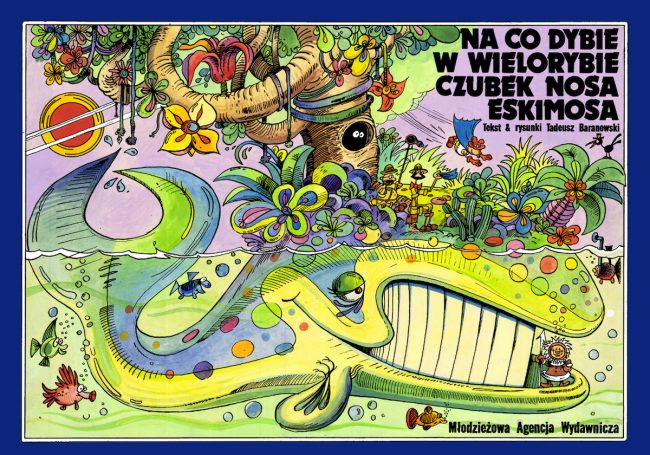

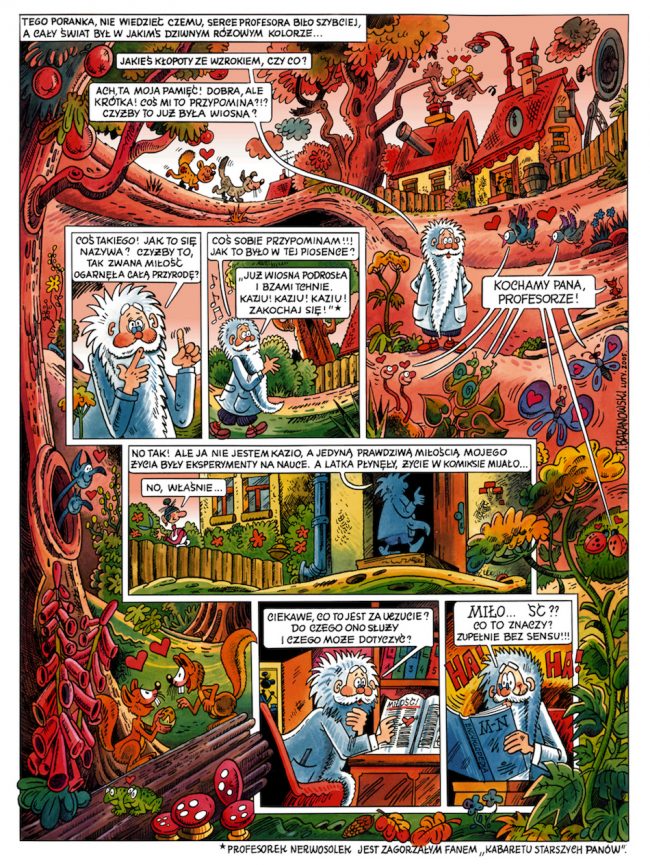

Tadeusz Baranowski (b. 1945) is a Polish painter, illustrator, graphic designer, comics writer and artist. He’s known for his absurdist humor, wordplay, and use of metafiction. After graduating from the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, he started working for the “Świat Młodych” (The World of Youth)[1] magazine. That’s where he published his first comic, Ten piekielny Barnaba (That Devilish Barnaba), drawn from a script by Jerzy Dąbrowski. He scripted his own comics after that. The comics he created for magazines such as “Razem” (Together) or “Relax” were later published in album form to enormous success. His most famous comics are Skąd się bierze woda sodowa i nie tylko (Where Does Sparkling Water Come from and Much Else), Na co dybie w wielorybie czubek nosa Eskimosa (What’s the Tip of an Eskimo’s Nose Looking for in a Whale?), Antresolka profesorka Nerwosolka (Professor Nervosol’s Entresol), and Podróż smokiem Diplodokiem (A Journey on the Dragon Diplodocus).

I was supposed to talk to the grandmaster of Polish comedy comics deep in the woodland, in his studio full of new paintings. Baranowski isn’t just a classic of the comics medium, but a prolific contemporary painter, as well as a great storyteller and a fount of knowledge about the development of Polish comics, particularly in the communist era.

I was excited at the prospect, but my plans were dashed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Traveling has been rendered difficult or impossible, and face-to-face contact with another person carries a risk of unwittingly spreading the infection to them. We decided to conduct our interview over Skype, so as not to endanger Baranowski.

What was your gateway into comics?

