Matthew Thurber grew up on an island, was a teen when grunge broke in the Pacific Northwest and eventually made the trek across the country to attend art school at Cooper Union in New York. He never left the area, and now resides in Brooklyn with his girlfriend, the artist Rebecca Bird. Thurber is known as a multimedia artist. In addition to the recent publication of his collected masterpiece 1-800-MICE (published by PictureBox), Thurber has also just released a new album, under the name of his one-man musical project, Ambergris. Thurber is a veteran of the indie music scene after his stint in Soiled Mattress and the Springs.

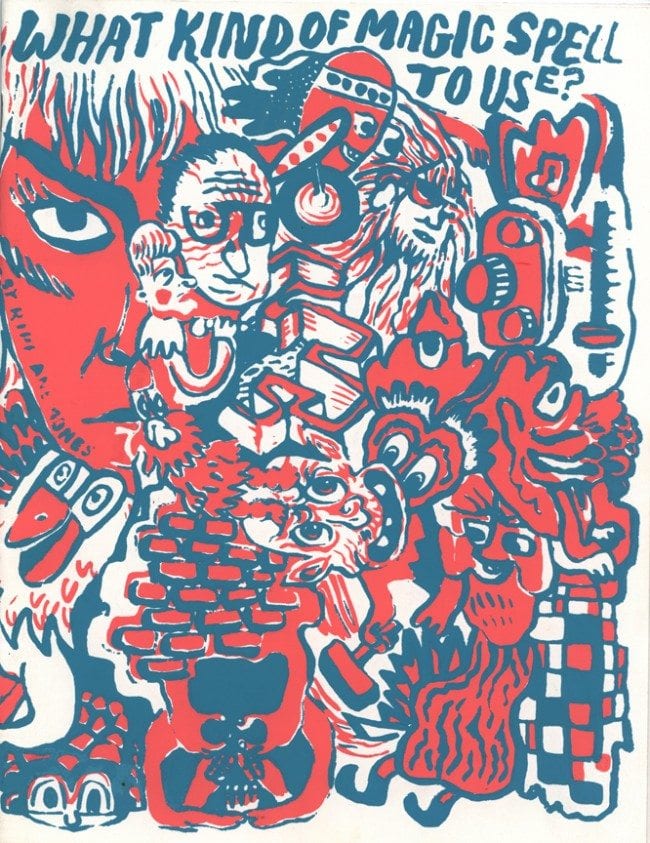

As a cartoonist, Thurber's work reveals a tension between complex but traditional narrative structures, boldly avant-garde visual storytelling, and the overall sensibilities of a gag cartoonist. 1-800-MICE is the culmination of many years of exploration in comics and is hilarious, absurd, thought-provoking, compelling, and pointedly satirical all at once. It's a sprawling epic that leaps between the narratives of a number of different characters before drawing them together in unusual ways, depicting life in a vibrant, tense Volcano City set in a fantasy world where trees are sentient, banjo-playing gangsters hire sushi-chef assassins, and both consciousness and identity are highly fluid concepts. In this interview, we discussed Thurber's development as an artist in a number of different fields, his diverse range of interests, and the wide variety of themes that emerge in 1-800-MICE. He was an engaged (and engaging) interview subject willing to explore any idea I introduced in great depth, and did so with a warm and open sense of humor.

On the Island

TCJ: You're from Lummi Island, Washington. What was growing up there like? What was the size of the community?

Matthew Thurber: Lummi Island was beautiful and small. The phone book was one page long, double-sided. No police, so famous as a place to party. Also lots of mushrooms and newts. Fishing shacks moldering in the woods. A commercial fishing industry kind of limping along/dying. Indian reservation on the other side of the water. A safe, dreamy atmosphere and somewhat claustrophobic at a certain point.

TCJ: So just a few hundred people live there?

MT: There’s probably like 500 people year round and then it goes up to like a couple hundred more in the summer-time.

TCJ: How did your parents come to live there, and where were you born?

MT: I was born in Mt. Vernon, Washington, and then I grew up in Bellingham, which is a college town. It’s close to Canada, it’s up in the very northwestern corner of the state. and then my uncle had lived on the island, and we eventually moved out there when I was six. I think partially so me and my sister could go to the grade school there, which was a good little one-room school house. It was actually a two-room school house. They had one room for the young and first- through third-graders and one room for the fourth- through sixth-graders. It was a pretty unique place to grow up, for sure. I don’t know what I can say about it.

