There are two oft-repeated statements about Carol Tyler (well, at least they're oft-repeated in my house): 1) She is an AMAZING cartoonist; 2) She is WAY under-appreciated.

The latter might have changed – at least a little bit – with the release of You'll Never Know, Tyler's three-volume epic about not only the trauma her father suffered during World War II, but Tyler's own relationships with her dad, with her teen-age daughter, and with her husband, the equally great cartoonist Justin Green, who, as Tyler portrays it, abandoned both wife and daughter for another woman (spoiler: they eventually reconciled). The books not only deal with such weighty issues as PTSD, family strife, loss and death, they highlight Tyler's utterly unique sense of color, compositio,n and storytelling chops.

With the release of the third and volume not completely out of the rear-view mirror yet, I thought it would be the perfect time to talk to Tyler about the work as a whole and how it came together. As Tyler recounts below, the third volume's production came at such a difficult and traumatic period in her life that it's only recently she's been able to even begin to assess the book's merits and failings.

I talked with Tyler over the phone back in February. The interview was then copy edited by me and Tyler, who added and expounded on a number of things I had misheard or mistyped in my haste to get everything down. I'd like to take this opportunity to thank her for her time, honesty, and generosity.

Chris Mautner: How does it feel to be finally finished with the project? Relieved? Sad? All of the above?

Carol Tyler: All of the above and more. I still can’t believe I’m done. There was so much turmoil in the last year and a half of putting the last book out. I finished it in tandem with a tremendous illness in my family.

The first book, I started it in 2004 and it didn’t come out until 2009. I started putting the [second] book together right away. I didn’t want to lose momentum. I had most of Book Two done when Book One came out. Nothing came out in 2011, because I really needed a little space of time to make sure I was attacking the ending [properly] and tying up any loose ends. I wanted to work on the transitions and storylines and narratives to make sure they made sense.

For [the third book] to come out by Fall 2012, I needed to have it delivered to Fantagraphics in the beginning of the year. As I was pulling it together, my mom got sick and went from the hospital to the nursing home to having hospice at the house. At the very same time, my sister, who was my tag-team partner over the years in caring for Mom & Dad, ended up with a stage four ovarian cancer. Awful.

Both my parents and my sister live clear across the state of Indiana from me and this came about while I was teaching comics Fall Quarter at the University of Cincinnati. So I would teach class, get in the car, drive four hours to the nursing home or stop at the house to take care of my sister’s husband, who has Alzheimer’s, or my niece who has Asperger’s. I’d have the pages in one hand, a seasonal bouquet in the other, ink in my purse, and I’d be running back and forth. “Hi mom how are you doing,” then grab her bedside table and start lettering. I literally had to do the back end of Book III in hospitals, nursing homes, at the chemo place and in waiting rooms. It was insane.

My sister’s illness — our family was blindsided because she always took good care of herself. She didn’t smoke or drink, but ovarian cancer doesn’t care about those things, apparently.

My sister started chemo in December 2011. My mother died in February 2012. I got the book done in May while mourning the loss of my mom and dealing with my sister’s cancer treatments. As a result, the book has been barely on my radar screen because it’s the characters from my book who are in trouble and I care mostly about them as living beings. (My sister has cameo appearances here and there.) These women were my best friends during the making of these books. They were 100% behind me all the way.

That sounds horrible. With all that going on, no one would have criticized you if you put the book on hiatus. You could have taken a break.

Oh no. I’ll tell you why. The rumor about me for years had been, “Tyler isn’t serious. Nice start years ago but she doesn’t work that much.”

Justin [Green, Tyler’s husband] had his sign business and his comics deadlines and so the bulk of childcare fell on my lap. When parenting, as you know, there’s that immediate pull for your time, especially for Mom-eee.

