Few modern cartoonists have managed to appeal to as diverse a comics readership as Paul Pope. He initially built his name in the indie small-press scene, self-publishing books like The Ballad of Doctor Richardson and the sci-fi oriented THB. Then he managed to carry that goodwill to Vertigo projects like Heavy Liquid and 100% and eventually to superhero projects like Batman Year 100 and Wednesday Comics. In the process has Pope has been able to garner love and respect from two factions of American comics culture that rarely enjoy each other's company, no small feat.

Few modern cartoonists have managed to appeal to as diverse a comics readership as Paul Pope. He initially built his name in the indie small-press scene, self-publishing books like The Ballad of Doctor Richardson and the sci-fi oriented THB. Then he managed to carry that goodwill to Vertigo projects like Heavy Liquid and 100% and eventually to superhero projects like Batman Year 100 and Wednesday Comics. In the process has Pope has been able to garner love and respect from two factions of American comics culture that rarely enjoy each other's company, no small feat.

Now, he's reaching out to a (for him) new audience: Kids, via his much-delayed but highly anticipated graphic novel Battling Boy. The book, a slam-bang action adventure about the tween child of demigods sent to save a city plagued by rampaging monsters, made its way to a number of top-10 and "best comics of the year" lists for 2013. Writing for this site, Charles Hatfield described the book as "dynamic, brash, stuffed with surprises, yet also knowingly crafted, tightly braided, even subtle," and claimed that "it is Pope’s best balancing act yet between the joys of rampant mark-making and the responsibilities of story." Certainly he was not alone in that assessment.

I spoke with Pope over the phone a week or so after he was wrapping up a major book tour with a stop at the New York Comic-Con. We talked about the book, its origins, the trick of attempting to appeal to a certain audience, and his plans for sequels. Even though he had spent considerable time on the road he was eager to talk about his work and I am grateful for his time.

CHRIS MAUTNER: How did NYCC go?

CHRIS MAUTNER: How did NYCC go?

PAUL POPE: It was good. It was very interesting. They’ve been keeping me busy for sure. [First Second] set up the most elaborate tour I’ve done for a book. What’s exciting though. We did a multi-city tour for schools and for school libraries, meeting 600 to 700 kids ranging from 10 or 12 years old up to high school kids. And then there was NYCC, which included what we think of as comic book fans. [First Second] also had me doing panels with young adult science-fiction/fantasy prose writers. Those were super-packed panels and [the audience] was mostly teenage kids, primarily girls and then some boys, people that read Twilight and Harry Potter and stuff like that.

Were they a welcoming audience?

They were great. They were super-enthusiastic. They’re not at all cynical or jaded. I stopped thinking of them as kids. They’re just little people. A lot of them knew a lot about mythology too, which is quite interesting.

I know you’ve been talking about this a lot, but I wanted to get a sense of the chronology of Battling Boy and how it came to be. Initially this came about because you wanted to do an all-ages superhero book, right?

Yes, identifying what I perceived to be a missing piece of what could be a much larger comic book readership.

Because this originally came out of the idea of you pitching a Kamandi story for DC, right?

Kind of. It was actually more in terms of what might be available at Marvel or DC, what might fit in with what would now be considered to be young adult or all-ages readership. In my mind Kamandi was the closest to … a character I could work with. I was trying to find something that would fit within that spectrum, in the same way that Jeff Smith worked on the Shazam book.

And it evolved from that general idea into Battling Boy?

Oh yeah, definitely. The only advantage to how long it’s taken to get this book out in the light of day is how much story archeology there’s been. I started with the basic notion that at the time most of the material I’ve done up to 2005 or 2006 gad been pretty much adult-oriented – everything from softcore porn through adult themed, R-rated stuff. I have nephews who knew I made comic books and they were interested in that, but I realized I couldn’t give them anything I had done. So I started thinking about doing work for younger readers.

