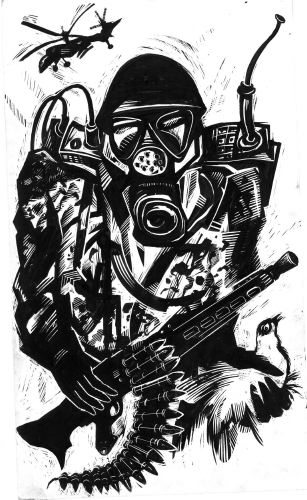

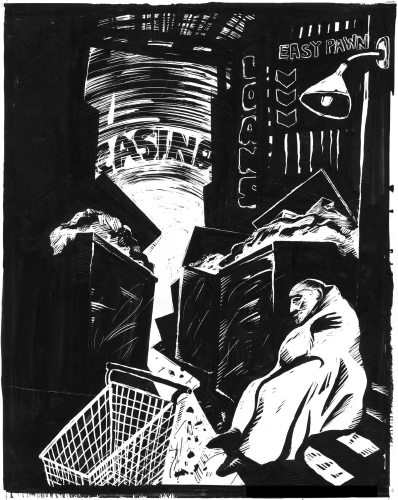

Carel Moiseiwitsch drew dangerous comics. Prominently featuring murderous cops, third-world refugees, and war crimes hopscotching their way to our front door, her works were dangerous because they gave us the raw truth, seemingly drawn in dense black sauce. Moiseiwitch had a period in the mid-to-late 1980s where her comics about punch-drunk authority figures taking turns making a mess of our lives were printed in all the important publications of the time: Rip Off Comix, Wimmen’s Comix, Weirdo, Real Stuff, and Twisted Sisters. As Moiseiwitsch drifted away from comics, like many of the singularly eccentric greats of that era did, she became more involved in fine art and world-wide activism. I spent more than an hour on the phone with the 76-year-old cartoonist and painter recently; we discussed a life full of art and advocacy.

RJ CASEY: How are you today?

CAREL MOISEIWITSCH: I’m good. The weather has been very unpredictable. Sometimes very hot or very cold. Very windy. Things have been polarizing and surprising since moving to the country, that’s for sure.

When did you move out to the country?

A few years ago, to get out of the city. We moved to Fraser Canyon. It’s been interesting.

You’re originally from England?

London, yes.

What was your first exposure to art?

My first exposure to art? Oh, I don’t know.

Do you remember a certain drawing or painting or something that really struck you when you were a child?

Where I grew up there wasn’t very much art. It was drab and desolate most of the time.

How so?

It was like a boarding school. I remember liking some children’s books with dark stories and dark illustrations. I was already attracted to that at a young age.

This was around World War II, right? Do you remember it at all?

I was born during the Blitz, but I don’t remember war. I was too young. But I remember the aftermath.

What do you remember?

I remember playing around the rubble. We used to look at bombsites and find wood and stuff. There were lots of bomb shelters and things like that during the ’50s and ’60s.

So that was a common site for you when you were a child? Places that were bombed out and bomb shelters?

Yes, yes. Everyone had that experience, especially if you lived in or around London. My grandmother lived in a place like that in London. After that, my parents just sort of split up and left me at school. I never saw them again. So the war had a direct impact…

Did you say you never saw them again?

I saw my father very, very scarcely and I didn’t see my mother again until I was eighteen.

Whoa ... what were they doing during that time? Do you know anything about their lives?

Getting married again, to other people. Having more children, as people do. Yeah, they weren’t a part of my life.

Then you eventually found your way to the Saint Martin’s School of Art.

I did, yeah. In London.

Were you mainly focused on fine art there? Or illustration?

Fine art. I took painting. They do printmaking and fashion design now. Probably animation too. But at the time, they didn’t even have illustration. I did painting. Or my interpretation of painting. [Laughs]

Was it oil painting?

We did all kinds of painting. Gouache. Oil. Whatever you wanted.

OK. Going off on a tangent for a second because we’re talking about Saint Martin’s — I talked with Peter Bagge yesterday …

Oh Pete! How is he?

He’s good. We live in the same city now, so we see each other occasionally. After I told him that I would be talking with you, he said you had good Rolling Stones stories. He said to mention the Rolling Stones because you knew them when they were teenagers at Saint Martin’s?