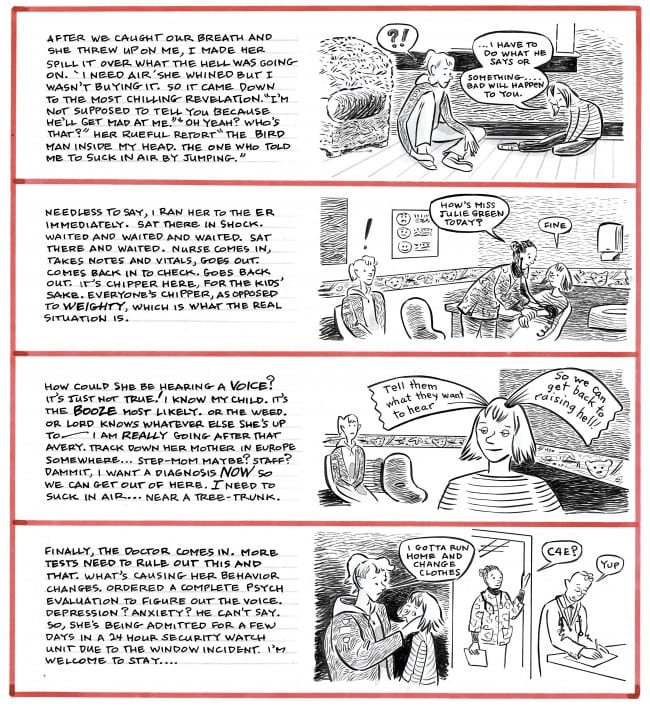

And, in the story I tell [in You’ll Never Know], how he left us and I moved across country to reinvent myself. I had never been to Cincinnati before. I just came here on impulse. My daughter went bonkers after we got here. She got the OCD gene from her Dad. It took awhile to figure out and diagnose. Many years of therapy. The bulk of her breakdown fell on my shoulders to deal with, and I gladly bore the weight because I was the one who yanked her out of her California life.

Women cartoonists with kids get to a certain age [where their kids are a little older] and can jump back in almost full time. But due to my marital drama and her OCD treatment, I didn’t get back to the drawing table until she went off to college. Then I had some quiet time and space.

The thought of having a reputation of not being a finisher, though, that has never been OK with me. I was always very committed to my art. People say, “Damn, don’t you take a day off?” Nope. I’m a hard worker. The idea that anything could stop me? Nuh-uh. Not ev-ah. I was dipping a pen at my dying mother’s bedside. Can’t get more committed to the craft than that.

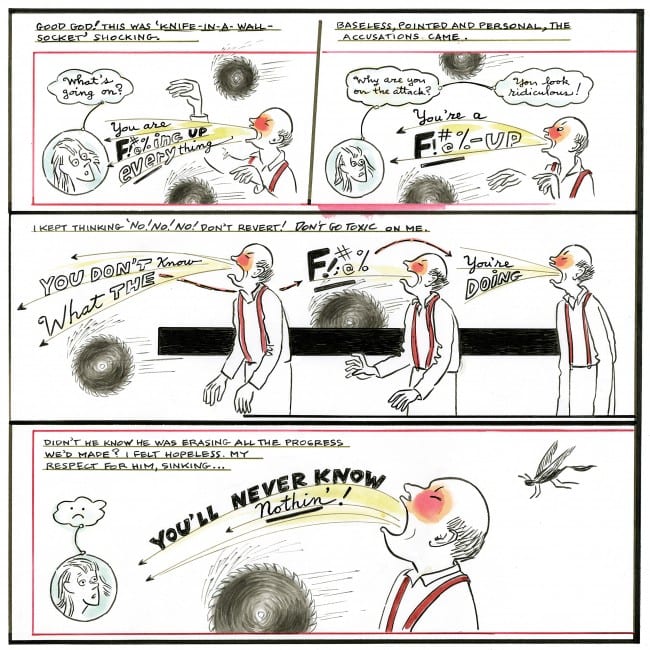

In the story I talk about my dad’s crankiness and our relationship difficulties, and in real life he acted very shitty at the end of my mother’s life. His negative energy was part of the fuel that helped me in a weird way. He’d rail on me, I’d come home and would add an extra page or two in order to turn up the dial on his being a jerk. In Book Three, I drew him hurdling saw blades at me; that’s straight out of his behavior. He did talk like that.

How long from beginning to end did the whole project take you?

Eight years, with life sprinkled in between, as I earlier described.

I’m a binge worker. I’ll stay up all night and sleep days for two weeks and finish ten pages knowing I’ve got to go to Mom and Dad’s for the weekend. I always did it in clumps or clusters. I just had to pull the clusters together.

The other thing I did was if I was working on a page I said to myself, “Tyler you could do it that way, but what if you challenged yourself and put the figure on this side and how could the word balloons be reconfigured from there? Would it give a more exciting result?” I was always trying to up my game a bit.

Can you give me a concrete example?

Somewhere along the line someone said to me, “Oh when you have two word balloons in a panel, never crisscross the tails with one another. Show where they’re coming from and leave it at that.” In the books, Dad has an X on back from his suspenders and I have an X pattern on my jacket. So when Dad & I get more intensely agitated toward each other, I would crisscross the balloon tails to match the X of the suspenders and the jacket.

