This conversation between artists Jack Davis and Jim Woodring took place in 2000 and was published in The Comics Journal #225.

This conversation between artists Jack Davis and Jim Woodring took place in 2000 and was published in The Comics Journal #225.

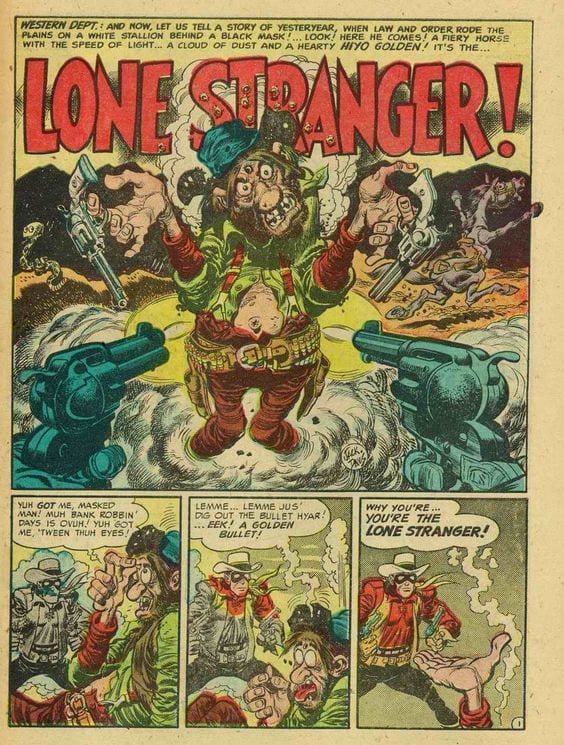

In my sweet naiveté, I’d assumed that readers of The Comics Journal needed no introduction to Jack Davis, one of the handful of cartoonists who gave the old EC comics, especially Mad, their distinctive, protean appeal. However, a few carefully placed feelers among younger cartoonists of my acquaintance revealed to me that his name and achievements are unknown to many of today’s vigorous young bulls, though they all had seen his work. “Oh, that guy,” they’d say when I trotted out the old Mads.

There probably isn’t a person with eyes in America who hasn’t seen Davis’ stuff. For the past 50 years, he has churned out an unbelievable number of comics, cartoons, ads, magazine covers (notably Time and TV Guide), movie posters and illustrations. Offhand, I can’t think of another illustrator who has achieved and maintained for so long such a high level of visibility.

When I was a lad, Jack Davis was the cartoonist I wanted to be. To a clumsy but ambitious youth, his skills were miraculous. He could draw loose or tight, humorous or serious, straight or zany: in brush, pen or pencil. He could caricature brilliantly. His painting style was stunning, seemingly intuitive and utterly delicious. Even the elements of his work that were obviously dashed off sparkled with virtuosity.

I had heard that he was unbelievably fast … that he painted with mud when watercolors weren’t available … that his pencils were negligible … that he produced comps on demand in waiting rooms and offices … that he used a children’s watercolor set to do his paintings. What a guy! I was dying to meet him.

I finally got the chance earlier this year at a symposium hosted by the Savannah College of Art and Design. Seventy-six years old, in great health, sharp of wit and firm of hand, he was the very picture of a Grand and Venerable Practitioner. He showed slides of some of his recent work, most of it sports-related, talked at length about his career and patiently answered a slew of dumb questions.

He was perfectly friendly and accessible, but one felt that he was playing ’em close to the vest. Everything he said was interesting, but there were no spontaneous outbursts, no forays off the beaten track. This tallied with his reputation as a soft-spoken Southern gentleman who went to considerable lengths to avoid ruffling feathers and who was disinclined to say anything bad about anyone except General Sherman.

