He was the first star of French caricature's great age. From Gustave Doré to the Walt Disney studios, his zoomorphic cartoons have countless inheritors. From the 1930s through the 1950s, Surrealists worshipped him. But these days few remember J.J. Grandville (1803-1847).

The Paris show Grandville and Balzac hopes to change that. Mounted at the former home of Honoré de Balzac, it features some of the cartoonist's finest work. One of its rarities is a suite of prints which turned Balzac himself into a Grandville fan. This series, which is called Voyage pour l'éternité ("The Final Journey"), is a version of Holbein's Dance of Death. Although Balzac was knocked out by these prints, death really did seem to stalk their creator.

Grandville was born Jean-Ignace-Isidore Gérard, part of a family of artists in provincial Nancy. His grandparents acted under the stage name "Grandville" and his father painted portrait miniatures. It was assumed that Jean-Ignace would enter the arts. But the family also saw him as replacing a son – Adolphe – who had died three months earlier. This obligation weighed on the recipient, who felt it made him "the hostage of misfortune". Never allowed to use his own name, Jean-Ignace passed his whole life as Adolphe.

At 11, he discovered Le Nain jaune ("The Yellow Dwarf"), one of the first journals that came with a caricature. Sworn to oppose the censorious French government, Le Nain mocked its members as the "Order of Candle-Snuffers". In a sign of things to come for French cartooning, its editor was prosecuted, challenged to duels, jailed and – before giving up – forced to publish out of Belgium.

The French were fervent converts to English caricature and big fans of Gillray, Cruickshank and Rowlandson. Adolphe Gérard loved them too and he collected their prints. But the youth was equally impressed with a hometown figure. He was the medieval pioneer Jacques Callot (1592 – 1635), a master famous for his grotesques. Callot's most important work – and Grandville's favourite – was the stark and Goya-like series "Miseries of War".

Adolphe dreamed about such a series of his own. But, while he helped his father paint, his art took a different turn: that of turning people into animal figures. This was not an original idea but, from the outset, his take was striking. When giving human bodies the heads of birds or beasts, Adolphe paid careful attention to details. What made the gimmick work were his observations; he seemed able to detect the beast in anyone.

In 1825, this would-be artist moved to Paris. Here the entertainment centres – theatres, dance halls and cafés – were always crowded, like the narrow streets. Walking anywhere meant rubbing shoulders with scissor sharpeners, laundry carriers, rag merchants, chimney cleaners, coffee sellers, flower vendors and barbers. All worked side-by-side with the truly poor, who sold scraps of goods or old cigar butts. Early risers paid reveillers to wake them up and restaurants hired "guardian angels" who would see home drunks. All of this appears in Grandville's sketchbooks, with notes like "Legless man on the Pont des Arts" or "Twenty-three different types of gentleman's pipe". Often, he categorized his observations by their age, type and neighbourhood.

The Paris streets were also full of young girls in a hurry.[1] These were the grisettes, the force which made (and delivered) women's clothing. Grisettes were young and poor but said to enjoy a good time. They became heroines for the new, Romantic artists.

All this action created an idea, a view of the capital's communal life as something "modern". Artists from Balzac to Baudelaire explored this. But it was also ripe for capture in cartoons and it was this world that crystallized French caricature.

Adolphe Gérard had arrived knowing no one. But one of his cousins worked at the Théâtre de l'Opéra Comique – a perfect perch from which to observe. Haunting its lobbies and corridors, Adolphe filled his sketchbooks. The results soon brought him illustration work, but that failed to appeal. Something else had grabbed him: the emerging use of lithography. This process had changed making prints from a laborious job into something that seemed almost impromptu.

Rather than create on metal plates via incisions (like an engraver) or use acid (like an etcher), a lithographic artist drew directly on the stone. The crayon he used could break fairly easily, so his touch had to be light. Because lithography offered more subtleties, it attracted many a young, Romantic artist. But the first to exploit it for caricatures was a portrait painter in his sixties. Louis-Léopold Boilly – for whom Robespierre had sat – had a mammoth hit with his Recueil de grimaces ("Collection of Funny Faces"). His series ran from 1823 to 1828.

