NOTE: Giraud’s astonishingly varied and lengthy career resists a simple, succinct obituary. I hope that I have managed to tame it into a coherent narrative, and have not let too many foolish mistakes slip in due to time pressure. (I feel Dan Nadel’s breath on my neck even as I finish this introduction.)

NOTE: Giraud’s astonishingly varied and lengthy career resists a simple, succinct obituary. I hope that I have managed to tame it into a coherent narrative, and have not let too many foolish mistakes slip in due to time pressure. (I feel Dan Nadel’s breath on my neck even as I finish this introduction.)

I met Jean only once, to conduct the interview that appeared (gah!) 25 years ago in The Comics Journal, and he was as sweet, modest, and affable as every other person who ever met him has reported. I have said for years now — in fact, probably since 2000, when Charles Schulz left us, and there were four — that the three greatest living cartoonists are Robert Crumb, Jacques Tardi, and Jean Giraud. In the last 48 hours, that number has shrunk to two.

Salut, Jean!

—Kim Thompson

Jean Giraud, the French cartoonist best known under his pen name “Moebius,” died Saturday in a Paris hospital after a lengthy battle with cancer, at the age of 73.

Like his namesake single-surfaced geometric figure, Giraud enjoyed two distinct careers that could be considered opposite sides of a coin, or a continuation of one another: As “Gir,” he co-created, illustrated, and eventually wrote the Western series Lt. Blueberry for over four decades, while as “Moebius,” he drew and often wrote some of the most revolutionary and dazzling science fiction comics ever created — as well as providing costume and set designs for such visually groundbreaking movies as Alien, TRON, and The Fifth Element.

Either career would have placed him at the forefront of his chosen trade; braided together into one astonishing life, the two made him indisputably one of the greatest cartoonists of the second half of the 20th century.

Giraud was considered a national treasure in his native country, and his death has been one of the major news stories there over the weekend, as virtually every practicing cartoonist joined together in mourning the passage of a true legend.

1. APPRENTICE

Born Jean Alphone Gaston Giraud on May 8th, 1938 in the Parisian suburb of Nogent-sur-Marne, the precocious Giraud, who had fed his childhood imagination with a steady diet of Franco-Belgian comics as well as (translated) Italian and American comics and strips, broke into comics before he’d turned 18 — appropriately enough with a Western strip created for the magazine Far-West. He spent his late teens and early 20s as a typical struggling cartoonist on the periphery of the field, selling the occasional story or short series to a variety of lesser publishers and magazines. (During this time he also enjoyed a nine-month stay in Mexico, whose desertscapes would have a profound impact on him, and served his mandated time in the military.)

In 1961, Giraud apprenticed for the great Belgian cartoonist Joseph Gillain (a.k.a. Jijé), among other jobs inking an entire episode of Gillain’s long-running Western series “Jerry Spring” for Spirou magazine. In later years, Giraud would always credit Gillain as a huge influence on his career and style (and Gillain would tip his hat to his student by painting the cover to his first published album).

A fan of satirical comics, Giraud kept his career simmering at the time by contributing regularly to the fledgling adult comics monthly Hara-Kiri, for which he created a handful of short, satirical strips heavily influenced by the Harvey Kurtzman MAD in its initial comics iteration) particularly as illustrated by Will Elder). But his first big success was about to drastically focus Giraud’s attention, driving him away from this type of work (and from the “Moebius” pseudonym he’d adopted for it).

2. GUN FOR HIRE

In 1963, Giraud walked into the offices of Pilote, an upstart comics weekly that had been created a few years earlier to challenge the hegemony of the Belgian powerhouses Tintin and Spirou, and then found itself perched atop a rocket when one of its features, René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s “Astérix,” began taking off. Giraud was greeted by Jean-Michel Charlier, the managing editor (and writer of two of Pilote’s other major series), who was, as it happens, casting about for an illustrator for the new Western series he had conceived: “Lt. Blueberry.” (Giraud would later joke that Charlier had probably accepted the editorial position in part so he could cherry-pick the most promising new cartoonists as they walked in the door.) Giraud’s portfolio, including the Gillain collaboration, proved enough of a reference for the young artist and the first installment of the first Blueberry story, “Fort Navajo,” debuted in the October, 31st edition of Pilote as the cover feature.

