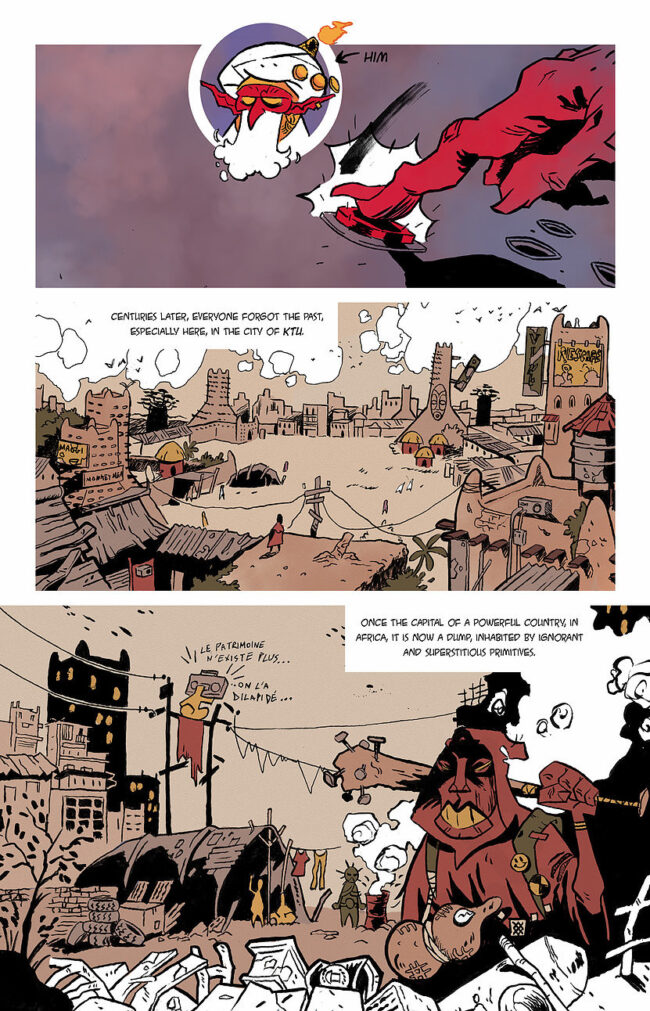

Juni Ba is an illustration and comics artist and writer. I recently came across Ba’s work with the announcement of his forthcoming graphic novel Djeliya from TKO Studios. Djeliya tells the story about Mansour, the surviving prince of a fallen kingdom, and Awa, and his Djeli (royal storyteller) as they set out to find a wizard and the power that he used to destroy the world. During our conversation, Juni and I talked about his artistic influences, tracking comics down as a child in Senegal, and the responsibilities of the storyteller.

Tiffany Babb: You’ve mentioned before in other interviews that you learned a lot about storytelling from the media you’ve consumed in your life. Can you tell me about the artists and art that have influenced you?

Juni Ba: The question is kind of difficult to answer because of the huge amount of stuff. The very obvious ones would be Hellboy, the Gorillaz. Shaman King. I’m picking one from each of three major poles, I guess. But even then, those are the big ones, and you have all the others under from each of those countries. On the French side, it would be Franco-Belgian, it would be Spirou, the biggest inspiration, and then Asterix.

The list is really long, and yes, making the book was also about trying to take what I learned from those things, in terms of how to tell stories and how to draw and then trying to apply to the more African influences that I, as a kid, I didn’t necessarily think of mixing with the more comic-oriented stuff. Then just one day when I was twenty-one, it just clicked. And I thought Yeah that would be cool.

Can you talk more about growing up in Senegal and your introduction to comics there?

I don’t remember the introduction itself, because I was so young. But basically, the thing is that the city I grew up in had one library. It had a fairly limited collection of comics. You had the big French ones, and even then, not all of them. It was kind of sparse. You would have a few copies of a few different series. The manga side of it was literally one of those shelves that turn on themselves?

Uh… yes! Like spinning racks.

Yeah! Like that was literally all I had in terms of manga selection. There was one spinning rack. That was it. So, I had to rely a lot on the internet. That library was really useful to introduce me to certain things, and then I would have to use the internet to go look for more copies or more issues of the certain series.

I would say that the biggest thing was that it sort of forces you to appreciate everything you have, because when you have only one, like, Hellboy volume to read for an entire year before you can go to a European country and buy the rest, you really read the hell out of that book!