Still, I jumped at the chance to interview him. I had an idea that I could get him to open up a bit and tell some gritty anecdotes. After all, he had been present for nearly the entire life of EC’s vaunted run of horror, science-fiction and suspense comics and had, I presumed, a lot of first-hand information about the quirks and peccadilloes of the other EC artists and editors. I was hoping to coax from him stories of, say, a bleary-eyed, Ghastly Ingels cutting macabre capers at staff parties, or of Bill Elder pulling creepy pranks, or of a soused Wood acting badly.

Alas, this was not in the cards. Predictably, Davis declined to tell tales out of school. As often as I offered him the chance to dredge up some juicy, salacious story he never rose to the bait. His reputation as a gentleman of the first order remains untarnished, despite my efforts to drag him down to my level.

And upon reflection, I’m glad it turned out that way. He seems to be the kind of man who would fret over indiscretions, and who would suffer if he thought he had been unkind.

As you’ll see, the interview came to an abrupt end well before I had asked all the questions I’d wanted. I intended to resume the proceedings later but then decided not to pursue it. All along I’d had the feeling that for him the interview process was a bit of a bore to which he had graciously acceded but which interested him not a whit. Rather than impose on his good nature further I chose to let it go; it was plainly the gentlemanly thing to do.

— Jim Woodring

JIM WOODRING: I’d be interested in knowing what artists you looked at when you were coming up and you were developing your skill, what artists you are interested in now if you are a museum-goer: if you have any favorite old masters. If you are interested in fine art, if you’re a Sunday painter. I’m interested in how you feel about art beyond specifically what you do as a cartoonist and an illustrator. I wonder if you ever do paintings that people might consider serious paintings, serious spiritual paintings or anything like that. [Pause.] I realize that’s a lot of questions.

JACK DAVIS: I would like to probably do some watercolors on my own. I liked to do old filling stations, old houses, things like that. And I’ve always wanted to do a children’s book on my own. You know, write it and maybe draw it, but I’ve never done that. I probably never will. I enjoy going to museums if they’ve got interesting paintings. I like certain paintings. My wife likes that landscape here in the lobby that’s very nice. She likes certain things. I like certain things. We never really agree. [Laughs.] I have always been open to going to museums and looking around. I went to Paris. You could spend a week at the Louvre to see the old masters’ paintings. I like Daumier. I like Heinrich Klee.

WOODRING: Aha.

DAVIS: I said yesterday that Walt Disney was always an inspiration. Segar who did Popeye. Alex Raymond and Harold Foster. I know that they were pretty straight illustrators, but in their work, I can see things — action and stuff — that lead to cartooning. The anatomy was great. When I was in college, when I got out of the Navy I took fine art. They didn’t have a commercial art course. And I took life classes over and over to learn the figure. I really wasn’t good at it, but that paid off. Back in those days, they did not have cartoon schools or anything like that. What I’ve picked up is just what I’ve enjoyed drawing and seeing. My sense of humor’s kind of wild. I like to kid people, tease people … My wife says I’ll never grow up.

WOODRING: That’s great.

DAVIS: I’ve never been good at school academically. I always got through by the skin of my teeth. I never graduated from college, but I had four years on the G.I. Bill, which was a pretty good education. I just had a good time. Life’s a good time.

WOODRING: Sounds like you’ve had an absolutely wonderful career. I liked it yesterday when you said you felt you’ve been unemployed all your life.

DAVIS: Yeah. I have. I think the only steady check that I had was when I was working with Hefner. Hefner would send out a check just once a month or something like that, but it didn’t last that long.

WOODRING: You said that you took a lot of life drawing classes at the Art Students League in New York.

DAVIS: Not a lot. When I went up to New York, the Art Students League was crowded with veterans. I think most of them were there to get the money and to see the models. But my life drawings really came at the University of Georgia, where I did it over and over and over. They weren’t nude or anything. They used clothes or drapings and we drew a lot, sketched a lot.

WOODRING: Have you ever felt the need to take any kind of a touch-up course in anything?

DAVIS: Hmm … touch-up?

WOODRING: Well, sometimes artists will feel that, after they’ve been drawing for a long time, they’ll feel that, “Oh, I should take another anatomy class.”

