For the first installment of this roundtable, go here, and for the second installment, go here.

EIGHT: KIRBY AS VISUAL ARTIST

DOUG HARVEY:

OK, I'm going to just spew out a few things as they come to mind. First, here's my initial response to Jeet's first email probe, before I got Hatfield's book:

I consider Kirby a visual artist, and a modern artist, by the same token and on the same playing field as any visual artist or modern artist, from Picasso or Duchamp to Jessica Stockholder or Banksy. And I rank Kirby very highly. I don’t see any need to make apologies or rationalizations for narrative or commercial parameters – Shakespeare and Hiroshige were commercial artists. It’s important to avoid self-ghettoizing the comics medium. Do we need to strain out the narrative intent inherent to virtually any pictorial artwork in order to assess its visual impact? Would we propose that for Picasso’s Guernica or Duchamp’s Large Glass? Personally I consider even the most abstract and conceptual artworks to be engaging the viewer in a narrative of some kind – often a more convoluted, context-dependent and reference-heavy one than that dictated by more patently illustrational figure paintings. For me, Kirby’s work holds its own on the strength of its visual impact, which necessarily includes his mastery of pictographic symbolism and graphic narrative composition. There’s no stronger argument than the work itself, and I’m astounded that anyone would need to read any book other than The Golden Helmet to recognize the genius of Carl Barks! Critics.

SARAH BOXER:

I’ve been watching the Kirby lovefest from the sidelines -- not with envy, but with a kind of fascination. Why I can’t I dive in? Why does my son want to? (I see a superhero comics fan in the making and I am horrified but interested too.) There must be a reason. Hatfield’s chapter “How Kirby Changed the Superhero” speaks to the point. And it also seems to explain my physical revulsion for almost all of the Kirby superheroes except, perhaps, the Silver Surfer, a giant phallus on a surfboard.

I like my superheroes smooth. Many of Kirby’s superheroes (and some of his anti-heroes) are encrusted, scaly, ripply. This encrustation strikes me as related to Christian iconography, which I also know nothing about. (See the attached photo of a work by Arthur Lopez at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, titled El Savador del Mundo.) Every layer is meaningful, not merely ornamental. And the layers seem designed to keep people like me out, people who don’t understand what the encrustation is all about. It is literally repulsive.

In his superhero chapter, Hatfield defines the difference between Kirby’s Marvel characters and the pre-Kirby DC superheroes like Batman (who would be my favorite superhero, if I were forced to pick one, which I am almost daily, by my son). The DC superheroes are smooth, streamlined, modernists in tightfitting pajama costumes. They are not so much clothed as depicted “though a haze of color,” Hatfield writes. The costumes, Hatfield continues, quoting Michael Chabon, are meant to show off “the naked human form, unfettered, perfect, and free.” P. 112

If the clothing has any job other than labeling the superhero, it is an ironic job. Hatfield calls the clothing of DC's superheroes “inherently ironic,” paraphrasing Terry Castle’s Masquerade & Civilization: “the superhero’s disguise … enabled its hero to invert his usual identity.” P. 113 I like that. Ironic clothing.

The Marvel heroes are not ironic. They are dead earnest, in constant deadly battle with Pure Evil. Cap battles the Nazis, not funny anti-heroes like The Joker. Hatfield writes, “the Marvel style was vigorous, even brutal… Marvel favored energy over smoothness.” P. 119 (By the way, this energy, is something I do admire about Kirby’s drawing. I also like that Kirby krackle -- the depiction of energy itself. And I like some of Kirby’s heirs like Gary Panter, who aren’t quite so earnest.)

The most interesting point (at least to me) in Hatfield’s book is that the Marvel superheroes are not only physically layered but semantically layered. They have layers of personal history & mythology, which they carry with them over time. They are encrusted with their own history.

As Hatfield writes, “the Marvel characters remembered -- and so did their readers.” And this historical encrustation, which the Marvel-type superhero carries with him, makes for a certain kind of fan.The Marvel readers are “addicted, soap-opera like, to continuing storylines and unresolved problems.” Captain America is a superhero soap opera. This is why I can’t jump into the discussion. This is why I don’t want to. Those super-encrusted layers of narrative clothing are super-nauseating and super-repulsive.

By contrast, the DC characters (as Umberto Eco has noted) are “blessed” with forgetfulness. They exist in what Neil Gaiman has called “a state of grace.” Each new story is a fresh starting point, naked and free. The characters have personality but they are, narratively, blank slates. As with a comic strip like Peanuts, anyone can dive in. Even me.

Linus is my idea of a great super-hero.

JONATHAN LETHEM:

Sarah, Doug: Two brilliants posts that slam against each other like a Superman-Thing slugfest.