At the time, for my own pleasure, I was reading silver age and golden age comics, early Heavy Metals and looking at [Hayao] Miyazaki films and was thinking about how you really can do some kick-ass stuff that does appeal to kids – or is at least suitable for kids – but doesn’t pull any punches. That was the gestation.

I remember hearing about this book back in 2006 or 2007. What were some of the reasons the book took so long and did that length of time help the gestation of the book or hurt it for you?

It didn’t hurt it. I think in some ways it allowed First Second as a company to have a couple of successes. If we did drop Battling Boy in 2005 as opposed to 2013, it would have been a different rollout for the book. I think they’ve had enough of a track record on their own that when they get something like this property they can work with it on its own terms.

In self-publishing it can get very frustrating to work in an echo chamber and realize that this book might appeal to a wide age range or audience, but I don’t have the connections in marketing, I don’t have the connections in foreign licensing, etc. So all those things come together [in working with First Second]. In my case I had a lot of time to think about the story, do the research, bounce ideas off of people – [I had] some good people looking over my shoulder on this.

The market has changed dramatically from when you first started this story.

True.

Do you think it's more accepting of something like Battling Boy now?

We went to this American Library Association event in Chicago a few months ago and I [had] what seemed to me to be a pretty significant moment. [I’m] on this junket where you have dinner with librarians from public libraries and schoolteachers, and one of them told me she read Battling Boy – we were sort of in this informal setting – she said, “You know this is really cool. A lot of us like graphic novels but we don’t know what else to shelve besides Bone.” It’s Bone, Watchmen, probably at this stage Persepolis, and maybe Blankets. Then the Donald Ducks and stuff like that. She’s like, “This is one we can shelve next to Bone.” Somehow it fits in the young adult category. That was eye opening to me.

Now my understanding is that during this period you were also working on the movie version of Battling Boy and that’s one of the reasons the book took so long.

True. But not only that, [it was] also [the movie adaptation of Michael Chabon’s novel] Kavalier and Clay. I got dropped into making The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay within two weeks of finishing Batman Year 100. And that turned into about a year of work. Initially it was two weeks of work – they needed more specific drawings. I just kept getting more and more entangled in the process, to the point where I was working pretty closely with the core team, with the actors, with all the people in production. It was great in a way; it was sort of like boot camp for film, very different from comics. But it was sort of a creative wilderness for a couple of years.

Did either of those movie experiences change your approach to the book at all? Did it help in the gestation?

We had this slightly hairy situation where we had a graphic novel that was being created alongside a film. So is it a graphic novel adaptation of a film or a film adaptation of a graphic novel? Who’s the author? All these types of [questions were being raised], and that was worrisome. So we established early on that this is my story. To guarantee that I wrote a fairly long prose novella, sort of "What is Battling Boy" – every scene, key sequencing, specific dialogue, here’s the character designs and here’s the rules for the universe, etc. Then I went and worked uncredited on the screenplay in order to regain control over the story rights. That was an education though, because I worked on nine drafts of the film scripts and what we began to see was that rather than adhere to this Robert McKee three-act structure – what’s his book, On Storytelling? On Writing? [Story: Substance, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting]

Something like that

That really is the gold standard for scripting in Hollywood. I find [it] very formulaic and not very interesting. So in a way, I was able to work with the core team [on] this core story of Battling Boy, but in the graphic novel I don’t have to be restrained by rules where if you introduce a character he must come back in the third act. Stuff like: If a gun’s in the room it has to be used at some point. All those clichés, I don’t have to worry about that so much.

With the [Battling Boy] film, where it is now, it’s kind of delicate. The film hasn’t been made. I think it will, but that’s the long road and there are a lot of people that have to make decisions that I have no control over. At the same time, working closely with the core writing team, I can see how some things translate well to film and some work better as comics.

One of the great benefits is I learned how to condense dialogue and in some cases scenes. Three pages of comics ideally would be one scene in a film, which might turn a twenty-page sequence into a two-page sequence for comics. You don’t have to rely on that but sometimes it’s very useful, especially when there’s a long exposition – how do we get to the meat, the action?