DAVIS: I think it’s just what you see and what you draw. And I’m very critical of what I draw. I mean, after I do something I’m very disappointed because I want it to look better. I see other people’s work, it’s beautiful, and I don’t see how they do it. They’re very realistic. But I’m not too impressed with any cartoonists, like in the old days.

WOODRING: You mean newspaper cartoonists?

DAVIS: You know, cartoonists now that draw like in the old days. There was one … Cisco Kid. The story wasn’t that great, but the drawings were beautiful. And now you open the pages and it’s just the same repeating and repeating. They go on gags more or less. I loved Gary Larson who did The Far Side. His artwork was great. It was good. I mean, it was funny.

WOODRING: It was funny.

DAVIS: And nobody could draw like that. Calvin and Hobbes was good. That’s really it. And I like [Jeff] MacNelly, you know, the editorial cartoonist.

WOODRING: Sure. Sure. Do you know Pat Oliphant’s work?

DAVIS: Yeah. He’s from Australia, I think. I know his work.

WOODRING: Do you like it at all?

DAVIS: I like it. I like it. It’s had a big influence from Mad.

WOODRING: Oh yeah. Yeah.

DAVIS: They all kind of fall into a little bracket of pen and ink and that Craftint, Zipatone. And the more you draw the more you get it. I think that if you look back at a lot of my work and stuff, it’s pretty crude. But you draw and draw and draw you’re bound to get a little better.

WOODRING: Well with your work, and like I say I’ve got a lot of it, sometimes it seems like you had less time and sometimes it seems as if you had more and that’s a big difference.

DAVIS: Well, it depends. If you’ve got a deadline and you whip it out, bat it out, and it’s not any good. And sometimes I overwork something. You’ve got to really enjoy it. I like to look forward to getting to the drawing board because I know where it’s going to come out, why it’s going to be printed and I want to do a good job.

WOODRING: Of course. Do you still get a charge out of seeing your work in print?

DAVIS: Oh, I still get a big kick out of that. I do a program at football games in Georgia. You sit around and you see people who’ve got the magazine and you want to say, I did that. You don’t.

WOODRING: [Chuckling.] No, you can’t do that. You mentioned Clifford McBride who drew Napoleon, among other cartoonists of that era. One of the thing that almost frightens me is to think of all the great work that’s been done in this century that’s just disappearing into the sand. Especially around the turn of the century, there were cartoonists like T. S. Sullivan …

DAVIS: Yeah.

WOODRING: … who’s one of my big favorites. Iggy Frost.

DAVIS: Oh, yeah. Frost. Oh my God, he was great …

WOODRING: They achieved so much and they’re practically unknown today. But I don’t think that’s going to happen to you because your work has been involved in so many… You know, Mad magazine, it seems kind of weird, but it’s like, a huge cultural thing. People will never forget it.

DAVIS: That’s funny. It hit a spot in communications in whatever way, but Mad just really took off.

WOODRING: It did. And your style in particular. I’ll sometimes say to somebody, “Oh, I really like the work of Jack Davis.”

And if they don’t know cartoons, they’ll say, “Who’s he?”

And I’ll say, “Oh, you’ve seen his work. He drew this.”

And they’ll go, “Oh, it’s him.” So if they don’t know your name, they know your style.

DAVIS: But I liked George Baker, I liked Hank Ketcham. You can’t dismiss the design of them. The guys working for him are also good. But I could never have anybody working for me. If I make a mistake I want to make it. I do what I do.

WOODRING: So you’ve never had an assistant or an apprentice or anything like that?

DAVIS: No. Never. I think a couple times, going into New York, when I was probably late with a deadline going to Mad, or to EC, back in the old horror biz, and I’d drive from Westchester into Lafayette Street, way down at the other end of the island, and I had not erased my pages. And my wife, who is not an artist, who doesn’t really care anything about cartooning or anything, she sat in the back seat with an eraser and erased the pages before I’d take them in. Because it would take about an hour to get into town, an hour or more. She’d sit in the back seat erasing them.