TCJ: You said that at a certain point it got claustrophobic. How old were you when that started to happen?

MT: When I was in high school, I was spending a lot of time off the island and becoming enticed by what was available in Bellingham and the college town, and also trying to go down to Seattle. I mean, I love all the people on the island, you know, but it’s just like there was the promise of so much more, and that promise was shown to me by my parents and by my teachers. I did some summer-school classes farther away, and met kids there. These were kind of these optional nerdy summer-school classes. It wasn’t that I necessarily ... well, maybe I was dying to escape, I don't know. I love it there, but at the time when I was 18, I wanted to see what else was [out there].

TCJ: Are your parents still there?

MT: Yep, my mom works at the school, and my dad works on the ferryboat. It’s a really lovable place, it’s a pretty special community, but you know it’s the kind of place where you know everybody, for better or for worse. Some of my pals are still there, so it’s really nice to go back and visit.

TCJ: What do your parents think of your career now?

MT: Oh, they're really proud of me and really, really supportive. They're wonderful people, I really love them. They're really happy the book came out and have been really supportive the whole time.

TCJ: Do they read all your stuff?

MT: They don't read all of it, but I try to send them stuff, and they're on Facebook so they see announcements.

TCJ: What did they think of 1-800-MICE? There's some pretty wacky stuff in there.

MT: I don't know, [but] my dad's favorite movie is A Boy And His Dog.

TCJ: (laughs) Okay! Never mind!

MT: They're not going to be that appalled. I was always worried at first that I thought it was going to be a big deal, but it was only a big deal in my mind, drawing sexual stuff. I think when I was 13 and drawing lots of grinning, malevolent looking guys holding butcher knives. They were a little worried then, but then they got over it.

TCJ: So they've always been supportive of your career as an artist? They haven't tried to compel you to have a back-up thing?

MT: This was always the only thing that I was going to have. There wasn't going to be any Plan B. They told me they'd be happy with whatever I did, even if it was driving a truck.

Growing Up With Comics

TCJ: Were comics a part of your life growing up? What comics did you read?

MT: Yes, they were available at the local store, The Islander, and within budget so I bought some there. I and my friends were pretty worked up about Bloom County and used to imitate Bill the Cat saying "Ack" jumping into the air. Later, I entered a dark phase of Elfquest and then Sandman/Batman romanticism. I was really into the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles when I was 12 or 13. I was just being blown away by what you could do, coming from Todd MacFarlane's Spider-Man or Wolverine and then seeing Frank Miller's Dark Knight and the more avant-garde Batman works being created, [like] The Killing Joke, etc. It just seems like expansion all the time: "This is cool, this is cool." Finding out about underground stuff. When I got into high school, I became more of an arty snob. Superheroes wouldn't have done it for me at that point. I wanted to see Blue Velvet and Gus Van Sant movies and Rocky Horror, but then I found RAW at that point. I was a total aesthetic asshole [Clough laughs]. I remember making fun of comics by the time I was in high school. I guess that was my period when I was like ... I didn't reject it, I just got interested in other stuff. I still liked the other stuff.

TCJ: Did you read any Fantagraphics stuff at that time? Did you read Hate when it came out?

MT: No, I didn't read Hate. I didn't pick up on that stuff until I was 17, 18. I got really into zines and art.

TCJ: What kind of zines?

MT: Murder Can Be Fun, Answer Me by Jim Goad, various kind of zines coming out of Olympia, Cometbus. There were a few good zinesters in Bellingham.

TCJ: Did your parents encourage reading comics? Did they give them to you?

MT: Yes, definitely. My mom was always taking us to the bookstore and enabling and nurturing a sweet tooth, or a book worm tooth, a sweet book worm tooth. Mom xeroxed my first comic book for me. They let me be a nerd because I convinced them I could be a writer someday and they could give me stuff and it would be all channeled into my becoming the next Stephen King...the joke was on them!

TCJ: Did you have friends or family who read comics?

