Reprinted from TCJ #132 (November 1989).

The ’80s began with, and have largely delivered on, the promise of a comics renaissance, the expansion and redefinition of the possibilities of comics art. Though the established newspaper syndicates and mainstream comic book publishers maintained the status quo of complacent commercial success (and exploitation), maverick cartoonists were everywhere. Now, as this perhaps epochal decade ends, we can look back at a body of work that sets new standards for comics, and portends even more ambitious, more challenging, work to come. No survey of this movement would be complete without Lynda J. Barry. Barry got her start around 1979, satirizing relationships and other social issues with acute observation and hilarious delivery. Before long, she developed a narrative style and shifted to remarkably resonant — “accurate” — stories about growing up. “If there’s a last word on childhood, it belongs to Lynda Barry,” wrote Rob Rodi, who reviewed her work in Journal #s 114 and 127.

Born on January 2, 1956, Lynda (“It was originally spelled with an ‘i’ but I changed it to a ‘y’ for the Age of Aquarius”) Jean Barry was raised with her two younger brothers in a working class and racially mixed Seattle neighborhood — which may have inspired her oft-recounted childhood story (alluded to early in the interview) of how she and her friends imagined themselves making a career as pimps. At other times, she aspired to careers as a veterinarian and a stewardess.

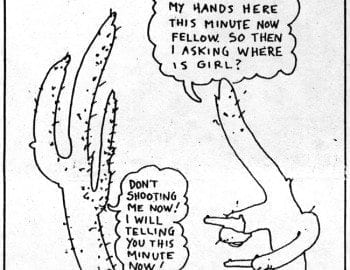

Although she was known as the class cartoonist in grade school, not until she attended Evergreen State College in Washington did she start taking the cartooning side other drawing seriously. Focused on a degree in fine arts, she began drawing comic strips compulsively when her boyfriend left her for another girl: “I couldn’t sleep after that, and I started making comic strips about men and women. The men were cactuses and the women were women, and the cactuses were trying to convince the women to go to bed with them, and the women were constantly thinking it over but finally deciding it wouldn’t be a good idea.” Her schoolmate Matt (Life In Hell) Groening printed her strips, under the title Ernie Pook’s Comeek, in the school paper.

Today, Barry’s strip appears weekly in more than 50 publications, mostly alternative newspapers in large cities. Collections of her work include Girls & Boys (’81), Big Ideas (’83), Everything in the World (’86), The Fun House (’87), and Down the Street (’89). In 1984, she released a coloring book with brief text called Naked Ladies! Naked Ladies! Naked Ladies! She also wrote and drew a full-page color strip examining the everyday pathology of relationships for Esquire.

Continuing her eclectic interests, she released a novel, The Good Times Are Killing Me, last year, and is continuing with the characters from that book in pieces published monthly in Mother Jones (she expects the resultant collection to be published as 1619 East Crowley). The Good Times Are Killing Me, the play performed by Chicago’s City Lit Theatre under the direction of Arnold Aprill, has run continuously since May at the Body Politic Theatre.

If her professional life sounds busy and varied, her home life this past year has been even more hectic. When the first portion of this interview was conducted in September 1988 at the Toronto debut of Comic Book Confidential, Barry had recently moved from Seattle to New York. A few months later, she relocated to Washington, D.C. to be nearer her boyfriend Ira Glass, a producer for National Public Radio. Just a little later, she had reached her fill of D.C, (but not of Ira) and this summer settled in Chicago — near friends and fellow cartoonists Nicole Hollander and Heather McAdams — where the interview was concluded by phone. The interview was conducted, transcribed, and edited by Thom Powers, with a bit of assistance from Greg Baisden.

Inspiration

THOM POWERS: Something that I didn’t realize, which came out when you were talking about Comic Book Confidential, is that you seem not to know a lot about comics history. I wanted to ask you how much you pay attention to other comics.

LYNDA BARRY: I have — I don’t know how to put it — a real idiosyncratic relationship with comic strips. They were the reason I learned how to read. Before I could read, I knew in the Sunday papers where the comic strips were, and I liked to look at the pictures. And I remember not being able to read, and I knew that I was going to be able to read. I had heard people are able to read, and I felt confident that I would learn how to do it myself. So I remember picking the five comic strips that I would read for the rest of my life — it was at the age of 4 or 5 at I was interested in making promises for the rest of my life; I understood the concept of “for the rest of your life.” So I picked these. I picked some bad ones. Some ones I got stuck reading for the rest of my life. Dondi was one of them that thankfully got taken out of the paper, because I had to keep this vow. Brenda Starr was another one. Peanuts was one.