Yeah, they used to come around and play at the art events at Saint Martin’s and the school dances and things like that. David Haughton used to come around and he tried to organize a painter’s guild. My friend, who I lived with and would see these guys at poetry readings, he was an electrician and wired up Jimi Hendrix for a local concert. I mean, how do you wire up Jimi Hendrix? I think he had to kind of make it up on the fly. There was all that stuff going on around me. All that early rock ’n’ roll.

After you graduated Saint Martin’s, was the next stop Vancouver?

After I left school, you know, I got pregnant and did all those things that you do. All of my friends became very boring and I thought that my life at that point was just mapped out ahead of me.

What do you mean mapped out? What did you picture?

It just seemed like there was going to be no deviation. I could see what was going to happen to me, and it seemed terrible. I just knew how predictable my life was going to be. A middle-class nobody in London. Just daft.

What did you think was going to happen?

That I would buy a house and decorate it nicely. Have more children. It just seemed horrible. I didn’t want that. So, the West Coast of America seemed like the place to go.

All the pop songs were about that, right? The Mamas & the Papas, The Beach Boys, even Dylan. You got the impression that it would be good to go to the West Coast of America. But anywhere in America would have been good.

Did you make it to California then?

I went to Canada first because it was easy. I had planned to make it down the coast, but I didn’t. Vancouver was the farthest I got.

What was Vancouver like when you got there?

was a small, provincial town basically. I was coming from London, so … it was very slow. Shops still closed on Sundays. It was in the early ’70s. There was a real sense, though, that if you were a single mom of three, you could get by rather comfortably just with one income. There were some art grants and you could get this, that, and the other. Something relaxed about it.

You went from London to Vancouver with three children with you?

I went to a few other places briefly, but didn’t like them. I tried to go back to London too, but didn’t like that either. So, yes, Vancouver with my kids.

Was that difficult?

[Laughs] I think it probably was! But I didn’t know any better. It beat being stuck in a middle-class nothing life in London.

When you got to Vancouver, were you still painting or creating art in some capacity?

I was struggling and I used to make excuses — the kids were always in the way or something like that. But one day I remember setting up and completing a painting that I really liked. It was a real breakthrough for me. After that, I realized that the kids didn’t really bother me if I was actually concentrating. They left me alone. They were smart.

[Away from phone] Get down. Hey! Get down. Thank you.

I’ve got a puppy that I’m trying to train not to chew on the end of the couch.

[Laughs] You’ve got a puppy?

Yeah. It’s almost not a puppy anymore — one and a half. But still has some residual chewing issues, so we’re in training.

Are you an animal person? Have you always had pets?

No, I haven’t always had pets. I had children. That’s enough animals. [Laughter] But they had pets, yeah.