It’s been interesting. I have no experience whatsoever in film school or film writing or any of that stuff, so it’s totally like being thrown into the deep end of the pool.

You talked about this being a book for all ages but not wanting to pull any punches. I was curious how aware were you of your potential audience? Did you ever find yourself censoring yourself?

There are three thoughts about that. First, I would say that my editor, Mark Siegel, has been instrumental in this entire project from day one. The film is its own thing. In terms of making the graphic novel, he’s been pretty much the key person I talk to and work with. He said something early on which was pretty liberating. Everyone was wondering, “Can this guy that comes from adult, independent comics do a book for kids?” I worried about that myself, even though that was my intention. Siegel said, “Why don’t you just make the book, don’t worry about it and we’ll figure out who it’s for after you make it.” That was cool, because it allowed me to go off and do what I normally do. I haven’t approached finishing Battling Boy any differently than I have on anything else. It’s just that I know I wanted it to be a kids’ superhero [comic] with kid logic and that I want young people to read it.

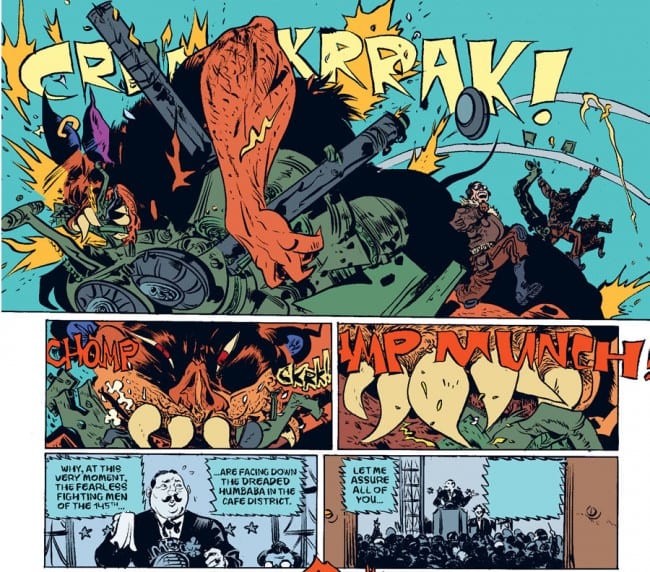

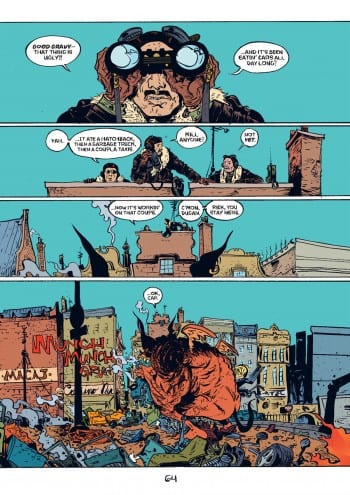

So the first time I sat down and had a situation with this giant kaiju monster eating cars and tearing apart tanks, like that classic Godzilla scene where the army is helpless against this thing. There’s a scene where the monster is tearing apart the tank and there’s people inside the tank. And my first instinct was to draw the bodies being ripped apart just like the tank is being ripped apart. But if I go down this road then this is R-rated and is going to appeal to the people that already pick my stuff up and like it. But if I choose not to kill them – it doesn’t have to be bowdlerizing it, where there’s no death, no violence, you just don’t show it in-panel. And that way you don’t alienate the youngest readers that are going to pick this up and engage and get into it for other reasons. So there was that.

In terms of readership, I’m kind of shocked to be meeting young people who are reading this. I sort of had this ideal reader in my mind. I didn’t have a Wall Street demographic thing where you think, “OK, here’s how you make a book for 12-year-olds. It’s more like I’m seeing how to appeal to them. I thought more: “What did I like in those days, what did I think was cool?” So I’m throwing in all this stuff from all over, from anime to Heavy Metal to Jack Kirby. Anything I thought was cool.

