Jonathan Fetter-Vorm is known for his nonfiction graphic novels Trinity and Battle Lines and the just-released Moonbound. Each book takes an unconventional approach to presenting history, and I joked with Fetter-Vorm that Moonbound consists of two stories, one a very detailed account of the Apollo 11 mission and the other the history of the world up to 1969. But it’s the way that he combines these two very different elements – a detailed story of engineering and applied science on the one hand, and this outlandish, seemingly impossible idea about the universe and our place in it on the other – and how these two things collided 50 years ago which is precisely what makes the book so interesting and powerful. In so many ways, we’re still trying to deal with what those events meant and what they mean for us going forward, something that the book’s Epilogue wrestles with, but by not just teaching us about these events but placing them in a different context, Moonbound allows us to ask different questions and understand the history in new ways.

Jonathan Fetter-Vorm is known for his nonfiction graphic novels Trinity and Battle Lines and the just-released Moonbound. Each book takes an unconventional approach to presenting history, and I joked with Fetter-Vorm that Moonbound consists of two stories, one a very detailed account of the Apollo 11 mission and the other the history of the world up to 1969. But it’s the way that he combines these two very different elements – a detailed story of engineering and applied science on the one hand, and this outlandish, seemingly impossible idea about the universe and our place in it on the other – and how these two things collided 50 years ago which is precisely what makes the book so interesting and powerful. In so many ways, we’re still trying to deal with what those events meant and what they mean for us going forward, something that the book’s Epilogue wrestles with, but by not just teaching us about these events but placing them in a different context, Moonbound allows us to ask different questions and understand the history in new ways.

Alex Dueben: I know a little about your background like the fact that you studied history in college and were apprenticed to a letterpress printer after college. How did you first start to make comics?

Jonathan Fetter-Vorm: I remember as a kid finding Elfquest at the library and being surprised that there were comics out there that weren't about superheroes. I started making comics with a buddy of mine around then. We actually had laminated library cards in middle school so that we could avoid the bullies in the schoolyard during lunch. We'd hang out in the school library reading and drawing comics. That was the beginning. It wasn't until college that I started taking it seriously as something that I could do as a career. I had begun to fold more of a scholarship aspect into it my work, and I realized that doing nonfiction comics had some potential.

What in college made you think about comics in this way?

It was a class on medieval history, we had to read Beowulf and a lot of the supporting literature around it. I was hooked. I got a grant to translate it from Old English, and illustrate my translation, and that was a good start because Beowulf itself is a very strange text, a pagan oral tradition that was written down by Christian monks who then put their own gloss on the story. It's several different voices all mashed together. It just made sense to me as a comic—it has the warrior and the monsters, but also it gave me a way to have the artwork work against the text, to give it a counterargument. The idea that the poem as we know it has had so many different evolutions through its life, maybe prose or verse aren't the only ways to tell this story.

So what was the process between making that comic in college and starting Trinity?

So what was the process between making that comic in college and starting Trinity?

There were probably ten years in between those projects. In the meantime I had started working at a letterpress shop, living with that same friend from middle school – Tom Biby. After work every day we would draw comics together at night. It felt like we were the guys from Chasing Amy (except without all the drama). We started up a publishing outfit where we made handmade letterpress books. We took old texts, trying to reinterpret them graphically and lyrically. I had a lot of fun doing that, but it was a lot of work to print and bind every book by hand. We sold them at conventions around the West Coast. This was my first introduction to the culture of comic book conventions. We met a lot of great people but at the end of the day we both realized that it was just so much work to produce and sell these books.