Thus Giraud, or as he signed himself, “Gir,” became the co-creator of what would soon be one of the landmark series of Franco-Belgian comics. Despite a few interruptions due to creative or contractual problems over the years, “Blueberry” would remain a constant in Giraud’s career, ending only four decades and 28 albums later.

Thus Giraud, or as he signed himself, “Gir,” became the co-creator of what would soon be one of the landmark series of Franco-Belgian comics. Despite a few interruptions due to creative or contractual problems over the years, “Blueberry” would remain a constant in Giraud’s career, ending only four decades and 28 albums later.

As it turned out, the 1960s proved the perfect decade for an ambitious young French cartoonist to launch a Western strip. Previously a stodgy genre in which white-Stetsoned heroes bloodlessly shot revolvers out of the hands of grimacing villains, the film Western had begun to take on a darker, more violent and sexual edge beginning with Sergio Leone’s revisionist “Man With No Name” trilogy (Per un pugno di dollari, a.k.a. A Fistful of Dollars, 1964) to its full, bloody consecration with Sam Peckinpah’s groundbreaking The Wild Bunch at the end of the decade.

Combined with the 1968 liberalization of the previously strict rules governing Franco-Belgian kids’ comics that allowed them to slide into slightly more adult, or at least adolescent territory, Pilote editor-in-chief Goscinny’s willingness to push boundaries, and the general cultural ferment of the 1960s which had also penetrated the comics field (especially with Eric Losfeld’s groundbreaking releases of Jean-Claude Forest’s Barbarella and Guy Peellaert’s The Adventures of Jodelle in 1964 and 1966), the initially undistinguished “Blueberry” was allowed to morph into a relatively grubby, violent, even sexy series. (It didn’t hurt that Giraud had modeled Blueberry on the then-current icon of French cool, Jean-Paul Belmondo.)

Combined with the 1968 liberalization of the previously strict rules governing Franco-Belgian kids’ comics that allowed them to slide into slightly more adult, or at least adolescent territory, Pilote editor-in-chief Goscinny’s willingness to push boundaries, and the general cultural ferment of the 1960s which had also penetrated the comics field (especially with Eric Losfeld’s groundbreaking releases of Jean-Claude Forest’s Barbarella and Guy Peellaert’s The Adventures of Jodelle in 1964 and 1966), the initially undistinguished “Blueberry” was allowed to morph into a relatively grubby, violent, even sexy series. (It didn’t hurt that Giraud had modeled Blueberry on the then-current icon of French cool, Jean-Paul Belmondo.)

Nor did it hurt that Giraud turned out to be one of the greatest natural talents in comics history. The first decade’s worth of “Blueberry” books showed dramatic gradual improvement, as Giraud’s drawing (unfailingly precise even as it seemed ever more effortless) was matched by a growing knack for design (especially the sophisticated integration of word balloons into the pages) and sheer narrative verve. By the end of the decade, with ten albums under his belt, Giraud was the indisputable master of the realistic adventure comic strip, and “Blueberry” the peak of the form — particularly as Giraud fought for, and eventually gained control of, the coloring of his work.

Even though he had been typecast as a Western cartoonist literally from his first strip, Giraud remained loyally devoted to science fiction and, as he continued to spend the bulk of his time on “Blueberry” (80% by his own estimate, he would say later) began indulging this taste with a series of SF-oriented illustrations and book covers, as well as contributing to a column on the subject in the pages of Pilote along with fellow aficionados Philippe Druillet (the creator of Lone Sloane) and Jean-Pierre Dionnet. This interest culminated in the watershed short story “La Déviation,” a Moebius-style fantasia that ran in a 1973 issue of Pilote (albeit still under the “Gir” signature) and signaled a radical stylistic and narrative departure for Giraud — and, indeed, for French comics in general.