I think I intuitively agree with Doug Harvey's context-demolishing blanket avowal of Kirby's pure value as an artist even more than I agree with anything I might have said myself earlier in this round-table. He's seeing the future: the job of posterity, pretentious term that it is, is precisely to dissolve the circumstantial brackets surrounding the site and occasion of the work's production and the mortal, humble, and often humiliating or awkward facts of the artist's person, and to begin to create a new context of its inevitable imperishable greatness, a contextual feeling suitable to the feeling it arouses in the viewer. Of course nobody but a fool ever wrote for money, everyone rushed their work to the marketplace and left it scarred with evidence of all sorts of local grudges, compromises, rivalries, and marketplace dynamics, including the marketplace of fashions or fads, (i.e. ancient astronauts) or meaninglessly eccentric personal references (i.e. Don Rickles), and while one job of scholarship is to nail down an accurate account of the context of the work's arising, an apparently totally conflictual purpose (or, at least, result) of the scholars rushing in to begin their work is that they are collaborating at building the platform for posterity to do its celebratory enshrinement. Hence some of the strange tensions inherent in a book like Hatfield's. His job, whether he knows it or not (I think he knows it) is to simultaneously speak for the Fiore side of things (Kirby is "like" Steve Ditko, Stan Lee, Gil Kane, etc. in that he consciously worked in tandem with and in reaction to a specific cultural operation, one subject to the restrictions and opportunities and self-definitions typical of that locality) and the Harvey side (Kirby is "like" William Blake and Picasso and Shakespeare in that you need to just forget all of the local context and say "look at what this fucking human did and how its inherent power and strangeness demands attention and needs no excuse or apology whatsoever" -- Behold!, in other words.)

As for Sarah, I'm going to go all baroque on you now and analogize your resistance to the Marvel thematics as being the result of a collision of dynamic models of the human psyche, one I'm supposing grates on your classical Freudianism --for the beautiful catastrophic difficulty with Marvel is that the heroes are subject simultaneously at all times to the pressures of living in an intimate Freudian universe, dominated by "the family romance" (Lee's side of things) and a Jungian one, where individual self-developmental fates are overwhelmed by the apprehension of vast archetypes of power moving through all human history (Kirby's side). "Overdetermined" might be the word. This muddle produces the encrustations which dismay you. Kirby, it seems to me, manifests the tension in his drawings themselves during his "classical period" (i.e. the core of the Fantastic Four run), by bringing romance-comic tenderness to the stances and facial expressions while burdening these same figures with the persistent onrush of his psychedelic techno-gnosticism.

(The reason Steve Ditko had to leave Marvel was that he subscribed to neither the Freudian nor the Jungian views -- his resistance to seeing the Green Goblin as some kind of familiar and shocking -- Lacanian? -- "other" for Spiderman being the defining crisis.) Ditko believes he is Ayn Randian. In my view he is Gurdjieffian.

The DC heroes are not so much even Freudian as they are a super-distilled and popularized Freudianism, akin to Dianetics. Each has one "origin-trauma" to solve, like an Engram: Batman's parent's mugged in that alleyway, Superman's planet exploding. Superman is what Dianetics would call a "Clear" -- his trauma is all manifested and managed in such a coherent and externalized way that he can literally tour you through it -- i.e., the Fortress of Solitude, where through the clear bottle glass he can present to you the restored City of Kandar, reduced to manageable size, and then tour you through the sculptures depicting everyone of importance in his life, resolved into solidity. Superman has no difficulty loving Clark Kent, but he is waiting for Lois Lane to join him in becoming a Clear, which she will accomplish by seeing his two halves as one person.

Batman's trauma is still murky and concealed in a cave. He is not yet a Clear, but he's trying. He needs to give more of his money to L. Ron Hubbard.

R. FIORE:

Well, you know, Jack was Jewish. So is Stan Lee. Their characters would probably have more to do with the Golem than anything specifically Christian. Art Spiegelman once suggested that might with justice also be called "The People of the Comic Book."

R. FIORE:

P.S. And, now that I think of it, so were Siegel, and Shuster, and Bob Kane, and Julie Schwartz, and Sheldon Mayer . . .

Happy Passover, everyone.

SARAH BOXER:

Wow, Jonathan... speaking of brilliant! Geez. I never thought of all this in terms of Freud v. Jung. (And you've definitely got my number here.) Not to go all graphical on you, but I just looked at some online images from the recently published "Red Book," (I've attached one here) and, yes, it turns out that Jung's graphic fantasies are indeed Kirby-esque!

All my scholarship rests on scrupulous study of David Cronenberg's recent movie, of course. That's how we roll, here in academia.

GLEN DAVID GOLD:

Jonathan Lethem wrote: “(The reason Steve Ditko had to leave Marvel was that he subscribed to neither the Freudian nor the Jungian views -- his resistance to seeing the Green Goblin as some kind of familiar and shocking -- Lacanian? -- 'other' for Spiderman being the defining crisis.) Ditko believes he is Ayn Randian. In my view he is Gurdjieffian.”