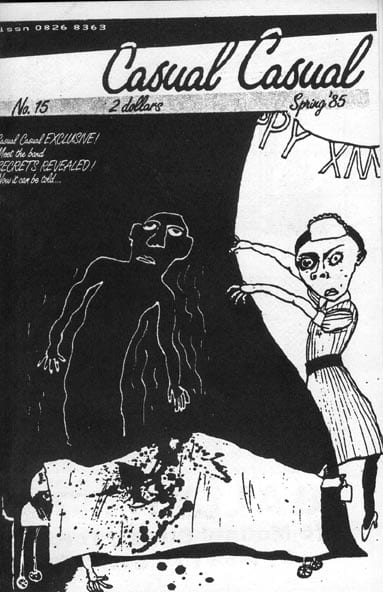

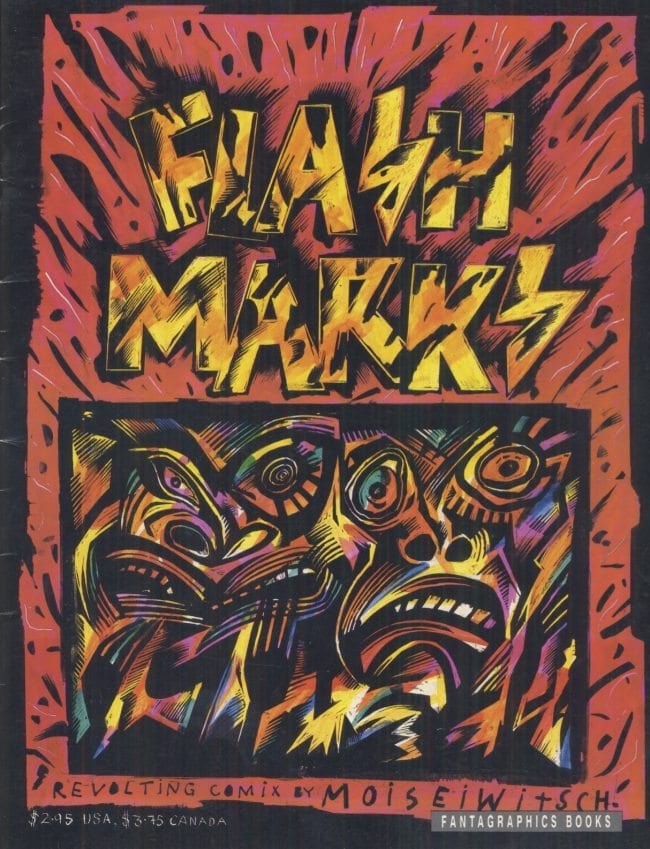

In your bio at the end of your collection Flash Marks, you mention that punk rock was a gateway into other types of art for you.

Oh, yes. When I got to Vancouver, the general function of art seemed to be comforting, decorative, pretty, beautiful … basically consoling. Things that would fit in nice in your office or next to a sofa or whatever it was, you know? That was still the idea. There was a certain amount of class. Then suddenly there were these punk posters up and zines around. I thought, “Wow! This is it!” Just fantastic.

Do you remember the first poster or zine that you came in contact with?

I don’t actually, but they were always in the street. I was working for sort of an anarchist newspaper called Open Road. It didn’t pay me any money, but I was doing art and comics for them. Those flyers were in there too and I just — I don’t know where I first saw them. I just don’t know. I might have gone down to Seattle and seen The Rocket. That’s the newspaper where I saw an ad for a comic contest. I had started making comics, but they weren’t the kind that you could put in the Sunday newspapers. I sent one in though, and the prize was selecting a tape of your choice. I won and got a tape of the Amadeus soundtrack.

So you had already started making comics by this time in the early ’80s?

Yes.

Did you make a transition from painting to comics?

I was still doing them both. I’ve always done both. And I was getting more involved with the newspaper and those people. I was also originally very involved with the women’s movement. I was doing a lot. I was a punk rock anarchist feminist. Very … out there.

A few of your shorter comics are about modeling. Are those autobiographical at all?

No, not at all. I used to look at the old magazines and sometimes they had these sort of photograph comics in there. They were very cheesy and looked so dumb. They weren’t about, or they didn’t include, any women I was interested in, so I think that’s why I wanted to make a joke about those. But I’m not sure what I’m talking about because I haven’t seen Flash Marks in ages. [Laughs] Maybe I’m still right.

After Open Road and The Rocket, where did you start getting comics published? Was your next one in Rip Off Comix?

Well, I also did some for The Stranger as well, when it was just a struggling little newspaper. But The Rocket used to get me to do more comics and illustrations and things like that. Then, the guy that ran The Rocket [Bob Newman] moved to New York and started working for the Village Voice. He started getting me gigs over there.

Oh, OK.

I also moved back to London at some point in there. And I was already doing some work for a newspaper here — a very mainstream newspaper called the Vancouver Sun. They used to give me work almost once a week.

You were doing editorial illustrations for them? Ones that accompanied articles?

Yeah, and sometimes they were humorous articles and sometimes they were very straight articles. I was always trying to come up with unique angles. Eventually I was fired.

Why were you fired?

The new editor did not want “that woman” in his newspaper. [Laughs] I was proud of that because he was a wretch. Very rightwing.

I can’t imagine your art accompanying normal everyday newspaper articles.

The guy who gave me the job was always trying to hustle for me and give me work, but I didn’t always respond well. He finally left, so I didn’t have anyone in my corner. And the new editor, I loathed him. But I think I did some work for them for about ten years.

Stopping by Seattle to do work for The Rocket and The Stranger, is that where you met Pete Bagge and got into Weirdo?

Yeah, that’s where I met Pete and all those guys. Dennis Eichhorn would sleep on the couch in the office at The Rocket. I met him and that’s when I first started with him too.

How did you get involved with Wimmen’s Comix?

That’s a good question because I’m not sure about that. I guess I was doing Twisted Sisters, so they asked me to do it too. A lot of the people in Twisted Sisters had a show in L.A. at La Luz De Jesus … is that right?

Yeah. The art gallery.