I used to go fishing with a buddy of mine. We’d go up into Vermont or New Hampshire. I was doing bubblegum cards for Topps Chewing Gum.

WOODRING: Oh, right. Yeah. I have some of those.

DAVIS: And I had a deadline to get that in, but we were camping out. No electricity or anything. I sat in the headlights of the car and started drawing little baseball cards.

[Woodring laughs.] Well, I’ve had some real experiences.

WOODRING: I heard a story once, and I’ve always wondered if it was true, that you were on a camping trip and somehow some editor contacted you and wanted you to do a painting real quickly. So you did, and you used water that had mud in it from the lake, and…

DAVIS: Oh yeah. One time I used bourbon or something.

WOODRING: Oh, that’s good. [Both laugh.]

DAVIS: I think it was that one time only. I mean, I haven’t done that frequently. But I’ve enjoyed it. It’s been a good, full life. I’ve been very lucky. As I say, I’m blessed, but I’m lucky.

WOODRING: All of us who love drawing have been blessed by having so much of your work around to look at. It’s made a big difference. It’s kept a lot of cartoonists going, just the energy in your work. For a lot of people, it’s a struggle to draw. And you’re proof that it can come as naturally as breathing, as everybody knows how fast you are and how much you love it.

WOODRING: All of us who love drawing have been blessed by having so much of your work around to look at. It’s made a big difference. It’s kept a lot of cartoonists going, just the energy in your work. For a lot of people, it’s a struggle to draw. And you’re proof that it can come as naturally as breathing, as everybody knows how fast you are and how much you love it.

DAVIS: I don’t know how to explain it. Again, I can sit down and make real quick sketches and go right in. It just comes. I don’t labor over anything at all. It kinda goes fast. It’s always been that way.

DAVIS: I don’t know how to explain it. Again, I can sit down and make real quick sketches and go right in. It just comes. I don’t labor over anything at all. It kinda goes fast. It’s always been that way.

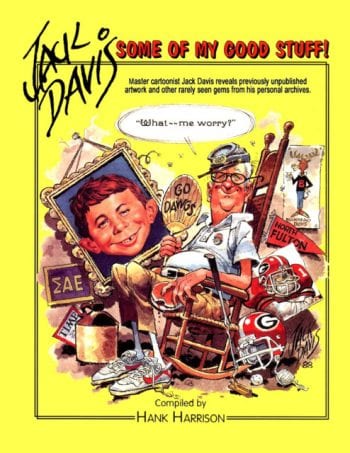

WOODRING: That must be what makes it sing like it does. There’s that book of your work called Some of My Good Stuff.

DAVIS: Yeah.

WOODRING: I saw that and grabbed it right away, and then I was so happy to see that a lot of it was idea sketches and quick drawings, that really captured your line.

DAVIS: All of the stuff that I send over the fax machine … I usually Xerox it on a copy machine before I take a pencil and I copy it on the Xerox because it comes out blacker. I’ve got a stack about that high of just regular writing, you know, typing paper, with all of these sketches on it. Someday I’m gonna weed out the good and the bad because some of that’s my best stuff.

WOODRING: [Ecstatically] Oh. Well, I love that collection. Just being able to see your line right out of the brain so to speak. That’s wonderful. I wanted to ask you a couple of questions really quickly about Mad and EC in general. One of them is that everyone knows that Harvey Kurtzman was a stickler for detail.

WOODRING: … and made you get everything just right. Would you say that that brought better than average performances out of the people he worked with?

DAVIS: I think it did. Harvey was a great teacher. Really. And a great artist. He would teach you, say “This doesn’t read well,” or something like that. And it didn’t read. I’d overwork it and he would simplify. And I’d say, “Oh, I liked that thing.” But if you simplify it reads better, and it looks good. So he taught me a lot. It’s just a shame that he didn’t get more recognition than he did.

