’t letter it — but that was it.

GROTH: And you had to do all of the extra work, for which you probably weren’t getting paid.

ROBINSON: No. I have to make it make sense if I put my name on it. There was research to do. It was an adventure strip. It was a burden. I really enjoyed doing it, and I think I did some fairly credible sequences. Also, I think it was the Tribune’s idea to market six-week stories — short stories and not long continuous episodes. They were good at this, I must say, in retrospect. They would do a new promotion for each sequence. They could do the follow-up marketing very quickly. We built up a good list for that time in the two years. We reached somewhere around 75-to-100 in that short time, of major papers. You know, you could have a list of 200 or 500 and not make as much as with 75 or 100 of major papers.

GROTH: That’s right, because they pay based on their circulation.

ROBINSON: Exactly. You could have a paper pay $15.00 a week and, for the same thing, a large paper’s rate could be $250.00 a week. Anyway, in two years we got a good list, with the Herald Tribune newspaper in New York as the flagship paper. My first contract was two years. It came to renewal and I had great reservations, because in two years I didn’t have a day off and the problems with the story. It was a tough decision. By that time it had a fairly good income. But I had given up all of my other accounts. I finally made a decision to drop it, and the syndicate didn’t want to continue it without me.

I also felt that we had reached a plateau of sales of the major papers. I really had a fear, strangely enough, of having it become too successful where I never could walk away from it, because there were other things I wanted to do. I wanted to do more of my own writing and drawing, and I wanted to do books, which I’d begun to get offers for. I wanted time for more photography and painting.

And the other factor: There were a couple of other science-fiction strips at that time. We were basically known as a science-fiction strip, although Jet Scott was a science investigator, but the science we used was just the advanced science based on current knowledge. It wasn’t futuristic. It wasn’t a Flash Gordon strip or a ... what was the other one?

GROTH: Buck Rogers?

ROBINSON: Buck Rogers, yes. There was a strip by Lee Elias, Beyond Mars, in the Daily News that folded after about a run of the same length, and there were other science-fiction strips that also folded. I figured the cycle of science-fiction strips was over.

GROTH: It almost sounds more like a science-fact strip.

ROBINSON: Yes, it was in a way. Jet Scott was a science investigator in the Office of Scientifact, an agency we made up.

GROTH: You may have been more prolific than you remember, because according to this checklist I have, in 1952, ’53, ’54 — the same time you were drawing Jet Scott — you also did a number of books for Stan Lee. You did Girl Confessions, Justice Comics, Love Romances ...

ROBINSON: During those same two years?

GROTH: Yeah.

ROBINSON: Oh, God.

GROTH: You’re actually more energetic than you thought.

ROBINSON: More stupid, anyway.

GROTH: Right.

ROBINSON: Apparently, I was conflicted about it: If I continued Jet Scott, I wouldn’t have time for anything else. I was really down. If I was doing all of that no wonder I felt that I had to cut down the load. As fate would have it, and I’ve written about this, as I recall, in my history, The Comics, about the science cycle. I don’t think it was more than six months after we stopped the strip that the Russians sent off the first rocket around the earth, Sputnik. Well, that was a momentous event. The Russians beat us into space! There was a whole new rush toward science fiction and new strips came out based on that. If we had not quit then, I might be doing Jet Scott today. Who knows? If we had continued, I’m sure we would have sold another 100 papers. You never know how fate will have it, but I’ve never regretted it.

(Continued)