That’s where I met Aline and Robert Crumb. All sorts of people. The guy who does Zippy the Pinhead and his wife, Diane. That was really cool and it all snowballed. I don’t know how it all happened really. [Laughs] I remember that I worked with Fantagraphics and they were amazing to me. Very supportive.

Were you working with Gary or Kim?

Gary — who I think I met at Pete Bagge’s. We mostly talked on the phone and I would send him work. I don’t … mmmh … I don’t really remember a lot about this time …

Why’s that?

Around this time, I have to admit, I have an older son who became very ill with paranoid schizophrenia. He was living on the streets and going quite crazy. So I was kind of sidelined by that for a few years and lost a lot of my … direction. It was all very sad.

This was in the mid-’80s?

Yeah, early and mid-’80s. That’s when he was getting very, very ill. So that became my main preoccupation, as you could imagine. I used to go around looking for him on the streets and things like that.

Was this in Seattle or Vancouver?

Vancouver. My art took a backseat, but I was still doing some work for the Village Voice at that time. I was doing a little of my own work. I went back to England and then lived there for about five years. In England, they were much more accepting of my style in the regular magazines.

Why do you think that is?

Why? Well, I think Vancouver was still a provincial town. But the English have a wider, more diverse taste for drawings and paintings. They like all kinds of stuff and aren’t so snobbish. The Vancouverites were all descending into conceptual art. I feel like it’s been in that tight little box for several decades now. Very little of the stuff has any impact unless it somehow makes it into a mainstream gallery.

When you were doing work for Wimmen’s Comix and Twisted Sisters, did you ever feel the tension between the two? There was a decent amount of bad blood between them.

No, I wasn’t aware of that at all. [Laughs] I carried on regardless … from my icy post in the far, frozen north.

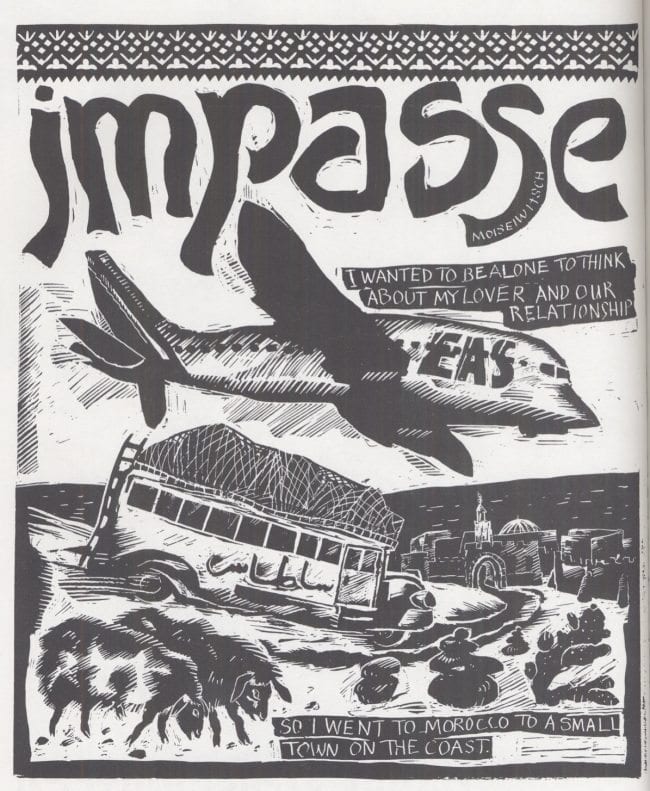

In Twisted Sisters 2, you have a story called “Impasse”. The story is set in Morocco …

Yes, I spent quite a long time in Morocco. I was very influenced by the French bande dessinée after I spent some time in Paris. I loved the French cartoonists’ work and thought their drawings were so incredible. I was very influenced by the French graphic artists. Someone said to me, “Why don’t you just do an autobiographical piece, since you never do that.” I used to just find stories and newspapers and things like that. But I thought, OK then, so I did that one.

Was that story done with etching or some sort of stamp-making?

I was using scratchboard with razors.

That style seemed to be way more popular amongst artist in the ’80s and ‘90s than it is now. You did it so well, and Penny Van Horn, but you don’t see it too much anymore.

Right. It’s seemed to have fallen out of style. One of the reasons I don’t use that style anymore is because I can’t get the good scratchboard anymore. I used to get that from England and it was really good. I can’t get the right ink because it’s all acrylic based now. It just doesn’t look right, so I had to give it up and I was really good at it. I tried looking for all the materials in England. I tried ordering it. It never worked, so I just gave up. It needs to come back! It’s a good medium.

