From The Comics Journal #191 (November 1996)

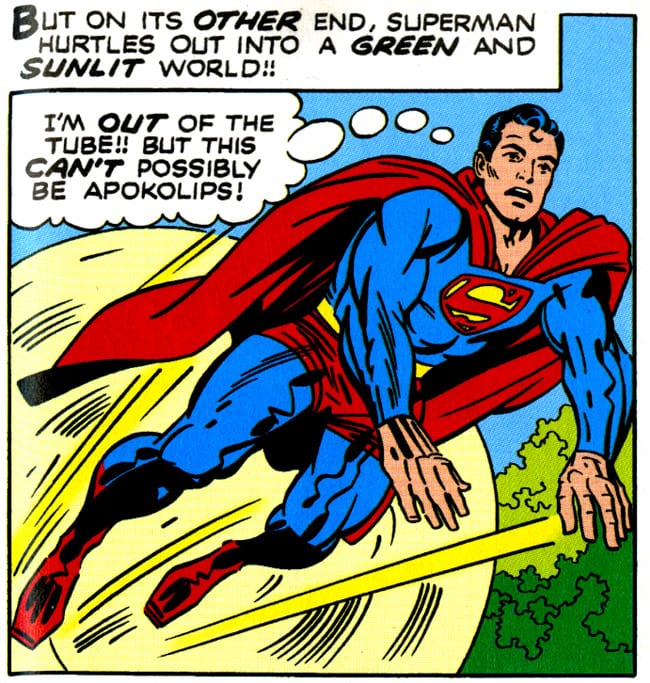

Carmine Infantino encountered a barrage of criticism last year in the pages of The Comics Buyer’s Guide after he defended a decision he made while he was the editorial director at DC Comics in 1971 that was called into question by Mark Evanier. During Jack Kirby’s stint on DCs Jimmy Olsen comic, Infantino authorized re-drawing Superman’s head as drawn by Kirby, claiming that it was necessary to preserve the value of the licensed Superman characters, and noting that Kirby himself had no qualms with DCs decision to change his work.

Infantino claims that CBG and specifically editor Maggie Thompson have failed to allow the controversy to be aired fairly in CBG’s pages, demonstrating partisanship in supporting the paper’s columnist by giving preferential treatment to Evanier’s side while suppressing parts of and delaying publication of letters defending Infantino by as much as six months. Infantino also took umbrage with Evanier for trying to persuade Mark Hanerfeld, who wrote a letter defending Infantino, to retract his letter before it was published sans a paragraph (which Evanier suggested to Thompson be removed) that claimed Evanier had spread allegations about Infantino misrepresenting the sales figures for Kirby’s DC books (although that rumor had never in fact been printed).

The controversy was launched in Mark Evanier’s “Point of View” column in #1121 on May 12, 1995, when Evanier called Infantino’s decision the “the classic example” of people exercising authority simply to demonstrate their power. Although the retouching of the heads was done under the guise of consistency, Evanier stated, “the sad truth was that the office then had such a hatred of “Marvel-style” art that they could not cope with a “Marvelized” version of their sacred Superman, nor the possibility that it might outsell what they saw as the company created version.”

He also related a quote from the late artist Mike Sekowsky, who was editing for DC at the same time as Infantino. Evanier reported that Sekowsky said that Infantino felt he was “scoring some kind of victory over Marvel with this, somehow proving to the world that Marvel’s star artist wasn’t good enough to draw a DC star character, or that the DC editorial department could improve on Marvel’s best.” (Infantino called this accusation “garbage” and questioned Evanier’s use of “dead people for quotes.”)

Kirby’s heads couldn’t stand, Infantino said, because they were different from the standard versions of the characters, which would have diluted their value. He noted that the decision had legal ramifications; failure to protect a trademarked property might result in losing the rights to it. For an analogy, Infantino suggested that if Kirby were to be hired by Walt Disney, no one would find it odd if the studio altered Kirby’s version of Mickey Mouse to make it conform to the standard characteristics of the character.

Infantino responded strongly to Evanier’s column in the following letter, which appeared in CBG #1128:

I would like to respond to the pointless ramblings of one Mark Evanier in your May 12 issue in which he denigrates the editors and publishers for their attempts to protect the integrity of valuable comic book properties.

