After 30 issues of time-traveling action, 2019 saw the conclusion of Cliff Chiang & Brian K. Vaughan's Paper Girls series. I spoke with them a few days before the final issue arrived in stores, which was also a few days after Amazon announced they would be adapting the series into a television show for their Prime service. While my interest in Paper Girls originally stemmed from my ongoing admiration for Chiang's work, especially with colorist Matt Wilson, I found I came to love Vaughan’s demanding and at times unusual (for him) style of writing. There are few contemporary writers in comics that have had as much influence as Brian K. Vaughan, both in terms of his embrace of accelerated cliffhanger dependent storytelling that now dominates television and franchise filmmaking as well as the way in which he has handled his career—the usage of Marvel, DC & Vertigo work to build a name recognition that would sustain the work he’s done at Image and Panel Syndicate. While others have followed (or attempted to follow) this same track, Vaughan’s success with Saga is, for an entire generation of comics hopefuls, the only career model they care about. But with Paper Girls, a different Vaughan seemed to be in play—one who was grappling with the cringe-ier aspects of nostalgia based genre work, the complexities required for generations to get along with one another and the ever-present malaise of middle aged ennui. All of this was at play in a series that was also packed with action and subdued romance and focused on children—girls, at that, with nary a female creator involved. As someone who has moved away from reading most non-Ennis related single issue comics over the last few years, Paper Girls was a pleasure to keep up with, but one that I always felt like had more beneath its more obvious, mech and Chiang based pleasures.

This interview was transcribed by Sora Hong & Jasmin Davis, with additional copy-editing by Alec Berry.

Tucker Stone: Correct me if I’m wrong, but neither of you have done extensive interviews for Paper Girls. Is that right?

Brian K. Vaughan: The least number of interviews we can get away with is always the goal. No offense. [Laughter]

Cliff Chiang: Most of them happened with the launch of the book, then with the start of the second arc. We haven’t really done many since then. Maybe one more?

Why is that?

Vaughan: I won’t speak for Cliff, but I’m just happiest letting the work speak for itself, first and foremost. I find I am such an ill-suited advocate for my own work. I’m terrible at describing it, and it’s hard to do. Secondly, interviews just don’t feel like a useful promotion tool. I read something because two or three of my friends recommend it to me.

I just miss Cliff [Cliff laughs], so this is a nice opportunity to get a postmortem on the book that we talked about very little [publicly].

Chiang: I think it’s hard to promote a book when you can’t really talk about it. I mean, before it’s come out. Those answers end up being a little bit too PR-speak. I’d much rather talk about the work itself and why people might find it interesting, or if they have questions about choices that we made, as opposed to this theoretical version that we’re trying to sell you.

Vaughan: I think for an ongoing comic series 99% of your publicity work is having a great first issue. Most people, if they read a great first issue and they love it, and you can sustain that … that’s so much more important than having a strong social media presence. I find that stuff barely moves the needle.

I’m probably giving us way too much credit by saying that. I think it’s just a testament to the compelling world Cliff creates in that first issue. I don’t know that it’s [strictly] name recognition. I also don’t put too much stock in that. I think you’re only as good as your most recent work and that doesn’t buy you too much loyalty from readers, after a point. I don’t know, Cliff, am I just working too hard to justify our laziness for not doing more press?

Chiang: [Laughs] I don’t know. I think maybe the two of us are just not built that way. I think there are people who can absolutely take advantage of social media and pimp the shit out of something, but I think that comes at a cost. That ends up becoming its own job, and both of us, I think, would much rather focus on making comics.

Brian, you have a real hands-off relationship with social media, right?

Vaughan: Well, now that Saga is on a break, I’m dipping my toe in the Instagram waters. It’s okay. I’ve just always liked that Saga and Paper Girls were my primary ways to communicate with readers. For the most part, like Cliff said, whenever it would come up, “Do you want to do an interview?” and it’s like “Oh my god, we’re putting out a monthly comic,” it is just so — to do that, and to inevitably have another job on top of it, and to have a family … there’s no time.

Life’s too short.

Vaughan: I suppose.

How did Paper Girls come together? This isn’t the first project you guys had considered, is it?

Vaughan: I don’t think we got too much farther in terms of an idea than Paper Girls. Cliff?

Chiang: Not really. It was always dancing around as something that might happen or could happen. This is the first actual pitch I ever really saw from Brian, and the first that we talked about in depth.

Vaughan: Cliff drew one of my first projects for Vertigo, and it was just so incredible out of the gate. I mean, he was clearly so talented and elevated the script, and he taught me a lot, and I was desperate to work with him again. But it just took us years before our schedules aligned and we finally had a moment.

Chiang: Yeah, and Brian was so good at keeping in touch, even though we hadn’t worked on anything. Even though we’d only worked on that one job, which kind of happened by accident. I think there’s something about persistence, about being able to read someone else’s work and realize how compatible you might be.

What was the timing of the Vertigo story?

Vaughan: I had just been hired to write the ill-fated revamp of Swamp Thing starring Swamp Thing’s daughter —

Abby Arcane? [Laughs]

Vaughan: Tefé is the daughter’s name.

Tefé, okay! I shouldn’t have tried.

Tefé, okay! I shouldn’t have tried.

Vaughan: Oh man, the accent over the ‘e’ in her first name was always a real struggle for our letterers. [Laughter]

Yeah, so, I worked on that, and before that series came out, which would’ve been like ’99 or 2000, there was a Secret Files, or was it the Winter Special? What the hell was it for?

Chiang: It was Swamp Thing: Secret Files. I think it was maybe a few issues into the run, maybe after about six issues had come out, and they were trying to get more eyeballs on [the main series]. They had this Swamp Thing: Secret Files that had everything Swamp Thing. It had Tefé. It had John Constantine. It had all sorts of stuff.

