Joe Giella is one of the creators synonymous with the Silver Age of comics. In his more than seven decade career, Giella was primarily an inker, working extensively with Carmine Infantino, Gil Kane, Sheldon Moldoff, and others. He worked at Timely, Hillman, and other publishers in addition to advertising work and comic strips, but he spent much of his career at DC Comics where he drew every major character and worked on some of the period’s most iconic covers.

He drew the Batman newspaper strip for a few years, which were reprinted in the recent collections from the Library of American Comics. Giella also assisted his friends Sy Barry on The Phantom, and Dan Barry on Flash Gordon for many years. In 1991 he took over drawing the daily comic strip Mary Worth, working first with writer John Saunders and then Karen Moy, until Giella retired in 2016 at the age of 88.

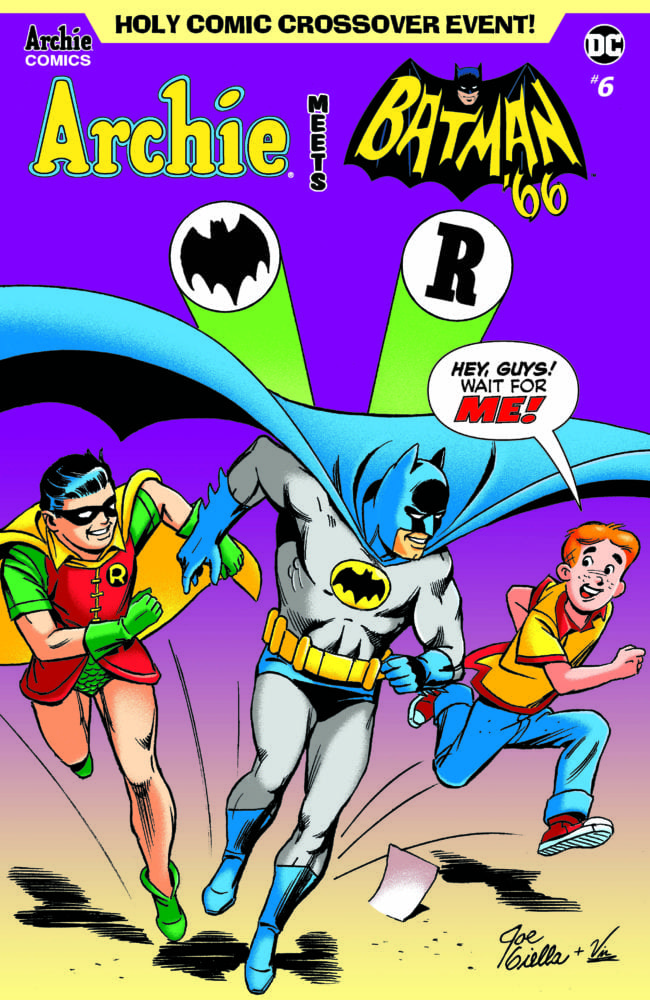

Since then Giella has been taking limited commissions and doing the occasional project like the recent variant cover for Archie Meets Batman ’66 #6. Giella is the recipient of many awards including an Inkpot, he’s a member of the Inkwells Joe Sinnott Hall of Fame and was given the Hero Initiative Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2016 Harvey Awards.

Thanks to Jeffrey Hartnett for helping to arrange our conversation.

You studied at the School of Industrial Art in New York, do I have that right?

You studied at the School of Industrial Art in New York, do I have that right?

Yes. Academically the School of Industrial Arts left a lot to be desired, but if you wanted to work in the arts like photography, figure drawing, that was the place to go. They had great teachers there. We learned a lot. I know friends – a few passed away now – that I met at the school like Dan Barry and Sy Barry. I really enjoyed it.

Sy Barry is still around, though, right?

He’s still around. He’s my buddy. There’s still one or two of us. I’m ninety and sometimes when I think about it I get worried. [laughs] But I feel great.

Did you grow up in New York?

In Astoria, Queens. I grew up on the same block as Tony Bennett. He was a friend of mine. He also is a pretty good artist and also attended the School of Industrial Art.

You started working in comics as a teenager. When and why did you start?