Geeks will come at you with plastic forks -- Ditko apparently didn't leave Marvel because of the Goblin. He left because Stan and Martin Goodman promised him money they didn't pay. Stan said later it was because of an argument over unmasking Green Goblin, and that's been the refrain ever since. I'm not sure if Ditko ever said his part in print, but numerous people who talked to him face to face have repeated the story: there was supposed to be money and it didn't happen. I've heard Ditko tried to get Kirby to come with.

DOUG HARVEY:

Ha!

Now this:

[Holger Liebs quote:] Mike Kelly’s synaesthetic Gesamtkunstwerk updates earlier holistic Utopias of harmony and universal communication – from the early-20th-century experiments of Russian composer Alexander Scriabin to the multimedia design environments of the 1960s – by introducing another key 20th-century myth of reconciliation and salvation: Superman. The title of the show, ‘Kandors’, references the eponymous city on Superman’s home planet of Krypton that was saved in miniature form under a bell jar by the superhero and transferred to his ‘Fortress of Solitude’ after an evil alien had shrunk Kandor and its inhabitants to the size of a toy. This transportable city-in-a-bottle is emblematic of Superman’s traumatic childhood and symbolic of the double loss he suffered of both his parents and his homeland.

Since Superman trivia have been subsumed into everyday American life – the motif of the Fortress of Solitude, for example, has been quoted in numerous American television series from The Simpsons to Saturday Night Live – Kandor denotes a kind of Utopia, a purely imaginary place, a possible but never actually realized version of a city (Kelley’s installation Kandor-Con of 2000, a kind of laboratory for a future metropolis, was also shown in Berlin, in an abandoned factory on Ackerstrasse). For Kandor is the phantom of a place in two senses: within the logic of the Superman story it is the miniaturized symbol of a traumatic loss; furthermore, since countless renderings of it exist in numerous comic strips, with each version being slightly different, its original appearance can no longer be accurately recalled.

Kelley subjects Kandor to adaptation and reinterpretation within the context of ‘repressed memory syndrome’, the popular mythology according to which the memory of traumatic events could well be completely blocked from the conscious (an idea originated by Freud in his early writings but later abandoned in preference for the repression of impulses theory).

[from Holger Liebs, frieze magazine, Issue 112 January-February 2008]

I don't mean to portray Kirby as some kind of idiot savant. He was a culturally aware individual in his working class autodidact way, and with such unsystematic learning there's no saying what he was or wasn't aware of. In addition, he grew up during the infancy of mass culture and commercial fantastic literature, so classics that touch on the fantastic would be part of his knowledge.

DOUG HARVEY:

Mike's and Jim Shaw's work are both very informed by Kirby's.

JEET HEER:

It does seem appropriate to be talking about Kirby's Jewishness on Passover.

With all apologizes to Michael Chabon, Robert Fiore, and others I think the Golem theme can be overstated. The fact is Kirby, Lee. Siegel, Shuster and others lived as Jewish Americans at a time when public displays of Christianity were even more blatant and unapologetic than they are now. Which meant that Kirby, Lee, etc. would have been aware of many aspects of Christian culture and mythology just by going to the movies (Going My Way, King of Kings, etc.) There is a lot of evidence that Kirby in particular as a visual artist internalized many of the the standard visual tropes of Christianity. Take a look at the cover of Thor #127 ("The Hammer and the Holocaust") and compare it to Michelangelo's Pieta. Kirby's Odin is clearly a counterpart to the Virgin while Thor is a Christ-figure. Kirby used Christian images and narratives with the same reckless aplomb that he used in appropriating Norse mythology in Thor or the pseudo-archeology of Erich von Daniken. For the artist, everything is fair game. More than anything else, Kirby's gleeful larceny aligns him with the tradition of modern art.

JEET HEER:

The recent surge of brilliant comments from Sarah, Robert, Jonathan, and Doug have left me fairly agog, so I'm not sure where even to begin. A few scattered thoughts:

1. I think there is a gender divide on Kirby that we need to be explicit about. Sarah is right to see Kirby through the prism of her son's love of superheros. Spending time with some a young niece and a cousin recently -- a girl aged 4 and a boy aged 5 -- I was struck by how her imagination was totally princess-centric while he was superhero mad. It occurred to me that the dominate Gods or animating spirits of modern childhood, for better or worse, are Jack Kirby (for boys) and Walt Disney (for girls). There sheer pervasiveness of Kirby's cultural impact might be a barrier for appreciating him the way Doug wants, as an remarkable mark-making artist. But any coming to terms with Kirby has to acknowledge not just the historical context that Kirby worked in but also the way his images have circulated through the culture.