Adolphe Gérard took time to become "J.J. Grandville". After initial success as "I. Adolphe Grandville", this name was less a decision than an error – a printer misread his writing. But I. Adolphe Grandville was already established. His friend Gabriel Falempin had found him lodging near the École des Beaux-Arts. Although this was a tiny room five floors up, Grandville's eyrie became an artists' rendezvous. The painter Paul Delaroche lived next door and other pals included a landscape artist, a miniaturist, several writers, a comic singer and the artist-lithographer Eugène Forest. The neighbor whose acquaintance would prove most decisive was a 28-year old by the name of Charles Philipon.

The group dined in cheap eateries and spent many evenings together. "If we had money," said Alexandre Dumas, "we had beer. If not, we were happy just to smoke, joke and argue." The action always centered on a table covered in papers, pens and ink.

What was the host of such soirées like? Grandville was short, soft-spoken, skinny and shy. He sported a brown mustache, a goatee and longish hair – topped by a bald spot he carefully hid in his self-portraits. Friends like Dumas relished his wit but it hid a melancholy character and he was very competitive. Grandville liked to visit parks, printers' workshops and the theatre. But what he did almost all the time was draw. As the years went on, said a friend, "He never went out, never took time off for a walk or even a break."

By 1828, Grandville had drawn 72 lithographs. They included the sets Les Dimanches d'un bourgeois de Paris ("Sundays of the Bourgeois Parisian") and Chaque âge à ses plaisirs ("Every Age Has Its Pleasures"). Series such as these, conceived as collections, appeared in installments known as livraisons. Grandville's had run-of-the-mill subjects like dinner parties, in which funny pets mirrored their misbehaving owners. It was a touch he had stolen from Hogarth and Gillray.

Not unlike the gatherings in Grandville's studio, lithography's world was collegial and collaborative. All of its artists depended on lithographic printers – imprimeurs lithographes. As Patricia Mainardi details, there were different roles, with "creative artists … who drew original designs [but also] those who served as intermediaries, translating the drawings of others as engravers had always done". But many, including Grandville's partners Eugène Forest and Auguste Desperet were not just artist-lithographers (dessinateurs-lithographes). They were also artists or caricaturists in their own right.

Grandville almost never engraved his own drawings. Nor, after 1831, did he draw directly onto stone. He was severe with everyone who helped him and sometimes spoke of collaboration as a "torture". But he always saw his engravers as equals.

In 1828, the artist made his first mark with a series called Les Metamorphoses du jour ("Transformations of the Day"). Again, they were everyday scenes – but all their human protagonists had animal heads. The series was an instant hit, with Grandville's art appearing in every bourgeois home and every bookstore window. The Metamorphoses turned him into a household name.

Speaking animals had been around since Aesop. But, as publisher Charles Blanc noted, "No one before had dressed animals in our clothes, introduced them into our salons in heels or given them roles in the ongoing vaudeville of our world." From his elephantine bourgeois to a vulture with his rent book, Grandville's hybrid figures were fresh and entertaining.

In graphic terms, they were also ground-breaking. As the artist's biographer Annie Renonciat writes, "By making a metaphor into an actual metamorphosis, Grandville showed both the idea and its inspiration... His menagerie rapidly spread through Europe and soon suffused the collective imagination. He had created archetypes for generations of illustrators, cartoonists and advertisers."

Such metamorphoses were also literal, for all of them began as detailed scenes with actual humans. As Grandville's archives in Nancy demonstrate, he evolved his hybrid creatures through sequential drawings. Sometimes, it was only in the final drawing that hominid features gave way to those of animals.

At age 26, Grandville was a celebrity. But instead of repeating his hit formula, he followed it up with Voyage pour l'éternité. This perverse "funeral album", as he called it, demonstrates two things. One was his obsession with ideas of mortality. But the other is his special lithographic process. Whereas most artists prized the crayon for its nuance, Grandville scorned it altogether. He preferred a harder pencil or a pen and used both for lines so deep their points got stuck in the paper or stone. Says Renonciat: "His line was accusatory; it underscored and denounced."