In “Impasse”, the story's all about anxiety and issues regarding commitment. Are these things that you still deal with or suffer from?

Good question. That certainly is true of me. I finally met the guy who is able to withstand my anxiety and I’m still with him. [Laughs] He’s a very brave man.

Does this anxiety stem from art or …

Just life in general. The art scene has contributed to it though, especially in Vancouver. I just couldn’t stand it. And I’m also always involved politically, so sometimes I get a lot of harassment for that. I still do my own work, but I stopped trying to show it and just stopped … just stopped.

Did you ever feel like you were part of an art scene? Or always outside those scenes?

I was somewhat involved. Not that involved, but somewhat. I really liked that I was welcomed to comics. And those women and guys, I liked them. It was really fun to get involved, because I felt a bit rejected after trying to make it in Vancouver. In London, when I lived there again, I started to get somewhere, but my son became ill, so I came back to help him. I lost that momentum. I’m really just a loner, though. An outsider.

Would you consider yourself an outsider artist?

No, I’ve had far too much art training for that. But I’m an outsider person. Apart from my partner, I live in solitude.

I want to circle back to Dennis Eichhorn. You met him while he was sleeping on the couch at The Rocket office?

Yup! At least I think so.

How was your relationship with him?

I just loved his stories. I would tease him about them and tell him that he was making them all up. He would say, “No! No, I’m not!” I would say that they were just male fantasies and he would say, “No they’re not!” We had a good relationship. We had fun with one another.

Your first story in Real Stuff was “Fatal Fellatio”. That story is just stunning. How did you go about designing those layouts? The pages are so strange.

It was just one of those things where the inspiration fell out of the sky. Dennis told me the story and I just drew it.

You definitely used your fine art background to layout and design that story, right?

Oh, absolutely. Once you’ve been trained to do something, you can’t not do it really. I had also read up on psychology and things like that, so I had some awareness of psychological relations. And then, of course, there was always the feminist analysis I brought to things. I just went in that direction when I was drawing for Real Stuff. I always gave Dennis a hard time whenever I drew stuff for him or when we talked about comics. He was always trying to pitch me a story then tell me what I should draw. That’s not the way I’m going to do it. I’m always going to do it my way. Sometimes he’d like that, sometimes he wouldn’t. More often not. I didn’t want to have to do his stories the way he perceived them.

He wanted panel-by-panel breakdowns?

In a way, he was more visually conventional. If I’m going to do a story, I’m going to go in with my view of it. I don’t just want the images to reiterate the text. I want to add something. Writers in comics often just see the illustrator as a decorator for their text. Most magazines treat illustrators that way too. I like when illustrators undermine the text or oppose it, not just reiterate what’s already in there like the readers are dumb or something.

Is that irritating?

Yes! It’s very boring. Go get a robot to do that.

The subtitle of Flash Marks is “Revolting Comix.” Do you think your artwork is revolting?

Yes, and more! I want my art to be revolting in terms of the verb and the adjective. Revolution and revulsion.

Most of your work is in stark black and whites. What attracts you to those colors?

I’m a very black-and-white person. I love the drama it creates. I am influenced by the German art that was made during and after the war. Those woodcuts and things, that were very expressionist. Very spare and expressive pieces of work — I like that. I’m not interested in highly-rendered art or high realism. I’m not really interested in that.

How about someone like Ralph Steadman?

Yes, I’ve met Ralph and I like his art very, very much. He’s a great guy and I absolutely love his work. He was influenced by Ronald Searle, who is my favorite illustrator ever.

When I view your work, Francis Bacon also comes to mind for me. That intensity …

Francis Bacon! I used to meet him in the pub when I was a student in London.

You knew him!?

Oh yes, he would buy drinks for everybody. He was kind of outrageous. He and I did a drawing together one time. I loved Francis and I loved his paintings. They were a huge influence.

Whatever happened to that drawing?

I don’t know that. We were quite drunk. [Laughter] Francis was a very generous and sweet man. He would buy us drinks and we were so broke. He’d come in and “drinks all around, Francis just sold a painting.”

In Flash Marks, there’s a story called “Coke’s Progress” about cocaine and its effects on people. Were drugs around you at that point when you drew that? Is that something you know about firsthand?