3. HUMANOID

As flexible and dynamic as Pilote had become under Goscinny’s admirably catholic (with a small “c”) editorship — inspired by MAD magazine and recent innovations in the French comics field, he had initiated a section of satirical “current events” strips in Pilote and was introducing some startlingly contemporary cartoonists into the magazine — the tension between the cartoonists’ desires and the remaining strictures of a mass-market magazine geared at most for adolescents became intolerable.

Three of Goscinny’s star cartoonists — Claire Bretécher, Nikita Mandryka, and Marcel Gotlib — had left the magazine in 1972 to start their own underground comix-inspired adult magazine, L’Écho des savanes, and it was only a year later that another group of Pilote cartoonists, in a famously acrimonious group meeting, confronted Goscinny about their grievances. Even though Giraud would continue to draw “Blueberry,” the family feeling Goscinny had tried so hard to foster was irrevocably shattered, and a year later an embittered Goscinny stepped down from the editorship of the magazine, which soon went monthly and slid into a long decline over the next decade until it was cancelled. (Goscinny died in 1977 at the age of 51.)

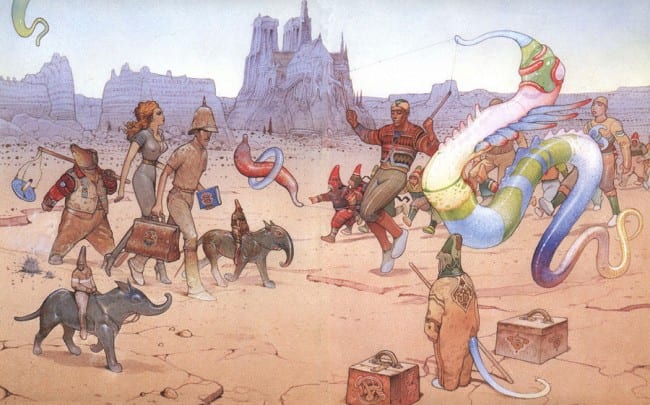

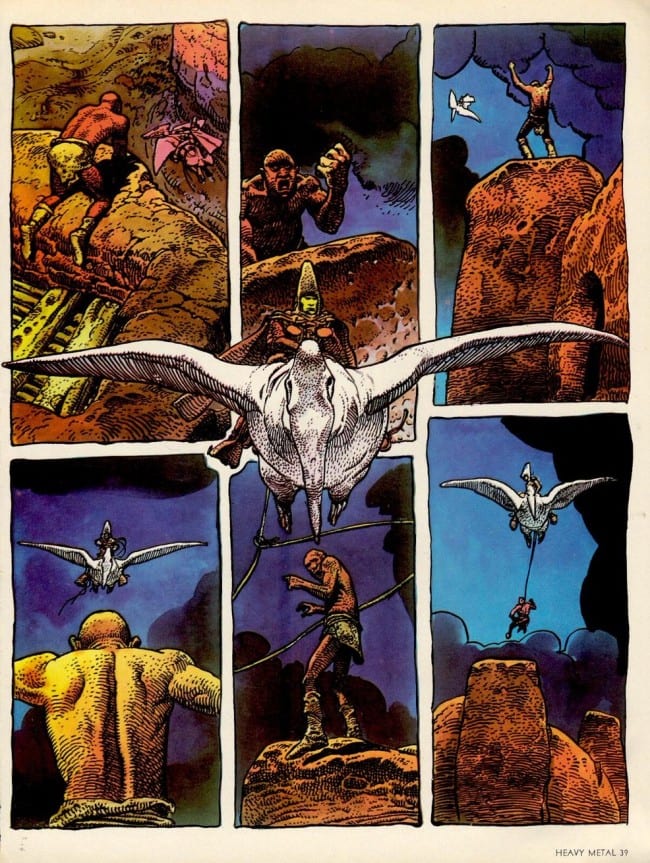

And so the “Moebius” signature made its reappearance in L’Écho (in the story “White Nightmare”), and soon Giraud joined his friends Druillet and Dionnet, as well as a fourth founder Bernard Farkas, to create the similarly-formatted adult science fiction comic Métal Hurlant (and along with it its publishing arm, Les Humanoïdes Associés). For the rest of the 1970s, Giraud would divert much of his focus from “Blueberry” (which was still running in Pilote regardless of the Goscinny dust-up — in part because the series’ substantial royalties funded Giraud’s far less profitable alternative work) to focus on an astonishing run of wildly inventive series and stories for Métal, including the stunningly-colored, wordless surrealistic fantasy series “Arzach” and the whimsically disjointed, Michael Moorcock-inspired “Garage Hermétique de Jerry Cornelius,” both of which premiered, to the delight and frequent bafflement of readers, in the first issue of Métal.