Grandville replaced subtleties with color. Color prints of the era were always tinted by hand and all of the work was done by women. Such colorists had ateliers of their own, where their labors were guided by an artist's notes. Using gouache and aquarelle in five key colors, an experienced worker made 500 "passes" an hour. In addition to purifying his line, Grandville used simple colors – but he spiced them up with unexpected touches. In one Voyage print, for instance, Death is a waiter bearing a plate of mushrooms. His fungi sport a few red dots, to indicate their poisonous "red caps".

Whereas Metamorphoses tickled a funny bone, Voyage pour l'éternité struck a nerve. Balzac, one of few to find it hilarious, hailed the series with a rave: "Philosophical depth and caricature come wedded like this only in France and only in Paris. Having already having made men foolish and animals soulful, now Monsieur Grandville has made death gay."

For most Parisians, however, death was far from droll. Their city morgue sat right in the capital's heart and its anonymous dead were on show to the public (this was in hopes the bodies might be recognized). Corpses were arrayed on slabs and tilted towards the viewers, who were protected from the smell by thick glass windows. Visits to the morgue were popular and featured in guidebooks. "We go to see the drowned," wrote Léon Gozlan, "like people elsewhere follow the latest fashions."

Death also shaped Grandville's life more directly. After a year in Paris, he had sixteen friends. But within five years, thirteen of them were dead. In March of 1832, cholera swept the city, causing hundreds of fatalities in days. Over the next six months, almost 19,000 Parisians perished. The epidemic followed losses from that Revolution which erupted in July of 1830.[2] During its Trois Glorieuses or "Three Glorious Days", Grandville – like Dumas and Daumier – traded his pen for pistols.

The July Revolution secured press freedom and this changed Grandville's life profoundly. Balzac's endorsement of Voyage pour l'étérnité had appeared in a weekly called La Silhouette: like Le Nain jaune, a journal with caricatures. Grandville's friend Philipon was part of its management and, in November 1830, he launched a journal of his own. He called it La Caricature and Grandville drew its logo.

As the years progressed, Romanticism gained ground. But under Louis-Philippe, its new "citizen king", mainstream art was judged by its realism. This official art world was ruled by academic juries, patrons and prizes. If conventional artists didn't play the game, they failed. More progressive artists looked for refuge in the past and the medieval age became their great inspiration.

Not so caricature. Under a parade of kings, revolutions and Napoleon, censors had tried ceaselessly to kill it. Yet, whether using coded symbols or printing illegally, caricature had refused to disappear. After 1830, with more protections, caricaturists took aim at Louis-Philippe – directly. For five years, Philipon's La Caricature waged all-out war against him.

Grandville led the way. His formula, as Edwin DeTurck Bechtel later wrote , "was intricate and elaborate, involving many subjects, symbols, processions and groups of bureaucrats. The seven double-sized lithographs of his Grande Croisade contre la Liberté ("The Great Crusade Against Liberty") filled seven issues of the journal with its detailed and long-sustained tirade against Louis-Philippe and the government." Such multi-part pieces often ran for weeks. Subscribers to La Caricature (or collectors who bought the prints) assembled their pieces into a single work.

One such piece appears in the show: La Chasse à la Liberté ("The Hunters in Pursuit of Liberty"). Its specific targets and jokes are now obscure. But everything about it still looks modern, from its final, concertina form to the spot color (blood red) used for the letters that spell out "LIBERTY".

La Caricature's attacks hardly passed unnoticed: condemnations, seizures and fines were its way of life. In 1831, Philipon went on trial for "abuse against the King's person". It was his twelfth prosecution and made cartooning history. As he sketched Louis Philippe's head morphing into a pear, the editor posed a question: What constitutes resemblance? Who, he followed up, could "own" such a thing? Although attendees at the trial were amused, Philipon received thirteen months in prison. It would take seventeen years, but the editor's pear destroyed Louis-Philippe.