Eventually I did some interviews at various publishing houses to be a book designer. I was actually in the process of being politely told that I wasn’t qualified – which is fair, because I’m not a very good designer – when one of the editors at FSG walked by and saw my portfolio. This was Thomas LeBien. He had conceived of the idea of Trinity but needed an artist. At the time I had very little knowledge of atomic history. My grandfather worked on the Manhattan Project and had told me some strange stories about what that was like, working under such intense secrecy, but otherwise I was coming to the history with a blank slate. As soon as I started researching it, I realized this is exactly what I wanted to be writing about: J. Robert Oppenheimer, the enigmatic physicist/poet who toyed with the fundamental stuff of the universe, and the devil's bargain of atomic energy. It became an obsession. I bought a Geiger counter and drove all around the West looking for uranium mines and nuclear test sites. That started my career as a graphic novelist.

What kinds of texts were you playing around with when making letterpress comics?

Renaissance and classical texts, mostly. We also wrote some original stuff. I liked this idea of taking things that are either so deeply ingrained in the public consciousness that we sort of forget about them or think we already know everything about them, or texts that have been overlooked as too stuffy, the kinds of things that were assigned in high school – like Beowulf – that maybe you thought were boring the first time around. These seemed like good opportunities to go back and reinterpret with the freedom of a graphic treatment. I guess that’s my M.O. now too for history. I’ve taken some of these fulcrum events in modern history, events that we're all taught in school but that also seem too big for a quick history lesson, and tried to find new ways to talk about them. I'm drawn to the small moments in the margins of these great events.

Was Moonbound a suggestion or something that you pitched?

Was Moonbound a suggestion or something that you pitched?

That was my first real pitch. The first project I conceived in whole.

So what was it about Apollo 11 and the space race that fascinated you?

I really liked the tension between the fantasy of it – the scifi aspect that compels us to imagine what other worlds are like – and the nuts and bolts history of America at its engineering height. The machine of the military-industrial complex was charging full steam ahead and somehow it appropriated – and was appropriated by – this crazy scifi adventure. It seemed like a fun conflict to illustrate.

In so many ways it is outlandish. Let’s shoot a bullet to the moon!

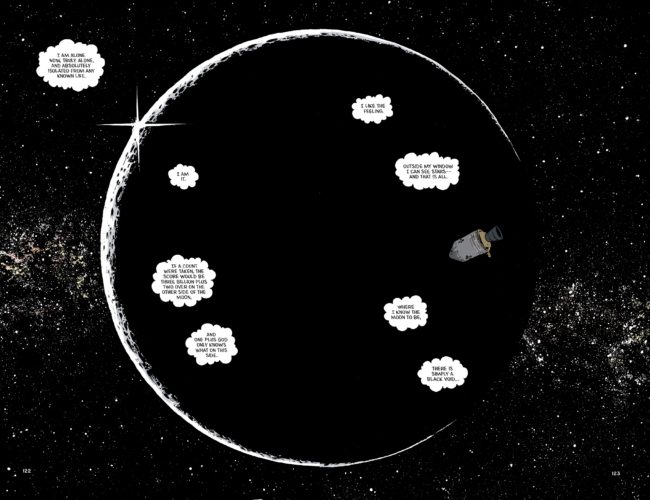

And put people on the bullet! And they’re going to be okay! The flipside of that is that it’s entirely outlandish, but also entirely mundane. You listen to the astronaut transcripts – this stuff is digitized and accessible – and it’s like it's just a few guys going on an epic road trip. They’re incredibly talented and very well trained and competent. They’re just doing their jobs and it all mostly works. In the aftermath it’s hard to square this dream that we’ve been collectively dreaming for centuries with the very dry reports of what it was like up there. We came back with a bunch of rocks and some anecdotes about the light and the landscape, but the height of the dream doesn’t really match up with the reality.

You touch on this in the book. These astronauts were fighter pilots who were trained to cut themselves off from emotion, to focus on the task at hand. They were engineers, not poets.