MT: Not really family, though my adult cousin in Vegas once revealed a stash of D&D paraphernalia which blew my mind that adults could still be into that stuff. My sisters were not nerds, they liked Archie. My friends on Lummi Island were into various interesting things: making comedy videos, World War II, D&D and figurines, Warhammer, Monty Python, etc., etc. A lot of lore was passed down from Noel Dickinson, who was kind of like a mysterious New Wave dark knight, in high school while I was in sixth grade or so. I found him intimidatingly cool: he dyed his hair and wore a trench coat. And the Satanists were rumored to be out to get him, to beat him up. The lore of interesting culture, Depeche Mode and whatnot, descended from Noel to the Phillips brothers and then to me.

TCJ: How old were you when you started drawing? Did you have friends or siblings who drew with you, or was it strictly a solitary activity? Were you encouraged in this pursuit by your parents?

MT: I drew with pals in school. I drew and wrote all the time, it was encouraged. I am the product of a nurturing mushroom environment.

TCJ: As a multimedia artist, have you always had that desire to dabble in a number of different arts? Were you always doing music and making movies/animations?

MT: Yes, probably because there were other people to make stuff with. The Phillips brothers and I used to make videos, which we called "skits." My nickname was "Bob" in grade school and we made some parodies of the "Man From Del Monte" commercials called "The Bob from Del Monte" in which I would be inspecting some tomatoes and then someone would whip out a pistol and the rest was a chase scene. Later, with my friend Raven and others, there was a good cartooning/creative writing/music posse in high school. Tom was doing a public access show a bit later. We did lots of recording on four-track. Rap songs, parodies ... Tom and I had a band called "Durchschnit Atomkraft" that played only once, at a basement show. We used to do jam comics in Sherrie's, a 24-hour restaurant. I got into more "experimental" or pretentious drawing-writing-cartooning-collage stuff in early high school. Making zines, etc. What I made with my friends was more like comedy and entertainment and for fun.

TCJ: Given your current wide range of interests, what sort of cultural influences have had the biggest impact on you, both as a consumer and performer?

MT: Well, my dad is a musician, so seeing him play fiddle all the time when I was a kid and hanging out with jam sessions in our living room [was an influence]. I think maybe reading about Dadaism in the library ... reading about, then hearing and then seeing Sun City Girls and Boredoms in high school ... being kind of isolated and listening to a lot of radio throughout growing up, and reading about stuff in newspapers and zines but not really experiencing it ... living near Bellingham, which had some amazing bands in the '90s like Noggin and The Reeks and The Wrecks ... reading about films like Eraserhead and then finally seeing them ... seeing the Crumb movie with my uncle when it came out.

Schooling

TCJ: A very basic question: what year were you born?

MT: I was born in 77, I’m 33.

TCJ: That’s very interesting, that would put you at about 13-14 years old when grunge really hit the Pacific Northwest. And you were in high school, basically, or junior high school—was that something you became immediately aware of?

MT: Oh yeah, totally. Just prior to that, I mean, there was kind of a festering trash rock scene that came out of punk and stuff, and I was becoming aware of that, and had gone to a few shows in people’s garages or basements. Then in high school, the first day of high school, you know, I remember sitting on this blanket outside of school or sitting on the grass, and people were smoking and also blowing bubbles from one of those little bubble wands. Just like a little congregation of geeky hippy or punk kids and somebody was like, “Hey dude, you should listen to Nirvana!” and threw a cassette tape of Nirvana down on the blanket, and that was the first day of school. It was like a silly, cliched event or something.

TCJ: Wow, that’s kind of insane.

MT: I know, yeah, and I never got to see Nirvana, but I saw a ton of other bands at that time, Bellingham was a good stop of the circuit, you know, it was a college town [Western Washington University] and it had a great music and arts space called the Show-Off Gallery, that was basically like a loft space, you know? Some people lived there and they threw amazing shows all the time, and there were good bands at the college, too.

TCJ: That’s interesting, you’ve lived these weird narratives, almost the narrative of the boy growing up on the island, and then coming into this story of [the] punk-scene, and seeing the exploding thing happening there. When you were going through these experiences, did you process everything as normal, or did you process everything as "This is really interesting, and maybe not everyone else lives like this?"