Militants like Philipon and Grandville were celebrities. Yet they had no physical protection. Their occupations were regarded as lowly and the artists survived project to project. By the early 1840s, Grandville could command more than twice the fee of most La Caricature contributors. Yet he never felt financially secure. Between 1830 and 1835, a job at La Caricature was also actually dangerous. Reviewing the paper's files over a century later, Edwin Bechtel was shocked at the level and seriousness of the attacks its personnel suffered.

Radical journals such as the Corsaire, Tribune, Réformateur, Bon Sens and Populaire were also targets. In over one hundred prosecutions, for instance, the Tribune received twenty convictions and a total of forty-nine years in prison. For calling Louis- Philippe's Chamber of Peers "prostituted", publisher Ferdinand Bascans spent three years inside.

Grandville was their acknowledged "King Of Caricature". As such, he became the backbone of Philipon's L'Association Mensuelle lithographique (August 1832 – August 1834). This was a kind of private subscription club whose members paid for exclusive luxury prints. The money the scheme raised helped defray fines and court costs. But, well before the Association, Grandville incurred his own problems with the law. The worst of these followed two of his best-selling prints.

The first was entitled L'Ordre règne à Warsaw ("Order Prevails in Warsaw") and it was published on September 20, 1831. The drawing's title quoted Louis-Philippe's Foreign Minister hailing a notorious bloodbath of the Polish-Russian War. This had ended a Polish bid for independence partly inspired by the July Revolution. Because the Poles' rebellion had support in Paris, the French king's opposition of it caused local riots. These were brutally quelled by Parisian police. On September 25, 1831, Grandville portrayed this, too, in a print called L'Ordre public règne aussi à Paris ("Order Also Prevails in Paris").

Both depict cruel officers with disdain for their "foes". In Grandville's Polish print, one has severed a head. In its French companion work, a policeman wipes blood from his sword. This pair of prints flew off the shelves and, three months later, both were still on sale.

The consequences were immediate. Coming home one night, Grandville was mugged in his own building. A crew of thuggish policemen had lain in wait and the artist was saved only by Gabriel Falempin. His neighbour owned a pair of pistols, with which – while haranguing them – he succeeded in running off the gang.

Grandville refused to be intimidated. Instead, he replied with a print called Oh!! Les vilaines mouches!! ("Oh!! These nasty flies!!"). It shows him at the studio window, confronting a swarm of wasp-like flying policemen. While they have stinger-like swords, he has just a pencil. Grandville signed this print "Victor Larangé" which, phonetically, means "Victor the Spider". He also filed criminal charges alleging his home had been invaded.

But, on July 28, 1835, there was a dramatic attempt to kill Louis Philippe. Although the King escaped, forty people died and many others were injured. The government enacted immediate legislation that give the courts and censors full control. They also established new press offenses, which forbade mockery of the King, critiques of the government, use of the term "Republican" and any expression of hope that the monarchy end. All reporting of press trials was totally banned. Worst of all: no drawing, lithograph or engraving could be sold (or shown) without state approval.

Philipon was forced to close La Caricature and he saved Le Charivari only by switching its targets. Political cartooning gave way to social satire.

By this time, Honoré Daumier was La Caricature's principal star. Grandville, always ambitious, had switched his attention more to other publications. But – was he secretly happy about the censorship? Had all the physical dangers worn him down? One Grandville scholar, Clive F. Getty, thinks so. His idea is based on a journal note from April 20, 1833. Upon returning home from a walk with Daumier, wrote Grandville, "Ideas from the past again returned to upset me – misery and fears. philippon (sic) comes by to get me and we go to the print works … fresh worry – At the lithographer's, disgust with what I do – Fears… Once again, my spirits sink".

Oh!! Les vilaines mouches!! is not the work of a frightened man. But three months after Grandville made his April entry, he became a family man – marrying his cousin Marguerite Henriette Fischer. Pretty and devoted, Henriette soon dominated Adolphe's world.[3] Adolphe and Henriette moved to a small apartment near his studio; they also rented a house in the suburbs. They had three sons adored by the artist: Ferdinand in 1834, Henri in 1838 and Georges in 1842.