Vaughan: I’d been fortunate enough to work with way better artists than I deserved by that point, but Cliff just blew everyone else out of the water in terms of what he was doing, where he was placing his camera and how he was using panel sizes to tell a story. It was elegant and seemingly effortless. It was the kind of storytelling that I was trying to do and failing at, up until that point. Seeing his pages for that story was a real turning point for me. So, I stalked Cliff for years! It’s embarrassing. [Laughter] It’s few and far between that you work with an artist who you just have that sort of rapport with.

Chiang: That was probably one of the first two or three published jobs I had at Vertigo. I hadn’t worked on very much. A friend who was working on that story, [who was originally slated to be the story’s artist], had a full-time job in animation, and she fell behind, so I was helping her with layouts. When it finally became too late for her to actually draw it, the job came to me because I had basically thumbnailed the entire story and had a two week lead on anyone else who might take over. So, I managed to just kind of sneak into that story, and it was very easy to draw. There’s a pacing to Brian’s stuff that is cinematic and very natural to me, so it was a lot easier than I expected. It was all there, so I didn’t have to spend energy trying to fix things when I could just focus on the characters and the emotion and just draw the scene the way Brian had laid it out, trying to just do my best to keep it visually interesting and moving and do it justice.

I mean, I was putting a lot of thought into compositions and staging and stuff like that, but the pacing of it felt very much like the way I’d want to pace something that I wrote myself, so I knew it was a good partnership. But nothing materialized after that! [Laughs]

Now that you’ve worked with Cliff for all these issues, obviously you’re going write for him differently than you would have when you started out. You kind of know what he’s going to fill in. You know where his strengths are. But what changed over time? Do you have a sense of that, or is it something organic?

Vaughan: Oh yeah. No, definitely. I mean, at the time, I never had the luxury of having input on who my artistic collaborator would be, so I would just write in a generic style for anyone, but it was definitely over-describing and just trying to protect [the story], I think. And I remember hearing about him, like, “Oh, shit.” I imagined no one wanted to draw my story, so they had to get this Jimmy Olsen cub editor from inside. It’s like, “An editor is drawing my … ? This is going to be a disaster.” And it was so excellent! Cliff was so Cliff right out of the gate.

It was so good you didn’t call him for 15 years. [Laughter]

Vaughan: When I called him, Cliff was rightly too busy working with other incredible collaborators! I think it was back [when he was working] with [Brian] Azzarello. I was just salivating. It would be imaginative and so clean. He was just getting better, and each project he would kind of reinvent himself. I just wanted to win that game of musical chairs, to be waiting there when he had an opening.

Cliff, the way I remember it is, when you first started talking about Paper Girls you were also talking about that Batman whatever it was … Pulp Batman? Batman with guns? Batman but with guns was still a live option at that point. It wasn’t already dead.

Chiang: No, that was long dead. They killed that right before Wonder Woman. It was supposed to come out of that DC pulp universe line called First Wave.

No, no, I remember that, but what was the other thing? There was another thing you were considering jumping ship to do. You were like, "it’s either going to be Batman with guns or it’s going be this other thing."

Chiang: Oh, Wonder Woman.

Oh, it was Wonder Woman. Okay. You think you made the right choice?

Chiang: [Laughs]

I’m always curious about Batman with guns. Do you remember Batman with guns, Brian?

Vaughan: I don’t, but I love the phrase “Batman with guns.”

It’s a good phrase. I'm going to keep repeating it. [Laughs]

How much of Paper Girls did you have before you went to Cliff?

Vaughan: Not a ton. I knew Saga was successful, and I felt like I had the creative capital to work with someone on something that was not commercial. It wouldn’t hope to be a film or anything. I had an idea for a while that involved 12-year-old newspaper delivery girls and time travel, and Cliff was always one of the first people I considered, but I think — Cliff, did you have that Robin story? Had that come out before or as we were talking about Paper Girls?

Chiang: It was around the same time.

Vaughan: I was definitely seeing how well Cliff draws young people. Even the best artists in comics usually make kids look like weird misshapen adults, but Cliff has a sense of the gangly strangeness of youth. I knew that we were from a similar generation, so it just felt like, “Oh, if I could get Cliff’s brain involved in this early, he would be perfect.”

Also, girls have different kinds of haircuts and nobody can draw hair, so it’s like you’re literally throwing kids, bicycles, vehicles, and hair, all of which are extremely complicated to draw …

Vaughan: You’re kidding, but it’s so true. [Laughs]

Cliff Chiang and Urasawa can do hair. That’s about it.

Chiang: All it needed were horses.

Vaughan: I was just going to say, I can’t believe we didn’t have … well, we could do a wild west sequel to Paper Girls!

Chiang: Yeehaw, Paper Girls. [Laughter]

It does seem like everybody has a time travel story, or a Dr. Strange story. You did Dr. Strange early on, though, so you got that out of the way.

Vaughan: Right, exactly. For the seasons I worked on Lost, time travel played a big part in the story, and I was obsessed with time travel as a kid, but I guess I wanted to take my crack at it and do something that was hopefully a little more subversive. But it was definitely born out of the fact that, yeah, I have young kids of my own, and they’re so over-protected. I’m just thinking back to my own relatively latch-key childhood, how strange that was. It just felt like being 12 in the 80s had a dramatic interest that we could exploit

Is there an editorial voice in Paper Girls?

Vaughan: Cliff was the only editorial voice on the book, in every sense of the word. There’s never been any discussion with Image. No one tells us anything.

When was the last time you had an editor?

Vaughan: Maybe the last issue of Ex Machina? But not since I’ve been at Image or Panel Syndicate. And I’ve worked with great editors, and I love them, but it’s just not something I’m interested in at this stage of my career.

This is not a criticism, but it’s a more complicated book, y’know?

Vaughan: It’s a weird one.

There’s a style to it that I can’t really place, where it reads like you guys have abbreviated emotional beats. The character Tiffany … she jumps on top of the flying motorcycle, and it explodes. It happens with such extremity and such abruptness. It’s something that I don’t think you can really do in television because you would require this build up. There’s a lot of that throughout Paper Girls. There’s a desire to skip through what I think are the expected structures in these kind of stories.