I don’t feel educated on this. For instance, I had to write something for Blab! on how Mad magazine and EC comics affected me, and they didn’t! Except for I like Mad magazine mainly because—who did The Lighter Side of...?

POWERS: Dave Berg.

BARRY: See, that’s an example. Anybody who’s into comics would know it was Dave Berg, right? But all I know is that he draws really good teeth; I was obsessed with the way he drew teeth. “Spy vs. Spy” I really liked. But when I had to sit down and write the Blab! article, I didn’t know anything about EC comics. Nothing. Zip. I learned more about it last night [during a screening of Comic Book Confidential] than I’d ever known. I feel sort of like the poor country cousin from Idaho who comes into the big city. People assume that just because you do comics, you’re going to know something about them.

POWERS: I know Matt Groening is a big fan of a lot of cartoonists.

BARRY: Yeah, well, he has an obsessive, compulsive personality [laughs]. No, Matt’s my best friend. Matt knows everybody. He remembers names. He doesn’t have to say, “That guy who does The Lighter Side of... I know nothing about it, but it turns out that I do them. For a long time, I got really worried because people would ask me what I thought about so-and-so and I didn’t know them. I felt like they’d strip off my stripes, like I’m “Branded.” I thought they’d say, “Well, then you can’t do this if you don’t know these people.”

POWERS: I read in an interview with you that you read Robert Crumb when you were in seventh grade.

BARRY: Yeah. What happened was that I was in history class and somebody slipped Zap #0 onto my desk. It was the first time I realized that you could write about anything. It seems like such an easy idea that you could write about anything, but when you’re a seventh grader, the idea that you could write about, anything, even bad things, about what was happening in real life—I saw stuff in Zap that, even though it wasn’t my life that was represented, it seemed closer to real life than any novel I had read, and anything I’d ever seen in comic strips or in any movie. It seemed just like how people were, and that was so thrilling to me. It really influenced me. I copied Crumb’s drawing. That’s how I learned how to draw; I copied everything.

POWERS: Were you thinking of becoming a painter at that time?

BARRY: No. I was in the seventh grade; I was 12.

POWERS: Were you still thinking of becoming a pimp?

BARRY: I was through the pimping stage. I think I was in a stewardess mode, or a veterinarian. But I did know that I wanted to get more of these comics. Then I learned about hippies. I grew up in a black neighborhood — there weren’t any hippies in my neighborhood. I learned about hippies because I’d won the soundtrack to Hair on the radio. So, then I knew where they were, these comics would be. I learned about head shops. I didn’t know why they were called “head” shops, but I knew I had to go to a head shop where there was a hippie inside, and then get one of these books. Then I was surprised that I was too young to get them. But luckily it was a hippy behind the counter, so he sold these to me.

And then I saw S. Clay Wilson’s work, and I got really upset, see: I thought everything was going to be like Crumb, which has some [explicit] stuff in it, but certainly nobody’s tits are getting cut off. At least, not in the early Crumb work. S. Clay Wilson really scared me, so I kind of drew back from comic strips for a while. In fact, just seeing his face last night in the film was really scary for me. He’s kind of a scary dude, especially when you’re 12. You just don’t want to see those pictures.

But I was really influenced by Crumb; he was a huge influence for me, mainly just because his drawing was so cool and he wrote about anything. The stories — what he actually writes about—never moved me that much. It was the freedom that he had.

POWERS: Then did you continue to look at that stuff through high school?

BARRY: Yeah, but I sort of lost touch with it. What was I drawing? I started actually copying Lautrec’s work and more of the people who were doing graphic stuff during the big French time.

POWERS: In high school?

BARRY: Right, in high school. I kind of moved away from comic strips although, because I could draw comic strips, I always had this certain place socially, like if somebody needed a birthday card. Literally in my school, which was a really rough school, if I walked down the hall with a drawing board with some cartoony drawings on it, then I wouldn’t get beat up. So it was like this talisman. So I kept up with it, but I was never all that good.

POWERS: Where were you seeing Lautrec’s work in high school?

BARRY: In books in the library. You hung out in the library because everybody got beat up, and that was the one place for sure you could rest calmly and not get beat up.

POWERS: You just found that independently?