WOODRING: Yeah. That always seemed very sad to me that Gaines did so well and Harvey had such troubles. I have to ask you something about the horror comics: I’ve heard you say that you felt bad about doing them. Was that simply because you had a professional attitude? Did you enjoy doing them, but felt bad about the problem that they might cause?

DAVIS: As a kid, I loved ghost stories. I loved Frankenstein. That scared the hell out of me and I love that. It was just so great.

WOODRING: Me too.

DAVIS: So I learned to draw it. It comes out that way: gruesome. I guess that’s the bad side of me ...

WOODRING: Well, I don’t think so. What I want to know is did you enjoy …

DAVIS: [Interrupting] But I’ve never been that. I’ve never been one to draw romantic things or sweet or nice things. I’ve always drawn grotesque things.

WOODRING: I guess that’s why I like it so much. I’m wondering, when you were drawing those horror stories, if you felt bad about doing it, or if you were worried about the bad effect they might have on society?

DAVIS: When I was doing it, I just cranked it out. Like I said the other day, I just turned it out and you’d get paid. And I figured everybody else was doing it, so I did it. Some of the stories I didn’t particularly like, and of course my wife didn’t like it. I drew it and I was good at it. It didn’t bother me too much. What bothered me later was with Mad. Like when people would come up and say certain things, or draw pictures of people in bed together and the whole…

WOODRING: It all changed.

DAVIS: It’s just the way things are going now.

WOODRING: It is, unfortunately.

DAVIS: I just don’t know if my grandchildren will read it and say, “That’s your dad,” or something. And I did that with Playboy. I did the gags when my kids were just born, or just going to school. I never did anything real risqué in Playboy. I did something like Johnny Mercer singing … make it one for baby and one for the road. And a guy standing at the bar with a baby. And like Sherwood Forest, Robin Hood speaking at an old gangly bartender or something. I enjoyed doing things like that.

WOODRING: I have a collection of those. Those are the pictures that I used to cut out of Playboy. The cartoons.

DAVIS: But Johnny Mercer’s wife. You know, he’s from Savannah. Johnny Mercer.

WOODRING: Oh yes, I read that book.

DAVIS: His wife put out a book of all of his songs and lyrics, and she reprinted that cartoon.

WOODRING: Oh did she? Great.

DAVIS: She didn’t know who I was or anything.

WOODRING: When I was a boy I knew this man named Gene Moss, who was a voice actor. He did a record called Dracula’s Greatest Hits. I was a fan of his, so I sent for this record. And when it came, you had done the front cover and the back cover and a set of cards on the inside. And I must have been 13 at the time, but I still remember the joy I felt when I got that record and saw that it had a bunch of your artwork. Your pen-work with all of the lines and outlines.

DAVIS: I don’t work with a pen like I used to. I did a lot of things for Random House. God, I knocked myself out. Random House had never really done a children’s book then. Random House was a big outfit that did North American Indians, and I love Indians. And did some stuff with Abe Lincoln and the Civil War. I forgot about that.

DAVIS: I don’t work with a pen like I used to. I did a lot of things for Random House. God, I knocked myself out. Random House had never really done a children’s book then. Random House was a big outfit that did North American Indians, and I love Indians. And did some stuff with Abe Lincoln and the Civil War. I forgot about that.

WOODRING: Oh yeah, and your Humbug work is that way too.

DAVIS: It was the pen and ink. Now if I do something like that, I still enjoy it, but I’ve got to get my hand going, just like warming up in baseball or something like that. You’ve got to get that hand going and then it flows. But if you start right off, it doesn’t.

WOODRING: Do you ever sell your originals?

DAVIS: No, I haven’t. I give them away, sometimes, but I have a big collection. And what I’m going to do is probably give them to my kids. They can do what they want to with them. Sell them or whatever. I had some stuff at Sotheby’s, you know, that I gave. Some of it went pretty good, some of it didn’t. Again, it’s how they present it to people at auctions. Some people are interested; some are not. A little disappointing, and yet I was pleased to get an offer when you see what it goes for and what people like.