Vaughan: Definitely. Subverting the expected was something we wanted to do. Something Cliff and I talked about a lot is that full-page reveal of Mac where she uses a homophobic slur against another kid. It’s this moment that feels like a traditional superhero splash page, and we really wanted to undercut it as a reminder of the casual homophobia of the past. That’s something that’s been glossed over in a lot of this 80s nostalgia porn [prevalent today]. You can do things emotionally, as you’re saying, in comics that you can’t do in film or television. I definitely think Cliff is the master of eliciting emotions with just images, no words. So yeah, I think we tried to do that as often as possible.

Chiang: There’s just not a lot of fat on the book. It moves you so efficiently through the scenes, and it allows us to get as much story in as we can without dragging it out and potentially making it too sentimental or saccharine. So, in a way, it almost becomes documentary-ish, where it’s there for you to pick up on. If you get it, you get it. If you don’t, we’re just going to move on.

The strongest thing in Paper Girls, for me, is in the final issue. The pacing of it, the fat that is allowed, is the biggest subversion in the entire series. Maybe that’s because I’m middle-aged, and I have a small child and I like those moments, now? The ending seemed like you were describing bigger things that happen prior to that final issue, but was that always the idea?

Vaughan: For me, much more so than the penultimate issues, getting all the plot stuff off-stage … there’s a lot of that there in the beginning, and a lot of it grew organically. Spoiler alert, I guess: the kids riding off into the rising sun in the morning is what Cliff and I discussed a lot at the beginning, a kind of melancholy, bittersweet magical realism. With Saga, I wanted to do a book of how it feels to be a parent. Paper Girls is what it feels like to be 12 and the way 12 can feel like an eternity, and it’s over in an instant. You have these huge moments colliding with the mundane ones, but the mundane ones you remember more. I’ve just been trying to remember how it feels to be 12 as my kids approach that age, and as I rapidly get farther and farther away from it.

One thing that comes up over and over is the “young versus old” aspect, both in the time traveling elements but also in seeing these girls go against everybody. Where’s that venom come from?

Vaughan: [Laughs] Cliff, do you have venom for any other generations?

Cliff, you do. I’ve heard you before.

Chiang: [Laughs] Yeah, yeah. Sure. I think it’s just what Brian captured so well, especially in that last issue, but throughout it’s the idealism of these young kids. They haven’t been burned and hurt the way their adult counterparts have, so they’re innocent, and they still have very strong beliefs, and they want to stick to them while everyone else is compromised and broken. They’re fighting against that. And you need that. You need that kind of strength. Even if the old timers’ position might make more sense to me now — in an adventure, who do you want to root for?

Vaughan: I guess for me, it was thinking about our old timers. A very conservative group. Like, I did one group of time travelers like that, knowing that we must maintain the status quo at any cost, and then our futuristic teenagers are sort of this progressive side because they have the capability to change things we should. I like that our kids at 12 get to be brutal pragmatists because their ideals are more about friendship and taking care of each other. They’re not politically motivated. They exist outside of that. They’re about to enter that adult world. I like that push and pull, and that there are no bad guys in the story. The characters are just differing perspectives. I didn’t want to write, “shitty Millennials don’t know about this,” or like, “Generation Xers were so wise.” It’s all just a bunch of fucked up groups of fucked up people being thrust together and having to coexist.

Is this, in part, a reaction to the contemporary climate, the way that you do have two groups who want to have a very specific argument about the way American society should be structured, whereas there’s a younger group who doesn’t want to participate in those particular things and is more loyal to each other? I see that in Paper Girls, but I wonder if that’s something I’m putting on it, or if that’s something you thought about.

Vaughan: As you were saying that, I realized that I’m deeply influenced by my parents. My parents have always seemed to like growing older, and they have always liked the way the world was becoming better in ways that were imperceptible to me. “Make America Great Again” wasn’t even a thing when we started working on this book, but I guess I noticed a little bit of danger in people pining for the good old days, and I remember them as being mostly horrific. There’s very little I pine for from the 80s, even though it’s where so much of the creative energy that I’ve inherited came from. I just wanted to do a book that was skeptical of the past, present, and future.

The way the Parkland students reacted to their situation reminds me of the way the Paper Girls react to a situation, where instead of trying to play by a specific rule structure regarding how you deal with the shooting, how you deal with something political, they react with true, raw, real emotion: “This is awful and unacceptable. And we’re not going to talk about the logistics of why these things occur. We’re going to talk about the real root problem, which is, ‘This is wrong. People shouldn’t die this way. Our friends shouldn’t die this way. This shouldn’t happen in a school.’” And I appreciate that.

Vaughan: No, I get it, and I agree with you completely. I think that’s just a big part of being 12. Cliff and I talked before we started working on this, and we said we didn’t want to rely on movies from the eras Cliff pointed out, like a movie that came out in 1988 which was probably designed in 1984 or something. We went back and looked at a lot of our yearbooks and my mom sent me a creepy file on … She kept so much of the essays that I’d written from school. [Laughter] It was kind of terrifying. It’s also heartening to look back, just at 12. I think my classmates and I were way more serious and thoughtful than I had remembered. I only remember the dopey pop culture and idiotic things I did, but I think we forget, if not just how deeply kids feel, but how deeply they think. I think we just wanted to write characters to the top of their intelligence, and we hoped readers would respond to them.

Are you guys suspicious of the embrace of nostalgia? This kind of, like, 80s as reference porn?

Chiang: Yeah. Part of the goal, even though Paper Girls starts off in the 80s, was to present that almost as objectively as we could. We didn’t want to engage ourselves in too much nostalgia. There are references to things, but that’s just the way kids talk. We tried to present every era as objectively as we could, so there’s good things about it and there’s bad things about it. There’s a real danger in too much nostalgia, specifically for a time like the 80s, which had many cultural flashpoints that we are still dealing with.

Like what? When you say danger, what do you mean?