They ask me this every time I go to a convention and I’m required to go on a panel. Invariably they ask me the same questions, how did you start and so forth. At that time things were really rough. I don’t remember too much of the problems my dad had, but he was having problems making the house payments. As the first son in an Italian family, I had to go to work. All my brothers are educated, but I’m lucky I had high school. I wanted to get into comics so bad because I loved to draw. I was sixteen and a half and I pounded the sidewalks in New York looking for work. I got rejected because I didn’t have experience. Ed Cronin was an editor at Hillman Periodicals, and he gave me an assignment in Punch and Judy Comics. “Captain Codfish.” This was in 1946. He was going to give me another job, but I’d have to wait three or four weeks before he’d give me another script. Now I had a printed piece so I could show editors like Stan Lee. That’s how I got started. But even with my salary we still couldn’t save the house. My dad had to convert the one family house into a two family house to keep going. Times were tough then. Fans know this story but they keep asking me to tell it. They also always ask me to mention that incident where Stan Lee gave me the first job to try out. You’ve heard about this?

This is the story where you got an inking job and you left the Mike Sekowsky pencilled pages on the train?

One woman asked me about this the last time I was on a panel and I said, you fans are never going to let me forget this. [laughs] After seeing my portfolio, Stan Lee asked me to ink and letter some Mike Sekowsky pages as a tryout. I got off the IRT in Ditmars Blvd. It was the last stop so the train went back to Manhattan. I chased after it, but, well, nobody slept in my house that night. When I told Stan, he was furious, but Mike Sekowsky came to my defense and provided me with a few more pages. Stan liked what I did on the second job that he gave me. We never retrieved the first one. He put me in the bullpen where I did a little of everything. A little pencilling, inking, coloring, lettering, touch ups, corrections – whatever they asked you to do. It was a great experience. They should have that today. I worked at Timely Comics for about three years, from 1946 to around 1949, and then I went over to DC Comics in 1949. I went over to DC Comics to get involved in more than just touch up work and I worked with DC Comics for 45 years.

You worked for C.C. Beck’s studio for a little while. Was that before you started at Timely?

That was before. It didn’t last long. Most of the fellows who worked with me there wound up working at Timely Comics and someone else took our place. I worked on Captain Marvel. My assignment there was corrections and background work and whatever they asked you to do. It was very similar to the bullpen job at Timely Comics. I didn’t have the experience to do an entire story when I worked at Beck and Constanza.

I’ve heard from other artists who started then or afterwards and they would work as an apprentice essentially when they started out drawing backgrounds and inking and doing corrections and whatever else was needed.

I can’t think of a better experience for a young artist. Because you do a little of everything. Then you’re good enough to do the actual drawing or work from a script. When it came to the straight adventure comics, you needed experience. I had fellows like Syd Shores at Timely Comics. He was drawing Captain America at the time and he really helped me out. He knew what a young guy goes through and he answered every question I had and really took his time. Dan Barry did the same with me. They recognized something in my work and helped me. I was just so eager for information and wide eyed and I couldn’t wait to get to work and learn.

As you mentioned, you worked at DC Comics regularly for 45 years. And you were doing mostly inking but not exclusively, and you didn’t have a signature character or genre like some artists, you did everything.

As you mentioned, you worked at DC Comics regularly for 45 years. And you were doing mostly inking but not exclusively, and you didn’t have a signature character or genre like some artists, you did everything.

I worked on all the characters – Superman, Hopalong Cassidy, The Flash, Batman. While I was at DC Comics I did mostly inking because I could ink faster than I could pencil. A lot of other fellows at the time went to inking for monetary reasons like Dick Giordano and Frank Giacoia and Joe Sinnott. When I was offered the Batman strip I thought they just wanted me to ink it but the editor said no we want you to pencil and ink it. DC had seen samples of my pencilling but I shied away from that because I had to bring home money. I remember one time I was on a panel with Joe Sinnott and Jerry Robinson at the Jacob Javits Center. The first question was directed to Joe and it was, how did you guys survive with that horrible page rate? It was like six dollars a page. Joe answered the question and my wife was in the front row with her hand on her forehead as she remembered those days.

Drawing the Batman syndicated strip was the rare occasion you pencilled and inked. You worked on it for almost three years.