I was born towards the end of World War 2. My father was a sculptor. As a result, I was exposed to the world of art (painting, sculpture, architecture) from a very early age, primarily through books from my father’s library. But comic book art was unknown to me. Comic books didn’t exist in Poland back then. According to the communists, they were a symbol of evil, an example of degenerate American art, a vehicle of American imperialism. That was towards the end of Stalin’s life, when manifestations of imperialism were cracked down on, and the dominant trend in art was socialist realism, modeled on the art of the USSR.

It was only in 1956, a few years after Stalin’s death, that Polish communists relaxed the numerous regulations pertaining, among other things, to comics. That was when I first saw a few black and white strips published on the last pages of local newspapers.

I remember being enchanted by those “stories with balloons” and like every kid I would cut them out, paste them into a notebook. Sometimes I’d color them with crayons. Soon after that there came Przygoda (Adventure), the first comic book magazine in post-war Poland, as well as full-page stories in various weekly magazines. But after two years comics were once again deemed an example of the West’s moral rot and so Adventure, as well as comics more generally, ceased to be published.

Strangely enough, throughout all this time, comics continued to be published in a small scouting publication called The World of Youth.

Can you describe what The World of Youth was and how you ended up working for it?

It was a scouting magazine for teenagers, primarily an organ of PZPR[2]. Comics were the main source of its popularity, but they were used for propaganda purposes, so maybe that’s why they were tolerated. Thanks to comics the magazine lasted throughout the difficult years and closed down only in 1993, after the free market came to Poland, bringing in numerous never before-published comics that killed off the meagre local competition. Young readers in Poland threw themselves at the unknown comic stories that until that point had been out of their reach. The magazine ceased publication, but it retains a cult following, the memory of it returns in numerous publications written by its fans.

In 1973 there was an undertaking to start publishing the magazine in color, on better-quality paper – I was asked to design a new layout and that’s how my adventure drawing comic strips started. At the time I was fresh off graduating from the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, I had a few individual exhibitions, but the editorial board of The World of Youth knew about my previous interest in comics and so they asked me to come onboard and to draw my first comic.

You knew Grzegorz Rosiński as a student. There was also a point when the two of you competed to create for the Francophone market. How would you describe your relationship with the creator of Thorgal?

Rosiński and I were friends back when he still lived in Poland. Of course we bonded over comics. It is not true, however, that I was competing with him in the francophone market. He’d already risen to a certain position and his professional opportunities were considerably different. He’d been drawing Thorgal while still in Poland, collaborating with the renowned Belgian script writer Jean Van Hamme. The introduction of the martial law in Poland in 1981 and the resulting difficulties in professional contacts forced Rosiński to emigrate and settle abroad.