BARRY: Yeah. If I had gone to a high school where you didn’t get beat up, I don’t know what I’d be doing now. Maybe I would be a veterinarian. It was the violence factor that kept me looking through books.

POWERS: Was it unusual for you to go to college from your neighborhood?

BARRY: Oh, yeah. Nobody did. From my family I was the first person to go. To this day I don’t know ... I ended up transferring out of my really violent high school into a high school that was much more together — because I’m a quarter Filipino, so I was like this Asian transfer student. They were trying to bring the ghetto to the white people, and I was part of that; I was like this hors d’oeuvre, this racial hors d’oeuvre that was served over to this school. So I met all these kids who were talking about college. College was not even a question; everybody was going to go. And I felt like if I didn’t go I would be stuck on 25th Avenue South for the rest of my life. So I ended up going to Evergreen State College, which is where I met Matt [Groening].

POWERS: Is Evergreen in Oregon, or in...

BARRY: Washington. And the high school I transferred to was where [Charles] Bums was going, too. He was a year older than me. We had the same art teacher. I used to see him around. Then we all ended up at Evergreen together.

Accidence

POWERS: Then by the end of college, you were dabbling in cartooning.

BARRY: Yeah. I was doing it, and I’ve never stopped since then. I told this story in front of a crowd, so you know it, right? I got dumped by my hippy boyfriend and then started drawing. Then the stuff just started getting printed by accident.

POWERS: Matt started printing it?

BARRY: Matt and another guy named John Keister, who worked at another newspaper, the University of Washington’s newspaper. He’s the one who actually started the whole thing; they were printed under the name Ernie Pook’s Comics and people really liked them. So he called me up and had to admit that he had been printing them without asking me, and that they needed some more.

POWERS: When you left college, then, did you decide to make a career of it?

BARRY: No, I didn’t. I was going to be a painter no matter what. But I knew I could draw, and I liked writing. I especially liked writing little tiny, dinky stories — midget stories — so I wanted to keep doing it because it satisfied me. Again, I never have been one of these real career-minded people. I guess I am a hippy in a way; I just sort of flow with everything. I’m still flowing, man. All the lyrics from Hair were absorbed as my deep, intense philosophy. It all just really happened by accident. I was selling popcorn, and my comic strips were being printed in the local paper for — I think it was $5 a week. Bob Roth called me from the Chicago Reader as the result of an article Matt wrote about hip West Coast artists — he threw me in just because he was a buddy, right? And then Bob Roth who runs the Chicago Reader called and wanted to see my comic strips, and I didn’t have any originals. I didn’t know anything about originals, that you don’t give them to newspapers because newspapers lose them. So I had to draw a whole set that night and Federal Express them. So I did, and he started printing them, and he paid $80 a week, and I could live off of that. And because he’s with this newspaper association, the other papers started picking it up. So it was luck. Sheer luck.

POWERS: What about Matt? Didn’t he get into it simultaneously?

BARRY: He got into the Los Angeles Reader, For a long time the Los Angeles Reader wouldn’t print me, and the Chicago Reader wouldn’t print Matt even though they’re sister publications. So we both worked on the publishers and the editors to get each other in. It was really funny: when we got into each others’ papers, everything sort of took off for both of us. There are all these moments in both of our careers where there’s this funny decision that was made or this funny favor that we did for each other. It’s amazing to me that we both do this when I think of just meeting him when we were 19. I think of his strip as sort of my brother’s strip in a way.

POWERS: I’ve noticed that in other interviews and in The Good Times Are Killing Me, Nicole Hollander’s name comes up a lot. What is your relationship with her?

BARRY: Nicole and I are really good friends. She’s great. She’s amazingly the only daily cartoonist I’m friends with. I like to call her up, and mostly our conversations are like how hard our job is, how lonely we are, how bad it is to stay in all day drawing cartoons, that we never go out, how we both work at home. But Ira [Glass] came up with this idea: a 976 number for cartoonists who are inking so that they can call each other. Like when I have to ink or when Matt has to ink, we always talk on the phone. We talk for, like, two or three hours.

POWERS: Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez do, too.

BARRY: Really? Do they? There’s nothing else to do. You go crazy. So Nicole and I—in fact, I just had a really long conversation with [Mark Alan] Stamaty. It was like three hours. Same thing: inking.

POWERS: Did you just meet him recently?

BARRY: I met Stamaty about eight years ago, and I see him on and off, but this last conversation—when we realized that we lived in the same area code and it was going to be cheap to call each other. We just knew it was going to be the ultimate friendship, based on economics.