Chiang: We’re still dealing with political situations, both in terms of U.S. foreign policy — The first issue has the newspaper headline from ‘88, about the Iran-Iraq … What was it, the treaty? Brian, do you remember exactly?

Vaughan: Yeah. It’s all things that have continued throughout the decades since. They’re still there, yeah.

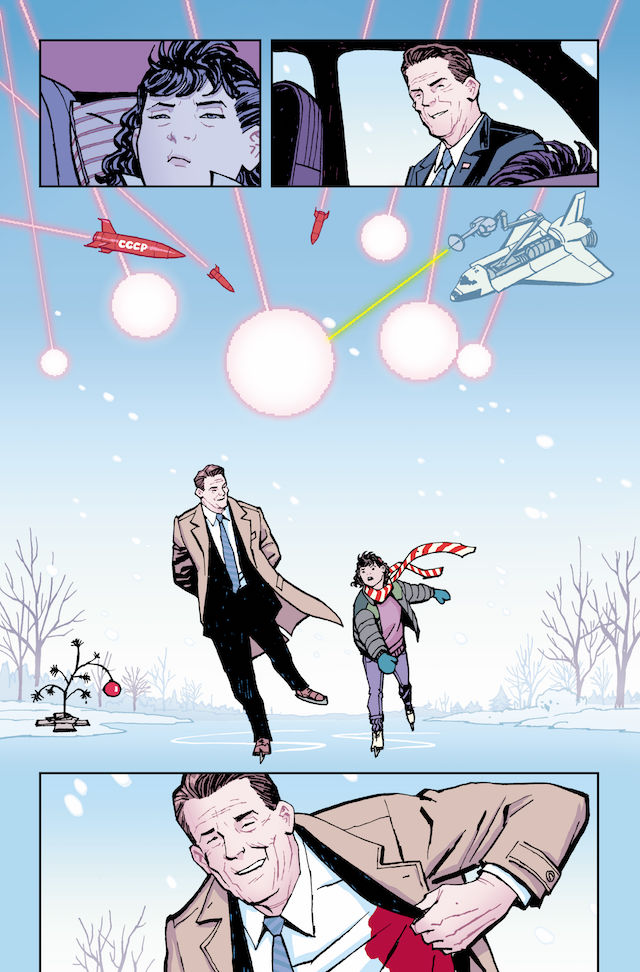

Chiang: And when you throw a real-life person, like Ronald Reagan, in there in a dream sequence, even though it’s kind of dumb, almost like a joke, there’s resonance to that. Then you talk about things like homophobia and AIDS and the consequences of things. So, there’s a way in which we can look back at the 80s and say we’ve come so far, but we haven’t come far enough.

Chiang: And when you throw a real-life person, like Ronald Reagan, in there in a dream sequence, even though it’s kind of dumb, almost like a joke, there’s resonance to that. Then you talk about things like homophobia and AIDS and the consequences of things. So, there’s a way in which we can look back at the 80s and say we’ve come so far, but we haven’t come far enough.

Vaughan: I’m similarly skeptical of nostalgia. I don’t know if skeptical is the right word, but I worry about being overly reliant on it. I always talk about how my dad had the Shadow and Tarzan. I got Spider-man and Star Wars, but it feels like my kids have Spider-man and Star Wars, too. Corporate interests are keeping these characters alive, sometimes past their relevancy. I guess it’s up to people to decide. But knowing that James Bond is never going to die because there’s a corporate need for there always to be a James Bond … that does hurt storytelling. It says we need to take a swing at something wholly new that’s engaged with the moment and isn’t concerned about being a franchise or living forever. Nostalgia is comforting, but I do think it can hurt relevant artwork.

Well, it’s oppressive. It’s conservative. It makes it a lot easier to fill up a library or bookstore if you can rely on one giant corporation to provide the same stories to fill the need. Ultimately, one of the more subversive elements of Paper Girls is that it doesn’t lend itself to IP. It doesn’t lend itself to a lot of merchandising.

Vaughan: We’ll see about that!

Well, yeah. Everybody’s going to do the deal.

Vaughan: Absolutely. There wasn’t too much thinking about lunchboxes or action figures when we began it. But definitely TV. I, like you, haven’t watched Stranger Things yet because I didn’t want to be influenced, but you have to give those people credit for… I thought this was the kind of thing that could never be a TV show. It’s got prepubescent protagonists in adult situations, and Hollywood has traditionally had such aversion to doing that, so they definitely made it safe again for those of us who were weaned on Stand by Me [or other] movies that blazed those trails first.

We’re talking about engaging with your suspicion and concerns about nostalgia, about consumerism. But what drives you with something like Paper Girls?

Vaughan: Cliff, do you have a snap judgement for what drives you? Cliff’s calendar is what drives him. [Laughter]

When we started this project, I’d originally talked about 25 issues, and Cliff was wisely like, “Oh, yeah. I see how we need to book end it. Each girl will have their own arc to be spotlighted, but then we need this.” By the time I got home from New York, I literally had the next four years of my life. Cliff had set things out down to the day, and we never deviated from that. Cliff was obsessive compulsive from the get-go. I like that. I like having that, “Don’t just write when the muse strikes you. You need to be writing right now because Cliff’s calendar demands it.” I like having an outlet to say whatever is scaring me about my children and my past and my present, and it can be poured into an issue. It’s like all my books. What drives it is whatever I’m afraid and confused about. It’s just an ongoing thing with me.

And if you lose it, you put it in the book, and it goes away. You put it away and you’re sealing it in? [Laughter]

Vaughan: Yeah, I’m healed. No! [Laughter] Rarely. It feels like getting drunk in reverse, where it’s just a long painful hangover that you have to endure, and then getting it out feels very good. Or it doesn’t feel good, I should say, until Cliff and Matt [Wilson]’s artwork comes in, and then I’m like, “Oh, this feels great!” And then the sickness starts up again, and I have to find a way to treat it. It’s very obnoxious to describe writing as this diseased process, but I guess that’s how it feels.