And so the “Moebius” signature made its reappearance in L’Écho (in the story “White Nightmare”), and soon Giraud joined his friends Druillet and Dionnet, as well as a fourth founder Bernard Farkas, to create the similarly-formatted adult science fiction comic Métal Hurlant (and along with it its publishing arm, Les Humanoïdes Associés). For the rest of the 1970s, Giraud would divert much of his focus from “Blueberry” (which was still running in Pilote regardless of the Goscinny dust-up — in part because the series’ substantial royalties funded Giraud’s far less profitable alternative work) to focus on an astonishing run of wildly inventive series and stories for Métal, including the stunningly-colored, wordless surrealistic fantasy series “Arzach” and the whimsically disjointed, Michael Moorcock-inspired “Garage Hermétique de Jerry Cornelius,” both of which premiered, to the delight and frequent bafflement of readers, in the first issue of Métal.

Around the same time, Giraud was (along with fellow designers Chris Foss and H.R. Giger) roped into a madly ambitious and ultimately doomed project to film Frank Herbert’s Dune. But Giraud’s widely-circulated drawings for the aborted project not only provided an entrée for Giraud into the film world (Ridley Scott would later hire the same trio for his Alien movie — incidentally based on a story by Dan O’Bannon, who had written the SF noir detective short story “The Long Tomorrow,” one of Moebius’s Métal -era classics), but introduced him to someone who would turn out to be his most frequent and prized collaborator next to Charlier: The Chilean-French filmmaker, cartoonist, and all-around provocateur who had been supposed to direct this epic, Alejandro Jodorowky.

Around the same time, Giraud was (along with fellow designers Chris Foss and H.R. Giger) roped into a madly ambitious and ultimately doomed project to film Frank Herbert’s Dune. But Giraud’s widely-circulated drawings for the aborted project not only provided an entrée for Giraud into the film world (Ridley Scott would later hire the same trio for his Alien movie — incidentally based on a story by Dan O’Bannon, who had written the SF noir detective short story “The Long Tomorrow,” one of Moebius’s Métal -era classics), but introduced him to someone who would turn out to be his most frequent and prized collaborator next to Charlier: The Chilean-French filmmaker, cartoonist, and all-around provocateur who had been supposed to direct this epic, Alejandro Jodorowky.

After they had collaborated on Les Yeux du Chat (published in 1978), Jodorowsky proposed to Moebius an ambitious story cycle: The Incal. Launched in 1980, the Incal saga would eventually run six volumes over the following seven years, making it the second longest of Moebius’s single works (behind “Blueberry”).

A cult filmmaker, Jodorowsky had seen his cinematic fortunes dim after the success of El Topo (he would release only one film between 1973’s The Holy Mountain and his 1989 semi-comeback Santa Sangre), but the Incal’s success allowed him to pivot to a successful and still ongoing career as the writer for a number of graphic album series, including several Incal spin-offs drawn by other hands. Giraud himself would re-team with Jodorowsky in the early 1990s for the cheerfully profane and sacrilegious three-volume La Folle du Sacré-coeur (The Madwoman of the Sacred Heart).

A cult filmmaker, Jodorowsky had seen his cinematic fortunes dim after the success of El Topo (he would release only one film between 1973’s The Holy Mountain and his 1989 semi-comeback Santa Sangre), but the Incal’s success allowed him to pivot to a successful and still ongoing career as the writer for a number of graphic album series, including several Incal spin-offs drawn by other hands. Giraud himself would re-team with Jodorowsky in the early 1990s for the cheerfully profane and sacrilegious three-volume La Folle du Sacré-coeur (The Madwoman of the Sacred Heart).