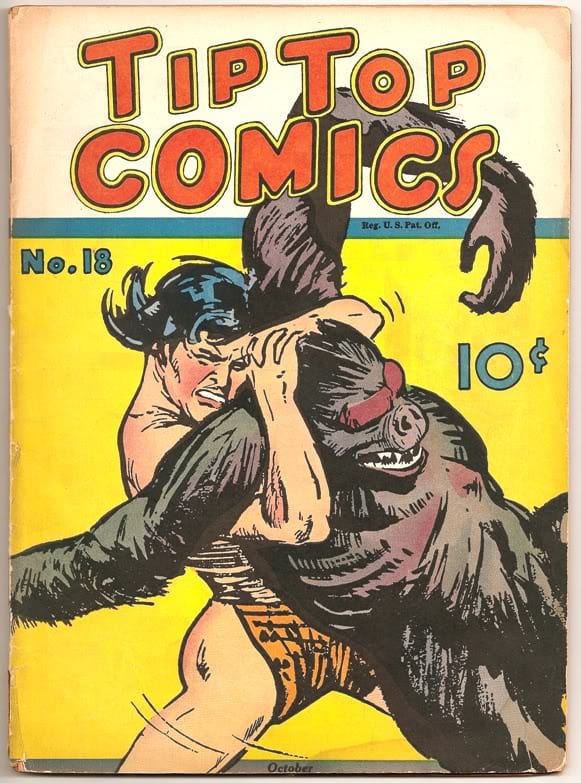

WOODRING: In that book of Hank Harrison’s called The Art of Jack Davis, there’s a reproduction of a four-panel comic that you did at the age of 12, I think. It was printed in Tip Top Comics. That was your first published work, I guess?

DAVIS: Right.

WOODRING: Do you remember when that came out?

DAVIS: Somebody sent me the Tip Top comic books, and I’ve got it here somewhere, but it seems like it was back in 1937 or something.

WOODRING: Do you remember being a kid and seeing your work in print for the first time? What a blast that was?

WOODRING: Do you remember being a kid and seeing your work in print for the first time? What a blast that was?

DAVIS: Oh sure. I got a big kick out of that.

WOODRING: I’ll bet you did. So I guess by the age of 12 you made up your mind to be a cartoonist.

DAVIS: Right. And I think I got a dollar for that drawing.

WOODRING: Probably a dollar went pretty far in 1943.

DAVIS: And in the front of the magazine, Tip Top Comics, they had Tarzan by Harold Foster, and my God, he was my idol. I pored over every little brushstroke he made because I couldn’t draw like him, but I sure loved his work. But he was in that issue of Tip Top Comics.

WOODRING: He was? Was he doing Prince Valiant for that?

DAVIS: No. This was before Prince Valiant.

WOODRING: Wow! So that must have been a thrill, to be in the same book as your hero, there.

DAVIS: Oh, lord yeah. But mine was so crude, it was embarrassing. But evidently they printed it.

WOODRING: Well, it looked pretty good to me for a 12-year-old. It looked amazing. Did you take any kind of correspondence course or get any other kind of …

DAVIS: I did once, and it didn’t last too long. I think it was the same course that Sparky Schulz took, too. I could be wrong, but that was about the only school or correspondence back then that was around. I don’t think there was a cartoon school. So I sent off for that and it lasted for a while. Then it cost money and I think it got to where either I couldn’t afford it or I lost interest in it. I think they offered me a job to help correct drawings or something like that at the end. They sort of promised to find you work when you finished your course. It never happened.