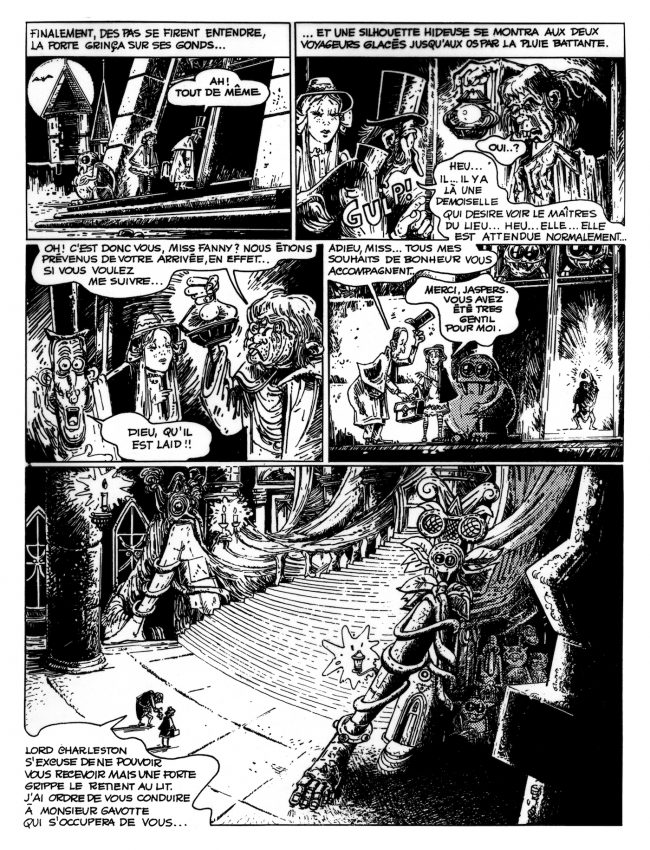

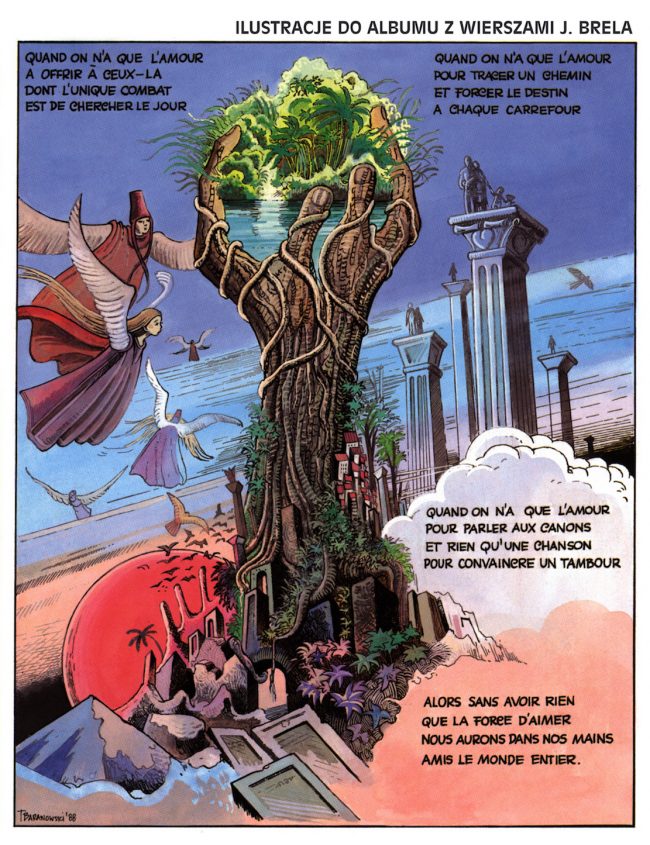

I came to Brussels on his invitation, but the goal of the visit was coloring his drawings for Thorgal and Yans. And that’s what I did to start with: I colored a number of drawings for him. Owing to chance, I showed a few of my humorous comic strips to the editors at the Tintin magazine and the next day I unexpectedly received an offer to work for them. Rosiński said in that case I should go my own way. For some time he was providing an enormous help in that.

Rosiński and I are two completely different sorts of artists. He’s one of the best realist artists in the world, but his work was always dependent on a script provided by a writer.

I’m not as good a craftsman as Rosiński. But I was always my own man. An author of abstract scripts and drawings who had trouble bending to someone else’s vision. Which later on led to difficulties in working with publishers, both foreign and domestic.

What was it like working in Belgium back then? What was the mentality like?

I wouldn’t want to try to characterize the mentality of the Belgian consumer. I was a newcomer from the East and I was grateful for my initial warm welcome to the closed-off, hermetic world of the European comics’ capital. I found myself in it by chance and at the time everyone envied me. I was in the company of renowned and respected European comics creators and that should have been its own reward. I think maybe I wasn’t determined enough in going after my goals. I was also interested in other artistic media and it’s probably my own fault that things turned out the way they did.

You worked in Belgium for two years, from 1984 to 1986, drawing for Jean Dufaux among others. What was the cause of your failure to establish yourself in that market?

The abstract language of my stories made them difficult to translate into French. The scripts for the comics published in Tintin on the other hand were fairly simple and naïve. It wasn’t hard to grasp the concept behind them. They were just “BOOM! POW!” stories. My scripts required more engagement from the reader.

I had an excellent translator for a while, a lecturer at the Institut français in Warsaw, and he was doing an excellent job. The scripts were accepted with no notes by the editors at Tintin. But when he had to drop out due to professional reasons, I couldn’t find anyone to replace him. And then a very nice man by the name of Jean Dufaux visited Rosiński in Belgium. He was starting out as a script writer and he approached me about a collaboration. The problem was that his scripts required realistic drawings. For a while, I tried to bend myself to that style and with time maybe I would have developed more skill for it – but I was unhappy to be working against myself. So I continued to look for another writer in that market and I started to work with an excellent young writer by the name of Michael Bom. He understood me and I was enjoying his funny ideas. In the meantime, I drew a humorous episode about Thorgal for Tintin utilizing or, to be completely honest, faithfully copying, Rosiński’s drawings. Tintin’s then editor-in-chief thought it meant I excelled at realistic drawing, he didn’t understand that it was a mere pastiche. He offered me work, wanting me to continue a realistic series of albums based on his scripts. I refused because I thought it went beyond my level of skill. I think he took it as a personal affront and from that moment on my relationship with the magazine broke down. He started by sabotaging my great working relationship with Michael Bom. I was more and more disillusioned by the unfriendly atmosphere, by the negative reader reviews published with relish by the editor, and I decided to quit this strange relationship. Rosiński meanwhile had less and less time, he was an actual star, so I decided to end things by going back to Poland. For some time Jean Dufaux continued to send me his scripts, but I declined to draw them. I still had a five-year contract with the publisher, but my work, despite being paid for, wasn’t getting published.