We’ll never go out. I asked him if he wanted to go see a movie, and it’s sort of like that’s three dimensional activity for both of us, which is hard to fathom. We thought about it. We had to discuss it: that means we’ll have to take money out of our wallets, make small talk, look at each other. If you think about it, for a cartoonist, the phone is like the ultimate social contact.

POWERS: How did you meet Nicole?

BARRY: I met Nicole on a book tour where we were both asked to talk about how we’re like these men-hating cartoonists [laughter] — how we hate men and think we’re the queens of the world. We hit it off. I really love her. I like what she’s doing a lot. The other person who I think is real good, and who I’d like to hang out a little bit more with is Roz Chast. She’s another person I think is interesting. It’s funny that her name isn’t brought up more often.

POWERS: Yeah. I think it’s sort of The New Yorker ghetto. And you’re in the ‘‘Alternative Weekly’’ ghetto.

BARRY: What the hell! Yeah, I think it’s so funny. There’s this thing I quote a lot in the beginning to Diane Arbus’ book. She talks about going to this dance where it’s all handicapped people. She dances with this man who says, “Well, you know, the cerebral palsy’s — we hate the muscular dystrophy people, and we both hate the retarded” [laughter]. And that’s how I feel. In cartooning there is this — I don’t get it.

POWERS: I don’t know that it’s hate between them. It’s when they’re written about ...

BARRY: There is still something: the super-heroes versus what I do. It reminds of in prison, in the smallest possible space, there’ll still be hierarchies that are established. I think that we should have cartoonist wrestling.

Cartoonists’ Heaven and Naked Ladies

POWERS: You grew up in Seattle and lived just about all your life there.

BARRY: Yeah. Up until June 1st [1988].

POWERS: Right.

BARRY: I lived in France. I’ve lived in different places, but mainly Seattle. I’ve always called it home.

POWERS: Why the move?

BARRY: I’m getting divorced and I had to leave. That’s the truth of the matter. I’ve tried to figure out in interviews what else to say, like, “Oh, I just felt like it was time for a change.” Basically, it was an ejector button that was hit, and I landed in New York. It turns out to be fine: I know a lot of people there; I have a dinky little apartment; and I’m just careful to step over the syringes as I walk out.

POWERS: Is there a different quality of the life in New York?

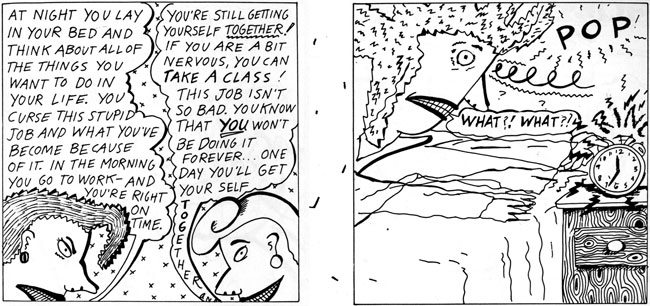

BARRY: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yup, yup, let me be the first to tell ya. Yeah. Jules Feiffer’s my neighbor, though. I like that, the neighborhood. I have more friends in New York than I had in Seattle, but in Seattle I had a lawn. In Seattle I had grass; I could drive my car. To get in a car right now driven by somebody who isn’t a cab driver is a fantastic experience for me. You know how a lot of people have digital clocks on their dash boards? I always think that’s how much I have to pay. I drive with Ira, and I’m thinking, “12 bucks! Shit!” [laughter] It’s affected my work: in Seattle, I had a studio separate from where I lived, and I liked that a lot better. I just don’t like this idea that my drawing table is always up there speaking to me — You’re late for your deadline! You must come work!”

POWERS: Do you pine for Seattle?

BARRY: Yeah. I cry! I don’t pine; I weep. It’s messy. It’s not pretty tears, either. It’s bawling. Yeah, I miss Seattle, but I know it was time to go. I feel sort of like — you know those certain guys who graduated from high school but sort of never left? Or college? You know, the ones who went to college in a small town and hung around a little too long? I’m like one of those guys: I was in danger of being one of those really scary people who just wouldn’t leave. So I’m glad I left, but I’m a real baby about it. I miss my car. It had a graphic equalizer. I miss it. I miss my house. I had a house with steps. Seattle is the cartoonists’ heaven because it does rain, so you stay in all the time.