It’s not like the villains or the monsters [in the story] aren’t a genuine threat. There’s a tension in that the monsters are nasty. There are some rather disturbing allusions as to what’s happening to these kidnapped kids. I thought it set the stakes rather well.

You remember when we were kids there was some heavy shit in fantasy and fairy tales. It’s pretty classic: There are monsters coming out of the ground, kidnapping children, they come out at night; these are rules that everybody knows. They are collecting children for some purpose that has not been revealed. Kids can handle that. I think it’s the way it’s portrayed. Stories about child abduction, those are really dark, sinister things and they’re real. But the story isn’t about a specific real kid getting abducted, which would be terrifying to an adult let alone a child. Kids know they’re not safe in this world. They’re defenseless in many cases. So the thing I hit on was a child protector who is also a child.

There’s a lot of interesting stuff you can do with that idea, without exposing them to too much violence. There is more in the second book about what these monsters are actually doing with these kids – they’re not raping them or anything. But kids understand that this does happen. I trusted that when I went into this.

Where did you come up with the idea of having the t-shirts serve as totems?

Honestly, I’ve been asked this and I’ve thought about it and I don’t know. There are the twelve t-shirts and that ties into the twelve labors of Hercules and the Zodiac, twelve months of the year, a numerological thing. I did have my nephews in mind: What would they think is cool? I always buy them T-shirts, ever since they were little kids and they always thought T-shirts with cool graphics had a certain kind of currency at school. “If the nephews will think it’s cool then I think it will work.” That’s a bland answer but it’s the best I can come up with.

Battling Boy is very steeped in Campbellian-style “Hero’s Journey” mythos. How much research or studying of those archetypes did you do?

Oh, a lot, a lot. There were three major sources. I’m also a big Carl Jung student. There’s a book called Memories, Dream's, Reflections. There’s also a book called Man and his Symbols. And Campbell. Everyone knows The Hero With a Thousand Faces and his book with Bill Moyers, The Power of Myth. He has another one called Creative Mythology, which is a much longer, more academic book. It’s very interesting and gets into the specific, slightly off-the-beaten-path strain of story. Those were very useful.

Robert Graves has a translated [edition] of Gilgamesh. Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf, and of course Dune and the Tolkien books. There was an essay [Unreal Estates] between Kingsley Amis , C.S. Lewis and ... I’m blanking now on the third person [Brian Aldiss]. It was another English writer from the Inkling society of mid-century science-fiction/fantasy writers. They talked about what they called unreal states, how do you write fantastic fiction? And Lewis made a really great point where he said when you’re writing for children, you don’t write to them, you write a simple story that makes sense, the broadest sense.

I liked that. I felt like that was a really liberating idea because it meant that, you know what, fuck it, this is a comic book. It does all the stuff superheroes do – he has weaknesses and powers – it’s just that they’re not super villains robbing banks, they’re monsters kidnapping children. I tried to find a way to use this classic fantasy/fairy tale underpinning to tell a story that superficially works as a superhero comic book in the classic sense. So that was sort of what I was going for.

MDid you feel like you had to plot the book out ahead of time to meet that kind of structure? Was there a lot of dotting of i's and crossing of t's?

Oh yeah. Absolutely, because if nothing else, in order to get the book sold, they’re not going to give you a contract if you don’t have a story written out. That sounds elementary but I learned that. The first time I had to get really serious about delivering a solid script was after I turned in Heavy Liquid, which had a pretty tight script but there were still some holes in it. Working with Karen Berger, she was like, “Well we like this script but you need to convince me. This is like a romance comic, and you want to do it black and white, where nothing happens, there’s no gratuitous sex or violence.” [I thought,] "OK, I need to persuade you that this is the kind of story I believe this to be." I did provide a script for Batman 100. They’re not going to give you Batman if you don’t know what you’re doing with it. So I applied the same rules [to] Battling Boy.

At this point all I’m doing is drawing the story as it’s written. There’s room for some improvisation for sure. I tried to leave some holes in terms of action and the direction of things but in terms of the nuts and bolts from scene one to scene 300, the story is pretty tight.

