Today we say goodbye to Leslie Stein, with her fifth contribution to the Cartoonist's Diary column. We also present Ken Parille's newest GRID, in which he evaluates many of the comics of 2011, including Habibi, Holy Terror, The Death-Ray, and many others.

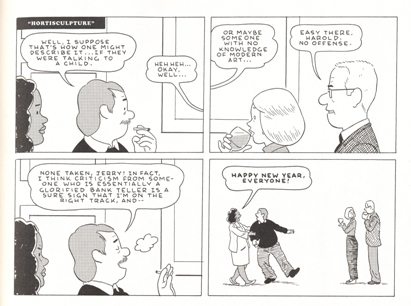

One of the comics Parille discusses is Adrian Tomine's Optic Nerve 12, which I happened to finally read just a few days ago, though I purchased it the day of its release. (Not until this past year, after making a sincere effort to read as many comics of interest as possible, have I realized just how many solid comics there actually are being published, and how easy it is to fall behind. I read comics every day, and still haven't gotten to several of the books on Parille's list, for example.) Anyway, this is a very strong issue of Optic Nerve, which I enjoyed enough that it makes me want to go back and re-examine some of his earlier work—his earliest minicomics were raw and very funny, but somewhere along the way, his comics stopped clicking with me on a regular basis. Despite Tomine's obvious artistic command, his characters, plots, and situations seemed so low-stakes, yet were apparently taken so seriously, that I found it hard to relate to what was going on. I wonder now, after enjoying this last issue so much, as well as large portions of Shortcomings, if I was simply misreading him—the story I like best here, "Hortisculpture", is also sort of slight, but the character interplay and dramatic situations are handled so lightly, and his storytelling displays a subtlety so far beyond most of what's being published at the current moment, that the parts end up seeming strong enough to redeem the whole. (Of course, I've only read it once so far, and new facets may reveal themselves on a second or third go-round.)

Parille makes it a point in his column to focus on the key formal aspect of "Hortisculpture": the way its scenes are planned to resemble individual episodes of a daily newspaper strip. This is becoming an increasingly popular strategy -- Clowes did something similar in Wilson, Tim Hensley in Wally Gropius, Seth, Ivan Brunetti, David Heatley, etc. -- and it produces an interesting effect. In Wilson, portraying the title character's life in discreet strips not only allowed Clowes a formal excuse to experiment with different drawing styles at appropriate moments, but also served to recast the often disturbing incidents of Wilson's life as temporary and humorous situations. A character being sentenced to prison reads differently in the context of a long-running comic strip than it does as the middle section of a more traditional graphic novel. (Is it too early to apply the term "traditional" to graphic novels?) In Wally Gropius, it makes the often perverse goings-on even more unsettling. And in "Hortisculpture" it somehow manages to add a melancholy tone to what is an essential comedic storyline -- exploiting not only the reader's natural inclination to fill in the narrative gaps "between the gutters," but also his or her tendency (trained by exposure to so many decades-long strips) to imaginatively extend a comic strip's storyline in all directions. A more traditionally organized story would seem more settled, more complete.

These effects are everywhere in comics these days, and not always created consciously. In their most recent collected editions, Prince Valiant and Gasoline Alley and Little Nemo read differently than they used to--and we see their creators differently because of it. Frank King is revealed as an early graphic novelist; for the first time in decades, readers can begin to experience the wonders inspired by properly printed strips from Foster and McCay, published at or close to their originally intended size.

Of course, we are still not reading these strips as the original readers did. Simply being collected into books changes the strips' context dramatically. When Fantagraphics divides the constantly reprinted EC stories into artist-specific books later this year, it will undoubtedly similarly change our understanding of the work, whether we notice it consciously or not. Sometimes reading the lavish new collections of Terry and the Pirates or Popeye or Dick Tracy or Little Orphan Annie, I wonder what it would have been like to experience these strips as they were published, one daily installment at a time. All of these great proclaimed masterpieces were not intended to be read in large gulps, but in daily sips over decades. Barring accident or disease, I've probably got five or so decades of good vision left, so if I want to try out one of our classics the "real way," I need to get started soon.