Drawing dailies and Sundays is very tough and it’s too much for one guy. Mary Worth was different because I made a lot more money on Mary Worth. The pie was cut too many ways with Batman – the syndicate, DC, Bob Kane, and god knows who else was involved. There wasn’t much left for the artist. But it was a good experience. As soon as I left the strip and went back to the comics, DC bought Bob Kane’s contract out and so everybody that worked on Batman was able to sign their work. All those years I was doing the strip, I couldn’t sign my name, but Al Plastino takes over and the first strip he drew, he signed it. [laughs]

How did you end up on the comic strip? Did DC select you or ask you?

John Higgins, the President of the Ledger Syndicate, picked my work. They looked at the comics books and since we weren’t able to sign our names, they called DC and asked, can you get us the guy who did this story to draw the strip? That’s how I got the Batman strip. They liked what I did on the comic book version of Batman and they wanted that same look on the syndicated strip.

Did you get a chance to see the collections of Batman strips that were published a few years ago?

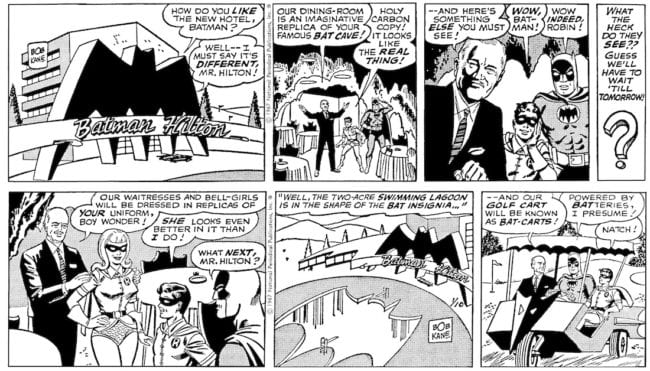

They sent a few copies to me. All the books that I worked on are here. Once in a while I look through them and it brings back a lot of memories. I remember Whit Ellsworth, who was writing the strip, would call me up from California. He’d say, Joe, for this next sequence I want you to design for me the Batman Hilton Hotel. [laughs] Initially when he first told me that I went, what? But I thought, every hotel has a swimming pool, so I designed the pool in the shape of a bat. We got a lot of letters on that. It was a pleasure to work with Whit Ellsworth. He was a really nice guy.

When we started, I drew the strip in the straight adventure style, which was my style. They called me into the office one day and the editor, Mort Weisinger, said, we’d like you to change the strip a little bit. You’re doing it in a straight adventure style and we’d like you to make it a little more campy like the TV show with Adam West. At first I had problems with that. My first job as I mentioned was Captain Codfish with Hillman Periodicals so I could either do straight adventure or animation, but they wanted Batman to be in between those. I finally got it. The letters came in and people seemed to like it. I enjoyed every minute of the strip.

You mentioned talking with Whit Ellsworth. Over the years did you have a lot of interaction with writers?

No, absolutely not. My relationship in comics was with the editor. I worked with Julie Schwartz for 45 years. He was a tough guy to work with but he was fair. We became very good friends right to the end. He was a tough editor. You tell him you’re going to deliver and if you didn’t deliver, you were finished. One time he said he could set his clock on me because I was never late. The one time I knew I was going to be late was when my dad passed away, but I alerted Julie and Julie understood.

So you would work more with Julie Schwartz and Mort Weisinger than the writers.

Oh god, Mort Weisinger. [laughs] He may have been a very talented writer but it was not easy working with Mort Weisinger. I quit the Batman strip twice after he offered it to me. For Mort it was a feather in his cap if he could go to DC and say, I got Joe to do the strip for only X amount of dollars. I would have been making less than I did in the comics – and I had to do carpentry work to make a living at the time. At that time doing a syndicated strip was the pinnacle for an artist. I really wanted to do it, but not on his terms.

The other person people ask me about is Carmine. He’s the one I collaborated with on The Flash and a few other characters. Carmine was an excellent – and undermine excellent – layout man. His style was to draw this way and his concentration was on the layouts. That’s what he excelled at.

One person we haven’t talked about who I know you worked with a lot over the years was Gil Kane.