Listening to you talk I get the feeling that you’ve had a very valuable relationships with your editors.

Yeah, by far.

Is that something you look for now? Can you talk a little bit about what you’ve gained? There are plenty of cartoonists that just want to be left alone to do their own thing.

I did that also. The first seven years of my career was working as a self-publisher. The only input I got was letters from readers. There was no editor on THB. There was no editor on the Ballad of Doctor Richardson or any of that stuff. The first time I had an editor was when I worked on the One-Trick Rip-Off with Bob Schreck and then subsequently Batman Year 100. I was getting a lot of complaints from people before that, where they’d say, “Oh the drawings are good, but the stories are kind of light” or “They don’t go anywhere.” That was frustrating because I wasn’t trained as a novelist or a story writer. I was trained first as an artist working in different disciplines whether it’s art history or studio art. And then as a printer, where I was doing everything from working in a commercial printing house doing web-set printing, printing magazines and menus and things like that. So working with editors was the first time I had to get muscular, in terms of writing.

But you feel like those relationships have helped you as a writer and storyteller?

Yeah. I think I would take it a step beyond that and say it’s more primal to have [that] rapport. Your editor is like your Virgil. You need to be able to have a guide or at least a companion when you walk through Hell. With Mark Siegel at First Second, we’re taking it to a different level, where we just got off a multi-city [tour]. We’ve been on the road together, we go to bed at the same time, we get up at the same time, we’ve eaten every meal together, we’re on trains and planes and automobiles together – we’re pretty much together constantly on this junket. Now that Book One’s done we took a train back from DC a couple days ago and we spent the entire time thumbnailing out [what] I need to get done when I get back from Toronto. In a sense, it’s sort of like a creative marriage. He’s a coach, he’s a cheerleader, he’s a taskmaster, he’s a friend and a sounding board. I think ideally that’s the most harmonious relationship between the editor and the artist.

You talked about wanting to create the kind of all-ages superhero story you liked as a kid. Do you see that as a hole in the industry currently? There are all-ages books out there but is there anything like Battling Boy out right now? And what what does it say about the mainstream if these stories aren't so prevalent aren’t any longer?

We can talk about the role that the editor plays, an editorial dictate that comes down and creative teams that get hired do what the editors tell them to do, I think at the end of the day, the ones who can really demonstrate the story should be the ones that can actually make them.

Take a look at the barometer of what is culture or what’s going on. There seems to be a bit of a vortex here. When I was [coming up with] Battling Boy there wasn’t anything like that, with elements of manga, elements of silver age comics, elements of Heavy Metal magazine. I thought, "I can really pull this off, I just need to find the right place to do it." That was the hope. The trick was the right publishing team and the right marketing muscle behind it to pull it off. Having come from self-publishing, if it came down to it, I could have self-published Battling Boy, The great frustration I had is I don’t know how to get into school libraries. I don’t know how to get into foreign markets with trustworthy publishing teams. I knew I needed a partner.

I wanted to ask you about your influences for Battling Boy. I can see Kirby, especially Thor and Fourth World. And definitely Mobieus and Heavy Metal, especially with the scenery. I wanted to specifically ask you about manga though, because I know manga has been a huge influence for you. Were there specific works or manga-ka you drew upon? I was thinking of Tayio Matsumoto at times.

Not at all an influence on me, I have to admit. Not to derail you, but he’s not at all an influence on me. I respect Matsumoto, don’t get me wrong, I [met him] at TCAF in May. That was awesome. It’s more like … do you know Yuko Shumizu the illustrator?

Yes.

We pretty much grew up looking at the same stuff, everything from Guido Crepax to Tezuka. It’s more that Matsumoto and I share influences as opposed to …

…Influencing each other.

I don’t really know him and I have to admit I don’t look at his work much. I think he’s good, I can identify his style, but I kind of circle the wagons in terms of what I’m looking at. I’m only looking at Kirby, Miyazaki and Moebius.

