From The Comics Journal #134 (February 1990)

It’s accurate enough to refer to Jack Kirby as an American original, but it’s hard to know where to place the emphasis — on American or original. He’s certainly both, in spades. Renowned as one of the handful of true artistic giants in the history of comic books, it’s difficult to come up with encomiums that have not become commonplace. Although I had known Jack for some time and spoken to him not infrequently prior to conducting this “formal” interview, it was not until I read over the transcript that I understood just how thoroughly Jack is a child of his time and place. Growing up on the Lower East Side shaped his life and his work which, combined with a robust imagination and seemingly inexhaustible energy, substantially shaped the trajectory of the American commercial comic book. A dubious contribution to the American comic book, you may think, until you realized that it wasn’t Kirby’s fault that hacks and no talents, aided and abetted by opportunistic publishers, have been ripping off his work and plagiarizing him wholesale for decades. Though the refined eyes of the aesthete may consider Kirby’s work crude, ornery, and anti-intellectual, the fact remains that he combined the virtues and limitations of his class with a stubborn genius to produce a body of comics work that has remained consistently true to its source and is unparalleled both in quantity and quality. This interview was conducted in three different sessions over the summer of 1989 at the Kirby’s comfortable home in Thousand Oaks, a suburb of Los Angeles. Jack’s wife, Roz, sat in on the interviews and helped recall with precision key points in Jack’s career. My thanks to them both, specifically for helping assemble artwork illustrating this interview, and more generally for their friendship over the last half dozen years.

All images written and drawn by Kirby unless otherwise noted.

GROWING UP ON THE EAST SIDE

JACK KIRBY: I don’t know where your father comes from, but where I came from, everybody was an immigrant. My people were from Europe. My family came from Austria, both my mother and my father. We lived on New York’s Lower East Side. The value of money was different then. We paid $12 rent a month, and a nickel was worth maybe the equivalent of a dollar today. It was very hard for a young man to get a nickel from his mother, but somehow you managed. When I visited New York, somebody thought it would give me a big thrill if he took me down there where I grew up, and I’d be thrilled by the sight of my humble origins, and I hated the place. I wanted to get out of there! [Laughter.]

GARY GROTH: Now this is the Lower East Side. Exactly what street?

KIRBY: It was on Suffolk Street. It was right next to Norfolk Street, and I went to school at P.S. 20.

GROTH: Why did you hate the place?

KIRBY: I hated the place because I... Well, it was the atmosphere itself. It was the way people behaved. I got sick of chasing people all over rooftops and having them chase me over rooftops. I knew that there was something better, and instinct told me that it was uptown, and I’d walk every day from my block to 42nd Street where the Daily News was, where I could be near the Journal, the Hearst newspapers. I’d run errands for the reporters. My boss was playing golf [in the office], and he was shooting golf balls through an upturned telephone book, see? That’s the kind of job I wanted! [Laughter.]

GROTH: Was this a poor neighborhood?

KIRBY: Where I came from, Suffolk Street? It still is, and Norfolk Street next to it still is. The whole area is extremely poor.

GROTH: What did your father do?

KIRBY: My father worked in a factory like everybody else’s father.

GROTH: And your parents were immigrants?

KIRBY: My parents were immigrants. And the place for all immigrants was the factories. They were the source of cheap labor. The immigrants had to make a living. They had to support their families, and they did it on very little, and so we had very little... You know, we couldn’t wear the best of clothes. I always wore turtleneck sweaters and knickers when I could get them. There were two of us, my brother and I. My brother is gone. He passed away, so I’m the only one left in the family. He was a younger brother. He was five years my junior. He was bigger. He was about 6’ 1”, very broad kid, and when I came out of school, I’d be jumped by all these guys, and he’d see my feet sticking out of this pile and dive in. And he’d pull me out from under this pile, and he’d whale in to them.

GROTH: Now, when you say you were jumped and your feet were sticking out of a pile of bodies, it sounds amusing now, but I assume it wasn’t amusing then.

KIRBY: It’s not even amusing now that I think about it. You know, the punches were real, and the anger was real, and we’d chase each other up and down fire escapes, over rooftops, and we’d climb across clotheslines, and there were real injuries.

GROTH: This was a tough neighborhood.

KIRBY: This was the toughest!

GROTH: Can you explain what you mean by that? Were there gangs?