Kane was a very good artist. Gil Kane was a terrific layout man. He could layout a story and really make it interesting. He could fill up a panel without making it look as if it was fake. In other words, in order to not draw this railroad scene, an artist will put a railroad sign and a big head and just a little suggestion of tracks and part of a train with a little background. That’s called faking. A lot of artists do that, but Gil Kane had a way of doing that where it didn’t look fake. He was that good. He knew his anatomy. His work was exciting. He was a good artist. Gil helped me when my dad passed away. I needed some help on the Batman strip. Gil helped me for one week and then he had his own deadlines and Curt Swan pitched in for me for a few weeks. I’ll never forget that.

There’s a story about you and Bob Kane and how you would draw the art pages for Kane’s TV show.

Bob Kane liked what I did on the Batman strip. I couldn’t put my name on the strip and sign it. I had to put his name on every daily and every Sunday [strip]. He had a TV show on either Saturday morning or Sunday morning, I forget now. I knew about the show but I never watched it. On a large sketchpad I would draw all the superheroes and villains. Every week he would tell me what he wanted me to do. Then on his TV show he was on stage and there was an easel with the pad of my work. I would draw in a very light blue pencil and then on TV he’d take a black magic marker and go over my very light blue lines pencil lines – which you couldn’t see on TV. I did that for a while. A lot of people asked me, how did I like working with Bob? A lot of artists had problems with him, but honest to god, I never had any problems with the man.

Years later, after he passed, the government picked some covers to put on postage stamps. Paul Levitz, the President of DC Comics, called me up and told me the news. None of the artists got any compensation, but Paul said, we’d like to fly you out to San Diego and we’re going to have the unveiling of the stamps there. If your wife would like to come along, we’ll take care of everything. I said a few words on the stage along with Murphy and Carmine. It was very nice. As I was leaving the stage walking down the steps, this woman I never met before shook my hand and said, I’m Bob Kane’s wife. She said, Bob always thought a lot of you and your work. That was very nice.

You mentioned before how you met Dan and Sy Barry in high school, who also went on to become significant artists. And you worked with both of them. When you were working with Dan on Flash Gordon, what were you doing?

A little bit of everything. With Dan, mostly inking but some background work and touchup work. I could name seven or eight artists who worked with Dan on the strip over the years. A syndicated strip is a very taxing. Dan liked to ski and while he was away, Sy Barry and myself would pencil the strip and ink it. I’ll never forget one week we mailed the strip in and somehow it got lost. Dan was fit to be tied. I said Danny, don’t blame Sy. I’m the one who mailed it. We drew the week together but it’s not our fault. Danny understood, but he was still teed off at his brother. They actually found the package ten or fifteen years later. Maybe even twenty years later?

I know that a lot of people assisted Dan over the years on the strip including Frank Frazetta, Bob Fujitana.

A lot of people worked for Dan. Murphy used to work for him, Bob Fuji, Mike Sekowsky. I think Frank Giacoia may have worked for him. I know Neal Adams went to see him one time, but I don’t think Neal did any work on Flash. A lot of people worked with Danny.

How did you end up working with Sy Barry on The Phantom?

I met Sy when I was 16 years old at the School of Industrial Arts. We were good friends. We got together later on after we’d been doing professional work. We both helped his brother Dan with the Flash Gordon strip. In the late sixties after I finished working on the Batman syndicated strip, Sy asked me to help him on The Phantom strip. I worked with him three days a week for seventeen years. And we’re still good friends. [laughs]

So what were you doing those three days a week? How did you two work together?

Whatever he wanted me to work on – inking, background work, wrapping the packages and calling the messenger service. I would go over Sy’s house. I only lived 15-20 minutes away so three days a week I was there working on the strip. When he went on vacation I would take over the strip. Our styles were pretty similar. It’s dangerous when two guys are working on one character because you try to make the drawings as close to the style of the person you’re working with. A lot of artists don’t. They have an ego and think this is what it should look like. When Sy and I worked on Flash Gordon, we tried to do what Danny did. Sometimes it worked out and sometimes it didn’t. Sy and I were pretty close and we still are. I don’t see him as much now, although I did see him last week. Burnt Toast, that’s a comic group that gets together the last Thursday of every month and we meet at this restaurant and well, all hell breaks loose. [laughs] We reminisce and it’s a good time.

When you were working with Sy on The Phantom, did you deal with Lee Falk or the syndicate? Or was it just you and Sy?