In 1836, Grandville started to illustrate books. It was another new field in which, again, his rise was swift. But book illustration opposed French authors and artists. Their disagreements stemmed from yet another novel technology: end-cut wood engraving. These engravings functioned like typographical blocks and permitted illustrations to appear on the page with text. Married to the also-new, steam-powered printing press, they substantially reduced production costs. Imagery got better, illustration snowballed and it all cost producers much less.

To master such end-cut wood work, Grandville changed his style. He made it even more refined, more precise and more exact. His first important book commission, in 1838, was La Fontaine's highly prestigious Fables. This was a great success and Grandville went on to tackle new books every year.

French book distribution first used the old livraison model. More like a modern comic series, these illustrated works were assembled only once a story finished. Such staggered distribution let producers fund more illustrations and tailor production to the level of sales. But, as illustrated books became more popular, novelists like Flaubert and Victor Hugo felt threatened. Many of them wrote for illustrated compilations such as 1840's best-selling Les Français paints par eux-mêmes ("The French As Seen by Themselves"). But, as more and more texts were interspersed with pictures, anger spread among eminent authors. They knew many of these illustrators were celebrities – and, now, they were invading the word's most sacred precinct. Calling it cheap, shoddy and "industrial", novelists raged against the illustrated book.[4]

Assertive artists like Grandville, however, saw opportunity. With the young editor Pierre-Jules Hetzel, he sought a showcase for his zoomorphic trademarks. The pair came up with it under the title Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux ("Scenes From the Private and Public Lives of the Animals"). By giving them a list of animals and letting them write as they liked, Hetzel bought in content from literary stars. The results ranged from "A Philosophical Rat" to "The History of a White Blackbird". Yet Grandville pulled it all together using two schemes: 'types' and 'scenes'. His types, individual portraits, focus on the bestial in man; the group 'scenes' have animals engaged in human actions.

Grandville's animal comedy was also a swipe at Balzac's 1830 Scènes de la vie privée. Like the artist's Metamophoses, it had bumper sales – which infuriated Grandville's early fan. As Keri Yousif notes in Contesting the Page, "Given the population of Paris in 1841… just under one million with an estimated audience of readers at almost 300,000, Grandville reached an extraordinary level of saturation… selling 25,000 copies. Balzac's novels, on the other hand, had initial first-edition print runs ranging from 1,200 to 3,000." The results were reflected in their incomes. Neither was a millionaire – but, under a pseudonym, Balzac was dodging his creditors.

In a letter to his mistress, Balzac railed about "those stupid works like La vie privée et publique des animaux, which sell 25,000 copies just because of their illustrations". He was still angry over a year later, writing, "It's all about pleasing that greediest of organs… the one whose demands have become limitless… the Parisian eye! That eye consumes… twenty illustrated works a year, a thousand caricatures and ten thousand illustrations, lithographs and engravings."

Then, as now, images had unsettled society.

Grandville's own life, though, was far from easy. Ever since the birth of her first son Ferdinand, Henriette's health had been very poor. In 1838, the year Henri was born, Ferdinand developed meningitis and died. By 1841, Grandville was confiding to Hetzel that his wife suffered "constant pains, a general malaise and internal troubles". Not long after this, at a family dinner, three-year-old Henri choked to death on a piece of bread. "Nothing can ever console me," Grandville told Hetzel – with whom he was still at work on La vie publique et privée des animaux. He had busts of the dead children made for his bedroom.

When Henri died, Henriette was pregnant with Georges. Although he was safely born two months later, his 32 year-old mother failed to survive. Grandville nursed her desperately, trying to hold on by drawing her. Henriette died five days after their anniversary.

Always a compulsive worker, Grandville now struggled. The project he needed to finish was Emile Fourgues' comical Les Petites Misères de la vie humaine ("The Small Miseries of Human Life"). The artist wrote his former father-in-law that he lacked "the cold blood I need to keep on drawing funny scenes". But, when Les Petites Misères was finally published, his illustrations won praise for their wit and vitality.