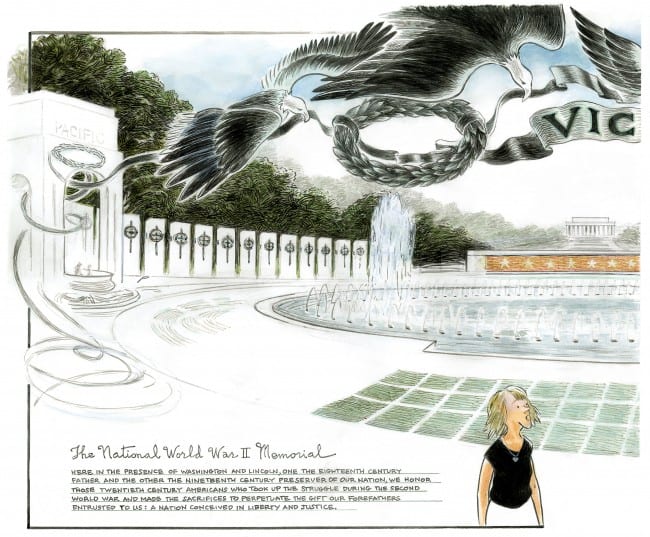

There’s a part at the end with the WWII memorial. The entire space is so grand and was designed with circles and ovals as a motif. So I thought, “How can I maximize that? How can I use the motif?” There’s the flatness of the page, but you can imply depth. Can I do something with that? That was a formal thing that came to mind that I challenged myself with. Then it was, “How do I work the mood?” Funny thing, I pulled the plug on color as it nears the end because I wanted it to feel like the energy of the story was subsiding. I wanted the reader to feel the ebb.

Can you talk a little more about your use of color in the books?

I started doing comics in black and white, for Weirdo, 'cause that was the only option back then. Turns out that was good because along with tonality, I needed to understand all the comic-book stuff – the arc of the story, timing within panels, dialogue, the lettering. I had to learn those structures. If you remove color as a factor, you’re removing this giant thing, which for me, a painter, had been the main conduit for all sorts of non-verbal things. It’s like color is this whole world that gives you moods and suggestions. So I was dealing with the bare bones, the mark itself, how to shade things with cross-hatching. It took several years, fiddling with that. Then when laser scanners came in, it was like, “Are you saying I can use color pencil or a watercolor wash? Wow.”

Working in black and white all those years taught me about weight. I don’t exactly know how to explain it. You put a light green up against a rust color, there’s a difference in weight. The colors have different meanings, as well as what happens chromatically. In the “kid crisis” part of Book Two I used red panel borders, thinking, “Let’s get down to it, let’s get simple.” When there’s a crisis, you focus on the crisis. I made it stark in order to have the reader focus. In a couple of other places I did that too. Just focus in.

I don’t know if you noticed, but I do things with the panel border too, that informs speed and weight, because I’m concerned about depth and solidity and anchoring things together. These are conscious decisions that seem to have more to do with dimension, sculpture and architecture.

I used 53 colors. I counted them one day. I had maybe a dozen shades of black. Not all blacks are alike. There are grays and tan-colored grays and variations on variations. I mixed it by hand and put it into little crafter’s containers.

Sometimes I was surprised by the colors of "normal" things I would take for granted like sky and grass. I was trying to tweak it and finally I was like, “Duh, grass is green, just put green down.” Even though I was tempted to tool and retool, some shortcuts are no-brainers.

I have to say, what you see printed in the book, though, is not at all what the original pages look like.

No?

Absolutely not. And I didn’t notice it till Book Three. I had to open Book Two to compare the original page to the printed product, “Why is paper so friggin’ white?” I called Kim [Thompson] and said, “Dude, there’s something about the book I don’t like.” The white pages killed all my fussy little color subtleties.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m very proud of the book. It’s beautiful to look at. But sometimes the printed blacks are too dark or the browns dominate or there’s too much blue. There was never a chance for me to work directly with the printer in Singapore.

It was all done digitally. My originals never left the house. I scanned the art and corrected it at school. I work at a big-assed design school with expensive, state-of-the-art machines. Fantagraphics has good [scans] too. But something happened in the printing. So when you say the book looks exquisite, I think, “If you could just see the real art.” You can like [the book], but know the original art is better than the pages.

A perfectionist is saying this. I’m talking about difference between cousins ecru and eggshell. I’m saying this as a person who created the book and who will fussbudget over every shade and tint of color. As it should be.