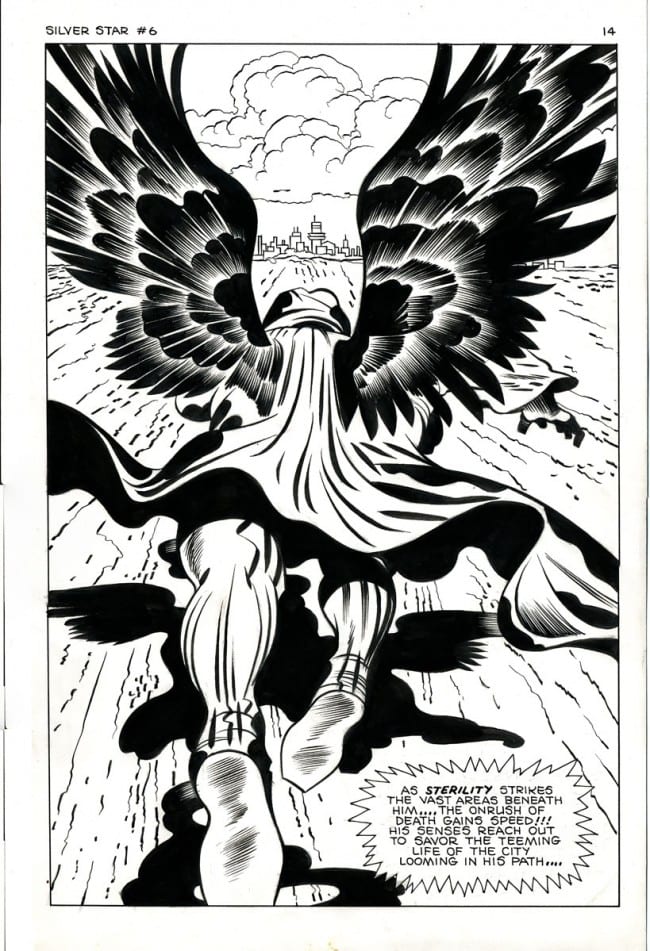

2. Kirby's characters -- especially after the mid-1950s -- tend to be variously scaly, encrusted, earthy, leatherly, scarred, shape-shifting, unstable, chipped, masked, marbled or rocky. I think the psychological inquiry as why this is so is fruitful but I would also add there is a visual component to all this -- it made Kirby's pages livelier than more polished and smooth artists -- I'm thinking here of Curt Swain or the other dominate figures at DC. There is something mysteriously alive on Kirby's page, something that is by no means true of most superhero art.

3. I don't know what to say about Jonathan's Jung/Freud/Rand/Hubbard analysis except to acknowledge its brilliance and to add that like other popular artists -- Hitchcock comes to mind -- Kirby was familiar with at least the more popularized versions of therapeutic culture. As I pointed out before, Kirby did have Mister Miracle fight a creature called The Id. (See Mister Miracle #8). In general Kirby was a cultural sponge who managed to rework virtually everything he saw around him into his visual idiolect. I'll also add that it makes perfect sense to see an affinity, as Jonathan does, between the DC classical heroes and the mythos of Dianetics -- both after all came from the same pulp roots.

4. The Fortress of Solitude ... now where have I heard that before?

DOUG HARVEY:

I feel I should make an aside about my own history with Kirby’s work, because it’s a little peculiar, and I want to avoid generalizing from my own peculiar experiences. I became aware of him at the time of the Fourth World comics – I’d read stuff before that, but wasn’t old enough to be interested in authorship.

I also immediately began cutting up and collaging his comics (fragments of his machinery, explosions, musculature, and sound effects, plus dialogue) into new works, which eventually evolved into a series of collage comic works that continue to this day (in fact I’ll be showing some at Jancar Gallery in Chinatown in LA opening May 19th – any of you in town I’d be happy to meet in the flesh) – so I’m very sympathetic to Hatfield’s emphasis on semiotic analysis, albeit from a formalist practice-based perspective rather than an academic critical one. [For more on Doug Harvey's art see here.]

I became deeply interested in Kirby’s work, and began reading back issues (thanks to a couple of older collector friends) and collecting new stuff as it was released. I was, and remain, a big fan of the reprinted 50’s alien monster stories in Where Monsters Dwell which struck me as very modern in their stripped-down hypnotic repetitiveness. I stuck with him through Kamandi, The Demon, and OMAC, but I rapidly started losing interest with The Eternals and 2001.

This also marked the end of my interest in mainstream comics, more or less, and in the superhero genre – though I’d like to point out that I had finished with the boyhood will to power fantasy phase (or whatever) by the time I was 8 or so. I don’t identify with the embarrassment and defensiveness many comic fans exhibit regarding the genre. But I did feel at the time (and though I haven’t delved much into subsequent iterations, stand by this assessment) that it reached an organic peak with the Fourth World and rapidly devolved into a self-conscious mannerism from which it has never recovered.