Were you specifically returning to these artists or was it more a subconscious thing? Were you pulling books of the shelves?

There was something I got from [Alex] Toth that I thought was very useful. He didn’t use photo-reference. What he would do, if he had to draw John Wayne or a specific car, he would study it, put the book down, and then go and do it on his own. And I tried my own way to use that Toth-ian approach, but in terms of tone. So I would spend some time looking at Moebius. There’s a shot in Battling Boy with a giant city. I knew I had to quickly and elegantly show the scale of the city and I knew it had to look kind of Mediterranean, old and ossified. And so I was looking at a lot of Moebius, specifically Inside Moebius, his later stuff, and then put it down and created something out of my brain. Moebius uses a lot of these Leone-esque horizon line shots where you’re seeing something over the shoulder, from ground level. That kind of telegraphs “epic,” widescreen stuff. That was what I was going for. So I’d look at Moebius, put it down and then think about it and make my own thing.

It strikes me as a tricky thing, that narrow line between drawing upon and utilizing your influences but making sure it’s your own voice and not re-appropriating something.

Joseph Campbell made a very interesting point, that if there was a battle that we think of as the Trojan War – you know, the story of The Iliad – before it was written down it was a battle that would have been 6 to 8,000 years earlier. This was a battle that would have happened thousands of years before it was written down. He makes a point with the oral tradition, which is where storytelling must come from: You memorize and then retell the story. The point is that in some way you embellish it. That’s how you honor the stories; you add something to it. So that you tell the story, whether Agamemnon or Paris or Achilles, you add something to it so it’s different and [has] changed. There’s a bit of a germ you put in the story with this little inflection.

That gave me confidence, and that’s why I stuck Humbaba in, who is taken from Gilgamesh, the Sumerian myth. [According to] my research it’s the oldest written monster, a fantastic character in literature. Like Grendel, he’s an interesting character where he has different inflections depending upon how he’s told. I knew he was a special monster and I knew I wanted to use something that indicated the story is drawing upon an ancient sources of stories. I tried to use the same approach with Kirby, where I’m visually telling the Fourth World story but adding enough to it that it becomes a different story. I’m indicating this story takes place in this sort of world that we know. Whether it’s Kirby’s work at Marvel or DC, it has that stamp on it, but it’s not a Kirby story.

The cool thing is like I’m meeting all these 10- and 12-year-olds and they have no idea who Jack Kirby or George Grosz is. They’re just getting it as pure story. And ... maybe they’ve read Adventure Time or Archie, but they’ve never seen a story like this.

I talked to Jeff Smith at SPX and he was saying how for so long it was thought that kids won’t read comics anymore and now kids are reading comics and don’t have a problem reading them. There’s no stigma anymore. Educators have made it OK.

It’s not awkward. When [Mark Siegel] introduces the talk – depending on the age group I do a 25-minute presentation, like, “This is how you make a comic book page, this is about the story, here’s how you make a superhero, etc.” When he introduces it, the first question he asks the kids is, “How many people here read graphic novels? Who here likes comic books and graphic novels?” I’ve got to tell you, no matter where we are, whether it’s rural Indiana or urban D.C., almost 100 percent of the kids raise their hands. They’re super-enthusiastic. It’s eye opening. We go to shows like SPX and there are people that do small comics and silkscreen covers for a fanzine. That stuff is not really accessible to these 10-year-olds, who get their comics or graphic novels from the school library. So it is extremely eye-opening.

There’s a distrust of adults and the government in Battling Boy, especially with the Mayor. That makes sense in that Battling Boy is on his own but I was wondering if you were making a larger point in the way the mayor and other forces were trying to manipulate him for their own political ends.

I don’t have a personal bone to pick in Battling Boy. It has more to do with manipulation of children. The mayor’s job is to keep civic order and trust. His power is speech and the authority of the police. They’re sort of buckling under the weight of this invasion. The people don’t feel safe, that’s why they’re looking for a hero. In the story, I don’t see the mayor as a bad guy. He’s doing the best he can. If you look at the three main power figures – we’ll leave the captain out for a second – we have the mayor, we have Aurora and we have Battling Boy. Battling Boy wants to figure out where the monsters are coming from, Aurora wants to destroy the monsters, and the mayor wants to keep civic confidence and that makes for an interesting tripod of power and intention. That’s something I’m trying to play with in the story.