KIRBY: Yes, there were gangs all over the place. Some of my friends became gangsters. You became a gangster depending upon how fast you wanted a suit. Gangsters weren’t the stereotypes you see in the movies. I knew the real ones, and the real ones were out for big money. The average politician was crooked. That was my ambition, to be a crooked politician. I’d see them in these restaurants, and they’d all hold these conferences. I’d see politicians who were supposed to be on opposite sides of issues all together at one table.

GROTH: Did this disillusion you about morality or politics in America?

KIRBY: If America gave anybody anything it is ambition. Bad things would come out of it because some guys are in a hurry, but that doesn’t mean they’re evil or anything, it just means they fall into bad grace somehow. It was hard to find work. A friend of mine was going to go out to get a job because his mother told him to get a job, so he said, I’ll go out and draw pictures and they’ll pay me for them. And his mother said, “No son of mine will become an artist. You’ll sit around with berets in Greenwich Village and talk to loose women.” Of course, mothers were very conventional, everything was very conventional. You had to have approval.

GROTH: There were very strict social conventions.

KIRBY: Very strict social conventions, and you adhered to it, and I think it gave you a lot of character. When a man said something, he meant it. He wasn’t kidding around. There were no jokes involved. Nobody was in the mood to joke unless you hit a guy with a baseball bat.

GROTH: Can you describe the social context a little more? The kid gangs that were running around: did they have their own turf? Did they run in real gangs?

KIRBY: They ran in gangs because they lived in certain places. Everybody who lived on Suffolk Street would be the Suffolk Street Gang. Everybody who lived on Norfolk Street would be the Norfolk Street Gang.

GROTH: Were there ethnic divisions?

KIRBY: Well, there were ethnic divisions, yes. Yes. Italians were predominantly Catholic. Some gangs were Irish, some gangs were black.

GROTH: Why was there such violence?

KIRBY: There was violence because first of all, there were ethnic differences and names. If you were small, they called you a runt, and you had to do something about that even if there were five other guys. There were a lot of ethnic slurs, there had to be, and I think in that respect that through the fighting, through the adversity, we began to know each other. I had never seen an Irishman. I’d never seen an Italian. My family had never seen an Italian. My family came from Central Europe, see, and they saw Germans and Austrians. You had to grow up sometime. The fellows who grew early, they were in jeopardy. They became the cops and the crooks, and the crooks became the gangsters. The crooks became the Al Capones.

GROTH: Were crooked politicians and gangsters looked on with disfavor?

KIRBY: They were looked on as acceptable, but with fear. Gangsters —

GROTH: Why were they — ?

KIRBY: — it wasn’t a matter of morals. It was what they wanted, how fast they wanted it. Now Capone ran Chicago. He ran the politicians. He ran the entire city. Yet his mother would come out and slap him around for not going to church on Sunday.

GROTH: Were they actually looked up to?

KIRBY: Yes, they were looked up to and feared. I think you can be looked up to out of fear just as much as you in look up to a man because of his ability or his promise. Adolf Hitler. I wouldn’t call Adolf Hitler a corporal, OK? Adolf Hitler was looked up to. He was revered almost like a God because he was feared. Adolf Hitler took all of Europe, and my generation had to confront Adolf Hitler.

GROTH: Did you yourself get in a lot of fights when you were a kid?

KIRBY: Yes. They were unavoidable.

ROZ KIRBY: And your brother got into a lot of fights.

KIRBY: Yes. As I said. my brother was a big kid.

GROTH: A tough kid?

KIRBY: He was as tough as anybody else, but he was young. He was five years younger than myself. My mother wanted my brother to wear nice clothes and be a big style kid. Well, can you imagine a big style kid with a lace collar and velvet pants and long, curly hair — blonde hair that came down to his shoulders? I’d get into fights because of my brother, and I got into fights because of his velvet pants and his lace collar, and my brother being a younger boy did the best he could, but I had to whale into these guys. I had to really whale into ’em, and I did. And it was a common, everyday occurrence. Fighting became second nature. I began to like it. And I love wrestling. When I went into the Army. I took judo. Out of a class of 27, just me and another fellow graduated. There was nothing wrong with me. I loved it.

GROTH: Now these fights in your neighborhood — these were serious, knock-down, drag-out fights.

KIRBY: Oh yes, they were. Not only that, but they were climb-out fights. There was a monument store. There was a store that built funeral monuments, and we used to run over those monuments. We used to hop from monument to monument chasing each other. For all I know, the may still be on Suffolk Street.