Yes, I used coke and a lot of my friends did as well. But I had enough of messing around with drugs. It made me too anxious. Incredibly anxious. But me and my friends knew that quite firsthand, unfortunately for some.

You saw a lot of people go down?

Yeah. They either went crazy, or died, or got horrible illnesses. Just terrible.

I was looking at your piece called “Strategies for Survival”, which is the women’s magazine cover parody …

Oh, right. The one about women artists.

Yes, yes. You have that line in it that goes, “Will she leave art or will art leave her?”

[Laughs] I always wonder that. That pretty much sums me up.

I was thinking about your era of comics and how many fantastic artists just drew for a couple years, then got out completely. Or ones that went into fine art and never made comics again. Why do you think that time period of the late ’80s to early ’90s had so many artists like that?

It’s not fruitful and it requires such hard work. Also everything became kind of corporate. It’s very hard to survive in that kind of atmosphere. Where I came from — London and Paris in the ’60s — you could go there and draw, record music, and create art, then shuffle around to the cafes and have a drink, meet up with friends, write poetry, or whatever it is you wanted to do. People took you seriously without you having to be famous or successful. You just had to be true to yourself. But now it’s like if you’re not famous or successful, you’re nothing.

Can you recall when that changed?

It’s when corporate values became dominant. And the internet doesn’t make it any better. It’s the same for music and television and all media. Now artists all have good teeth and good hair.

These cartoonists in Wimmen’s Comix and Twisted Sisters who never made comics again — do you think there was an issue with women too? That you weren’t as welcome?

I really don’t know. I really don’t. For me, I felt that comics became a dead end. You’re never going to make any money. I wasn’t sure I could commit my whole life to doing that. I just felt like exploding into the opposite direction, so I did huge installations. Massive ones. I found taking up entire gallery walls way more gratifying in a way. Can anyone do one thing for their entire life now?

I don’t know. [Laughter] Do you think there were more open doors in the fine art world than there were in the comics world for you?

It’s much easier to get sucked into the art world. It’s very seductive. People are a lot more reverential towards fine artists and really in a way they shouldn’t be. There are a lot of shitty people — very tiny, self-absorbed, and boring.

You’re talking about painters?

Artistes. It’s very serious, you know?

Right. Art with a capital “A.”

And with an “e” at the end. Artiste. Those people. Competitive snobs. So weird. It seems to me that in political activism — not comics, not fine art — people are much more friendly and real. I’m much more comfortable in a group of activists than I am in a group of artists.

When did you become active in political and social issues?

When I was a student in London. I got started with the CND — the campaign for nuclear disarmament. Massive marches against nuclear weapons. Huge marches in Hyde Park. I ended up doing a lot of traveling in the Middle East — North Africa and Palestine. I saw what was happening there and came back and started doing drawings, paintings, and photographs of what I saw there.

When did you start traveling like that?

When my kids left or went to university. I think somewhere around ’89.

What called you to the Middle East? Were you going as a tourist or an activist?

I wanted to know what the hell was going on in the world. Get out of my comfort zone and go and see everything.

Getting out of your comfort zone can be hard to do.

I think it should be mandatory for everyone to do it. Maybe even once a week, if not once a day. Don’t you think so?

Yeah, I do think so. Traveling seems like it may be more difficult now in terms of expense and other hassles.

Yeah, yeah. If you went to some of the places I went to now, they might not let you back in again.

Right.

It’s very strange now. You’re right, it is a lot harder to do that.

I saw on your website that you did some activism work in Mexico as well?

No, I don’t think so … oh, yes, I took some photographs in Oaxaca of street art when the uprising was going down. I took some photographs of the graffiti.

Have you ever made any street art or graffiti before?

Yes, I’ve done some stencil stuff and banners. Yeah, you do a small thing on a wall and off you go. I’ve made stencils for people.

Do you think street art is politically important?

I do. The streets, the walls, those are some of the last free places, aren’t they?

How do people react to your art when you’re traveling around the world? How did they react in the Middle East?

They hardly ever saw it. I would take sketches and then make the final pieces when I returned home. I’m sure some people thought I was a bit strange because I had very, very short and bleached hair. I was quite thin at the time too. Most people didn’t know what to make of me, this thin punk drifter traveling on my own and looking so strange. They didn’t know what to make of me at all.

Did you ever get in touch with other artists in the Middle East?