Chiang: The heart of the story is Brian’s need to explore whatever is consuming his thoughts. With Saga, it’s very much about family. With Paper Girls, it’s about getting older and looking back, and thinking about what you wanted to achieve when you were younger. There’s this grappling with what’s going on in our lives now, and we put a lot of ourselves into it because of that. Hopefully it resonates.

Vaughan: It’s a hopefully somewhat benevolent midlife crisis. [Laughter] I just remember sitting down before we started working on it, and so much of what Cliff brought up (I’m talking about the Challenger Explosion, for example) made it not just into the first issue, but the entire series. I just thought, “What parts of the 80s made us?” or “What did we carry with us? What are we imparting to our children? What have we been able to get rid of?” That’s not something we had an answer for. When you ask what was driving us, it wasn’t like, “Oh, I need to impart this wisdom to young people.” All I ever got was fucking confused. Working on this made me feel better.

The book has that particular point of view, of being 12, 13, or 14. That’s the time when you do stuff like take poetry seriously. You’re taking your emotions to such an extreme, and it’s difficult to believe they are going to come back down or be balanced in some way. At times, Paper Girls feels like an extreme book. It feels like a book that is bumpy.

The book has that particular point of view, of being 12, 13, or 14. That’s the time when you do stuff like take poetry seriously. You’re taking your emotions to such an extreme, and it’s difficult to believe they are going to come back down or be balanced in some way. At times, Paper Girls feels like an extreme book. It feels like a book that is bumpy.

Vaughan: Whenever I read a review that says, “This book is a love letter to ‘blank,’” I’m always like, “I do not want to read that book,” because I’ve read other people’s love letters. They are boring and self-indulgent. [Laughter] I never want to write a love letter to a period of time. So, I’m flattered by your seeing the anger and venom, even though this is ultimately a pretty sweet book about four friends. There’s always some bile to be had. [Laughs]

Well, it’s earned. I feel for somebody who bails on Paper Girls before the end because it’s that conclusion. Obviously one of your skills, and Cliff and I have talked about this before, is that you’re very good at that thing that everybody else is now trying to get really good at, which is to close the story in a way that makes people want to find out what’s going to happen next.

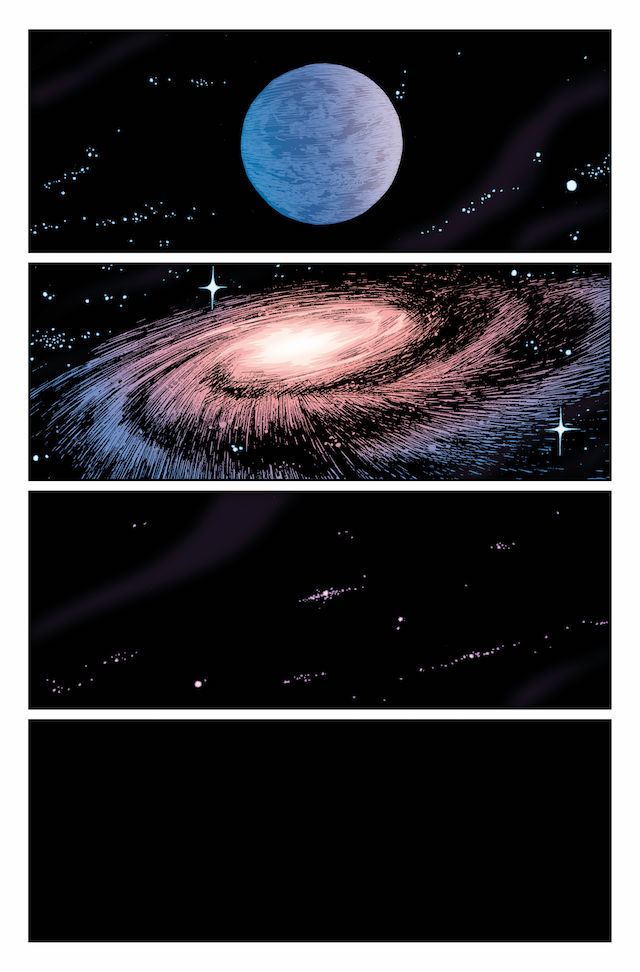

There are definitely nuggets throughout Paper Girls worth following, but the real meat of satisfaction is that final issue. That’s when the pacing changes. I want to know specifically how that happened. The page where we pan out of the world, and then you drill right back in so that she can say, “Hey, can we just keep going?” What’s the script for that look like? How did that drawing, that decision, that timing, that sequencing come about?

There are definitely nuggets throughout Paper Girls worth following, but the real meat of satisfaction is that final issue. That’s when the pacing changes. I want to know specifically how that happened. The page where we pan out of the world, and then you drill right back in so that she can say, “Hey, can we just keep going?” What’s the script for that look like? How did that drawing, that decision, that timing, that sequencing come about?

Vaughan: I love how that sequence follows the playground sequence, which is my favorite, which is a total invention by Cliff. I just had them at this weird, little covered bridge I thought would be nice, but Cliff has them smoking at a playground, which is so heartbreaking and familiar and relatable. Love that. I knew I wanted to have an extra mean-spirited moment, where it looks like we’re going to end, and the girls are not going to be there. To have them pull out to the scope of everything they experience, but then push back in … yeah, I guess I just felt Cliff calling me to the right ending. I can’t remove his, I don’t know … Cliff is like the god of the story. Cliff, do you have thoughts about that ending? It’s executed so perfectly.

Chiang: Those pages were easy to draw. [Laughter] Like, there wasn’t a lot to it, but at the same time they were also very difficult for me to conceptualize because I tend to try to drill down into the emotion of a panel, and with these it was far more removed. It almost became a technical exercise of making you feel this camera movement. Because once that ends, you’re brought right back to the girls so powerfully and with such a focus on their emotions that you need that difference of it being cold, and getting colder and colder, and then the rubber band snaps back, and we’re where the reader wants to be.