Just the two of us. I met Lee Falk once. King Features used to have a Christmas party where everyone who worked on the strips was invited. I went to a few. A lot of artists were there. I met Lee Falk and his wife. Lee was an elderly man and his wife was very young. We shook hands. That was the only time I ever met him. I never worked with him directly. Sy periodically would talk to him on the phone. Lee was very emphatic about things that he wanted. Everything had to be his way. Lee had a lot of muscle. He had two strips, Mandrake the Magician and The Phantom, and these were top strips.

You said before that you did a lot of DC work not for the comic books. What kind of work did you do?

I did a lot of licensing work. My editor was Joe Orlando. I was the artist for Nabisco and I did all of the artwork for them. I did penciling, inking and color separating. At the time now you do a color drawing and give it to a printer and they print it but years ago we had to separate every color. A lot of guys didn’t know how to do that but I did. I learned how to do that. You cut a piece of film with a knife and peel away what you want colored and what you don’t want colored so the other part of the film remains. Each color had to be separated by a film with register marks so when you put one on top of the other they would print evenly. That’s the way we did it years ago.

I did a lot of work for the National Biscuit Company. I did Say No To Drugs. I did coloring books. That’s how I got the Mary Worth strip actually. I did some licensing work for King Features and they kept my samples. Years later when the artist that was doing the Mary Worth strip was terminally ill and then he passed away, they called me. I asked them, how did you get my name? They said, well Joe you did work for us years ago and we kept the samples on file. The one who kept the samples, Karen Moy, wound up writing the strip and collaborating on the strip with me when John Saunders passed away.

Were you offered Mary Worth, or did you have to try out for it?

They didn’t just outright offer it to me. They said, we’d like you to try out for the Mary Worth strip. Jay Kennedy, who was the editor who called me, said a few guys tried out. Years later I found out that twelve artists tried out for Mary Worth. Dick Giordano was one of them. Dick Ayers tried out for the strip. They must have seen something in my work that they liked. They must have felt the same way when they offered me the Batman strip.

When you were working on strips, did you want to know the stories or did not care that much?

When I first got on Mary Worth, John Saunders called me up and said, Joe, you’re not going to like working on Mary Worth. He said, you’re used to superheroes flying off buildings and crashing through windows and Mary Worth is a different type of strip. I figured, no problem, but he was right. If you’re going to compare it to superheroes, it can be boring, but you create interest in the strip through the characters and the storylines and the expressions and good drawing. One compliments the other. Every time I get a script I try to capture what the writer wants. Not what the artist wants – which is easier to draw. I really tried to capture what the writer wants. When John passed away, this amazing gal, Karen Moy, took over. She’s a nice person and she had problems because every time she wrote something she’d call me up and say, Joe, I don’t know if you can draw this and that. I would tell her, I can do that one but the other layout isn’t going to work. She had to educate herself on what an artist can do and cannot do. I told her, any time you have a problem, call me up and I’ll let you know if I can draw it or not. We’re working together on this. It was a very nice relationship. She’s still writing the strip.

[laughs] When I took over Mary Worth the late editor Jay Kennedy from King Features Syndicate said, Joe, I wasn’t too happy with the artist who was drawing it before you. Can you take some of the wrinkles out of her face? I had no idea what Mary Worth’s age was. I knew she wasn’t a teenager, but I figured 50. I took out a few wrinkles here and there and then on the front page of the LA Times – I still have the article – “Did Mary Have a Nip and Tuck?” [laughs] The editor called and said, Joe, you made her too young. I asked, so how old is she? He said she’s supposed to be a good looking 65 year old lady. Now he tells me! John Saunders, the original writer, came to my defense. He called me up because he wasn’t happy with how she looked before. He said, I’ll leave it up to you. Don’t do it gradually. Just change her. I mentioned this to Jay Kennedy and he said, go ahead.

So no one was happy with how she looked before, but you had to please everyone somehow.

I designed her to look similar to Angela Lansbury. She’s a good looking lady. I did Mary Worth’s hairstyle over. I made her statuesque, taller, and just nicer. I still have the original sketch I submitted to the syndicate. They asked, is this how she’s going to look? I said, if you approve it. [laughs] Any character that I designed I submitted them to the syndicate prior to drawing them in the strip. It worked out, but oh man, did I get letters. Some were complimentary but some asked, what happened to Mary Worth? That calmed down after a few months and everybody got used to the new look.