There are these jokes about marketers focus testing his name and funny things like that. That kind of stuff happens though if you look at child celebrities, whether it’s Miley Cyrus or Justin Bieber. Whoever it might be, these kids get a little twisted because there are people handling them – and you know they are getting some kind of financial gain, a status from using a child that’s not fully emotionally developed. There’s an element [of that] in [Battling Boy’s] interaction with the local authorities. It’s funny you mention that because no one’s actually brought that up yet, but that’s something I intended.

You mentioned Aurora. I was taken with that character. She almost seems like the co-protagonist of the story.

She is.

And you mentioned Miyazaki earlier, which made me think of Aurora.

Oh yeah, definitely. And that’s why we held it back. My thought was now she’s getting her own series – which is amazing – and she’s got her own story arc and her tradition is more science and action-based in the sense of Indiana Jones or (being into comic books) Batman. Her father doesn’t have any superpowers. He’s just super smart and rich. He’s well connected and he can build gadgets. She comes from that tradition. Battling Boy, because he’s the son of a demigod, he doesn’t have to worry about those sorts of things. But it also makes him more aloof, so he’s not really invested in [the town]. In young adult fantasy fiction, [there’s] the “The Chosen One” archetype. He’s not really a chosen one. He doesn’t want to be that. He just wants to please his father and his mother. She wants to get revenge on the killers of her father and mother. It makes them an interesting pairing because they’re both trying to do the same thing, keep the city safer. In order to do that they have to work with the mayor, and the mayor wants to keep the peace and he’ll do whatever it takes to make sure that works. I think that’s a pretty realistic framework. I think you see this all the time in society – whether it’s the government shutdown or if Miley Cyrus suddenly fails and how do they [stage a comeback], all that type of stuff. There’s a little bit of celebrity commentary in there, cultural commentary.

Now there’s one more volume of Battling Boy coming out, right?

Yes.

What’s the plan for that? When is that coming out?

What’s the plan for that? When is that coming out?

I don’t know. I don’t want to go on the record and say when the date is. It will kick me in the ass, but I know it won’t take six years for me to get the book done. But because we’re expanding the universe and building on the stories – it’s no secret that the hero, Haggard West, has to die before the story starts. I was pretty despondent the day I drew his death scene, I was like, "Man, this sucks." He’s such a great character and as I was drawing him I made up an entire backstory for him and his family. He’s an archeologist investigating how old this monster problem is, because there were other cities before there was Arcopolis, the setting for this Battling Boy story. So when First Second was like, "Do you want to expand upon this, do you think you have other stories to tell?" Well yeah, I think there’s a lot of stuff we can do with Haggard. He’s a hero on his own.

I’ve been working for a year on the script with JT Petty. I know I wanted a European artist, specifically a Spanish artist, to draw the stories, the background for Aurora. So the way it works out is [first] Battling Boy one, then it will be Aurora book one – that’s already been announced for sometime before San Diego next year – Battling Boy two, which I’m hoping is going to be next fall – a year later in other words – and then Aurora book two. They tell two separate stories but when you read them together, it’s one big story. Aurora is ... I don’t want to say prequel but her series ends where Battling Boy begins and then her story arc ends at the end of Battling Boy two, so the whole thing tells her story really. Battling Boy has his own story, but his initial coming-of-age story ends with Battling Boy two. And hers continues through the two series.

What made you decide to work with another artist on the Aurora books?