Constantly worried about the health of baby Georges, Grandville remarried less than two years later. He wed a twenty-four-year-old, Catherine Marceline Lhuillier. Like both Henriette and Adolphe, Céline came from Nancy.

Grandville was now creating a book of his own. He wanted the two volumes of Un Autre Monde ("Another World") to be his masterpiece – his definitive critique of the age.[5] Still his best-known work, Un Autre Monde's actual title is Un Autre Monde: transformations, visions, incarnations, ascensions, locomotions, explorations, pérégrinations, excursions, stations, cosmogonies, fantasmagories, rêveries, folâtreries, facéties, lubies, métamorphoses, zoomorphoses, lithomorphoses, métempsycoses, apothéoses et autres choses ("Another World: Transformations, Visions, Incarnations, Ascents, Locomotions, Explorations, Peregrinations, Excursions, Stations, Cosmogonies, Phantasmagoria, Reveries, Frolics, Jokes, Fancies, Metamorphoses, Zoomorphoses, Lithomorphoses, Metempsychoses, Apotheoses and other things").

The book takes place in a parallel world whose events are relayed by the characters "Dr. Puff", "Krackq" and "Hablle". This trio's adventures, episodic rather than narrative, unreel more like a graphic novel than a book. "In Another World," writes Patricia Mainardi, "Grandville is thinking in pictures with the kind of free association characteristic of the dream state, of Surrealism… [and] of later experimental literature."

It's easy to see why the Surrealists loved it and in fact Un Autre Monde has dated less than much of their work. In the chapter Une Revolution Végétale ("Revolution in the Plant World"), for example, flowers and vegetables plot their rebellion. Since "only those with nothing to lose endorse such change", leadership of this mutiny falls to a humble thistle. But he successfully rallies a chlorophyll charge: "And you vegetables, such an industrious and fertile people… Will you suffer your children to be torn away at the tenderest age?… Hear their cries as they call for vengeance from the frying pan!".

No one definition can describe Un Autre Monde. It's not really a book, nor a set of caricatures, nor does it really have a coherent storyline. But it did more than pioneer Surrealism; Un Autre Monde reconciled image and text. As the art historian James Cuno explains, "Classical book design kept the image within clearly defined borders or, sometimes, shunted off to a separate page. Romantic book illustration, on the other hand, challenged the distinction between image and text and sought a full integration of the two.… This is indeed Grandville's achievement in Un Autre Monde…the reason it is generally considered his masterpiece and among the most important and influential works of Romantic art." [6]

Grandville fretted about Un Autre Monde's reception. He was right to do so; the book was an utter failure. Its second volume was abandoned and the artist returned to his signature metamorphoses. In 1846, his enchanting Les fleurs animées ("Flowers Personified"), won him a new – and largely female – following.

By then Grandville once again had a family. Georges was four when, in 1845, Céline gave birth to a fourth son they called Armand. "For the first time in my life," exulted the ecstatic father, "I can allow myself to live in the present." Once again, he rented a house in the country for his brood. But the truce with death was brief: in 1847, Georges fell ill and died.

In a letter to his publisher, the artist was bitter. "Never have I demanded fate spare me. But I would have begged it not to strike the way it has, never holding back, never even pausing... Death has taken time out only to sharpen his scythe." Yet again, he tried to find some solace in his work. He urged Fournier to visit, "whenever you can, whenever you like", so the pair could develop another project.