No, not really. Hardly ever. I went to museums and saw a lot of stuff that would influence my own work, but I didn’t meet any other artists. I didn’t know anybody. I was usually wandering around on my own and you can’t really initiate conversation, especially with guys or anything. The women wouldn’t talk to me and I couldn’t talk to the guys. When I approached men, I got the feeling that they thought I was trying to fuck them. It got lonely.

How did your work and activism for the Palestinians begin?

Just by being there. And coming back and thinking about it, drawing it, and reporting on it.

And people were receptive to your stories and what you witnessed when you got back to Vancouver?

Well, I don’t know if you know anything about this scuffle, but the press have been … colluded. They aren’t really writing all of the truth of what is happening between the Palestinians and the Israelis really. There was a young woman who came from Olympia, Washington named Rachel Corrie who was killed trying to protect some houses from being demolished. We were there at the same time. I was there when she was killed. Have you ever heard of her?

I have.

Yeah …

[Long silence.]

I was just remembering that. So, I just felt like I had to do this. I had to go back and say what was going on because there’s nowhere to read it. It almost gets completely deleted from the mainstream press.

Mmmh … news gets deleted altogether or diluted?

I’m not sure I should get into this conversation.

OK.

It might … offend you.

You made a sort of parody newspaper in Vancouver.

Yes, and that was exactly about the newspapers and especially the Vancouver Sun, who I used to work for. The person who owned them at the time had an actual editorial policy to not write anything negative about Israel and the issues surrounding it. So, me and some others made a parody newspaper and wrote negative things about Israel. We got clobbered and got sued.

Wouldn’t that be protected though? I’m sure it didn’t cut into their circulation numbers. It was a parody, right?

Well, yeah, but at the beginning all that stuff falls to the side and they can try to lay the law on you for anything. They didn’t care about the finer niceties of the law or how that power should be used. But that was argued in court. Anyway, the owner of the newspaper eventually went bankrupt and the case never got resolved … I guess it’s resolved now, but it’s kind of in a coma.

A coma?

That’s it. It’s in a coma. No one’s had their just desserts and the case isn’t resolved. So we were going to ask if so many thousands of dollars could be put aside during his bankruptcy, that if he wants to start it up again, we at least know he has the money to reward us. But they weren’t going to do that. They were just going to go bankrupt and refused our request for money. It’s in some strange legal limbo.

And you’ve done some activism at home in Vancouver as well?

I worked with people with mental health problems and drug issues and did some work at shelters. That’s because my son was ill and we had a very hard time getting him diagnosed and treated. At the time, it was very difficult. It’s much better now. I wanted to tell people about it. That these cruddy, stinky people they see on the street weren’t necessary lazy or anything, just very ill.

Do you think art is the best form of activism? Is art a form of activism at all?

It can be a form of activism, but there are many different forms. I went that route because I’m better at art than other things. I’m not very good at giving speeches, but I’m good with images and things like that. So I do that.

Do you think artists have a responsibility to speak out about issues that affect them or …

Yes! I do think that.

So you think that artists who aren't involved socially or politically are wasting their time?

I don’t know if I would say that. I guess there’s a great need for some people to look at pretty, consoling pictures that they can put on their walls. There’s enough room for everybody. [Laughs] I don’t know if I actually believe that anymore. But you know what I mean, right? There’s a lot of people who do that kind of work and may they be successful. It would bore me.

Those people making pleasant paintings tend to be better known and make more money than the artists using their platform for activism.

Oh yes! [Laughs] But we don’t really need that much money, do we?

Well, I don't know.

We just need enough to get by. Pay the bills. Pay the rent, hopefully.

You were teaching a while in Vancouver too, right?

Yeah, I was teaching at the Emily College of Art and Design. Yes, I was.

What courses did you teach?

I mostly did drawing courses. I also taught a comics class. Things like that. Mostly just drawing. I used to teach it to animators, sculptors, painters.

Did you enjoy it?

I did. I really liked it. I’m actually quite good at it, but I didn’t like the politics at the school. Most of the people teaching there were stuffy professionals, tenured, didn’t lead discussions at all. They just talked down to the students. I used to have waitlists for my classes.

Do you miss it?

No. [Laughter] Such a pain in the ass. But it was really interesting. It’s very interesting to have to explain drawing and break it down.

When looking over your art, I noticed that you signed a lot it with your name, of course, but other pieces with “Xero.” X-E-R-O.

Yeah, X-E-R-O.

Where does that come from?

It’s an old Chinese tradition to change your name every so often for artists and poets. It’s so you can’t ride along on your reputation.