The limitations were sort of a blessing in disguise. It forced me to really appreciate and dig into the details of what I really had. And also, it made it all the more precious to have the things that I had because you have to sort of work more to get them. I would walk an hour in the sun some days to go to the library because my grandparents were living an hour away, and I needed one specific comic that I knew was there. I didn’t want to miss my chance to get it, so I would walk there to get it and then come back. I showed way more dedication to comics than I ever did to my school work.

Well, it’s paid off right?

Yeah! Like that’s the one victory I have. I can show my family and my grandparents, especially— the obsessive aspect that I had actually worked into making something tangible.

What language were you reading comics in at the time? French?

Yeah. I learned English when I was… I started using it when I was around eighteen/nineteen because that’s when I started looking more into the American side of comic books. American and British, really. I started becoming way more interested in reading it in the original language because I already had the basics. It was much more interesting to read in the original language. The French translation was often lacking, and you only really realize that when you’ve learned the actual language and you notice all the different nuances that you’re missing.

You really focused on learning English specifically to read comics?

Yeah. And watching movies.

That’s very impressive.

That was the main draw. I think it really started when I got Hellboy and The Avengers movie came out. And I was like, there’s this huge pantheon of comics that I never really looked into. Marvel Comics was sort of a gateway. I don’t really read much of Marvel or superhero comics now. I’m more of an indie person. But I started out that way, and I guess I sort of proved the whole thing Stan Lee was saying about how comics help people learn the language and learn to write and read.

Is there a comics scene in Senegal?

Oh boy. I want to say “not yet” because— I think it’s a bit more complicated than that because the creators exist, but it’s a bit more about having an actual industry. And there isn’t one yet. We don’t have publishers who do comics. We tend to have one small thing being done here and there. I think the first comic book magazine for kids that the country ever had was created last year, and I haven’t yet seen any copies of it, so I don’t know what it looks like and what the quality of the books are yet.

It’s a post-colonial thing. The generation of my grandparents was about “We want to be free.” The generation of my parents was about “Now that we are free, what do we do? What do we build?” And my generation is more “The building has been done, and there’s still a lot of stuff to do. But now that we have sort of steady foundations, how do we grow it into more things?” And naturally comics was not the priority in the age of building things.

There’s something unique about growing up and wanting to do something that no one around you is doing. What was it like wanting to do this thing, that, I’m assuming, some people found a little strange?

The thing is, the cliché of the African parents is often that they are very strict and that they don’t want you to stray too far from very sort of useful careers, I guess. The very cliché thing is that they want you to be a doctor or an engineer or a lawyer or stuff like that. Or at least something that would be steady.

My granddad was that kind of person when he was younger. He made my parents, my dad, go through quite a lot of trouble in terms of living up to the expectation. But my dad and his brothers grew up with comic books, French and American ones. I learned that my aunt used to read Thor and The Silver Surfer. Which blew my mind! The fact that it was the sixties at the time, sixties or seventies, and she was reading that when she was a kid.

So basically, that generation grew up reading comics and were told by their parents that it was a stupid thing to do— that it would bring nothing. And then I show up, and apparently, I contributed to sort of forcing my grandfather to have a change of opinion. Because he mellowed out over years, and when I was eleven, some family friend came up to him and said “I saw your grandson drawing in the backyard. He’s really good. He should try to make something out of it.” And my grandfather was actually agreeing with it! Something he would never have said about his kids.

So, I was lucky, and I think the biggest thing for me was that my dad always said, “You can do anything you want as long as you work at it and don’t slack off.” He never understood the stuff I was into. All the fantasy and science fiction. That was really way too weird for him. But he would still take me to see movies and buy the comics I wanted. And he encouraged me to do this stuff even if he didn’t get it. He financed my art school, and so I had very strong support from my family. While at the same time, they would often even get mad at me for being a child who is way too into that stuff to the point when he forgets reality and gets too obsessive. They would tend to bring me back to reality.

Djeliya is a bit of a reaction to that. It’s a book of fantasy, but it's really based on me observing the world around me and actually making a story out of it. Sort of a, “Yes, I was watching Cartoon Network and talking about weird robots, but at the same time I was listening about what you were saying about current politics or something.”

Can you tell me about what it was like when you started making comics for an audience?

Oh boy, Anxiety. The weird thing is that I never really approached it as thinking about it in terms of making it for an audience. Mostly because when I was in my last year of art school, I decided to make comics based on West African folklore. I wanted to do it simply because that was what I was interested in, and I was even told to give it up because there was doubt among the teachers that there would be interest for this. And I kept doing it because I felt like I needed it for me.