4. GLOBETROTTER

In 1984 Giraud moved to Los Angeles, in part to work within the film industry, and in part to oversee his work’s expansion into the American market. (Métal Hurlant had been spun off into the American Heavy Metal in 1977, where he immediately became the star artist along with Richard Corben). In particular, Marvel Comics’ Epic imprint had purchased most of Giraud’s work and released it in an expansive series of full-color albums over a period of five years from 1987 to 1991, including nine “Moebius” books focusing on his science fiction and a half-dozen more collecting all but the earliest, crudest “Blueberry” volumes.

In 1984 Giraud moved to Los Angeles, in part to work within the film industry, and in part to oversee his work’s expansion into the American market. (Métal Hurlant had been spun off into the American Heavy Metal in 1977, where he immediately became the star artist along with Richard Corben). In particular, Marvel Comics’ Epic imprint had purchased most of Giraud’s work and released it in an expansive series of full-color albums over a period of five years from 1987 to 1991, including nine “Moebius” books focusing on his science fiction and a half-dozen more collecting all but the earliest, crudest “Blueberry” volumes.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Giraud seemed to flit from project to project, including a collaboration with Stan Lee on a Silver Surfer graphic novel; a revival of the “Garage Hermétique” world in collaborations with his agent/translator Jean-Marc Lofficier and the artists Eric Shanower and Jerry Bingham; new installments of the “Jim Cutlass” series (a short-lived Moebius-inflected Western created a decade earlier with Charlier as a replacement for “Blueberry” during a spat with Dargaud, shelved as soon as the spat was resolved) now drawn by Christian Rossi; a portfolio with the Moebius-inspired Geof Darrow; two episodes of a Little Nemo album series drawn by Bruno Marchand (inspired by the story and graphic work Giraud had provided for a full-length, Japanese-produced animated Little Nemo feature film; and more.

But Giraud’s main post-Incal work was the “Edena” cycle, a series of books spun off from Sur l’Étoile, a story initially intended as a full-length comic promotion for Citroën that became an entire cycle of graphic novels. These ecologically-minded stories showed a less cluttered, more “clean-line” style, and showcased Giraud’s increasing interest in nutrition, meditation, and crystals.

But Giraud’s main post-Incal work was the “Edena” cycle, a series of books spun off from Sur l’Étoile, a story initially intended as a full-length comic promotion for Citroën that became an entire cycle of graphic novels. These ecologically-minded stories showed a less cluttered, more “clean-line” style, and showcased Giraud’s increasing interest in nutrition, meditation, and crystals.

5. LEGEND

After Charlier’s death in 1989 and subsequent release of “Arizona Love,” the final Charlier/Giraud “Blueberry” album, it seemed, particularly given the sheer profusion of Giraud’s other interests and the erratic release schedule of the series in the 1980s (Giraud was well past needing the money from the series), that “Blueberry” might be dead, at least so far as Giraud was concerned. (The last few titles had taken on an undeniable air of imminent closure as well: “The Last Card” and “The End of the Trail.”) But Giraud (who had occasionally stepped in and ghosted sequences of the Charlier-era “Blueberry” when Charlier would fall behind deadline, and in fact had completed the last album after Charlier’s death) quickly returned to the series as the writer, working on a separate trilogy of “Marshall Blueberry” prequel albums with first the veteran artist William Vance (XIII) and then Michel Rouge. (The endlessly exploitable Blueberry was also featured in a still-ongoing “Jeunesse de Blueberry” spinoff in which Giraud was not involved. An intriguing-sounding “Blueberry 1900” series proposal featuring an older Blueberry which Giraud had developed for François Boucq to draw was shot down by Charlier’s heirs due to its focus on drug use and shamanism — elements that turned up again in Jan Kounen’s widely panned 2004 film Blueberry, l’expérience secrète which, perhaps not coincidentally, Giraud, although not part of the official creative team, supported and provided a cameo for).