So how many times have you changed your “art name?”

I’m on my third one. [Laughs]

I have never heard of anyone doing that before.

Haven’t you? Oh, OK.

I think a lot of artists want to ride on their name and reputation after a while.

But it’s bad for you though. You just start repeating yourself and doing what you’ve always done. It stops you taking risks. Galleries are the worst like this for artists, I think, unless the artist is really fucking brilliant.

Galleries are the worst?

A lot of them just want to sell. They want to create a reputation for themselves and they need pieces to sell to do this. So they get artists to just crank out shit and then they sell it. They just want something they can rely on.

How long does it take you to complete a piece? Sometimes your paintings and comic pages look like they’re done at a feverish pace.

Yeah.

Is that how you work?

Yes. I don’t do very much planning.

And it’s the same for your comic pages and your big paintings?

Right. It’s hard for me to sit down and plan. I’m impatient. And that’s something in art and comics that people really admire. People like art that looks very careful. They like when an artist seems like they worked very hard and took a long time.

That illusion that things are better if they look like they took a long time.

Yeah, that’s it. People want artists who try hard. Artists have been traditionally seen as people who get away with murder. So, at least if they worked hard on a piece and took a long time, people have something they can respect them for.

That’s all based in capitalism, isn’t it?

Could be. Good old work ethic.

The last comic you made was called “This is a True Story”. That was in a journal published by Duke University. How did that come about?

I really don’t know how that happened. They just asked if they could use it.

It’s a huge shift in style for you. It’s almost unrecognizable from your older work.

Yes.

It’s much cleaner and the pages are left white and wide open.

Yeah, there’s not very much black. Who can tell why I chose to do it like that or what the inspiration for it was?

Did you think that it would best fit the story?

I was just looking for something new, and by then I couldn’t find good scratchboard. I supposed it’s also supposed to look like a kid’s story.

Like a children's book?

It does look like that.

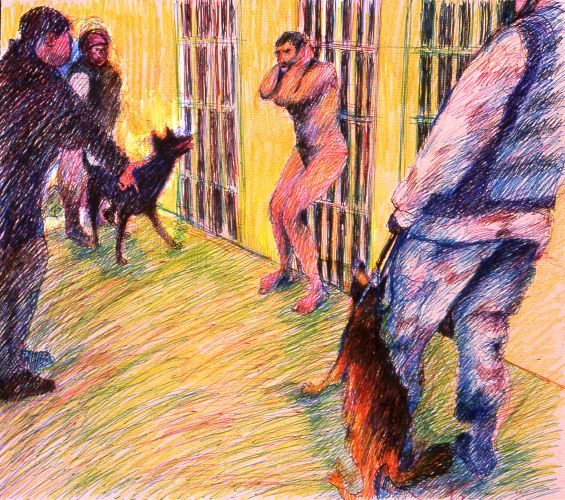

I saw on your website the Abu Ghraib drawings that you did too. Those look like they’re done in colored pencil.

Cheap ballpoint pens on plain white paper. I wanted to use the cheapest material possible. I love ballpoint pen. It was a fun experiment, but the scenes are harrowing.

What do you make of the current political climate?

It’s awful. I mean, you read all this stuff about the destruction of the environment. It’s so mindless, so wretched, and so awful. I’m so ashamed that this is happening. But it’s happening all over. I live on a mountain and see the destruction and living creatures’ habitats getting destroyed. Ghastly. And just the number of living creatures on this planet is dropping. We’re just destroying our fucking planet. It’s dark.

Is environmentalism something that you've touched upon in your art before?

Somewhat. But it’s such a huge subject that I usually don't know where to start. I’m kind of circling around it right now.

How about your art right now? Are you working on anything currently?

I am. I’ve got a very small space — I don’t have my lovely studio anymore since we moved — so I’m doing quite small pieces. I’m using gouache and doing images of extreme weather. I’ve experienced a lot of that here. I’m not sure what’s going to come from it, but that’s what I’m doing.

Any hope that you return to comics at all?

I’d like to. I have to say that Trump is very tempting.

Like doing an editorial cartoon?

Oh, I’d like to do a bit more than that! Everyone thinks people like … Stephen Colbert are so outrageous. [Laughs] He couldn’t even get in the kitchen with me and my art. Things need to be said, but in a slightly different way. And I might do it. The only problem is that I’m frightfully ancient now.

You’ve still got time to make more great art.

I hope so.