Specifically, he laments the fact that other editors and I required that Jack Kirby’s work be corrected to conform to those established characters be was assigned to draw. It is an ancient piece of business but it seems Evanier has a habit of digging such matters and twisting them into some sick agenda to revise the fact and indeed to fly in the face of common sense.

Whatever attachment Evanier has for the late Mr. Kirby does not give him the right to condemn the efforts of management, which expects an artist to deliver what he promised to deliver when he accepted the assignment — in my case, as publisher of DC likenesses of Jimmy Olsen and Superman.

For the record, I was not happy about having Kirby’s version redrawn by our staff. It was costly, time consuming and embarrassing, but I took the blame. The sales of the Kirby issues plummeted and we hastened to revert to our traditional artists. The sales soon recovered, proving my decision was correct. Evanier’s reckless quote, attributed to a person conveniently dead, said that “because Carmine Infantino found Marvel’s best artist not good enough for DC, Infantino was scoring some sort of victory with this.”

This is so idiotic and juvenile that I wonder how any person with a minimum IQ could believe it.

Another thing: If you adore Kirby so much why do you dump on his reputation by revealing that both Marvel and DC bad to redraw his work? I am aware that you also spread the notion that I canceled some of Mr. Kirby’s books despite the fact that they were profitable. This is not fact: it’s fantasy. No publisher in his right mind would ever drop a profitable publication. For your information, these decisions are dictated by the distributor based on actual sales figures. Your ignorance is abysmal.

The truth is, despite my personal admiration for Jack Kirby’s raw pencilling, he was successful only when he worked under Joe Simon or Stan Lee. The only blockbuster he was associated with for DC was the return of The Sandman, and Joe Simon wrote that one and laid out the entire comic book. Get a life, Mr. Evanier!

Although he didn’t include it in his letter to CBG, Infantino also mentioned to the Journal that Kirby himself was told well in advance that his work was to be altered.

“I never did anything without talking to [Kirby],” Infantino said. “I said, ‘Jack, we’ve got a business problem. The heads are not like the accepted Superman heads.’ He didn’t see any problem with that. He said, ‘Absolutely. Fix ’em.’ It was no big deal.”

At the time of Infantino’s duration as publisher at DC, Infantino said, Kirby had grown tired of the poor treatment he was receiving from Marvel. The company never gave him appropriate compensation or credit for his role in creating the Marvel universe, and withheld his original artwork from him for years. Kirby wanted to make the switch over to DC, but there was one hitch; the creator was involved in a legal dispute with DC editor Jack Schiff, who had worked with Kirby for a while on Skymasters, a newspaper strip.

For whatever reason, Kirby took over the sole production of the Skymasters strip, and as a result, many people at DC were hesitant to hire Kirby because they felt he had wronged Schiff. Infantino maintains that he was the one who convinced the higher-ups at DC to sign Kirby on, and that it took him a great deal of effort to persuade them to do it.

Infantino said that he explained to Kirby when he came aboard DC that some of his versions of the characters from Superman would have to be modified in order to fit the pre-existing specifications. Kirby, Infantino said, didn’t have a problem with having his artwork altered, and viewed it as simply a matter of business.

After his response to Evanier’s column, letters poured in to CBG denouncing Infantino, from Frank Miller — who said that Infantino had denigrated Kirby’s work — to Bill Mumy, who said in #1136 that “having recently read Infantino’s letter to CBG kicking the ghost of Jack Kirby,” he could no longer enjoy Infantino’s work. Mumy added that Infantino’s justification of his decision did not ring true. And Miller said of Infantino’s “bitter attack” on Evanier that “once again, the old machine coughs out bad old oil.”

Richard Kyle wrote in #1134 that Infantino’s letter “demonstrates succinctly why he was a failure as an editor and as a publisher.” He neither respected nor understood his contributors, Kyle said, and accused Infantino of displaying great contempt for Kirby by forcing him to conform to DC’s “bland, corny” house style. “Because of Infantino’s ineptitude,” Kyle wrote, “a brilliant creator was denied the opportunity of his life.” And Jo Duffy wrote in #1132 that “Carmine’s judgment or his memory of what transpired must be seriously impaired,” in reference to Infantino’s statements about the sales on Jimmy Olsen. Duffy maintained that because the devices for determining newsstand sales didn’t reach publishers for months after books were shipped, his justification for taking Kirby off the book was invalid and his “whining, crying, and name-calling… [is] contemptible.”