When I left school and put it on the internet, I started getting traction from those [comics], and that’s sort of how I got enough attention that I could have approached TKO with this project. Even when I signed with TKO, they said the word “YA” for the first time, and I was like “Oh yeah, sorry. I was supposed to figure out an audience for the book.”

When you first started putting comics online, that was through Kugali, right? Can you talk about how that all began?

Yes! I think the biggest thing for most African creators is that without the Internet we would not be able to do what we do, either because of the lack of infrastructure in the countries themselves, or in my case, going to Europe to study, the lack of support there because they don’t really understand what its about and they have no interest in it. So, I went to the internet, and I started looking for likeminded people, and I found Kugali on a Facebook page [laughs]. We made one fanzine and then a second one, and you know, it just started snowballing from there. Now I’m making my own comics and they have a TV show with Disney. Yeah. I like to go back to my school and telling my teachers about how its going now and how wrong they were.

So much of Djeliya revolves around the stories that are told to us and subsequently the stories that we tell. As a storyteller yourself, what do you think are the main responsibilities of the storyteller?

Yeah. I’m going to use an example, a realized example. I guess, a big one that could be observed is the case of the propaganda movies by the Nazis, and the same principle applies even now, today. Every government uses propaganda in some form or another. It’s just that the Nazi are a very evident and easy-to-use example, because the aesthetic they created was effective—so effective that then, decades later, George Lucas decided he’s going to use that for his Empire. I sort of wish I could talk to the people who made those propaganda movies and posters, in terms of just being able to ask them what do they think was their responsibility there? And do they regret anything?

I often think back to Dave Chappelle who famously refused a big contract because he didn’t want to work on his TV show anymore. The reason why was he mentioned how he saw someone laughing about black subjects in a way that was— it was not a laughter from someone who understands it. It was the laughter from someone who has prejudices and sort of got them reaffirmed in a way. And he said, I’m going to paraphrase, but I think he said something about wanting to be responsible with the stuff that he does. I feel like that’s a pretty good way to approach it.

I think the base responsibility of the storyteller is—tell the stories you want to tell that are truthful to you and everything, but try to be responsible about it. Especially when your stories serve a political or social purpose.

It always bothers me a little when I watch a biopic and certain changes were made. It tends to be very carefully chosen elements like a movie about racism in the US in the sixties, and they invent a completely fictional white person who is super nice. It is a calculated choice. It’s not just any change. It’s on purpose, and the person who did this, I feel like, sort of did wrong with their responsibility.

Right. They’re falsifying things to make them more palatable to white audiences.

Exactly. It is a form of lying that I don’t think is really doing much good. Because there is a form of manipulation that is more about soothing the person watching, which they shouldn’t be doing. Not with a subject like that, I guess.

Speaking of truths and social truths, you included a bibliography at the back of your book. Can you tell me about your process of researching for Djeliya?

Most of it was research done for myself. I had an inkling of the content of everything I researched, because you hear about those stories when you are a child. Especially the very big epics that created the identity of an entire nation. Of course, you’re going to hear about that. But I never actually read the stuff, so what I did, at first, was simply going to my grandfather and asking, “Could you give me books with folktales in them?” From then, I started taking notes on the kinds of tropes in them, the different nations that it mentioned, and I started looking into the history of what actually happened compared to the stories told and stuff like that.

A lot of it was a sort of a self-discovery type of thing. It was half historical research and half anthropology, just to try and figure out what was it like, essentially for my ancestors, I guess. I mean, learning about my own history and the customs of my people, and I learned a lot of things that recontextualized elements of my everyday life as a child. You see people do certain things or talk a certain way, or you hear about like them referring to certain events, and you don’t necessarily know what it’s about, but then you read a book about it, and you have an entirely new context about why things were the way they were.

Then you have to turn this into fantasy, so it’s more about trying to figure out what the point of it is for you. Like this historical event—what sort of lesson do you think you could take from this? And then trying to apply to a story that serves—like the folktales that I started my research with, how do you distill that into a story where a person regardless of their age, or background really, is going to be able to understand what the message is?

Your work, and it feels present in Djeliya, but now I’m thinking about Monkey Meat as well, seems to share a lot of structure and imagery from video games. Video games have— not a less structured narrative, but a less controlled narrative. But you seem to use that structure to open up your story to include the reader. Can you talk more about the effect that invoking video game-like imagery has on your stories?