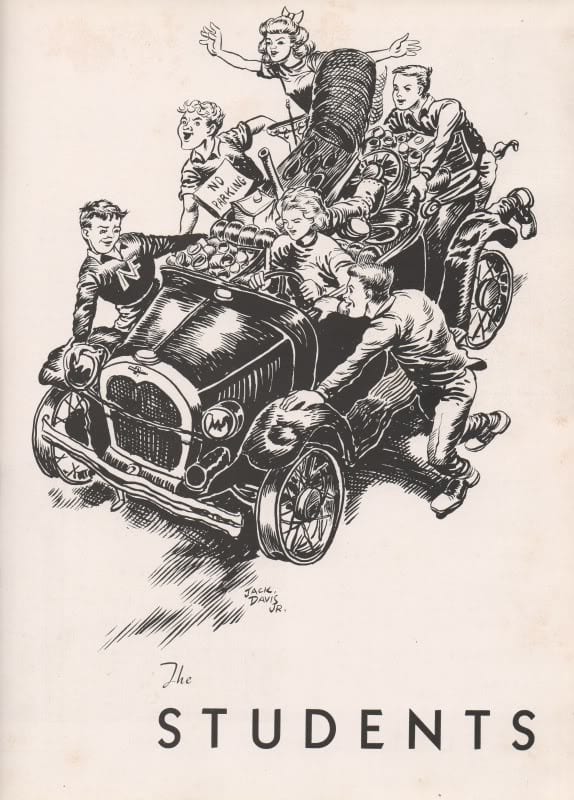

WOODRING: In that same book, there’s a drawing that you did for your high school yearbook of a bunch of kids pushing an old flivver, it looks like a scrap drive or something.

DAVIS: Right. That was the old scrap drive, where, you know, World War II, they were trying to get all the metal that they could to make into weapons and all that bit.

WOODRING: Right. That’s an amazing drawing for a high school kid. It’s really ambitious, and it’s obviously your style, even then.

WOODRING: Right. That’s an amazing drawing for a high school kid. It’s really ambitious, and it’s obviously your style, even then.

DAVIS: Well, it’s kind of gruesome.

WOODRING: Your style is? Gruesome?

DAVIS: Well, I don’t know. To me. It was there. I don’t know why, but I was just lucky I guess to have it in the yearbook. I had a teacher who liked my work and I did posters for different activities — football, basketball and whatever came up.

WOODRING: What amazes me about that drawing is that it’s recognizably a Jack Davis drawing. You’ve probably been asked this a million times, but where did that style come from? Do you have any idea?

DAVIS: Again, it comes from Walt Disney, I think. And Popeye, and then again Harold Foster, the action shots and the feet. And Alex Raymond — just everything he did was a beautiful piece of work. You just don’t see that anymore.

WOODRING: No, you don’t. But I don’t really see a lot of Disney or Segar in that style. It looks like you had a conception of how to draw faces and people and hands and postures and everything just …

DAVIS: [Interrupting.] Jim, it’s hard to explain. I wish I could explain it.

WOODRING: I appreciate you trying. I realize it’s kind of an idiotic question, but it’s something that’s been chewing away in my mind for years. Because it just seems so natural, so perfect, and it’s spawned so many imitations.

DAVIS: There was a book, and it was kind of a fairy storybook, and it was beautifully illustrated about a giant, a great big giant, and he had large feet and hands. And I think that impressed me, too, sometimes. You know, the old fairy[-tale] books and children’s books.

WOODRING: Right. You wouldn’t by any chance remember the name of the illustrator who did that book, would you?

DAVIS: I wouldn’t. I’m sitting right here now, and there’s just no way. Like I say, I’m getting to be 75, and it’s bad to remember anything. [Laughs.]

WOODRING: OK. After you went to the Navy and you went to college, you went to study at the Art Students League in New York. Is that right? Around 1950 or thereabouts?