So when we talk about Kirby, for me we’re not just talking about an extraordinary artist who shaped and was shaped by commercial comic books for most of their history, but one who presided over (and arguably orchestrated) their death as a valid medium of artistic expression. This is why Kirby remains King and Frank Miller will never be more than an Executive Producer.

A few off-the-cuff thoughts:

1. Kirby's influence on other visual artists is a story worthy of its own book and one that Hatfield only hints at. Within the comics field, this influence has been largely baneful, with epigonic imitators borrowing the surface elements of Kirby to create a synthetic house style (a house style which still undergrids most of the art published by Marvel and DC). Still, there have been creative appropriations and reworkings of Kirby -- notably by Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez as well as Gary Panter.

2. I like the thought of the Fourth World work as the "organic peak" of the superhero genre. If, following Hatfield, we see Kirby as having an essentially apocalyptic imagination, then the Fourth World was the moment of revelation. What followed tended to post-apocalyptic in the literal sense (i.e. stories about what happens after the world has ended: Kamandi, Omac).

3. I'd be curious to know if you've ever revisited the 2001 material, which was widely panned when it came out but now has defenders who see it as the most extreme example of Kirby's formalist experimentation (I think Christopher Brayshaw made that argument in The Comics Journal once).

GLEN DAVID GOLD:

“epigonic”

I'd never heard this word before, and I'm not ashamed to admit it. I am SO going to use it in conversations with people who are better than I am.

DOUG HARVEY:

1. Gary Panter is the MAN!

2. Yes! I'll have to think about that - revelatory ontological

apocalypse transmuting into literal materialist apocalypse. First

there is a mountain, then there is no mountain, then there's a pile of

shit!

3. I haven't. I should. Have they been reprinted? Mom threw them out.

JEET HEER:

About Kirby's 2001 work, alas it hasn't been reprinted (it's virtually the only Kirby work from the 1960s and 1970s that has not been re-issued in the last decade). This is largely, as I understand it, for copyright reasons. The ownership of those comics -- Sony, Arthur C. Clarke's estate -- is murky.

NINE: KIRBY AS BLAKE, BLAKE AS KIRBY

R. FIORE:

The interesting question here is not how Jack Kirby is like William Blake but how William Blake is like Jack Kirby. He is both a poet and a painter. More to the point, he is a printer, which in the 18th Century is to say a publisher. While it isn't mass art, he does develop a method of producing illuminated manuscripts in multiples. Given his revolutionary principles the intent is to create art for an anonymous public rather than to seek patronage among the nobility. The signal difference here is that he makes no attempt to make his art comprehensible to a general public; they would have to come to him on his terms, and they didn't. Robert Christgau coined the term semipopular art, meaning that which has every characteristic of popular art except popularity. William Blake might be said to be the father of semipopular art.

Imagine a William Blake born in Lambeth in 1917. During the war he's producing graphics for the Ministry of Information. He's known in bohemian circles as a talented fellow but a bit of a roughneck and not quite the right sort -- his father was in trade, after all. After the war he picks up a couple of bob here and there drawing and writing for the comic weeklies. Eventually he lands at The Eagle and then in the 1950s it's Hampson, Bellamy, and Blake, and Blake is the one who writes his own scripts. He gets talked to about the unorthodox religious ideas that get into his scripts. Frequently. You know he's going to be one of the first people on Earth to take LSD. And then as '60s start to swing, which old stager do you suppose is poised with the means and motive to blow open the doors of perception . . .

JONATHAN LETHEM:

I love this.

DOUG HARVEY:

Sweet.

GLEN DAVID GOLD:

This really is beautiful.

I just saw a piece by Freeman Dyson in the New York Review of Books (hey, don't worry, I just get it for the cartoons) that references Blake in discussing the difference between physics insiders, those with connections to the academic world, and outsiders -- educated and intelligent people who have theories that are wonderful and not based on science. Not schizophrenics (though the Museum of Jurassic Technology has a wonderful book on schizophrenics' letters to astronomers), but people whose work relies more on a poetic soul than what's experimentally viable. The instant response is "crackpots" but Dyson doesn't see it that way. He keeps coming back to contemporaries' opinions on Blake, and I read the comments below back to back with what he said, which was nice on this Matzo Bunny of a day.

DOUG HARVEY:

Was he reviewing this?

GLEN DAVID GOLD:

Yes he was.

I hope these come through. I only realized this comparison 5 minutes ago and I'm sorta gasping.