They certainly weren’t poets, no. When I decided to do Apollo 11, I thought that it would be an extension of Trinity. Similar themes – big personalities, doing big, audacious things at the intersection of science and imagination. Which in some cases it was, but mostly it was an engineering story. Mostly it’s the story of the government and private contractors applying previous knowledge to solving engineering problems. There was no Oppenheimer. There was no team of wild-haired, wide-eyed Jewish émigré physicists who were escaping Nazism and dissecting the very fabric of matter . No doomed, sad-eyed poet quoting the Bhagavad Gita at military test sites. I was a little disappointed at first when I couldn't find the strangeness and magic in this story. Eventually I did, but I had to expand the scope of my book. That’s how I ended up writing about things happening four and a half billion years in the past.

Trinity is about the building of the bomb and explaining the science of it, but at the center you have Oppenheimer, and he’s someone who was very conscious about what that meant on so many levels. In a way very few people in the heart of anything this big think. There was no one in Moonbound who thought that way, and certainly no one so central who thought that way.

Trinity is about the building of the bomb and explaining the science of it, but at the center you have Oppenheimer, and he’s someone who was very conscious about what that meant on so many levels. In a way very few people in the heart of anything this big think. There was no one in Moonbound who thought that way, and certainly no one so central who thought that way.

I think you’re right. But even people on the periphery didn’t think that way. The New York Times on the eve of the launch produced this great feature where they polled a wide swath of luminaries, people like Nabokov and Timothy Leary, activists, philosophers, and all sorts of people. I thought this would be a useful roadmap, something to help me understand what the moon landing meant, but even the greatest literary and poetic minds couldn’t quite wrap their heads around it. It’s a hard topic to pull meaning out of. That was the main struggle of this legacy. Was this the most significant event in human history? That was how it was pitched. In the aftermath, it doesn’t seem like it was. But I guess that remains to be seen.

Trinity is probably the closest you came to making a book with a traditional structure and arc. Battle Lines was more fragmented. This is the story of this triumphant moment – and then everyone shrugged and walked away.

It’s true. One of the challenges of writing the book was that it doesn’t fit a classic dramatic structure. There are moments of tension and moments of tragedy, but mostly it’s a story of success. They leave, they make it there, they come back. A lot of times when people try to tell this story, they try to pump up the drama either by going into the personal lives of the astronauts or by showcasing the lunar descent where the computer malfunctioned, though in reality, that bit of drama lasted all of five minutes. I wanted to avoid those traps because this is not necessarily a climactic story. In fact in some ways this is an anti-climactic story. Which is a hard thing to put on paper. I think it’s an important way to tell it because that’s truer to how it has affected us as a culture.

They were drilled for months on every possible contingency. In an odd way, the flight was supposed to be anticlimactic.

Exactly. The idea was, with enough training, with enough simulations of every possible contingency, NASA could all but eliminate the risk of failure. Of course the whole Apollo Program was incredibly risky, and the astronauts were frank about the ever-present risk of death. I don't want to diminish the audacity of sending men to the moon. But it was in no way a “hail mary.” That said, William Safire wrote a speech for Nixon to read if they Apollo 11 astronauts died on the moon, which was a really moving eulogy.

Which was really moving and intense. You have to wonder how things would have happened differently if that happened.

Which was really moving and intense. You have to wonder how things would have happened differently if that happened.

Yeah, it's hard to imagine how different American history would have played out if the mission had failed. Actually, that would probably make for a better, or at least way more intense, comic book: an alternate history where Apollo 11 never came back.

So when you started thinking about Moonbound, to put it broadly you have two threads in the book. One is this very detailed account of the Apollo 11 mission, and the other is the history of the world up to that point.

[laughs]

I’m exaggerating slightly.