It’s going to take 20 years if I did all of this by myself. I think it’s a good sign of leadership to be able to delegate and my editor Mark brought in Petty and said, "I think this guy can work with you, he really has a handle on horror fiction. He knows how to write graphic novels. How do you see the art going?" And I said, "Well, I want it to be similar to mine and yet unique." And they were cool with bringing in a European because I come from more of a Heavy Metal background. I wanted it to feel European. And so I suggested David Rubin and luckily they said yes. He comes from animation so he’s fast. And that’s good for morale because he and I are now working on two series together in the same universe at the same time, and that’s kind of like Wimbledon, where we’re volleying back and forth.

Do you see this as being a continuing saga? Do you see yourself doing other stories set in this universe?

Oh yeah. We’re introducing lots of characters. We have three realms: The monster realm, the god realm and the human realm. We tried to give each realm it’s own purpose and all the characters have their own stories and potentials. I’m thinking just to try to put a stamp on the Campbellian/superhero universe that’s what I’m trying to do with this, and it seems like people are picking up on it, so it’s good.

It reminds me of the Jack Kirby’s Fourth World where he had this core idea others could branch off on.

If you’ve read those old comics, I think it was The New Gods #5, Orion battles the Terrible Turpin. When you sit down and look at Kirby battle scenes, it’s almost like scenes of glaciers exploding, because he only has about four panels per page, these massive bone-crushing battles, but he only has four pages to do it. Having come from manga ... in my mind I’m thinking, "God, if Kirby could have had the freedom of manga, all the energy and verve and electricity we think of with Kirby, if he could have had more space, how amazing those fight scenes would be." His mental choreography was so strong, brutal and so convincing, that was an exciting impetus to do something like Battling Boy, where there’s room for a 45-page fight scene.

The police chief reminds me a bit of Terrible Turpin.

The police chief reminds me a bit of Terrible Turpin.

Yeah, he’s a classic Frank Capra, Robert Mitchum type. Those guys are deliberate 1940s flying foxes. Someone mentioned the Blackhawks, you know, the DC comic? I hadn’t thought about it, but that’s exactly what they are. The Howling Commandos. They fit that mold. They’re like the crack commando team that back up the superhero. And of course, one guy on the team is named Dugan, deliberately, to say I know where these guys are coming from. They’re like the Howling Commandos.

I’ve always thought that you straddle a couple worlds. You came out of the indie scene, you self-published and came out of the small press, but you’ve worked with DC and did a Batman comic. You’ve got fans who belong in the more traditional mainstream world. You seem to have this career that straddles worlds that traditionally don’t mix. I always thought that was interesting. You’ve amassed a reader base that doesn’t seem beholden to a particular genre.

That’s always been my intention. When I got into the game in 1990-91, it felt like there were only a couple of options open if you were going to get into comics – this was before we achieved anything from a critical literary or financial success for whatever that’s worth. I always chafed against that, because I come from an art history or art school background and ... guys like the surrealists were inventors. They looked at the conditions around them and came up with their own solutions, their own way of responding in an interesting way. Whether it’s punk rock or cubism, there’s always a way to fracture something and put it back together. I always try to approach things from that [aspect].

Any chance of any more THB comics down the line?

Yeah, there is. That’s the white whale of indie comics, right? In fact, I’ve got a number of book deals signed with First Second because when Battling Boy is done – this is actually pretty amazing: You think about those 10-year-olds reading Battling Boy, with the psychology and lifestyle and mindset of an 11-year-old. By the time Battling Boy and Aurora are done? The kids are going to be 14 to 15, and that’s the perfect age to read something like THB. It’s also the perfect time to read Dune or any other young adult science fiction/fantasy stuff.

So the intention is to finish Battling Boy and then for me regardless of whatever happens to the Battling Boy universe and my role in it, for me to move on to THB. It’s a different type of story. It has more to do with politics and economics and manifest destiny and a metaphor for western expansion across the Americas, all those kind of things. So I believe it’s now a five-book deal for THB. It’s being finally collected in color, typical format. Total THB is the name and then we’re also doing an "Absolute" artist edition in black and white, which is more for [those] who want to see the line art. That’s going to be larger,like my old THB. That was Mark Siegel's idea. It wasn’t my idea. It was something he wanted.