MT: I think everybody was pretty cynically aware of what was happening in the music scene, and aware of that sort of narrative of Seattle blowing up, which all seemed sort of comical to a lot of us who had a wider range of interests. My own narrative, yeah, sometimes seems a little funny, but I mean a lot of people have a story of coming from a small community, and escaping that, and going to a big city and finding themselves or reinventing themselves or discovering anonymity. Some people’s narratives are that they stay in their communities and contribute to them and become a lifer, or an important part of the arts there. I don’t know why New York. I was excited to go to New York, specifically just because of the kind of art and literature and stuff that I was reading about. When I was wanting to jump in a car and run away in high school I wanted to go to New York.

TCJ: Given where you were raised, what was it like to move to New York City?

MT: It was pretty crazy. I didn't go to Brooklyn my first year. I was terrified the first time I went to Williamsburg! It had a bad reputation still! At least among wussy college students. I've been here for a long time now, since 1996. I used to get really unhappy about it, but I actually think that I would be unhappier in any other smaller town. I used to get jealous of Providence, Baltimore, etc., but then I realized New York is still the best, the most intense, most amazing! I love it. I always need more information. I'm so happy that there's always more to learn here. I'm getting obsessed with reggae and calypso music right now and there are like five stores that sell that kind of stuff that I can go explore! And every day brings a strange new episode, or twenty of them. Today I got my thumb snarled in somebody's iPod cord getting off the train .. .it's actually gotten better and more enjoyable to live here the longer I've stuck it out.

TCJ: What was your experience like as an art student at Cooper Union? Were you still making comics at the time you enrolled? Did they encourage comics there?

MT: I guess they didn't discourage them. I didn't need to do them while I was there. I was reading comics among lots of other things, and doing narrative scroll projects and drawings with words and pictures. Unlike everyone else who is still bitter at their painting teacher, I was able to bypass that over-familiar confrontation and work on videos and animation and drawing and stuff. Now there are cartoon schools where you can just burrow into one medium and never learn to do anything else! It seems a little tunnel-visioned to me. Anyway, I loved school and was extremely glad to get the chance to go.

TCJ: What was the Cooper Union neighborhood like at that time?

MT: Well, it’s right smack dab in the middle of the East Village right next to St. Mark’s Place, so there was a real youth culture, or kind of [a] silly punk culture. There were still a lot of very lively music venues in the East Village. I don’t feel that there are as many anymore. It was kind of like the last couple years of that area as a bohemian center, before it all migrated to Williamsburg, and maybe just because I was young when I moved there, I didn’t go to Brooklyn or Williamsburg for the first whole year that I lived there.

TCJ: You were terrified of the idea of Brooklyn.

MT: I was too caught up in trying to process there being art galleries and the NYU library where I would go and watch movies and just an infinity of cultural opportunities and crazy book stores like the Strand. I mean, I lived upstairs from St. Mark's Bookshop. The Cooper dorm was upstairs from there, and the anthology film archive was several blocks away.

TCJ: Yeah, it’s crazy that you lived upstairs from St. Mark's Bookshop, which is one of the greatest bookshops I’ve ever been in, and it’s actually in danger of being forced out right now.

MT: Yeah, by my school! (Laughs) Because it’s a free school, which is wonderful, but then the way they make their money is by becoming landlords in that area. The rent has been $20,000 a month, they’re petitioning to have it reduced to 15,000, but that’s a crazy situation. Maybe Cooper Union should move to Staten Island or something (laughing). That was exciting and crazy for me, and it still hasn’t felt like it entirely has sunk in, but I’m glad I got to live in Manhattan, at a time when there were more subcultural or weirdo, cheap, poetic elements to the place. It’s not cheap, and if you look at movies, like that Downtown 81 movie, and you see how crazy and vacant it all was, or if you imagine people having loft spaces in SoHo that were actually affordable, that’s the reason that it became like something interesting bubbled up from there. That’s the same reason now there’s more going on in more remote parts of New York, [where] there’s still tons and tons going on, it’s just those loft spaces and spaces where you can have events and printing presses and gallery shows are now far flung and people have to travel pretty far to get to them as opposed to like in the '50s where all the artists lived within twenty blocks of each other.

TCJ: Did you read Kim Deitch’s autobiographical stuff he wrote on the Comics Journal website?

MT: Yeah, I read them all, they’re amazing.

TCJ: They really are, and it was interesting to hear Kim talking about how the Filmore East was here, I lived right next door to it, and the East Village Other was two blocks away from that, etc. Even up through the '80s that was still pretty true, where that the Lower East Side and the East Village were still kind of scuzzy, and there were tons of musicians and artists.