You may know that my master’s degree is in painting. People always said to me, “You have such a thing for color.” I understand it on a cellular level. I understand color beyond belief. How come I’m so keen on color? Where does that come from? As a baby I was told to shut up a lot by older siblings and [was not allowed] an opinion whatsoever. I did have coloring books and in them I did work on nuance and did sophisticated work for a kid. I’d take one type of purple and put orange over it and see what that did.

I could tell you that the Beatles poster was a certain type of red that was different from the kind found on a bubblegum card. I always had a gift to point out that, say, a certain car had the same color red as that on the Special K box. It’s not cherry red.

There are things about the printed book layout-wise that … I could have improved on. That’s OK. I could have extended that line a little bit or moved this over a quarter of an inch. An artist is never satisfied with the results. Overall, yeah I’m proud to say I worked on it. I told the family from the beginning, “Don’t expect perfect likenesses. If I have to stop and do a full portrait, it will never get done. These are cartoon representations of our interactions. They’re not literal, visual characterizations.”

The books have a loose, improvised feel. Was that by design? How did the books take shape?

One of things I realized in making the book is how intuitive I approach everything. The knowing part is “game over” for me. I like that I “sorta” know [what I want].

This is how I describe it [while I’m working]: “OK, in this page thingy comes in and this thing goes 'bloop,' and all right, boom!” Does that make any sense? No. But I know exactly where I have to weave the whole thing together. The biggest surprise was having to work on short sections and being interrupted so much I didn’t realize I didn’t have a solid way of connecting the various sections that didn’t seem flaky and fragmented.

For example, I knew what I wanted the ending to be, but I didn’t know how to get there. I just knew that at the end [my dad] is crying at the memorial. But I’ve gotta get the reader to understand how important that moment is to the book’s overall theme.

Even though I wanted to talk about me and Dad and our differences and World War II, I didn’t know how deep I was going to have to dig. I started scrawling notes on this giant white sheet of paper on a wall but it wasn’t big enough. I ended up with miles of material.

I initially thought, “I can do this book in 80 pages. I can make the entire statement and then sit down and explain Dad’s bout with cancer, which shows he has fortitude and stick-to-itiveness, which is an underlying theme, but the cancer part would need to be fifteen or twenty pages – so much for an eighty-page book.”

Clusters. I did what I would do if Aline [Kominsky-Crumb] called and said, “I need a story for Weirdo.” I was doing what I knew, which was how to knock out two or five or ten pages. Then I just had to manage the clusters.

The thing that clicked was the idea that I wanted to tell the story of when Justin left. I wanted to simultaneously work through the personal hurt that occurred and talk about the hurt to Julia. I thought, “Tyler, you don’t just want to tell Dad’s army story.” Because then it’s just a blog post. How many army guys’ kids have set up a blog? And if you read them it’s straight military stuff -- it’s someone’s story about the army. I had to find a device [to broaden the scope] and the device was the scrapbook. I could, in the story, turn to a project to have things make sense and the project would be the thing that tied everything together. I could explain the soldier stuff—that [my Dad] was a jerk because of the war—and about what PTSD can do to a child. It all started to become clear once I anchored it to the device of the scrapbooks.

Intuitively I knew where I was going. There was a whole bunch of stuff that didn’t make it into the book that has to do with Dad’s pain and me trying to resolve it. Being a Catholic. Ultimately that stuff doesn’t affect what happened. I’d have to say, “Is this is a cul-de-sac or does it bring me back to main point I’m trying to make?” At times, like in the first book it can seem like, “This is my dad, he’s a crazy dude.” I wanted people to see him as a goofy guy and happy-go-lucky and contrast that with the guy at the end, so they’d think, “Oh wait a minute, this is a suffering dude.”

Did you have any problems with your family members in revealing their secrets?

Not much. I asked my daughter. I said, “Honey, I am going to talk about you jumping out the window.” She said, “I don’t care, go ahead. My life is an open book.” We’re an autobiographical family. Anything you say and do will be in print someday. I said to them, “Listen everybody, I want to take our troubles to the bank.”

However, Justin was more uncomfortable. Mr. Autobiographical Cartoonist #1 himself! At first he expressed strong concern about bringing "the other woman" into the book. I said, “It’s not about her. It’s about us.” I am not in it for vindictiveness. I am dealing with truth and trying to speak of our greater humanity. I need to show all of us as flawed characters that need to triumph over our difficulties, otherwise we wouldn’t be human beings.