In addition, Randy Buccini, Event Comics’ Kim “Howard” Johnson, and the University of Illinois’ Dr. Michael A. Pemberton (who said he would have been “mortified” to have authored such a “nasty, sniping” letter) also weighed in against Infantino’s response. Not everyone that wrote in came out against Infantino, however. Billy Harris cautioned against the “canonization” of Kirby, which denigrated his actual accomplishments (#1134). In #1147, Chris Zickrick stated that Evanier had “crossed the line,” and that the use of his column “to smear Infantino’s name by using the biggest and most legendary name in comics was tacky.” And John Coates provided the last letter (to date) on the subject in #1166 when he stated that Infantino’s decision was well within his rights as an editor. Coates’ letter, which appeared on March 22, 1996, puts the time span of the controversy at about 10 months from the date of Evanier’s initial column.

The longest statement in support of Infantino came from Mark Hanerfeld, a close friend of Infantino’s and the assistant editor to Kirby during his defection to DC. Hanerfeld wrote a letter to CBG defending Infantino’s reasoning in changing Kirby’s characters and emphasizing Kirby’s approval. But although Hanerfeld sent the letter on July 22, 1995, during the height of the controversy in CBG’s letters pages, CBG didn’t print it until the end of January, 1996. Only Duffy’s brief second retort in #1163 and Coates’ letter appeared after the printing of Hanerfeld’s letter.

And when the letter was finally printed, Hanerfeld said, a crucial portion of the letter was edited out. The paragraph in question related that Evanier had spread a rumor around about Infantino keeping two sets of sales books — one real, one fake — at DC, without ever identifying the “top executive” at DC whom he said gave him the information. The implication of the rumor was that Infantino had shown Kirby fake sales figures of Jimmy Olsen to justify taking him off the book.

“You censored, bowdlerized, expurgated, perhaps even exorcised the intent of that communication,” wrote Hanerfeld in a letter to CBG editor Maggie Thompson on Feb. 3, 1996, shortly after the edited version of his letter was printed. Hanerfeld said that this was despite a Jan. 21 phone conversation he had with Thompson before the letter was printed in which she agreed to print the letter in its entirety.

He then asked Thompson to publish a new paragraph that he had re-written which he felt “would restore the meaning of the intent” of his original letter:

I think that the crux of all this feud began a few years ago when you began the rumor that DC comics bad given Kirby false sales numbers on the books he did for them. You stated that DC kept a second false book that they showed to artists (and presumably to writers as well) and that they had given those false results to Jack. But you never gave that name. I asked you, and you said you couldn’t. Unfortunately, you’ve kept your word. You and the people around you have gotten to believe that unsubstantiated “truth” as gospel. You’ve never looked around for other accounts of your “truth.” Well, I have; and after many years and after many inquiries to varied professionals, from editors to accountants to even production people, none have substantiated that “truth.”

CBG declined to print Hanerfeld’s restoration. Thompson responded to Hanerfeld via letter that “I had assumed from your question on January 21 that you wanted to know whether we would not treat your letter as excerpted material — not that we would not edit it.” She went on to state that CBG edits every letter that comes in, making deletions for material based on the following criteria:

- Material that is so long it usurps more than its proper share of the letters column

- Material that is gratuitously insulting

- Material that is problematically speculative

- Material that perpetuates negative gossip

- Material that uses terms or pictures that are not appropriate for the fact that CBG goes into some grade-school environments.

The accusations made against Infantino regarding the false set of sales figures, Thompson said, never appeared in CBG, and that for Hanerfeld to speculate on Evanier’s motivations in such a manner would go against the CBG policy of refraining from printing rumors.

Hanerfeld said that Thompson reiterated this same reasoning over the phone to him when she declined to print the following additional letter that he sent to CBG dated Feb. 23, 1996:

This is in response to Jo Duffy’s letter that appeared in CBG #1163, which in turn was in response to my letter that appeared in issue #1161.

There was no imagination used in my forwarding of the facts that I’ve put into the writing of my letter. I was there, and I reported the facts as I remember them.

And by the way, I’m not ill, just disabled. In fact, I lost the ability to plot stories with the last stroke.