MT: It’s hard to imagine people moving around at that time, because I feel like you’re always having to whiz around like on a subway or bike to get to one thing or another, but at that time did people just move very slowly or did they walk down the street very slowly? [Clough laughs] Were they more sedentary in the '60s in a way?

TCJ: Everything was so localized. I guess everybody walked everywhere, is the first thing I gathered, because you never heard one Kim Deitch subway story.

MT: Yeah, that’s true.

TCJ: [They] just tried to get by as absolutely cheaply as possible, and it sounds like some of those building were just fleabags that very poor people could rent who didn’t mind living in just a shithole as a place to sleep. Kim constantly talked about them being high and drinking, which doesn’t lend itself to moving very quickly (laughs).

MT: (laughs) I guess it was more like people were reclined on their opium dens.

TCJ: Either that or everyone was drawing.

MT: Yeah, and once in a while rousing themselves to go out to the Exploding Plastic Inevitable or something. What’s cool is that if you talk to people, what is left in Manhattan are all these great stories that people have who do still live there, and sometimes you ferret out people who’ve been there for like thirty years with rent control and they do have amazing stories.

TCJ: I’m pretty sure Art Speigelman still lives in the SoHo area.

MT: Yeah, he still lives there, Kim Deitch lives in Manhattan. There’s a handful of artists that I can think of who do still live there.

TCJ: Does Gary Panter live in Manhattan?

MT: He lives in central Brooklyn.

TCJ: Let’s talk about him for a minute. You list him as one of your art heroes, and in terms of his impact on your work, I actually see it as kind of subtle. You don’t really use his ragged line. Is it more his sense of humor, and the fact that he’s not tied down to any particular art form and does everything, is that the big influence?

MT: It would be hard for me to dissect exactly how he’s impacted me, but I think [it's] in his amazing openness, open-mindedness, and constant creation, transformation and growth. The fact that he’s now jamming in a hippie noise band as well as doing visual projects. Maybe people don’t talk as much about his writing, as much as his visual impact, but for me, the writing goes hand in hand with my favorite artists, and I think he’s an incredible writer. The way he creates a universe with its own language, people speaking in it, and it’s utterly convincing, you know, really, really influenced me. Also the way he runs words up against images in the sketch book drawings of his, I saw those really early, in the RAW book, and that fracturing of the words against the image really affected me. I am also bowled over by his drawing, but maybe I’m trying not to be so under his spell (laughs).

TCJ: I’ve seen your list of things that have influenced you, and it’s a really disparate list, and it’s understandable, because it’s hard to pin you down. I look at your work and I don’t see a single dominant influence in any way, shape, or form. Another influence you talked about and I want to go into more detail is Fort Thunder. You talked about seeing Paper Rodeo back in 2000. What strips in particular caught your attention when you saw them, which artists?

MT: Let me see, when I saw it, it took me a while to identify artists as even being separate from one another.

TCJ: Yes, that’s understandable.

MT: It was kind of like hieroglyphics or the Rosetta stone or something. It was a bunch of marks on this newsprint and you’re just trying to decipher [it]. I’m still, oh, that guy drew that? You know, I’ve found out things ten years later, but the most immediate ones that I reacted to were probably Brian Chippendale's and Mat Brinkman's and Leif Goldberg's and Seth Cooper's Zissy and Rita, which I think is actually of all the strips that appeared in Paper Rodeo, an incredibly under-discussed, incredible strip.

TCJ: I’ve never seen it discussed, actually.

MT: Oh, it’s so funny, it’ so funny! It’s just like this scratchy, wonderful narrative of these two girls, one’s like a burned out little goth girl, and the other is like a sort of more [of a] Shirley Temple-like normal girl, and they just sort of have adventures. It’s very free form, but it’s a lot more linear than the other stuff, where it really feels like you’re breaking into some cave of coded characters. It took me a lot longer to decipher CF’s stuff and Ben Jones’s stuff as being like separate from the others. And I'd be like, "Oh, it’s that guy", you know? Chippendale’s [got] that overall textured mark-making, and then I think of the kind of rush of his narrative. Brinkman’s stuff, maybe I was able to figure out from the first. Leif Goldberg always astounds me, he’s really [a] visionary. I don’t know how to describe how he tells stories, it’s like a floating zoo mist.