GROTH: Now, what do you mean by a “climb-out fight”?

KIRBY: A climb-out fight is where you climb a building. You climb fire escapes. You climb to the top of the building. You fight on the roof, and you fight all the way down again. You fight down the wooden stairs, see? And, of course, I didn’t win all of them. You fought fair. If the other guy wants to fight and you knocked him out, you did your best for him. You didn’t want to hurt him any more. There was one time they knocked me out and laid me in front of my mother’s door. And in order for my mother not to be shocked they readjusted my clothes and they saw that nothing was rumpled and I looked very comfortable next to the apartment door, so when my mother would open the door it wouldn’t be that much of a shock.

GROTH: Were you actually knocked unconscious?

KIRBY: Well, yes.

GROTH: Were you ever seriously injured? Broken bones, or...

KIRBY: No, I don’t think so. I was pretty good, to be frank with you, but against five guys…you know, it didn’t really faze me.

ROZ KIRBY: You were like Captain America.

KIRBY: Yes. Captain America would try to fight 10 guys. 1 said, How do you fight 10 guys? The fights in Captain America were very serious. If you looked them over. they’re real fights. I’d say, “What happens to this guy while Cap fights the other four?” And I would figure it out like a ballet. It would really be a ballet.

GROTH: Do you feel that your immersion in this violent world as a kid shaped these themes in your drawing and moved you in that direction?

KIRBY: Well, it helped me live. It helped me stay alive.

GROTH: I mean, do you think it affected the way you drew and the way you...

KIRBY: Oh, yes. You can judge it for yourself. You can see my early books on Captain America. I had to draw the things I knew. In one fight scene, I recognized my uncle. I’d subconsciously drawn my uncle, and 1 didn’t know it until I took the page home. So I was drawing reality, and if you look through all my drawings. you’ll see reality. When I began to grow older, I grew less... You don’t really grow less belligerent.

GROTH: [Laughing.] Right.

KIRBY: It stays inside you, somehow, and it always has its uses.

GROTH: What kind of recreational activities did you engage in as a kid? I mean, did you play stickball, or…?

KIRBY: Yes, I played everything. I played stickball. I played baseball. 1 played left end on my high school team.

GROTH: What was your relationship with your parents like?

KIRBY: My parents loved me. My father used to carry me around on my shoulders. I know my father loved me. All families love their children, and we were good boys.

GROTH: Did you enjoy school? Were you a good student?

KIRBY: I was a good student in the subjects that I wanted to be good in. The curriculum in my section was excellent. I have a good sense of history.

GROTH; Now, can you tell me what your family life was like? Were you close?

KIRBY: My family life was close. They were a wonderful family.

GROTH: I understand that as a kid you were something of a bookworm.

KIRBY: Yes.

GROTH: You had to sort of hide that fact from the other neighborhood kids. It wasn’t considered—

KIRBY: I did.

GROTH: How did you come to be interested in reading in such a tough neighborhood?