Like I said earlier, I wanted to work against the temptation to make this a climactic story. I wanted to start with what has traditionally been the most dramatic moment, their descent. Once I got that out of the way there was no pretense that I was going to use that as a dramatic hinge. One of the first sparks of this story for me was reading the mission transcripts of the moment shortly after Neil and Buzz landed. Their mission plan said that they were supposed to take a five hour nap before they did their moonwalk. At this point they’d been awake for almost a day. There’s this great moment where Neil looks at Buzz and says, essentially, let’s deviate from the plan. They tell Houston they're not going to take a nap. The subtext being, there’s nothing you can do about it because we are farther away than humans have ever been. Ultimately, they compromise and take a short rest period. I love that image of these two men as far away from home as possible, not wanting to nap because they’re on the cusp of seeing a new world. When I first read that in the transcript I thought, I want to focus on what it was like during those hours in the lunar module right before they get out. That’s a story I hadn’t seen before. It’s usually glossed over because once they land we try to get to where they’re out on the moon as quickly as possible. I like thinking about all the drudgery of getting dressed, of taking out the trash, all these little things that you don’t associate with the moon mission, but that were integral to the success of it. Given that, I wanted to condense the scope of the Apollo mission as much as possible. I had a suspicion that in the historical chapters I was going to go pretty far afield, so the more condensed I could make the Apollo stuff the easier it would be for me to get a little untethered in the history.

Another way you contrast the two threads is in how you use color.

Color has always scared me. Trinity was black and white and Battle Lines was essentially black and white but I’m trying to force myself to get more comfortable with color. I started out by creating a color palette that replicated the feeling of Kodachrome, something that had a mid-century feel. I knew that I wanted the Apollo chapters to be in full color, so that the reds and blues and golds of the astronauts' suits really popped against the gray tones of the moon itself. Once I had that full color palette I broke each historical chapter into a single color from that larger palette. It worked pretty organically from choosing the color first and then figuring out how to deploy it. And then by chance, I found someone to help me out. Laura Martin graduated from the Center for Cartoon Studies and sent out postcards to everybody that she thought would be fun to work with all across the country that said basically “I just graduated, I do comics, I’ll do anything you need me to do.” She sent one to a friend of mine who runs a graphic design firm here in Kalispell and they passed it along to me. This postcard made its way from Vermont to Montana and we started a great collaboration.

You grew up and live today in Montana, which is big sky country. It’s beautiful up there. What was your relationship to the sky? Were you interested in space as a kid?

I’ve always been fascinated and drawn to space, but I’ve never wanted to be an astronaut. I think because I've always been a little terrified of the void. The stars out here at night are amazing and some of my best memories of being a kid are sleeping out on the lawn under the Milky Way or the Northern Lights. That kind of sky kindles all sorts of wild thoughts. I wanted to try and capture some of that sense of vertigo. But as soon as I started drawing space, I realized that it’s really hard to draw. Especially in pen and ink. I mean, Tillie Walden can do it, but for me it was a real struggle. So I was never enamored of the actual space program—the rockets, the spacesuits, all of that—but space itself has always felt like a terrifying and thrilling thing to think about.

You tried to convey some of that fascination and wonder and obsession in the historical chapters.

I think I identified most with those figures. People like Kepler, who knew that there was never a possibility that he would go to the moon, but he managed to get there in his imagination.

You did a lot of research and you were clearly interested in finding a way to talk about the space race in a way that doesn’t get discussed.

I wanted to get behind some of the myths that have endured about what the space race was and what it meant. Sputnik is a good example. The legend goes that Sputnik was this huge shock to the American consciousness. The press certainly built it up as that and a lot of people certainly felt that way, but the reality of it was that it wasn’t a shock to Eisenhower or to anybody in government who knew what was going on. In fact, it was a strategic victory for the US. Sputnik meant that there was now a precedent for American spy satellites. I thought that was a much more revealing narrative than the standard, “now that the Russians have a satellite, the Americans will start taking space seriously.” It wasn’t like that. The story behind the scenes was a lot richer and more complex.

The background of the Russian space program was fascinating and horrifying – like a lot of Russian history.

Exactly. Sergei Korolev, the Soviet Chief Designer, was one of those tragic figures. Although despite great hardship, he did end up realizing his ambitions. Or most of them. He didn’t live long enough to see people land on the moon.

The American space program as you point out, had women and people of color working on this, but they were excluded from most roles and the work of people like Margaret Hamilton was downplayed. The fact that NASA was located mostly in the South meant they had segregated facilities. There are a lot of things you talk about that we don’t usually think about or consider in this history.