TCJ: I have trouble holding onto it for that very reason, it’s kind of ethereal, which is not to say that I don’t like looking at it. I just have trouble parsing it sometimes.

MT: Parsing it, yeah, it’s not even parsable. For me, it’s another thing with the language and the image constantly pushing off from each other springboarding off into a different association and that’ll change what he draws, so he definitely uses his own logic tools and the fun is trying to follow it, I think.

Influences: Gaming

TCJ: One thing that interested me that you talked about that was being really into gaming and Dungeons & Dragons. It’s almost staggering to me how seemingly almost every [male] cartoonist under 35 played D&D, almost without exception. Was the narrative aspect of gaming something that appealed to you?

MT: When I found out about D&D, I was 7. And I immediately wanted to know about it. It was a magical thing that was being invented for adults and that children picked up on. All my friends picked up on it and it was before video games, or simultaneous with them. I got the box set first, it was these red saddle-stitched books that came in a box with the dice. Later, I got Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. I started buying those books at the used book store, and I collected them, and amassed them, and my friends on the island did too. I was into mapping and writing my own modules and adventures, so yeah, I think that gives you an amazing spatial sense of constructing stories and it’s just super fun, if you’re a writer, everybody’s writing at the same time, you know, writing an adventure in real time at the same time.

TCJ: Did you ever play characters, or were you always the Dungeon Master?

MT: Oh, I played characters, yeah. Different people had different styles. My friend Tom would Dungeon Master out of his head. It would become these great extended jokes, where a guy with anthrax was running after you, trying to piss on you or something. Or you discover a truck, and that can’t happen in D&D. I would be too uptight to let that happen in D&D, but other people would be the storyteller, so they’d allow stuff like that to happen. I dunno, I was very caught up in the arcana of it all.

TCJ: You liked the rules.

MT: Yeah, I liked just reading it, all the books, and all the rules & all the scores & all that crap (laughs).

TCJ: You list Erol Otus as an artist that you liked. Those Monster Manual books were really interesting to look at as a kid. What impact did the art in those books have on you? Is that something you really noticed and tried to copy?

MT: It was like a pinnacle of serious art or something (laughs). When I was that age, I wasn’t looking at Michelangelo or Leonardo Da Vinci; it was the coolest art that was available to you. Now, I really respect Erol Otus and his totally baffling color schemes. I guess he’s like a miniature figure painter now. I’ve looked him up on the internet, I don’t think he’s that active anymore. They’re almost like regional drawing styles, I don’t know where they plucked these guys out of! The illustrators who did Warhammer, too, had this amazing Bruegel-esque style of drawing. The people who did the Warlock on Firetop Mountain role-playing books, they had this weird European grotty rat-catcher style. I don't what they were looking at, but I’d be interested.

TCJ: In retrospect, I always got the impression that the D&D artists were really influenced by underground cartooning.

MT: Like S. Clay Wilson, maybe?

TCJ: Yes.

MT: Yeah, that makes sense. Well, if you look at the names of all those monsters in the book, they’re all drawn from dictionaries of mythology and stuff, they would just repurpose the names to make up their own creatures. So I feel like they were scholarly in their own way, and I think the people who did Warhammer definitely were looking at old prints from Albrecht Dürer for sure. And then, in England at that time, there was this weird, magical subculture that extended into the drawing of Nick Blinko from Rudimentary Peni. It was an anarcho-punk band, and he did this scribbly sort of gothic artwork that's really beautiful and I guess he's schizophrenic. So when he stopped taking his medication he created this black and white line artwork that's intense, just really intense and it draws from that fantasy stuff.

TCJ: Interesting. Well, I was kind of thinking about the D&D guys for the cartooning influence, because the art in those books is really different from other fantasy art of that period, like it has nothing to do with Frazetta or the Hildebrandt brothers, that super-airbrushed, hyperrealistic style. The line weight is very different--some people have a really wispy line and even some of the illustrations almost have a narrative quality to them, for some of the artists.

MT: Yeah, I think they were working so closely with the writers that they were trying to depict the creatures and the classes of characters very authentically. They were like "I'm going to draw a 17th level Paladin and you will know what it is from my drawing." Maybe it's a more wussy, more realistic...they were trying to conceive a whole aesthetic universe.

(continued)