Vaughan: Yeah, I was trying to capture the scope of what they had been through, and how monumental it is that they’re able to make this decision to stay together.

Chiang: Fate of the universe.

Vaughan: But we’re not buying back the fact that Mac is still going to die. It’s extremely dark. She’s going to die. The girls have not stopped the worst things that will happen to them. We don’t really get to decide what the length of our mixtape is, but that they’re able to change what’s on the tape feels like a big, cosmic moment.

Chiang: One of the things I thought while reading the script is that throughout [the series] there’s been an interesting exploration of religion. I don’t know how intentional it was, but we’ve gotten bits and pieces of it. There’s a lot of Catholic imagery. The doctor, Dr. Brownstein, brings up her idea of religion and what God is, and how that relates to their lives and their destinies. That final camera move feels like we’re going from the very specific lives of these girls to something larger and more universal, then back to it. It seemed to be this idea that we do need to focus on how we live our lives now, as that is what makes up the universe.

Chiang: One of the things I thought while reading the script is that throughout [the series] there’s been an interesting exploration of religion. I don’t know how intentional it was, but we’ve gotten bits and pieces of it. There’s a lot of Catholic imagery. The doctor, Dr. Brownstein, brings up her idea of religion and what God is, and how that relates to their lives and their destinies. That final camera move feels like we’re going from the very specific lives of these girls to something larger and more universal, then back to it. It seemed to be this idea that we do need to focus on how we live our lives now, as that is what makes up the universe.

Vaughan: It’s been so long since I’ve written it down, and since I’ve read it. [Laughter] I like discussion, and I hope people will walk away with different things that are interpretation. I would be so interested to hear if it works because it’s a very different kind of final issue. It’s not a slam-bang-action-so-quiet.

That’s kind of a universal thing happening right now — this post-belief culture where Christianity continues to hemorrhage attendees and believers in the U.S. at the same rate that already happened in Europe. But there has to be a replacement for those questions that you’re talking about. There’s this idea that if you’re going to replace church, you’re going to replace belief systems with an embrace of culture. It’ll basically be a worship of extreme fine arts and that kind of thing. What that leaves out entirely, though, is religion in social life, and that is the purpose of the church for so many people in the U.S. It’s a place where, like your Paper Girls — people from different ethnicities, people from different backgrounds, people who are going to struggle with an illness and die at a young age —used to go to find their community. It’s where you could go to get a job, or find some of kind of peace, or at least social interaction. If you take away church, you no longer have that. You no longer have that place for them to go. Basically, they have to pay for everything. We don’t have public spaces. What’re you going to do, hang out at Barnes & Noble?

Vaughan: Cliff and I talked about religion a lot and what our backgrounds were. Thinking about what the 12-year-old version of me would think meeting his balder, older self. Like in some ways there’s, “Oh, you’ve fulfilled all these dreams, getting to be a professional comic book writer,” but also how strange it would be for a devoutly Catholic kid to see his current self? To ask, “What have you become?” Would he be scared of me, or disappointed, or ashamed? So yes, religion was such a part of Paper Girls at varied stages, hopefully without coming down on … I don’t know where it comes down. I guess I’ll let people decide. I’m still not sure where I’ve come down on it all [Laughter], but the answers are somewhere in the sacred texts of Paper Girls #1-30. If you read them closely enough, enough times, you will reach divinity.

Are there other big conversations that recurred throughout the making of this thing?

Are there other big conversations that recurred throughout the making of this thing?

Vaughan: Oh, definitely. Every arc I think we would take a moment to be like, “Hey, let’s calm, catch up, and talk about what worked and what didn’t,” and Cliff would always come up with something brilliant or just say, “Man, I would really love an opportunity to draw some robots. Big or small.” [Laughter] At first, what really set the tone for the series was just Cliff recommending the look and feel of it, and just what we wanted to talk about. Like, subjects we wouldn’t be bored by four or five years from then.

So, what was the actual workflow interaction like while you were creating this?

Vaughan: You’re the master of this, Cliff. How’d it work?

Chiang: It’s surprising. We would talk a fair amount, and yet at the same time once I got a script, I would rarely have any questions. For me, maybe as an English major, I just forced myself to grapple with the text, and see what was there and try and answer as much as I could. If there was anything that was unclear, then I would just shoot him an email, and it would be a one-word email back. But what that meant to me was we just trusted each other. We were both doing our best, and we were both putting our best feet forward, and saying what we needed to say. I could tell that there was no wasted effort on Brian’s part. Everything was surgically precise in terms of his word choice and the pacing of it. So, I had to honor that, and then just draw it. When that was done, Brian was reading it. There didn’t need to be a lot of back and forth and collaboration in a very day-to-day, “This panel should be here and maybe change that,” kind of way. We both respected each other’s work and wanted to do our best, and that’s the way it was with the whole team, really. Everyone brought their A-game.

Vaughan: Trust is the right word. After I send the script, artists will usually send thumbnails, and if I catch something that I described wrong, we will talk about it. But Cliff would never send thumbnails because he didn’t need to. There have also been books where I would get the artwork back, and I’d be like, “Oh, I need to take another pass at this dialogue to play off the strengths of the art,” and there was so little of that. Just at each stage. I think we all worked together so long, Matt and Jared [K. Fletcher] and Cliff and I, that there was this tight type of collaboration that involved just trusting the other person to be alone in their room [without any of us] looking over their shoulder. I love that. That at each stage this person is going to make your work better, so just concentrate on telling the next story, so they’ll have something when they’re finished. It’s very ideal. It’s a lovely way to work but, as I’ve feared, it’s also taught Cliff (which I’m sure he’s known all along) that he should just write, and color, and letter his next project. He should just do everything himself because it’s like, “Oh, Cliff is the master of each of these. Once he cuts this dead weight loose and is free of us, we’re doomed.”