After Charlier’s death in 1989 and subsequent release of “Arizona Love,” the final Charlier/Giraud “Blueberry” album, it seemed, particularly given the sheer profusion of Giraud’s other interests and the erratic release schedule of the series in the 1980s (Giraud was well past needing the money from the series), that “Blueberry” might be dead, at least so far as Giraud was concerned. (The last few titles had taken on an undeniable air of imminent closure as well: “The Last Card” and “The End of the Trail.”) But Giraud (who had occasionally stepped in and ghosted sequences of the Charlier-era “Blueberry” when Charlier would fall behind deadline, and in fact had completed the last album after Charlier’s death) quickly returned to the series as the writer, working on a separate trilogy of “Marshall Blueberry” prequel albums with first the veteran artist William Vance (XIII) and then Michel Rouge. (The endlessly exploitable Blueberry was also featured in a still-ongoing “Jeunesse de Blueberry” spinoff in which Giraud was not involved. An intriguing-sounding “Blueberry 1900” series proposal featuring an older Blueberry which Giraud had developed for François Boucq to draw was shot down by Charlier’s heirs due to its focus on drug use and shamanism — elements that turned up again in Jan Kounen’s widely panned 2004 film Blueberry, l’expérience secrète which, perhaps not coincidentally, Giraud, although not part of the official creative team, supported and provided a cameo for).

But this turned out to be just a prelude to the five-volume “Mister Blueberry” storyline, which Giraud wrote and drew between 1995 and 2005 and which, aside from wrapping up his “Edena” and “Madwoman” cycles, turned out to be his major work in this period — a late-career return to the 1960s-era dominance of “Blueberry” on his drawing table.

Injecting Blueberry into the legendary “O.K. Corral” storyline already popularized by countless movies and books, Giraud delivered a surprisingly “classic” novel-length story, although he puckishly wrote the entire first volume with Blueberry sidelined from the action throughout, finally getting up from the poker table at which he had spent the entire album only to be shot down and (maybe) killed on the last page. It was a fitting last hurrah for one of the all-time great comics characters.

6. FULL CIRCLE

For what would turn out to be the last decade of his life, Giraud would, with the “Mister Blueberry” cycle behind him, mostly devote himself to Inside Moebius, a self-published (under the “Stardom” imprint run by his wife) six-volume series of loosely drawn, meditative diary-type albums in which Giraud himself interacted with his characters, his younger self, and the occasional real-world person such as Osama Bin Laden, set in endless desertscapes that were probably not far from the Mexican vistas he’d enjoyed a half century earlier. (Stardom had also brought forth, since 1996, a flood of art books and portfolios devoted to the artist.)

Although he also wrote a few books for other cartoonists (Icare a.k.a Icarus for the Japanese cartoonist Jiro Taniguchi and Altor for Marc Bati), and (somewhat inexplicably) drew a fill-in episode of the mainstream thriller series XIII, it seemed for a while that Giraud had created his last story — until the 2008 release of Major Fatal: Le chasseur déprime (again released by Stardom), a spectacular, black-and-white return to the playful, elaborate mythology of the “Garage Hermétique” world from the Métal Hurlant days. The signatures on the pages, which ran from 2005 to 2008 (with a handful of pages as far back as 1998), hinted at a long, meandering development, but the visually and narratively eclectic results dovetailed nicely with the “Garage” concept — and readers were grateful for the first real new “pure” Moebius narrative album since the somewhat disappointing end of the “Edena” cycle seven years earlier.

Even more striking, this was followed, in 2010, by Arzak: L’Arpenteur, a freewheeling, full-color science fiction adventure — his most narratively straightforward work to appear uder the “Moebius” credit in years — that brought back his iconic Métal Hurlant character and dropped him into an elaborate science-fiction potboiler. Arzak was intended to run for three annual volumes, and the first one ended on a cliffhanger, but 2011 came and went without the second installment (for what are now sadly obvious reasons); how far Giraud might have gotten on it before being sidetracked by his illness is not known yet. And it seems fitting that his obituary would end with, in essence, “to be continued…”