He just recently finished all three volumes. I said, “Do you feel like I did right by you?” He said it was a great book, but still, nobody likes to be depicted as the bad guy. He had to bear that outright, whereas with the rest of us, our crimes are more subtle.

Are you happy with how the book has been received? Do you feel like it found an audience?

Since I’m in mourning for my mother and pre-mourning my sister, I haven’t paid much attention. But when I do hear something, it’s on the lines of, “I read the first one.” Those who read all three are blown away and they usually take the time to tell me. That’s awesome.

I did make a Facebook fan page but I don’t update it.

Back in days of black and white, I called the people that followed my work “The Faithful 500” because I always felt I probably had 500 readers. I think now with social and traditional media it might have gone up to like 750. I might have 3,000 Facebook friends, but I’m guessing only a few of them have read all three books.

The sadness for me is that I made a major statement about PTSD that speaks to the generations and it’s just not getting through to the masses. I tried to be as clear as I possibly could with well-crafted pages and hip-shaking drama, but...

Kim suggested I start putting Carol Tyler [instead of C. Tyler] on the cover so I can make women’s lists. I didn’t do that for the last five years specifically because I didn’t want to be judged by my gender. I wanted people to connect with the book on its own merits. But I’ll tell you what – that glass ceiling thing is for real. And “Carol” is a 1950s baby boomer name that turns off some young people.

Here was a big part of my logic: I was going to write a book about my Dad and he’s C.W. Tyler. I thought, “I can be C. Tyler. It’s the C. Tyler book.” But I quit doing C. Tyler now. I’m tired of trying to out-psyche ageism and sexism. No matter how much lotion I throw on them, my wrinkles are not going away.

It strikes me that one of the big themes of the books is loss and trying to come to terms with loss.

Loss is a very big part of the book and I experienced loss while finishing the back part of the book. I think one of things I’ve learned this year... I’ve never seen anyone— I watched my mother die this year, being attentive to the end of her life, and now my sister’s got this disease. When I drew “The Hannah Story”, I had just lost my job. The emotion of loss is powerful and one of things I recently come to realize. You actually do go through a period of mourning that’s physical.

There were lots of other losses too. In fact, last year was the suckiest year ever! I had to put my dog down. You name it. All the worst shit you could deal with I had to go through. Everything from my house being robbed twice to my daughter’s car being stolen. Justin and I got invited to [Europe] and I got sick on the trip. Some weird virus that lasted two months. Twenty-two days of fever and being bedridden, unable to move. I had a reaction to the virus and ended up with reactive rheumatoid arthritis. I couldn’t move. It traveled around different joints in my body. Couldn’t roll over. Couldn’t walk. I remember when I could finally move my foot one day, “Wow. There’s hope.” After the fever broke, I had lost twenty-five pounds and weighed 119. This was in November.

Then this nice man Jay Stowe [from Cincinnatti magazine] called me up and said, “We have a space at the back of our magazine, the page before the back cover. I thought about you, would you like to do anything? Do you want to do a strip for the inside back cover? I looked up to the heavens and declared, “Thank you, Mom!”

This idea of 2012 ending with a call offering me to do whatever I want next year and someone having that much confidence in me as an artist – I was real happy when 2013 came.

So what are you working on now?

That monthly one-pager for Cincinnati magazine. I have the inside back page and it’s a series called Tomatoes, about trying to grow tomatoes in my diverse, urban neighborhood. Although I’m keeping it "light." No "crack-head screaming on the corner at 3 a.m." stories. I’ll save that excellent dimensional shit for Tomatoes the book, someday.

Can you talk a bit more about what you mean by “undefined”? Did you do a lot of revising and editing?

Whenever I had to add a page to the book it was hard. I’ll tell you why. For the most part the pages were set up to start left side of the page, often as spreads. It was very right page, turn to the left page dependent. If I had to add a page, that meant I had to put in a second page somewhere else. So it wasn’t easy. If I had an idea it had better by golly be worth tearing into my existing compositions. I had to get to the flow part down. I was often like, “Oooh, I’m not going to do that.”

I have to tell you this story about page five [in Book One]. I’d get some pages done and leave a spot empty. “Pick it up here,” I’d say. “I don’t know what page nine is at this moment. I’m going to do page nine later, and put it on the list [of things to do]. Oh shit, don’t know how I want to look,” and I deferred it for a year and a half. I gotta do that page, but I have no idea what I’m going to do.