You inferred that I “cast unjust and ungentlemanly asperison’s [sic] on Evanier’s veracity.” “Ungentlemanly” — NO WAY! In the main, I posed facts and figures for Mark’s pondering and meditating his attitude towards Carmine. And, as far as “unjust” goes… well, that’s up to the opinions of those people who have delved deeply in the subject.

What “inherent illogic of Carmine’s act” is there to have Jack Kirby’s version of the Superman characters’ heads change? Is it logical to produce comics that are intended to sell to fans because it’s done by Jack Kirby? The heck with all those long-time Superman fans. It’s done by KIRBY! You’re talking about fanzine fare. Jack was a professional comics editor/writer/artist and onetime co-publisher (Crestwood was before your time). He produced those comic books to be sold on the newsstand. (He, several years later, produced a number of magazines for Pacific Comics that were intended for his fan-following, to be sold on the Direct-Sales only stands.)

After explaining that Kirby had agreed to the changes on his artwork, Hanerfeld wrote:

I assume this and the next paragraph will be censored out by the CBG staff, but I must put before you the following facts:

It seems to me that Mark Evanier has had his hand in the editorship of CBG far further than they will admit. You’re [sic] last letter (the one that this is written in response) saw print far sooner then [sic] a letter normally sees print in the CBG. Only two issues between both of our letters. Suspicious. Over the phone, last Friday (February 16th), Maggie recited from a letter she had written to me, one of the many reasons why they exorcised a crucial part of that long-delayed (it was initially mailed July 22, 1995) letter, as well as a following letter which they also refused to print. I have enclosed a copy of that letter with this letter. (She read the letter to me from her computer screen; she promised to send copies of that letter to myself and to Carmine Infantino, post haste; we’re still waiting for them). One of the reasons she cited was the length of my letter; that it was hard for them to find that much room for more than six months. Yet they found the space to print the letter from Robert Beerbohm (the letter that directly precedes your letter in the lettercol) which covers the Mike Tiefenbacher article about Marvel’s circulation history. Tiefenbacher’s article appeared less than two months previously. His letter took four and a half (approximately) columns to print, while my letter took four and three-quarters (approximately) columns to print. And isn’t that somewhat suspicious.

And isn’t it strange that when Mark Evanier gave me a call upon first reading the letter I sent him, be spent a good deal of the conversation trying to persuade me from having the letter printed in the CBG. He had just returned from the 1995 San Diego Con, and in his spiel he told me that Richard Kyle had a letter in the next issue of the CBG, supporting his stance. I find it very suspicious that he had specific knowledge of what will be printed in future issues of CBG’s lettercol. It seems that Mark had contacted many of his friends and coterie and asked them in helping to support his position. Including Bill Mumy,“the guy who produces the Jack Kirby fanzine (whose name still eludes me),” and you. Please correct me, if I’m incorrect, as to my conclusion that your response to Carmine Infantino’s letter was somehow prompted by Mr. Evanier.

It seems to me that much, if not all, of your information about this controversy comes almost exclusively from Mark Evanier. You’ve only heard his version. Why don’t YOU take the initiative, and find out the truth on your own. Contact those who were there. Sure, Sol Harrison, Murray Boltinoff, and others have died. But Jack Adler, Joe Kubert, Joe Orlando, Jack Schiff, Julie Schwartz, Arthur Gutowitz (the company’s then accountant), Gerda Gattell, former staff letterers, colorists, production people, are still around. Why don’t you track down these people and find out the facts for yourself? Why don’t you call Roz Kirby and ask her about the relationship between Jack and Carmine, and what the real situation was back then? And ask her the humorous anecdote about Carmine vis a vis Gefilte Fish at a Passover Meal at the Kirby California home.

Infantino also responded to Thompson’s reply, which was sent to him by Hanerfeld, with a letter of his own. Citing the CBG policy which declares insulting, speculative, and gossipy material to be unpublishable, Infantino asked, “Then explain why you printed a letter from John Morrow, in an issue dated July 21, 1995 (#1131) in which he stated that he corresponded with at least ten unnamed subscribers who had ‘firsthand knowledge’ of hearing that I made negative comments about Jack Kirby. Further, he related that one of those subscribers, whom he doesn’t name, claimed that he was in my class [at the School of Visual Arts] and I did nothing but knock Kirby.”