I was a little insecure at first about the idea that I was telling a story that was almost exclusively about white men. Eventually, I realized that that was not a problem of the story; that was a problem of the history. There are very important exceptions to that rule, but NASA itself was structurally designed to exclude the contributions of women and people of color. I think that’s an important aspect to consider. Speaking of counterfactuals, how different would our country and our space program have been if women had walked on the moon? Maybe I should switch gears and do alternative history.

Jerrie Cobb and other women not only met the same standards that male astronauts did, they sometimes beat them at physical and psychological testing. But ultimately it was decided that didn’t matter, there wouldn’t be any women astronauts.

Jerrie Cobb and other women not only met the same standards that male astronauts did, they sometimes beat them at physical and psychological testing. But ultimately it was decided that didn’t matter, there wouldn’t be any women astronauts.

And she did it without having a clear path to being a female aviator! The men were fast tracked through the air force and test pilot school, it was easier for them to get enough flight hours to qualify – women, however, couldn’t do any of that. Some of the most qualified female aviators were what was called Aerobats. They did airshow acrobatics. They did whatever they could to get into a cockpit. In a way, I'm more impressed by the First Lady Astronaut Trainees (or FLATs as they were called) for what they managed pull off, despite deep structural obstacles, than the male pilots, who had established routes into astronaut training.

As far as detail, NASA was very good at documenting these events. So you had almost too much research information available, but what was your biggest challenge in tackling this?

It was definitely a blessing that there is so much material freely available. Especially for me because writing this book coincided with the birth of my first child. That meant I didn’t have much time or opportunity to travel for research. I wouldn’t have been able to write this book if there weren’t so much freely-available documentation. One of the biggest challenges was on the visual side of things. There’s a whole aspect of doing graphic histories that you get to avoid when you’re doing a prose history in that when I show the astronauts in the lunar module, for example, it’s not a prose historian’s responsibility to delineate every knob and switch unless they're important for the narrative. But in all of these essentially throwaway panels where I have astronauts talking to each other, I still have this need to show the O2 hookups, or to figure out are the armrests down or up at this point? Are their helmets on or off? That kind of research took up the most time and I'm not sure how much of it is even apparent in the finished book. But for my own sake, I wanted to figure out how to make sure everything was in its right place. In that sense NASA was great because there’s a document for everything. There's a memo that lists when the astronauts had their gloves on and which gloves they had on. It’s just a matter of finding those documents and double checking it against where in the story we are. I’m not sure how many people would have called me out if l was wrong, but I like to think that most of what you see in Moonbound is accurate to what it was like.

You made the point that this is an anticlimactic story in many ways and I thought about those couple pages where you explain how spacesuits were made. How Playtex had seamstresses sewing these suits by hand. “Although the Apollo space suit has become an icon of the space age, a symbol of a future beyond Earth, it’s really a product of traditional techniques and old-fashioned artistry.” As you said before, this was an engineering story.

I got to include almost everything that I wanted to include but if I’d had more time, more energy and more pages, I would have liked to include a chapter that was totally from the perspective of the workers who were subcontracting for NASA. At the height of the Apollo Program, there were 400,000 people working on this project. There were facilities all across the country manufacturing some little part of the larger machine and it often came down to classic know how and craftsmanship. You find the people who know how to sew and you tap into their expertise to see what will work. There’s a story to be told about the makers who made this possible; not just the engineers.

I can’t help but think that the epilogue took a while to figure out. Because as we were talking before, it’s about what these events mean.