TEN: KIRBY AND MODERNISM

DOUG HARVEY:

I guess I won’t have time to get down all the thoughts I’ve had reading Hatfield’s book and the previous emails, but if I’m not already too late, I’ll put in my final two cents. As some one who is not immersed in comics culture, I really appreciate the balance of historical information, critical opinion, and academic contextualization Hatfield manages. I imagine it will go a long way to foster acceptance of the comic book medium in American academic circles, which is probably a good thing. I like that his more theoretical flights are in the realm of semiotics, as it’s the only sub-category of post-'70s critical theory that holds much interest for me, and certainly the most applicable to comics. I think it might have been better to elaborate on Charles Peirce (Chapter 1) even further along the narrative momentum of Kirby’s biography, and I think the Umberto Eco section (pp 126 - 128) could be expanded significantly, particularly to The Fourth World, and Kirby’s inability or unwillingness to wrap things up neatly.

One of the central and most challenging insights of Modernism is the recognition that -- however much our minds and hearts desire it -- life doesn’t happen in static, compartmentalized, narratively resolved units, and that any attempt to represent reality has to take this into account. The disintegration of The Fourth World through the proliferation of potentialities reminds me of the perpetually unraveling plot of Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (from 1973), and also of the rapid evolution and disintegration of Free Jazz (Albert Ayler died in Nov 1970, when Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen #133 was on the stands), which took the vernacular conventions of its populist roots and subjected them to fragmentation, repetition, compression, and elongation – toward an infinitely receding horizon of resolution.

I was particularly impressed with the period of Fourth World titles when they were expanded to 48 or 52 pages to include reprints of Golden Age Simon/Kirby stories, and odd episodic sidebar stories like Young Gods from Supertown, which imposed an even more un-wrap-uppable cross-generational simultaneity on what was already an exponentially diverging rhizome of storylines. One of the generally forgotten major preoccupations of the early modernists (including Marcel Duchamp) was the possibility of giving material expression to time as “the fourth dimension” – my sense (and this may be a sign of my own mental problems – I also think that the Don Rickles clone “Goodie” Rickles was a brilliant character) is that Kirby shifted his own interest in this problem from the technological sublime Hatfield describes (“I’m actually witnessing a four-dimensional universe!” – Reed Richards, p 158) to the structure of the medium itself.

ELEVEN: KIRBY AND GENDER

SARAH BOXER:

Hi All -- If it's not too late...

Before the men’s locker closes up to me forever, I’d like to speak up as the token gal here. I’ve been truly honored to be allowed in as you all discuss manly and boyish stuff like Cap and the Fourth World (even if I have had, at times, to ride on my son’s coattails to do it). But now I have a little confession to make. Ahem.

The only bit of Kirby’s work that I actually even kind of halfway enjoy reading is the romance comics. I know. I know. I’m a hideous stereotype of my fair sex. Well, so be it. From reading Hatfield, I understand that these romances were the bread n butter of Kirby and Simon’s comic book business (before Kirby joined Marvel). So I’m not alone here. Many people who were repelled by other Kirby comics must have gobbled these romances up like candy. Sour candy. Superego candy. I see I’m using a lot of eating metaphors. It’s time for dinner...

Okay, now I'm back.

One appeal of the Simon and Kirby romances is that, as Hatfield observes, Kirby put a lot of his class anger into them. Look at the comic titled “Shame”. The woman who stars in this episode tries to pretend she comes from a high-born family in order to win her high-born man. She ignores her own low-class mother when she collapses in the street. In the end, the girl’s shame at rejecting her own family becomes stronger than her shame of her family. She trades one sort of shame for another. She goes back to her family and gets her man too.

The same message is pounded in over and over in the romances. Shame. Shame. Shame. (Here’s the plot of “The Perfect Cowboy”: Small-town girl falls for a smooth-talking big-time movie-star cowboy. But in the end she goes back to the boyfriend she grew up with. He’s like a comfy shoe. She never should have tried for a fancier shoe.)

These romances are period pieces; they are dated, in a way that Captain America is not. The figures remind me of something out of a Vogue pattern book. Different bodices. Different trim. Different moral high-grounds. They also look just like the kind of comic that Lichtenstein used to use (and maybe mock) in his paintings. (It's hard to imagine Lichtenstein copying Cap or The Hulk.) The only variations are the different settings, different hair colors, different clothes, and the different variations of moral blindness: Why don’t you try on this kind of shame for a change?

I kept thinking of a line from Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz. "If I ever go looking for my heart's desire again, I won't look any further than my own backyard, because if it isn't there, I never really lost it to begin with." Which actually makes no sense. But the moral is clear: Stick to your roots. Don’t strive. If the superheroes are Kirby’s id, these romances are his superego, his mother, his moral roots. (There's something to be written about the mothers of cartoonists, but that's for another day...)