Infantino added that none of his former students that he had talked to could recall Infantino ever making such comments about Kirby in his class, and that he felt CBG was contradicting their letters’ “manifesto” by printing such a letter.

Although the Journal asked Maggie Thompson to explain her apparently selective use of CBG editorial policy, she declined to comment, saying that she preferred not to discuss in-house matters in public.

However, Evanier agreed to respond point by point to the allegations levied at him by Hanerfeld and Infantino. Evanier confirmed that he told Hanerfeld about the rumor to the effect that Infantino kept two sets of books, but that the only person he asked about it was Hanerfeld, who then informed Infantino that he was “spreading the story” around. And furthermore, Evanier added, he doesn’t even believe the rumor himself; he said he believes that artists weren’t actually shown the sales figures in the first place, which would eliminate the necessity for a phony version.

“What we have here is a situation where someone is denying a story that no one really charged,” Evanier said, noting that he never said it in print or at a convention, and that the incident Hanerfeld refers to happened back in 1977.

Responding to Infantino and Hanerfeld’s accusation that Evanier tried to pressure Hanerfeld into rescinding his letter before CBG published it, Evanier acknowledged that when Hanerfeld sent him a copy of his first letter to CBG, Evanier and Marv Wolfman, a mutual friend, tried to persuade Hanerfeld not to print it at all. The reason he tried to talk Hanerfeld out of printing the letter, Evanier said, was because he felt Hanerfeld “had misinterpreted things” and that to deny the “rumor” about the false set of books would have lent more credence to it when the “rumor” had never appeared anywhere in print and had only circulated “for about 10 minutes, 20 years ago,” Evanier said. “He was prolonging an issue that no one was talking about.” Evanier acknowledged that he suggested to Thompson that the paragraph in question be deleted, for the same reason that Thompson told Hanerfeld — the rumor had never appeared in print in CBG.

As for whether or not he believed that Infantino had taken Kirby off his slot on Jimmy Olsen even though it was selling well, he said, “I don’t know. At that time you’d hear one [sales figure] on Monday and another one on Wednesday.”

He added that although he believes Infantino harbors a grudge against Kirby, he was not made aware of it until Infantino sent him a “nasty letter” which made disparaging remarks about Kirby in response to the “Point of View” column.

As for Hanerfeld’s suspicions about Evanier’s knowledge of the future letters to be printed in CBG, Evanier stated that Kyle told him personally that he had sent in a letter for publication in CBG, and he denied the notion that he had solicited support from any of those who chastised Infantino in the letters section. In fact, Evanier said, he actually told a few people who contacted him with the intent of writing scathing replies to Hanerfeld not to do so.

And in regards to the quote from Sekowsky that accused Infantino of trying to score a victory over Marvel by changing Kirby’s work, Evanier said, “I just presented an opinion that I think a lot of people held at the time.” And no one other than Sekowsky told him as such in a manner he could attribute.

When the Journal asked Evanier if he thought CBG’s treatment of Hanerfeld was fair, he said “I don’t even have an opinion on that,” noting that “I think CBG has a right not to print whatever they feel like just like any other publisher.” He added that at the time Hanerfeld’s letter was printed, CBG had a large backlog of letters — many of which were printed with the same sort of qualifier that appeared with Hanerfeld’s, explaining that the letter had been received a long time ago, and had been delayed due in part to its length. But he emphasized that such questions about the timing and fairness of the way Hanerfeld’s letter was published were Thompson’s domain, not his.

Evanier was also willing to expand on his original criticism of Infantino. He said that to put Kirby on a title where his heads would have to be changed was, in his opinion, a mistake from the beginning. “Kirby didn’t enjoy doing someone else’s characters at any time in his career,” Evanier said. While Kirby said in his interview with the Journal in #134 that he requested to draw Jimmy Olsen, Evanier — who was Kirby’s assistant on his Fourth World series — said that Kirby chose the book because he didn’t want to displace a regular artist, and took Jimmy Olsen because the slot was open.

“I think Infantino has a problem here in understanding the criticism,” Evanier said. “There’s a difference between saying that he didn’t have the right to do it and saying it wasn’t a good idea… I think he’s taking this way too seriously.”

In conclusion, Evanier said that he hoped the matter, which he described as trivial, could finally be put aside.