Looking at the history of your relationships with editors and publishers (in Belgium or at “Relax”[3]), one could think you have a bit of a chip on your shoulder…

I always held opinion that if someone employs a professional to do something: a plumber, a computer programmer, a doctor, or a comic book artist, that someone should trust the person employed, not try to demonstrate that they know that craft better. But without correcting everything and everyone that someone’s ego isn’t getting stroked enough. Working as an art director in various magazines, I worked with hand-picked artists and I always accepted their work.

If I was being employed to draw a comic for a magazine and someone would tell me how to draw the comic, I resigned immediately. The only ones of my comics to pass the test of time are the ones I wouldn’t let anyone mess with. Yes, there were times when I refused to sign a contract because someone suggested out of the blue that the title of the comic should be changed. Of course, the title could be whatever, but I’d spent many hours coming up with it and there was no point picking at it. That’s still the way I operate, even though I sometimes lose out because of it.

What are the sources of your artistic inspiration?

Everything comes from somewhere. The things that happen around me, my interests, my life experience, everything manifests in my artistic output. I love nature, animals, I’m interested in astronomy, archeology, biology. I used to keep exotic fish and plants. I played jazz on a piano. I have drawn on all of those experiences in making comic book art and painting.

You are a master of panel composition and use of detail in the worlds you depict. I would even say you were a worldbuilder long before that term gained significance in the gaming industry. What’s your approach to creating a world in a comic? How do you start to draw the strange realms you depict?

I always tell painters to get off the beaten track. I construct abstract paintings using my own individual means of expression and it’s the same with comics. I look for interesting layouts that differ from the well-known, traditional ones.

The quirky way I divide one picture into many on one page was surprising at the time and to this day my fans see it as something of a calling card. It doesn’t break any new ground today, but 40 years ago it was a novelty in Polish comics.

In 2012 you wanted to leave comics behind, get back into painting, become a contemporary artist. What were the reasons for this decision?

Having graduated with a degree in painting, I was a so-called up-and-comer. I held a fair number of exhibitions in prestigious galleries. I was praised, I got prizes. But the realities of life forced me to get a job as well. Since I was well-versed in graphic design, I started working for various magazines, designing layouts and typography. I was telling myself that I’m leaving painting behind just for a little while and that I’d go back to it soon. Then came The World of Youth and I started drawing comics. That was going well, so my return to painting got delayed. The delay lasted 45 years. I came back to it after a long time, having to practically learn everything from scratch. I’ve been hard at work for the past 12 years. In that period, I painted about 200 big, expansive, abstract paintings. Some time ago I managed to sell a large painting to a Washington art collector via an American art gallery Saatchi Art. And I’m still painting.

What made you decide to come back with a new comics album after all?

As usual, it was my fans who talked me into drawing another album. They wanted me to draw anything. I was also encouraged by the fact that the re-issues of my previous work are still quite popular. I thought I could try to draw something in the breaks from painting. It took a long time, but the album is almost ready. The publisher is waiting, but I still have a few things to tinker with and I’m in no rush. It’s a children’s comic. A simple story, third in a series, about tiny people living in the grass and tree hollows.

Can you say something more about your relationship with fans? Your work seems to have a steady cult following.

I have a sizeable group of fans and friends who supported me when times were tough. Whenever I’d take a break from drawing comics, they would try to talk me into coming back. They were long breaks, but every once in a while I would start everything over once again. There was also a long period of silence from the publishers. I thought it meant nobody was interested in me or my work. The publishers switched focus completely to buying cheap licenses from all over the world and a freelancer like me was no longer attractive to them. But five years ago a young man[4] approached me about re-issuing my very first album from 1979. I didn’t quite believe it would come together and he’d be successful. But unexpectedly there’s been a renewed interest in my works. In the last five years, 40,000 copies of my albums have been sold and there’s still a demand for them. My old comics pages have recently been exhibited in Paris.

What people seem to particularly enjoy about your work is your puns and wordplay.

A lot of the lines from my comics have entered widespread usage among both young and adult readers. There are people writing dissertations on the language of my comics, I’ve seen quotes tattooed on the arms and legs of my readers. I’ve seen bikes covered in stickers featuring my drawings. Recently I’ve also been approached about putting prints of my panels on a custom clothes collection.