These stories are dreadful in a way but also kind of wonderful. As I’ve noted before, one thing I find literally repellent about the Marvel superhero universe is the nauseating, clanking weight of each character’s history -- the way these stories resemble soap operas. Soap operas for men. So it’s kind of ironic that one thing I particularly like about Kirby and Simon’s romances is that these too resemble soap operas, but in a different way. They aren't heavy like soap operas. They are light like soap operas. The stars of the romances have no history. Without any background whatsoever, you can pop into them and pop out of them. Each woman is any-woman -- spunky but tame, campy but prim, the girl next door with a sense of adventure. And like soap operas, they are trashy, compulsive

entertainment.

That's it. I've weighed in as the token gal. It's been fun hanging out in your locker room.

DOUG HARVEY:

I [heart] romance comics too!

TWELVE: KIRBY AND DITKO

R. FIORE:

Before we wrap there's something I'm a little curious about. Going in my assumption would have been that while Kirby was the more accomplished of the two, Steve Ditko would be considered essentially in the same league. I would have seen them as rough-hewn talents who produced significant bodies of work in adventure comics in the period when newspaper comics were no longer hospitable to adventure -- not that either was sufficiently genteel for newspaper comics in the best of times. I assumed it was the consensus that the two were basically comparable. But I note Jonathan Lethem speaking of "[T]he Fiore side of things (Kirby is "like" Steve Ditko, Stan Lee, Gil Kane, etc. . . ." in such a way as to imply (if I don't misinterpret) that Kirby is on a higher plane. Anyway, what I was wondering is, would the panel consider Kirby and Ditko to be peers or do you consider Kirby to be on another level altogether?

DOUG HARVEY:

Kirby's a better visual artist. And while I love Mr. A, I find Ditko's imagination to be somewhat more paranoiac and addicted to rationalization than Kirby's more generous and open-ended vision.

DAN NADEL:

I just wanted to chime in here and thank everyone for such a great roundtable. I'm sorry to have been absent the last couple weeks -- our newborn baby has consumed all my time (surprise!).

But, I can break long enough right now to say that I'd put Kirby above Ditko as an artist and writer. But I'd place Ditko ahead of Kirby as a uniquely observant cartoonist whose ability to imbue his characters with nuanced emotions (well, between 1960 and 1970, say) is hard to top. Also, Ditko's psychedelia was more delicate (and way more influential) than Kirby's, which I appreciate, though this is a minor point. Suffice to say that for scope, vision, and level of achievement, Kirby wins out. Ditko remains a fascinating story, though, and one that is mostly untold.

GLEN DAVID GOLD:

What Dan said (if I write a book about comics, it's going to be called "what Dan said" except when he disagrees with me).

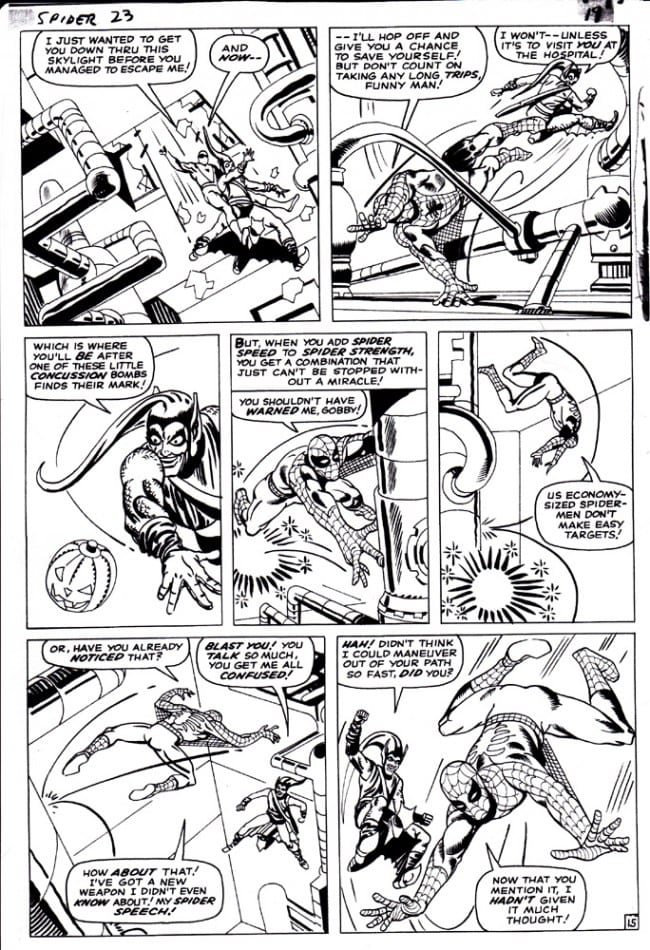

But also maybe this: I have framed on my office walls about six Jack Kirby pieces (that number keeps changing) and three Ditko Amazing Spider-Man pieces. When collector folk come around, they react to one or the other of artists from nostalgia or aesthetics or narrative or something else. My wife, however, hates Ditko. She has a very good eye for abstract art and photography, and has led me many places I would never have gone. When I asked her why she preferred Kirby (and she would probably dicker with the word "prefer," as she's more of a Lynda Barry/Edward Gorey type -- she gets my interest in Kirby) she went to this page and told me exactly why it sucked:

