Joe McCulloch's got the Week in Comics covered again this morning, along with a short essay on an obscure example of bande desinée.

Laura Hudson interviews Achewood creator Chris Onstaad about his recent return to webcomics. In it, Onstaad talks a bit about Jim Woodring:

Jim Woodring is great, and is one of those people who will honestly admit to you that, "Yeah, my brain's a little f**ked up." His comics are sort of a manifestation of his brain. It works for him. He's a really wonderful guy. He has this big three-story place with big, gothic abbey rope hanging in front of the front door. The rope rings a little bell to let you know that someone's at the door. One time it rings in the foyer so his wife opens the door, and there's this little cat there that came in from the road. So they let the cat in, shut the door, and we all go about our night. Then we watched Popeye for two hours. That's Jim.

Chris Mautner puts together a solid list of six books from 2011 that deserved more attention.

The A.V. Club has their own list of fifteen comic strips that were adapted into "forgotten" television shows. Not all of them are equally forgotten, though. The Far Side, I'll grant you, but Garfield?

Robert Boyd doesn't seem to write much about comics these days, but I check in to his blog now and again all the same just to make sure he hasn't tried to slip something through unnoticed. Last week, he pulled out an excerpt from the late short-story writer Donald Barthelme talking about conceptual art:

BARTHELME: Conceptual art isn't something I'm overly fond of. It seems to me entirely too easy...

RUAS: Why would you say it's easy?

BARTHELME: Well, because it is easy.

RUAS: To be able to delineate concepts and have people understand the concept?

BARTHELME: Yes. I think as art it is entirely too easy. [...] Had I decided to go into the conceptual-art business I could turn out railroad cars full of that stuff every day.

There's a bit more at the link. I'm not personally acquainted with how easy it is to turn out conceptual art, but knowing Barthelme's work, I tend to believe his claim about his own facility for it. (I assume it goes without saying that people tend to devalue whatever comes naturally to them.)

For some reason (perhaps because of Barthelme's frequent pseudo-comics use of extensive illustrations?), this reminded me of my long-time privately held theory that conceptual artists do more or less the same kind of thing that gag cartoonists do, only without using paper and ink, and without necessarily going for laughs—though a fair amount of conceptual art doesn't attempt much more than that. The title or artist's statement is frequently used as something equivalent to a cartoon's caption. Light amusement to refresh the tired gallery-goer, I guess. This is not a comparison meant to reflect poorly on either genre; there are at least as many bad gag cartoons as there are bad conceptual art pieces. (And of course, not even gag cartoons are always meant to be humorous, as witness Abner Dean.)

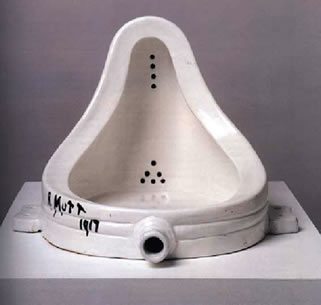

Marcel Duchamp, who is of course usually credited with starting the whole conceptualism business off, began his career as a gag cartoonist submitting panels to Parisian literary journals (have his cartoons ever been collected into a book? I'd love to read them), and comics historian M. Thomas Inge has suggested that the "R. Mutt" signature Duchamp scrawled at the bottom of his most famous "readymade" was an explicit reference to Bud Fisher's A. Mutt from Mutt and Jeff.

Marcel Duchamp, who is of course usually credited with starting the whole conceptualism business off, began his career as a gag cartoonist submitting panels to Parisian literary journals (have his cartoons ever been collected into a book? I'd love to read them), and comics historian M. Thomas Inge has suggested that the "R. Mutt" signature Duchamp scrawled at the bottom of his most famous "readymade" was an explicit reference to Bud Fisher's A. Mutt from Mutt and Jeff.

This connection between gag cartooning and conceptual art seems too obvious to be genuinely original to me, and I assume I must have gotten it from some now forgotten source. So I poked around online seeing if I could find anyone else saying the same thing, and the best thing I could come up with was a 2009 New York Times op-ed by Dennis Dutton that I'm pretty certain I'd never seen before. In it, Dutton says:

The appreciation of contemporary conceptual art, on the other hand, depends not on immediately recognizable skill, but on how the work is situated in today’s intellectual zeitgeist. That’s why looking through the history of conceptual art after Duchamp reminds me of paging through old New Yorker cartoons. Jokes about Cadillac tailfins and early fax machines were once amusing, and the same can be said of conceptual works like Piero Manzoni’s 1962 declaration that Earth was his art work, Joseph Kosuth’s 1965 “One and Three Chairs” (a chair, a photo of the chair and a definition of “chair”) or Mr. Hirst’s medicine cabinets. Future generations, no longer engaged by our art “concepts” and unable to divine any special skill or emotional expression in the work, may lose interest in it as a medium for financial speculation and relegate it to the realm of historical curiosity.

This is another interesting point of comparison, but as Dutton's implicit admission that at least Duchamp's work hasn't dated too much makes clear, some concepts are sturdier than others. And of course many New Yorker cartoon gags are as funny now as they've ever been.

But not necessarily the best gag cartoons. Cartoons, like many pieces of conceptual art, are meant to be ephemeral—amusement or provocation for a particular cultural moment. There's nothing wrong with that—amusement and provocation are as necessary now as they will be in the future. But because of that ephemeral nature, there is usually something small-seeming and limited about them. In that sense, even Jeff Koons' forty-three-foot sculpture of a puppy is a miniature.