DAVIS: I went to the University of Georgia, and took fine art on the G.I. Bill. Coming out of the Navy I had four years coming to me, so I took three years at the University of Georgia and I took one year up in New York with the Society of Illustrators, and I would look for work. I went to New York to study under McNally. Ed Dodd, who drew Mark Trail, recommended that I take his classes. I would take them at night and look for work during the day. I had drawn up cartoon strips, and I went up there very excited and got deflated real quick. I was about ready to come back when I got work with EC/Mad. It wasn’t Mad then, but it was Bill Gaines’ EC.

WOODRING: Right. You say you studied fine art. Was that to help you as a cartoonist, or did you think you might want to be a fine artist?

DAVIS: I think it did, in a way. Because you look at the figure, the life figure, in different poses, and I took a lot of courses over again because I knew that I wouldn’t graduate with a degree and I had some good professors who would let me do that. So I took a lot of life classes, and they were quick poses. They weren’t something you would sit for an hour drawing a nude model or something. You would make quick sketches. I think that helped a good bit.

WOODRING: Were you still, at this point, absolutely certain that you wanted to be a cartoonist?

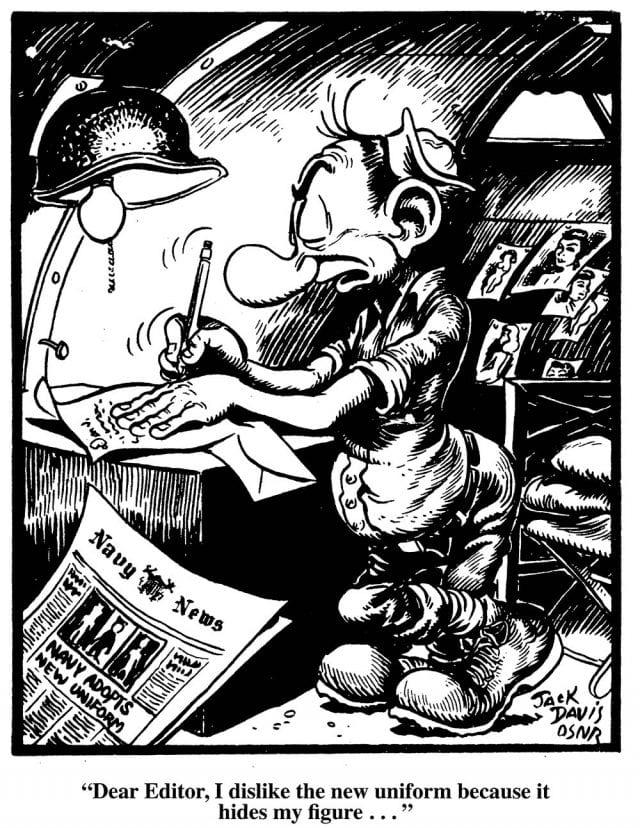

DAVIS: Oh sure. All my life as a little kid I wanted to be syndicated. I wanted to have my own strip, and that never, ever happened. And while I was in the Navy, I drew for the Navy News, which covered the Mariana Islands. And I had other jobs to do. I was a brig warden, I was with the fire department and with the master at arms — that was while I was on Guam — and drew a panel for the daily news. It flowed pretty well because I had a little guy, kind of like Sad Sack, a Half-Hitch that Hank Ketcham did…

WOODRING: Right.

DAVIS: I did that for about a year.

WOODRING: I’ve seen those Boondocker strips. They must have been hard to do.

DAVIS: I sent home every issue of the paper, and my dad had it all bound into one big hardbound book, and I still have it. I treasure it.

DAVIS: I pull it out and look it over and read where the Japanese were surrendering on Guam. So it’s good to look back on things like that. I looked back and there was Bill Mauldin’s stuff in the paper, too — Willie and Joe.

WOODRING: Neat. Then when you went to college after that, you sort of modified Boondocker into ... What was his name? Georgie?

DAVIS: Yeah. Like in the school paper. I took one little journalism course, but God, I couldn’t type. I was just not an academic student. I just loved to draw and have a good time. I was in a fraternity that was one of the best on campus, and it was a life of luxury in which I’d never had. I enjoyed that for three years.

Continued