No, you’re doomed. It works out fine for me. [Laughs]

Chiang: It was like running a relay race, and everyone had their part in it. I think that’s what helped everybody stay super focused and do their best because it wouldn’t be just one person the whole time, or anybody carrying anybody else. Everyone just got to show their stuff and try and not let the rest of the team down.

Vaughan: Writing for television is challenging, but in a lot of ways, it’s not as hard as an ongoing comic book. Even with this humane system that we’ve come up with of telling an arc, taking a break, and coming back. It can still feel like an endless marathon.

Chiang: It’s grueling, yeah.

Vaughan: I never want to hear about writers asking artists to redraw pages. I try to almost never do that. Then it’s my fault. It’s something like, “Let’s do it better next time,” but you just have to keep the train running. I wouldn’t do it if I didn’t think that great work comes out of it, but it’s just exactly the right amount of pressure to make very good stuff happen. But it’s weird. It’s a weird process.

Was it that way from issue one all the way to the end? You’re describing a process that, if I sit down and read this and I don’t know you guys, I’ll go like, “So it’s just perfect is what you’re saying? It’s perfect.”

Vaughan: Yeah. I think it’s pretty perfect. I love it. I really think it holds together so well, and I’m very excited because I think it’s a challenging book. I do think it’ll read completely differently for people who are going to sit and binge it in one sitting. As much as Saga is an adult book, it is kind of a pleasure to know you can just sink into it. Paper Girls is tough. I know the complaints are always, “It is confusing. What the fuck is going on?” and “Who are these people?” I wanted to do a book that, when I was 12, I would have reread the issues before I went to the next one. I know it’s strange, but I’m super proud of it, and I think it ends beautifully. I’m curious to see what people make of it when it’s altogether.

Cliff, Brian has done multiple creator-owned books at this point in his career, whereas you have done work for DC. Was there any desire on your part, that if you were going to walk away from an exclusive contract, to do something that is a little bit more along those lines? Or were you just like, “I want to work with BKV, and I want a challenge?”

Chiang: I was scared when I read the pitch, to be honest. Leaving the nest of DC to do something like this did not feel like a slam dunk, and Brian said that himself to me. Oddly, that’s what made it more compelling, though, to know that there was a creative risk involved. I was scared of this idea, of drawing 12-year-old girls on bikes. I wasn’t sure if I could do that. There was nothing in my career that really prepared me for that, but the challenge of it was exciting, too. If you’re going to do anything, there’s got to be some risk to it. You got to have some skin in the game.

One thing we haven’t really talked about is that you’re a couple of middle-aged straight guys doing a book about 12-year-old girls. When you started this book, that was one thing. If you started that book today, now? That’s going to be the first thing that comes out of anybody’s mouth.

One thing we haven’t really talked about is that you’re a couple of middle-aged straight guys doing a book about 12-year-old girls. When you started this book, that was one thing. If you started that book today, now? That’s going to be the first thing that comes out of anybody’s mouth.

Chiang: We had blinders on, and unfortunately that’s our privilege showing. When I got the pitch, of course I showed it to Jenny [Cliff’s wife], and she loved it. There wasn’t a point where she said to me, “Are you sure you’re the right person for this book?” It was just, “Are you excited about this? Then you should do it.” You’re right. If we had thought about it more, maybe the team would have been different. Or maybe we would have gone with a different story. I don’t know.

The primary audience is probably going to be younger, female readers. They might read a superhero comic like Miss Marvel, but they’re going to look for stories about people like them. You guys produce that thing, but you guys are not those people.

Vaughan: Today, would I have pitched Paper Girls to [Cliff, Matt and Jared]? Probably not, but I guess part of it is this is one of the first books I’ve worked on that hasn’t had a collaborator who happened to be female. It’s something I probably foolishly didn’t think about until Cliff assembled those pictures of the four of us as a bunch of 12-year-old geeks to put in the back of the book. I was proudly showing it to my wife, but when I did, she didn’t exactly cringe, but I noticed her discomfort. I suddenly realized, “Oh, it’s a little weird, this picture of four dudes in a book about four girls.” It’s like that great Tumblr, “Congrats, You Have an All-Male Panel!,” which is just pictures of all of these panels that have only men talking about female empowerment or whatever. It was in that moment I was like, “God, what an idiot that I never thought about the optics of this, much less the ethics.” But I was also like, “Well, the ship has sailed.” At that point, could we just try and tell the best, truest story possible?

Chiang: Yeah, I think knowing that, and as the series went on, I feel like we tried to be as conscientious as we could about that fact. And I think there’s a difference between writing a story about these girls and speaking for them.

Vaughan: It’s heartening to know that, as the television show comes to life, a primarily female team will drive it. And it’s just nice to see how many readers who happen to be women have responded to this book. So, I’m heartened both that they’re being included in the process now, and that we wrote something that hopefully doesn’t feel off-putting or like a bunch of carpetbaggers trying to come in and talk about the experience of being a 12-year-old girl. I think, for me, it was always – whether it was Y: The Last Man or Saga or whatever – just trying to write about humans that are so vastly different from each other.

So, are you ending it the way you wanted to end it? How much of it changed over time, over that period of years that you guys were working on this thing?

Vaughan: Cliff’s idea of, “I think one of the first things that should happen is to have the girls, at least one of them, meet themselves at the age that we are now.” … That’s really when the book became itself. That sort of “present shock” is not something you usually see in time-travel stories. It’s usually taking people from the contemporary world and visiting somewhere else. Just the power of bringing these girls from 1988 to, whatever it was, 2016 at the time. It gave life to the book, and it pointed it in the right direction.

There were big signposts of KJ and Mac kissing, or Mac’s discovery of her leukemia, or the fact that she wasn’t going to be cured. Most of these major signposts were there. But just the little friendships and watching the girls become the young women they are at the end, so much of that is just Cliff and the way he portrayed them and drew them together. It would just be so exciting. I’d be like, “Ah, I‘d just really like to see KJ and Erin hang out for a while” or “Just Mac and Tiffany.” Each creation brought out something new. Plot-wise, it was exactly the story I wanted to tell. Tonally, it got better than I’d imagined it could be. Thanks to Cliff.