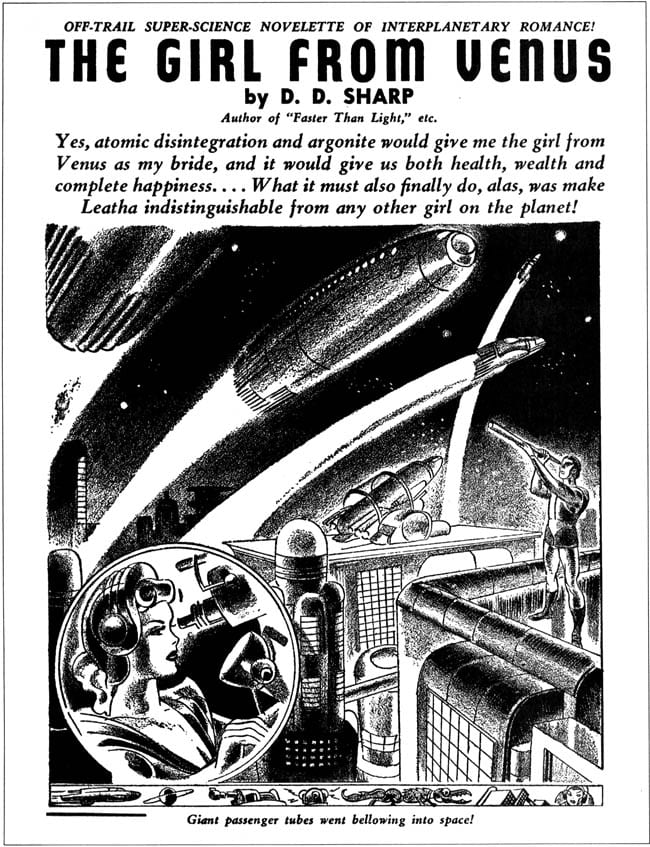

KIRBY: I came out of school one day, and there was this pulp magazine. It was a rainy day, and it was floating toward the sewer in the gutter. So I pick up this pulp magazine, and it’s Wonder Stories, and it’s got a rocket-ship on the cover, and I’d never seen a rocket-ship. I said, “What the heck is this?” I took it home and hid it under the pillow so nobody should know I was reading it. And of course, if the fellows caught me reading it or doing anything academic outside of school...

GROTH: Now, you read pulps. Did you also read newspaper strips?

KIRBY: Yes I did. I loved the newspaper strips. I loved Bamey Google . I think that’s what brought me into journalism. The comics are so large and colorful. The pages are extremely large, and I used to love that. And Prince Valiant, of course, it was astonishing to see this beautiful illustration in the newspaper, and it was so different from the ordinary comic.

GROTH: Let’s talk about how you learned to draw, I understand that at age 11, you began getting how-to-draw books at a local library and started —

KIRBY: Yes I did. In fact, I was drawing for a small syndicate. I was drawing editorial cartoons for the syndicate, and I drew a thing called “Your Health Comes First.” I was called in once for drawing an editorial cartoon when Chamberlain made that pact with Hitler. “Where does a young squirt like you,” he says, “get the nerve to do an editorial cartoon on Chamberlain and Hitler?” And I told him I know a gangster when I see one, see? Hitler was gobbling up all of Europe.

GROTH; Now what year would that have been? Would that have been around ’38?

KIRBY: Even earlier. That was around ’36. I was drawing any kind of comic strip art.

GROTH: What actually started you drawing? What gave you the idea you could draw?

KIRBY: I wanted to. I felt that I could. I’d been drawing all along because I felt anybody could do that. All human beings have the capability of doing what they want, what they’re attracted to.

GROTH: I think at the age of 14 you enrolled at the Pratt Institute.

KIRBY: Yes, I did.

GROTH: Can you tell me how you went about doing that? You were a kid in a tough neighborhood enrolling in the Pratt Institute. That’s got to be pretty unusual.

KIRBY: I went to the Pratt Institute, but I didn’t go there for long. I didn’t like places with rules.

GROTH: How long did you go to Pratt?

KIRBY: I went to Pratt a week. [Laughter.] I wasn’t the kind of student that Pratt was looking for. They wanted patient people who would work on something forever. I didn’t want to work on any project forever. I intended to get things done. I did the best drawing I could, and it was very adequate — it had viability, it had flexibility. The people in the art class kind of sympathized with me, and yet they couldn’t abandon their own outlook toward art.

GROTH: Would you say the Pratt Institute represented a fine art outlook?

KIRBY: Yes. It was a fine art outlook, it was a formal outlook, and it was a respected outlook. I respected it too. I had very high respect for the Pratt Institute, but I thought that I had done my best, and that was not their version of the best.

GROTH: So, after Pratt you taught yourself how to draw.

KIRBY: I taught myself how to draw, and I soon found out it was what I really wanted to do. I didn’t think I was going to create any great masterpieces like Rembrandt or Gauguin. I thought comics was a common form of art and strictly American in my estimation because America was the home of the common man, and show me the common man that can’t do a comic. So comics is an American form of art that anyone can do with a pencil and paper.

GROTH: It’s a democratic art.

KIRBY; It’s a democratic art. It’s not a formal art, I feel a fine artist is never through with his work because it’s never perfect to him.

GROTH: Don’t you think you achieved a sort of perfection in your own work?

KIRBY: Yes, I did. I achieved perfection, my type of perfection — visual storytelling. Storytelling was my style. I was an artist, but not a self-proclaimed great artist, just a common man who was working in a form of art which is now universal. I get letters from people of my own status.

GROTH: How did you teach yourself how to draw? Did you use books?

KIRBY: I used any method I could, really.