I don’t even do it on purpose. Because, truth is, I haven’t been an avid player of video games in a good ten years. I play games here and there now, but when I was a teenager, I would play a lot of them. Something that I found very impressive in video games was how simple the narrative structure would be. Because very often it’s about giving you a sort of context or status quo and then launching you into whatever mission you have to accomplish. Especially older types of video games or platformers and stuff like that. I found it really useful because, when I have to make a story, I sort of want to streamline it as much as I can. Because I have, one of my biggest weaknesses is the tendency to want to put a lot of things, and I have to rein myself in and remind myself that you have to streamline it to bare essentials.

I often use Sonic the Hedgehog as an example, because in design and concept originally at least, Sonic was perfect in terms of simplicity. He was visually very simple. Very striking and easy to remember and stood out from his background. And in terms of concept, it was literally just—there’s a mad scientist who kidnaps animals, you have to run catch him and stop him every time. That was it. It was very simple and very effective.

The structure of Djeliya is a bit like “every step is a checkpoint,” almost. Every time they save, at the end of the story or a new step in the tower, they have learned something and they can move onto the next step. But yeah, I hadn’t actually made the link with the video game aspect of things, but yeah. Indeed.

It is interesting. I think, especially considering the ending of Djeliya. It’s kind of an open ending, right? It’s an ending that has, not necessarily a choice for the reader, but the protagonists have finished making their decisions, and there’s still a decision to be made. Now it’s just out there. That seems like a video game thing as well.

Yeah. I tried to engage. I was really struggling to think of an ending for this. Because you want to come up with something that is satisfying, but at the same time, you don’t want to push your characters in a direction where it wouldn’t make sense for them to go. And the solution that I ended up finding was in folk tales actually. Because, the very basis of the folk tales initially was to be told to an actual audience in front of you as you’re telling it. So, it gave me this incentive to be way more… almost meta in terms of doing something where the reader themselves is being asked to actually think and engage with it. Even if it’s a book, and you’re not actually talking with someone, you still have to come away from it with— I don’t want to say a job to do, because that sounds like a chore. But you have your own self to put into it as well.

So yeah, the video game thing wasn’t necessarily the goal. It was more of an old folk tale thing, but now actually, I think we made the connection between old folk tales and video games in terms of actively engaging your audience!

You’ve spoken before today about having difficulty talking to publishers and instructors who aren’t sure what to do with your work. How you would like your work to be seen, by publishers and by readers

I have seen a lot of different words thrown like “Afrofuturism” and stuff like that, and I don’t subscribe to it, mostly because that was not even a concept I had when I started working on this. I even discovered the concept of Afrofuturism after writing maybe half the book. I was just making fantasy, basically.

And a pet peeve that I tend to have is that we tend to want to put things from outside of the usual European influences into boxes based on where they come from or what subject is easily marketable. I just want people to look at it as fantasy. If it falls into a subgenre of something, sure. No problem there. But even the use of Afrofuturism— Afrofuturism itself is such an American thing about African American issues and subjects, and I am not an African American. And I am not trying to speak for them or anything like that.

This is fantasy from an African perspective, and it can speak to absolutely anyone anywhere. Just like I am a kid from Senegal who loved Narnia and felt represented in it because I felt the characters and felt them close on a human level. I figure that a kid from Taiwan or Texas is going to have the same reaction to my characters, and I don’t need a specific label. It is fantasy, just like Narnia is.

Djeliya is about legacy and how we live up to it. With this book, you’re also continuing a legacy of storytellers shaping and adapting these folklores and oral histories. Do you feel like you’re part of the legacy shaping the folklore or do you feel like your work is a separate thing?

The thing is, I feel more like I made a work of absolute fiction based on real life things, sort of? I feel like I made a gateway, I guess. It’s sort of like how my relationship with Japanese culture was— a huge interest in it as a teenager because I was reading manga, and you want to be a creator when you grow up so you look into how it was made, and you start realizing that everything in Naruto was actually taken from Japanese folklore. And you’re like— oh, it’s that easy! Then you dive into page after page of Wikipedia articles about Japanese creatures that inspired the book.

That’s sort of what I want the book to be like. I want people to read it and have fun and be like, “I want to know where it comes from.” The backmatter of the book is for that. I want them to read about it, to realize it has an actual origin in real life and have certain keywords that they can use to do their own research if they’re interested, and then read the books and watch the movies. I feel like I work, not so much as an expansion of the folklore, but more as, sort of, an invitation to it.