Chiang: That’s the way our collaboration really worked, is that it was over the period of 30 issues and not on a panel-by-panel basis. It’s just that we would do one issue, and then react to that, and the next one, and the next arc, and the next arc. I think the series ends on the perfect note. For me, it’s having those quiet character moments after all the science-fiction hijinks and getting to say goodbye to the characters by sitting with them. That was really what I wanted as a reader and as the artist. I wasn’t ready to say goodbye to them.

Have you ever gotten to do anything like that in your work? Almost everything you’ve done has been something you’ve had to hand off to somebody else, right?

Have you ever gotten to do anything like that in your work? Almost everything you’ve done has been something you’ve had to hand off to somebody else, right?

Chiang: Yeah. Being able to put a bow on it and say, “That’s it. There’s no more. This is our story exactly as we wanted to tell it,” and being able to present that to the reader, that’s pretty great.

Vaughan: Just know, though, there will be no Beyond Paper Girls or old-timer spin-off. Endings are what give things their meanings. So I loved just getting it to that finish line. As much as we had to plan for these 30 issues, there was no guarantee. Like, I can’t stress how tense it was to put this book out. It’s hard out there and creating your own series about four 12-year-old girls was so not a sure thing. I was like, “This might be a five-issue miniseries, Cliff, and we’ll find a way to put a bow on it at the end.” So, it’s just cool to have gotten to tell this story, and that it was profitable for all the creators involved. It’s just important to me. I wanted it to be a good experience for these guys and not be like, “Oh, I wish I had done anything but create our own book.”

That’s one thing I was curious about. Was there ever a consideration of going to First Second, or going to Scholastic, or going to any one of the big five? I mean at this point the both of you have enough of a BookScan track record, and you have enough of a presence to just do something with an advance and structure it differently. You could do something that’s going to have more immediate access to that particular market as opposed to going through the Image format with single issues and then collecting it.

Vaughan: Not from me because I’m so grateful to Image. It’s wild to see these big announcements with Amazon and stuff, and Image benefits not at all from them. They take no percentage of any of this. They’re just supportive. So, I’m extremely loyal to them, but I’m also loyal to the direct market. I don’t think Paper Girls would have been the success it was if we had just done it as six standalone graphic novels. That there are still tens of thousands of hardcore readers who are willing to come out and read it chapter-by-chapter, and then spread the love so that, when the trade does come out, the audience is there … I like that system. I like writing something that costs $2.99 or $3.99. That feels satisfying. So, no, I still like comics. I would sooner do this again, I think, then to run off to a YA publisher and do a graphic novel.

Chiang: I struggle too to think, “Where would it fit in?” You mentioned earlier that there’s a weirdness to Paper Girls. There’s an edge and maybe even a venom to it. I don’t know where that fits into the market with the way that most popular books seem to be. It’s YA adjacent, maybe.

Also, this is just a conjecture and curiosity, but you’re not going to go to one of those places and be unedited. You’re not going to go to one of those places and be able to dictate as much. I love both of you guys, but the reason I get out of bed is Jared K. Fletcher, and I don’t know that First Second is going to let Jared do whatever he wants.

Vaughan: It was such a good band of four people working together in every way. I mean, Jared designing an entire alphabet for this? To have that for the hardcore readers who would begin to work with deciphering it immediately, something that we thought would take years to do? Like, yes! That’s just an added expense that you get with a talent of Jared’s level that, yeah, we just could have done it in house or something, but there’s a real artistry to that. Yes, I’m glad you’re a Jared fan as well.

[Stone and Vaughn fanboy over Jared for about a minute.]

Cliff, what was Jenny’s response to showing up in the book?

Cliff, what was Jenny’s response to showing up in the book?

Chiang: Oh yeah, it was awkward. At first, we did have a conversation about it, and a lot of that was me explaining I didn’t want to just make up a person. I wanted older Erin to have roots, and that I personally feel connected to Erin because it was such a gift to have her be kind of our entry point for the series, and that we’re seeing an ‘80s coming of age story through an Asian girl’s eyes. So I felt very connected to that character, and then when we jumped to the present day, I wanted that character to still feel connected to me, and the only way I could do that was by making her look like Jenny, and even though old Erin’s life didn’t turn out the way she wanted it to, I wanted to be able to project as much of my love and emotion for my wife into that character, so that she felt like a real person and not just a convenient plot device.

It’s very effective. When I read the book again, I remembered her as being more a part of the book than that. Like just on the page, she has such a resonance to her, and she is alive in the book. She really jumps out.

Vaughan: I’m so glad it happened in the second arc and not later because I think it really solidifies the heart of the book in a lot of ways: about meeting yourself, and your older self-thinking that your younger self is disappointed in you, but then they’re not, and there’s just sweetness to it. It’s about learning to love yourself or being able to actually give yourself a hug. Those pages were just so moving. It really gets at so much of the general arc of Paper Girls, too, and everything that comes after that.

Most of the people I work with don’t read comics, but Paper Girls is the one that crossed that line. The thing that people seem to respond to most emotionally is everything with older Erin. The relationship between those two lays the groundwork for so much of what fuels her. Of her being able to really trust herself and go forward and face such unusual circumstances. So much of that comes through in those particular moments with older Erin.

Vaughan: I agree with that 100 percent. I just love that hug that happens outside, and that it happens outside a mall [Laughter] that no longer exists, which would have been so unthinkable to my 12-year-old self. When younger Erin asks older Erin what happened to the mall, and old Erin is like “Amazon’s a bitch,” … it is weirdly prophetic, or I’m not sure what it is, but I think about that panel a lot. I’m a Prime subscriber. I love them, but I also know that I want to support my local comic book retailer. I hope we will be able to live in a world where there is always both, and Paper Girls will be the peace, the 12-year-old superstars who broker a peace between the two sides. That will be what the Paper Girls comic is [Laughter] … brick and mortar retailers and online outlets.