Where did that love for the Polish language come from? Are you a big reader? A linguistic patriot?

I come from a generation that didn’t know internet or smartphones. We didn’t learn things from Google, but from reading books. I had great teachers of Polish at school. My generation, having been imprisoned within a totalitarian system, created its own language to bypass the barriers that the system has put up. I think that the use of subtext in various everyday situations back then influenced the way I wrote and looked at the absurdity of the world.

I take it that absurdity is great fodder for your humor, as it was for Stanisław Bareja?[5]

The Polish absurdity never ends, it comes back again and again, as if in a time machine. I see that in my comics. I take out a story created 40 years ago and it fits the contemporary context like a glove.

As an artist, how would you describe the Polish nature?

I am unable to answer that question. The world has changed enormously and we have changed as a nation. Not necessarily for the better. Populism and demagogy have come into our life and I am deeply disappointed by that. I did not expect something like this to happen at this stage of my life. I always felt a free man and now I feel my freedom is under threat. I don’t know what the Polish nature is right now.

What does humor mean to you?

I enjoy every kind of humor, from simple entertainment to the one that nourishes you when life gets difficult, but as I age and observe the world around me I feel less and less like laughing. I heard that people with depressive tendencies, like me, have a big sense of humor. I try not to take myself or what I do too seriously and so looking back at my past self I tend to have a good laugh.

Your final album is also a humorous story. Do you find it more difficult to write comedy right now, when comedy can provoke a vocal outrage much more easily?

It’s very easy to write a funny political comic because politicians are frequently funny and grotesque characters in and of themselves. That’s why one of my political comics features two vampires. Their dialogues are frequently direct lifts from politics. But I never paid any mind to who’s going to be offended or to the so-called “political correctness”. Of course, in a police state there are special forces in charge of finding elements that make fun of the state or its head. Insecure, small men always get angry when they’re criticized. But the censors themselves tend to be stupid enough not to understand abstract storylines. Or they are so suspicious, they see a critique of the system where there is none. The vindictiveness of a politician with an inferiority complex can result in the artist getting blacklisted from the art world. Which is something I experienced.

How would you describe the life of an artist in Poland right now? Particularly a comic book artist?

I think nowadays it’s similar to the situation of artists everywhere. Unless someone achieves great fame and success while they are still alive, but those are exceptions. If you want to be a comic book artist, you need to devote your whole life to it, regardless of how successful you become. A handful of the best and most enterprising Polish artists work for international publishers. You could say they made it, though I don’t know whether their success was financial as well. But they make a living drawing comics and that’s a success in and of itself. Many artists from my generation are either dead already or they draw comics after hours, because they need to hold down a job in order to make a living. It’s a pity, as they are great artists of the medium.

Do you think comics has a future as a medium?

I think comics will survive and thrive. It’s becoming fashionable. There are people in Poland who have the means to buy original art at auctions, treating it as an investment. Due to its popularity, comics will also be used in propaganda, advertising, textbooks, it will provide a basis for movies. Incidentally, a feature film called Diplodocus[6] is in production, which is based on my comic books.

What are your plans for the future?

I have no particular plans. My work mattered the most to me throughout my life and that’s how it will probably be until the very end. I would like to fulfill my aspirations as a painter.

You mentioned receiving an invitation to New York. Are you going to promote your art internationally?

I have been getting invitations like that recently. I see that my paintings are being recognized, but not in Poland. It would be great to hold an exhibition in Manhattan. But being an artist is currently the province of the wealthy, which I am not, and neither are most of the artists in Poland.

[1] Note on titles: for ease of reading, the original Polish titles of albums and magazines are only used the first time a particular publication is mentioned, with an English translation provided in parenthesis. The translation is used throughout the interview.

[2] Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza (The Polish United Workers’ Party) was the communist party ruling Poland as a one-party state from 1948 to 1989.

[3] Relax – a Polish comics magazine published in 1976–1981. Tadeusz Baranowski left the magazine after a change of editor led to increased interference in his work.

[4] Leszek Kaczanowski, owner of the Ongrys publishing house, who started re-issuing Tadeusz Baranowski’s albums in 2015.

[5] Stanisław Bareja – a director of cult Polish comedies satirizing the realities of life In communist Poland. His most famous works are Miś (The Teddy Bear) and Co mi zrobisz jak mnie złapiesz (Catch me if you can).

[6] The movie is spearheaded by comic book artist Wojtek Wawszczyk, who talks about it in an interview with The Comics Journal here.