I knew I wanted to start with Jeff Bezos’ undersea rover, dredging up one of Apollo 11's rocket engines from the bottom of the Atlantic. I liked the idea of jumping from the moon to the bottom of the ocean as an introduction to the new space race that’s happening right now. The way that the Apollo 11 parts have become relics for a new vision of spaceflight. And at the same time, talking about these objects that were essentially scrap metal offered a good counterpoint, a chance to talk about the sense of apathy that followed Apollo 11. At the time, there were very salient critiques of whether it was even worth it to spend all this money to send twelve men to the moon. I was surprised in my research to find opinion polls from the 1960’s showing that for most of the period of the Apollo program, the majority of Americans polled did not think it was worth the expense. Opinions changed dramatically in July 1969 when everybody was high on the excitement of actually pulling this feat off, but then dwindled again in the months and years after Apollo 11. I thought it was important to illustrate how the fantasy or the nostalgia for this event has evolved over time. We tend to think of it as this shining moment of American triumph, as if it was always like that, but in the 1970’s there was so little thought given to this event, which just a few years before seemed to be the most significant milestone in human history. I think it’s important to remember that our myths ebb and flow over time.

I did cringe at the inclusion of Elon Musk in the epilogue and his sending a car into space. What’s the line about how history repeats itself, first as tragedy then as farce? [laughs]

[laughs] I mentioned in the book that the idea of sending your car into space was the kind of cheeky move that was reflected, not in what the Apollo 11 astronauts did, but in what a lot of the subsequent ones did. Apollo 14 smuggled golfballs. For Apollo 15 it was stack of $2 bills. And there were all sorts of controversies about the astronauts flying things into space so they could resell them when they returned. At one point they smuggled a little statue that they left on the moon. A lot of that is just the human impulse to deviate from the plan. The billionaires leading the new space race feel like an extension of that impulse, for better or worse.

I don’t know if Bezos does this, but Musk definitely gives arguments about why he wants to go to space. They’re not arguments that are easy to hear. One of his main driving reasons to go to Mars is for the survival of the human species. His argument is that, given the trend that our planet is on, with climate change and population growth, if we’re going to make it many more centuries into the future, we need to colonize other planets. That is a grounded argument. But it's grim. As a counterpoint, I love Michael Collins’ memoir of going to the moon, Carrying the Fire. He ends it with a sentiment shared by a lot of astronauts who went to the moon or into outer space. The sense that looking back on Earth from space is transformative. Earth is home. Earth is a gem. Their forays afield have only emphasized for them in starker terms how important it is to take care of what we have already. I think that’s one of the most important lessons to be learned from the brief time in human history when we were going to the moon. That we’ve already got the best thing in the solar system.

Have you started thinking about the next project? Or more broadly how you’re interested in working?

There’s always a ton of ideas. The challenge is figuring out which idea is worth spending years of my life on. That’s the point I’m at right now. I’m having a good time hanging out with my kid and I need to build a bigger chicken coop – life’s pressing problems. I’ve been kicking around an idea for a while about this incredibly widespread determination right now to prepare for the end of the world. And what it means to buy and sell the apocalypse. I think that would be an interesting book to do. For my next project I would like to choose something that isn’t so widely studied and known. I want to track down some overlooked archive and tell a story that isn't already widely known. But then, I know how I work, and I tend to focus on ideas instead of characters and it's always too easy to lose the thread.

Have you ever seen the movie Adaptation? That has become an inadvertent touchstone for me. I love that movie. I love the writing advice that Brian Cox's character gives, even though it's meant as satire. There’s this great scene where Charlie Kaufman is picking the script-writing guru's brain at the bar and he says, “the last act makes a film. You’ve got to wow them at the end.” It's meant as a rejection of all the earnest, complicated, essayistic stuff that Kaufman is struggling with, but I think there's some truth to it. You can get away with a lot if you know how to frame it. Also the idea that Charlie Kaufman’s character is struggling to tell the story about this orchid thief in Florida so he thinks, “start at the beginning of the creation of the Earth.” That’s obviously a little crazy, but I couldn’t help but think about it when I opened the second chapter of my book 4.5 billion years in the past. I mean, clearly dinosaurs are important for telling the story of Apollo 11. [laughs]

So you had it both ways.

I did! Mainly I just wanted to draw some dinosaurs. [laughs]