So when John Saunders said you would be bored, he was wrong. You found plenty to learn and different ways to work.

The boredom was just temporary. I had to find ways to make it interesting. I did it by creating characters in the strip. Mary Worth ran a hotel complex and the stories originate from permanent guests and people staying at the hotel. That was interesting. One time I suggested a story to Karen. There’s a murder in the complex and Mary Worth gets blamed. You can see the headlines, Mary Worth jailed for murder! All of Mary’s friends come to her defense and week after week they find clue after clue. One of the main characters, Ian, confronts the murderer and overpowers him. You could really build it up. I mean, I couldn’t, but a writer could. [laughs] I told this to Karen and she said, it’s a great idea but it would never go.

But when you were working with Karen and before that with John, they would they say, we’re going to do a storyline for four weeks, this is the story, it’s going to have this new character, and they would send you that before they would send you scripts.

Exactly like that. We’d speak on the phone for about an hour and then she’d send me a two page outline or something. She would go over what would happen over the next eight to ten weeks. I would never make any changes unless I felt that I couldn’t do something with the art. Any time Karen needed reference for something in Manhattan, I would get the reference. I would tell Karen, the story is fine, how many weeks is it going to run? She would say, I’m not sure yet. That was John Saunders’ problem, too. He had trouble ending a strip and Karen had trouble beginning a strip. Everybody’s different. She would send me that long outline and if there was something I couldn’t do, we’d solve the problem then. When she got the okay from me, she would submit it to the syndicate. Then they would make their comments. Her job was much more difficult than mine. If you get a good story and good artwork, you’ve got a winner. If you get good artwork and a bad storyline, you’re going to lose. I don’t care how good the artwork is. If you get a good storyline and bad artwork, you can still make it. Because the story will carry the bad art. Of all the strips I worked on, I found that to be true. I always preface that by saying, this is my opinion. Because what do I know? But if you have a good story and good art, you got a winner. Sometimes. [laughs]

You drew Mary Worth for 25 years like you said and then you retired when you were 88.

I retired from the strip in 2016 and all I’m doing now is going to a few conventions a year and some panels and meeting the fans. I do some commission work. I don’t take deposits. If I ever took a deposit and didn’t finish the job I don’t think I’d be able to sleep. The line moves slowly but it does move. I paint. I love to oil paint. At shows I ask the fans prior to signing their books, would you mind if I look through the book? I flip through and it’s very depressing because most of [the people] are all gone. I like going to conventions and meeting the fans but it’s sad to look through the books. I’ll remember collaborating with Murphy on this job or I’ll remember Joe Kubert came in the office one day I was working on this. You get these flashes when you look through the books.

You mentioned before that you had finished a job for Archie recently.

You mentioned before that you had finished a job for Archie recently.

Archie Comics asked me to draw a cover for them with Batman, Robin and Archie on the cover. They just picked up the phone. They wanted me to pencil and ink it. I asked if they wanted color and they said, we have people to do that. They did the lettering also. As a matter of fact the editor came to my house and we were discussing what he wanted. He bought me some reference for Archie. I worked on an Archie story many years ago but you want to get the character right. When he left I knew what they wanted. I enjoyed doing it.

You retired two years ago like you said, so you’re drawing and painting still, but no more deadlines.

No more deadlines. 72 years in the business and now there’s no more deadlines. I get up in the morning and I have breakfast with my wife, drink my coffee. I’m relaxed and I love it. [laughs] Of course I’m 90 now. All my brothers retired thirty years ago. My brother Johnny was a city fireman. My brother Frank worked for the city. Billy was a police officer. We freelancers don’t have that luxury. Artists don’t get pensions. Vacation? I didn’t know what a vacation was. Now I just take it easy and when I’m alone with my thoughts I think, how the hell did I do it? It’s crazy. [laughs] You have to have a good woman, and I did. I’m 64 years with the same woman. It just happens. You don’t plan it. I could write a book.

Sixty something years of marriage during seventy something years as a freelance artist is something.

72 years in the business. I unbelievable. It’s like a dream. Where the hell did it go? [laughs] But I’m still doing projects like the Archie cover and taking commissions. I still feel that I have not done my best work yet. Dan Barry once told me, “Joe, you’re like a fine wine, you get better with age.”