GROTH: Did you go outside and sketch from life? I’m trying to find out how you actually learned to draw, how you learned anatomy.

KIRBY: My anatomy was self-taught. I feel everybody has that ability. I drew instinctively. Mine was an instinctive style.

GROTH: Did you ever in your life think of taking any formal art training?

KIRBY: No. I tell young people that it’s advantageous to study art...

GROTH: Did you learn anatomy, where muscles are, and how they connect, and so on?

KIRBY: I searched it out, and I made my own muscles and I made my figures as powerful as Icould.

GROTH: How did you learn perspective?

KIRBY: You learn perspective... well, if you’re brought up in the city, if it doesn’t look right you’ll know it. But, if you grow up in a city and see the city, you’ll get a city as it really is with all the detail that you remember. If you’re drawing a Western town, you can duplicate that Western town from instinct alone. Some artists may take it from other illustrations or duplicate what you’ve drawn, but it will never have that gut reality that’s instinctive in the artist.

GROTH: What artists did you admire in your teen years?

KIRBY: I admired them all. I admired anybody who could make a buck with his drawing. [Laughter.]

GROTH: You must have had an eye for quality work.

KIRBY: I like quality work. Comics like Prince Valiant. I loved Milton Caniff and his work. Everybody did. If a man was good he was universally liked.

GROTH: Were you a very independent personality as a teenager?

KIRBY: Yes, I was.

GROTH: Where do you think you got that? Was that from your father?

KIRBY: No, just growing up on the Lower East Side.

GROTH: Did you see a lot of movies when you were a kid?

KIRBY: Yes. I was a movie person. I think it was one of the reasons I drew comics. They galvanized me. When Superman came out it galvanized the entire industry. It’s just part of the American scene. Superman is going to live forever. They’ll be reading Superman in the next century when you and I are gone. I felt in that respect I was doing the same thing. I wanted to be known. I wasn’t going to sell a comic that was going to die quickly.

GROTH: I understand you got a job with a small newspaper syndicate when you were 18.

KIRBY: Newspaper Features.

GROTH: What were you doing for them?

KIRBY: I was doing editorials. Like I said I did “Your Health Comes First”. I did another daily comic. On each comic strip I put a different name: I was Jack Curtis, Jack Cortez... I didn’t want to be in any particular environment, I wanted to be an all-around American. I kept Kirby. My mother gave me hell. My father gave me hell. My family disowned me.

GROTH: You actually changed your name to Kirby?

KIRBY: When I began doing the strips.

GROTH: Why did you change your name exactly?

KIRBY: I wanted to be an American. My name is Kurtzberg.

GROTH: Why didn’t you think Kurtzberg was an acceptable American name?

KIRBY: I felt if you wanted to have a great name it would be Farnesworth, right? Or Stillweather. I felt Jack Kirby was close to my real name.

GROTH: You’re Jewish. Was there anti-Semitism back then?

KIRBY: Yes. A lot of it. They were confrontational days when people of different backgrounds had to live together. And it hasn’t changed. There’s anti-Semitism today.

GROTH: Were you an Orthodox Jew?

KIRBY: My father was Conservative. We were never Orthodox, but we were Conservative. I went to Hebrew school. It was above a livery stable, the Hebrew school.

Until the day I die I’ll never forget that wonderful table we used to sit at. Hebrew school was a rough place. An airplane flew over one day and I ran over to the window and everyone was pushing and shoving each other, and some guy really shoved me out of the way — I knocked him clean out.

GROTH: How old were you?

KIRBY: I was about 12. Because I wasn’t bar mitzvahed yet. They had to pick him up. But, I was so eager. That was such an innovation to hear the sound of the motor of an airplane flying overhead. I just had to get there in front. I was attracted by everything that seemed to be new and advanced. I saw the Time Machine.

GROTH: Did you see Chaplin’s films?

KIRBY: Yes. I saw the Chaplin comedies, Buster Keaton. I saw the Marx brothers on a stage when they weren’t even in the movies.

GROTH: Was this on vaudeville?

KIRBY: This would be vaudeville. I’d go to the Academy of Music on 14th Street in New York. It might still be there for all I know. The Marx brothers came on stage and they did their act. I saw them in the movies. I loved the Marx brothers. I wanted to go to California and my mother said, “No, you can’t go to California.” Of course standards were different in those days — the mother was unassailable.

(continued)