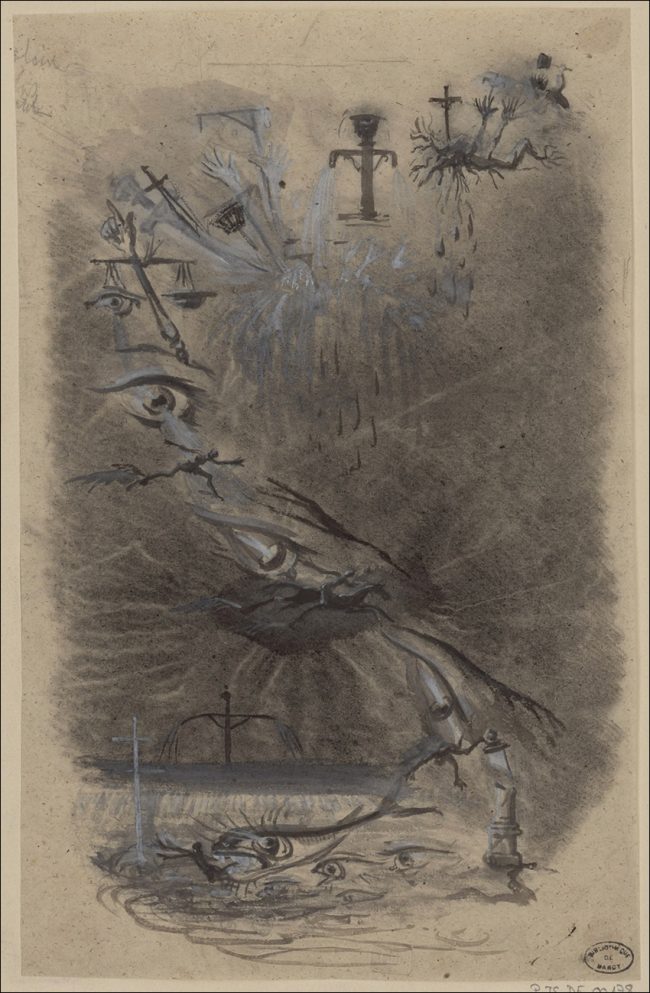

It was not to be. When an eye inflammation kept him from drawing, Grandville sank deeper and deeper into gloom. His eyes recovered long enough for him to send Le magasin pittoresque two strange drawings, literal transcriptions of dreams with written explanations. The first, Crime and Expiation, shows bleeding branches, groping hands and staring eyeballs. Yet, as Grandville suggested in his notes, "It may interest those who nurse their own imaginations".

Twelve days after writing that, he was dead.

On March 1, 1847, he went to bed with a bad sore throat. Over the week, this condition (probably diphtheria) worsened. He became delirious and, when his ravings grew violent, Grandville was taken to the8 Maison de Santé in Vanves. This was the facility of two pioneering psychiatrists, Felix Voisin and Jean-Pierre Falret. Both were noted progressives who lived on the premises, where they carefully supervised each case. All their patients got 24-hour care and their families were encouraged to visit.

Grandville's stay, however, proved brief. On March 17, 1847, after three days and nights of misery, he died. The artist had composed his own epitaph:

"Here lies J. J. Grandville.

He could bring anything to life and, like God, he made it live, talk and walk.

Only one thing eluded him: how to live a life of his own."[7]

Dying as Romanticism reached its peak didn't help Grandville. But many things have combined to paint him as an artiste maudit. One of these was the tone of his own colleagues' eulogies. As Annie Renonciat says, "All of them underscore the absurdity and craziness of his ideas… They cite things like 'a verve that was all too lively' or dreams and fantasies they describe 'far too fleeting, too whimsical'." Vanves' Dr. Falret, who was the first to analyse bipolar depression, might have had a very different view of such traits.

A decade later, Charles Baudelaire – who detested Grandville's work – added a coup de grâce. "There are superficial people Grandville entertains," wrote the poet, "but… he frightens me." It remained only for Surrealism to assert, and then celebrate, his attraction to the irrational.

No-one bothered with the artist's wife Céline, who was at his side through the final years and days. With exactitude, she related Grandville's end to Armand. Then she made him swear never to believe "those who so distort how your father died."

These days anyone can draw a screaming vegetable. No one's going to say it means they're crazy. Yet the parallels between Grandville's age and ours – the faux-democracy, the new technologies and pervasive commercialism – are certainly striking. Grandville, however, proves that art can fight. Plus, when speaking truth to power, he remembered to laugh.

- Grandville et Balzac, Une Fantasie Mordante (Grandville and Balzac, Fantasy That Bites) runs at Paris' Maison de Balzac through January 13, 2020