I used Post-it notes and gridded stuff out on the wall trying to organize [the book]. Some pages I called transitional, the joint that connects the femur. You have to have something to connect this big statement with this big statement. Can you pull it off with one page? Should it be two? What speed do you want people to attack it with?

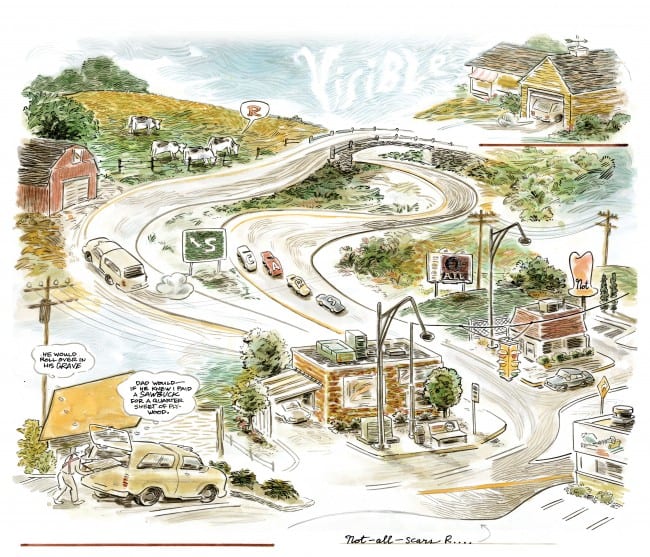

I was just about finished with Book One. I knew I had one other page to do and I went, “I know exactly what want to do with page nine,” and I did it in two hours. It was the one where [Dad’s] been at the lumber store and he drives the car home. I wanted the reader to go from the bottom of the page where he’s leaving the store. Why jump up to the top left corner of the page? Why can’t I have him [travel] up there to the upper right corner, which is going to be just as satisfying for the reader now to turn the page because they’ll have traveled up there with him.

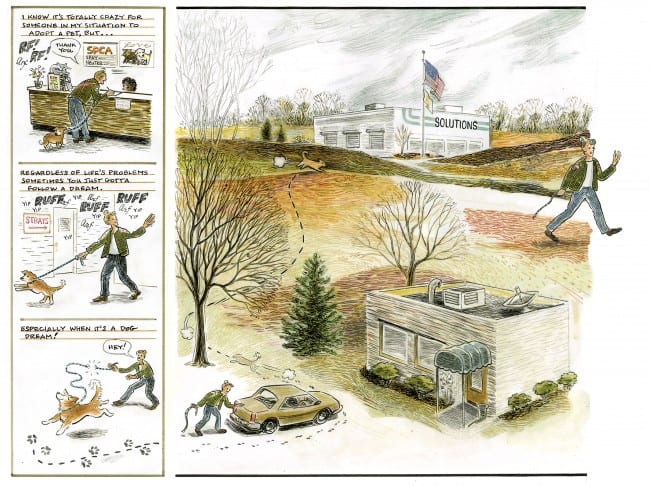

The message I wanted [for the book] was “Not all scars are visible,” but I didn’t know until that morning what I was searching for. I didn’t know how or when it came to me. I guess it was just inside. The technical thing was to go backwards [along the page]. I did that other one [in Book Three], where I am chasing the dog.

It occurs to me that with You’ll Never Know you’re offering a portrait of middle America that doesn’t get portrayed in comics very often.

It’s funny you say that. One of things I felt in charge of in doing this book was a time-and-place factor, in that I’m very painfully aware that the world I grew up in is gone. The Chicago I knew was gone. The Chicago my dad knew was gone. He used to talk about turning on the tap water and minnows would come out. That’s how clean Lake Michigan was.

I did want to show that [time]. I love the prairie and Americana and stories about the dust bowl. I love that era. Grant Wood paintings, I love that. I live in this heart of the country. I was born and raised here. I’m a sucker for the concept of the American experience. Life seems to be more intense now only because we have more information to process. The truth is if you pay attention to wherever you are there’s still a lot of local flavor. I wanted to sing about that. I felt like I was responsible to make sure that note came through. This is where we were. This is how it is in this place. Some people lived in this time and place and this is what happened to them. All great writers and artists nail down their place and reference it. Not sayin’ I’m great, but time and place are key to a good story no matter what.

I wanted that feel of – not the east coast, not the west, just an American place, without it being that icky flag-waving shit that has hijacked our culture. People think that the middle of America is like that, but it’s not. I really just wanted to show the gentleness of the ordinary, I guess, and how it's all subject to change. I think it got through.