She pointed out that unlike Kirby, Ditko doesn't make allowances for how they eye travels from panel to panel. The motion is chaotic and when you look at the page design as a whole, there's a lot of interruption to the flow. And even though Jack's anatomy is often crazy, it makes sense emotionally. She tapped the Goblin's arm in panel 3 and pointed out that it makes no sense, and that unlike Kirby, there's no hyper-realistic reason for it making no sense. I had her read a few early ASM issues and she tossed the Essentials back with a shrug. "Dude is frightened of women." True. Kirby wasn't. (He also, unlike every cartoonist I can think of, never drew porn. Even Romita did a nude Medusa. Some of Kirby's women are erotic, but there's never as far as I can tell been a Kirby nude. Mebbe too big a kettle of fish to open here at the last minute, but I've always been curious about that.)

I think Ditko's plotting, emotional engagement, humor, expressive gestures and overall weirdness make him interesting. I've wondered how working with Stanton influenced him (I read Blake's book but can't remember that information too well). I have a Ditko/Stanton piece that's typical of theirs. For six years, it looks like when Stanton drew his femmes fatales, Ditko drew the men being menaced and overwhelmed and whatnot. Now there's a division of labor.

BTW, speaking of nothing, I went to the Clowes show at the Oakland Museum last night. Holy smokes! Has anyone ever noticed that guy is a good artist? Because he is.

JONATHAN LETHEM:

It's funny, because in my general thinking I always rate Ditko so high, but when I glance at pages now I tend to find myself thinking, "This must not be the best work, there must be something more consummate that I was thinking of" -- Ditko's style always seems "too early, he's getting to where he wants to go but he's not there yet" or "too late, he's tightened up and is repeating himself," but never reaching fulfillment. Still a master -- paranoid, baroque, psychedelic, and inimitable, but being asked that question after dwelling for these past weeks on Kirby's breadth and generosity and development and influence -- even despite his identifiable limitations or sloppiness -- it feels a bit like being asked, "Who's the better band, the Rolling Stones or The Buzzcocks?" I mean, nothing against the Buzzcocks, I love 'em. But.

JEET HEER:

I think the Rolling Stones/Buzzcocks comparison is fair enough. Ditko is one of the most interesting artists ever to work in mainstream comics but Kirby is a universe onto himself. Or to put it another way, Ditko is Harold Lloyd to Kirby's Charlie Chaplin. It's no knock on Lloyd -- whose movies are all worth watching -- to note that he's not as universal and inescapable as Chaplin. Or Ditko is Ben Jonson and Kirby is Shakespeare. Or Ditko is the Three Stooges and Kirby is The Marx Brothers. Or maybe I should stop.

GLEN DAVID GOLD:

I just realized this: Unlike Ditko (and most of the other comic book artists you can compare to Kirby), when we think of Kirby we eventually say he's like Dick or Blake or Miles Davis or Jimmy Stewart or Henry Darger or his work is like constructivism or futurism or iconography. Something about Kirby makes us want to find an analogy for him and all the analogues seem to have big holes in them so far. Could be why we've just don’t 24,000 words on him and I bet we could do 24,000 more.

CONCLUSION

JEET HEER:

Glen is of course right that this discussion could go on much longer. Nearly twenty years after Kirby’s death, the cartoonist still looms as large and nearly inexhaustible figure who continues to inspire both passion and resistance. I’m grateful to all the roundtable members. There have been many memorable moments in this discussion – not to pick favorites but I relished how Glen zeroed in on Kirby’s war years as a crucial biographical turning point, Jonathan’s ode to Kamandi #10, Robert’s fantasy about Blake living through Kirby’s era, Sarah’s insight into class shame as the engine of the Simon and Kirby romance comics, Dan’s focus on Boy’s Ranch as Kirby’s first big expansion of his artistic range, and Doug’s insistence on seeing Kirby as a visual artist. I also want to add that I personally found Hatfield’s book a great jumping off point for thinking about Kirby and comics in general. Virtually every page of the book offers a fresh way to think about comics as a visual storytelling form. Throughout the discussion, I’ve tried to play the devil’s advocate and occasionally give voice to the nay-sayers who find Kirby to be too bombastic an artist to be taken seriously. But one measure of an artist’s worth is the amount of intelligent commentary his or her work generates. By that criteria, Kirby’s reputation is in good shape and continues to grow.