JB Brager’s work across media explores identity through the lens of politics, media, history, and technology. Working primarily in short form to date, their work is dense with lived experience and teeming with humanity. They are equally proficient at conveying a sense of time and place in their autobiographical work as they are in simplifying complex issues in their editorial work.

JB Brager’s work across media explores identity through the lens of politics, media, history, and technology. Working primarily in short form to date, their work is dense with lived experience and teeming with humanity. They are equally proficient at conveying a sense of time and place in their autobiographical work as they are in simplifying complex issues in their editorial work.

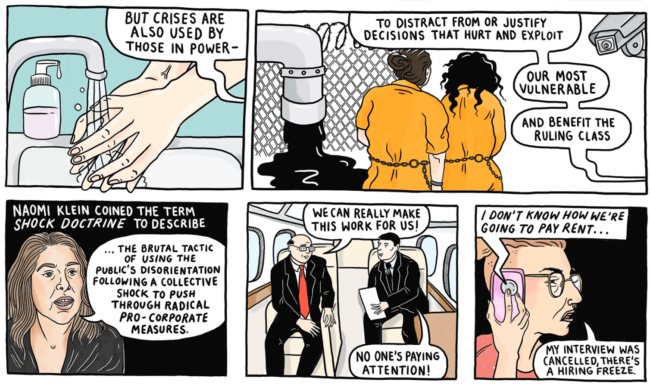

Presenting thoughtful work with an often DIY aesthetic, their work reads as reflexive, innate, but also deeply considered. As radical approaches to existence, long simmering, bubble to the surface of the cultural conversation, Brager’s work offers confident guidance that educates and espouses without condescending or conceding hard-won ground to make the ideas presented therein more palatable to a mainstream audience.

JB Brager holds a PhD in Women’s & Gender Studies from Rutgers University New Brunswick. They are an educator, cartoonist, zine maker and illustrator. Their work has appeared in a variety of outlets and anthologies, including The Nib, the Jewish Comix Anthology, The LA Review of Books, and GUTS Magazine. In addition to their comics work, they are also a founding editor of Pinko Magazine. They have also led programs and workshops related on the subjects of comics, zines, social media, and photography at the University of Maryland, Rutgers University, Binghamton University, Manchester Metropolitan University, Red Emma’s Bookstore, and Chicago Zinefest. Brager designed Graphic History, a public history workshop focusing on how comics are used to teach history. They will teach the course at Rutgers University in the fall.

Ian Thomas: Have these quarantine months been okay for you? Have they been productive from a comics and illustration standpoint?

JB Brager: Since Covid-19, things have been emotionally and logistically tough, needless to say— like most artists, I’ve been hit by the cancellation of comics events and also been super worried about my community and the world. But comparably, I think I’m doing alright. I haven’t been incredibly productive in terms of comics except that I lost my full-time job before Covid-19, so I have had a lot of unemployment time to eke out a few projects, in between applying for jobs. I’ve done two comics for The Nib, one for Jewish Currents and one for World War III, and I did a piece for the International Whore’s Day zine. And I’ve been very slowly piecing together a book project, that has not seen the light of day yet. I also have been trying to do pieces for community organizations like Third Wave Fund and Hacking Hustling, and to do some mutual aid work as well.

Can you talk about your earliest experiences with comics?

I grew up reading the funny pages, I really love Doonesbury for example… but I didn’t really encounter or get into comic books or graphic novels until college, when I started going to Big Planet Comics in College Park, Maryland. Good comic book stores are really important to browse and discover new work. Also, while I was at UMD I started drawing political cartoons for the school newspaper, and started making my zine “Sassyfrass Circus,” which is where I published most of my comics for a long time. I was very into DIY, self-published work, so it didn’t even really occur to me until much later to pursue placing comics in other publications.

One of the first graphic books I read was Lynda Barry’s Cruddy, which I got really early on, like in middle school maybe, and was obsessed with. When I was in college, I went to see her, Alison Bechdel, and Chris Ware on a panel at the Sixth and I Synagogue and after, I went to get a book signed by her. I walked up and Lynda Barry was like, “you’re an artist aren’t you” and I honestly have been glowing with recognition since that moment. Even though she probably just meant I was wearing funky pants or something, I still think about that a lot. The greatest disappointment of Covid-times is that I was supposed to take a class with Lynda Barry this summer. She’s just, honestly, the greatest.

What comics did you enjoy when you started reading comics? Were there comics that showed you some potential for the medium?

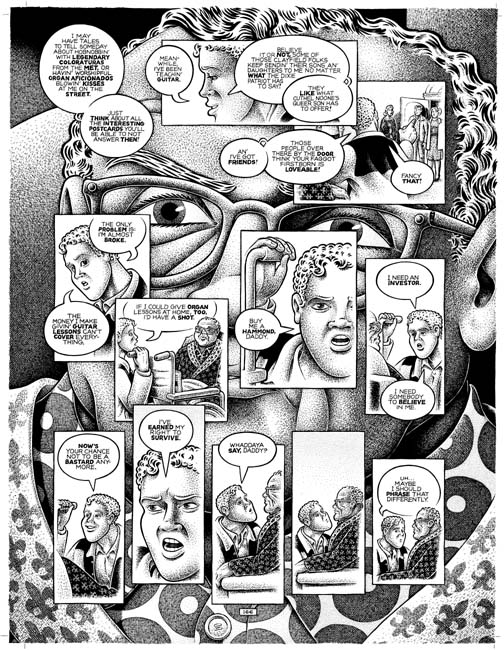

My entry into comics coincided with my entry into queer community, so I was really drawn to work like Diane DiMassa’s Hothead Paisan and Howard Cruse’s Stuck Rubber Baby. I love work that is different from anything I can do, like I’m really drawn to Edie Fake, Tommi Parrish, Simon Hanselmann— people whose work blows me away and I could never imagine being able to make. I also was very much into films before I was into comics, and comics of course are a pretty cinematic art-form. One of my weird introductions to comics was through Crumb, the 1994 documentary about Robert Crumb directed by Terry Zwigoff. Even though I was seeing very clearly some of the majorly problematic things about Robert Crumb’s work, I was really drawn to the weirdo outsider thing, so I went and bought a crow’s quill pen.

What creators do you count as influences?

My work is really didactic and somewhat autobiographical, so I turn to folks who do beautiful work in non-fiction, memoir, etc. like Joe Sacco, James Sturm, Bishakh Som whose memoir is coming out with Street Noise Press. Aline Kominsky-Crumb was a big early influence, I especially liked that she isn’t worried about her work looking a particular way, she draws in her own style and tells stories the way she wants to. I’m also heavily influenced by artists that I feel like I came up with in my community in Baltimore and Philly, especially Liz Bolduc, Olivia Horvath, Georgia McCandlish—people whose work I’ve admired and wanted to be worthy of.

When did you start making comics? What did your early efforts look like?

I started drawing comics around the time I started reading them, in college. Besides the political cartoons for the UMD Diamondback, I was primarily drawing short comics for my zine, “Sassyfrass Circus,” which I made mostly to trade for other zines. It wasn’t a mini-comic, it was a photocopied cut n’ paste zine that just had some of my comics in it. My early comics were, as I mentioned, influenced by Aline Kaminsky-Crumb, so I wasn’t caring as much about scale or proportion, I was just like, drawing what I wanted, but was very weirdly strict about using pen and ink on Bristol board. At some point, I think maybe in 2010, I submitted some three panel cartoon strips to the Baltimore City Paper and Emily Flake critiqued them as being essentially like Cathy, which felt insulting at the time and I think was meant to be.

Do you draw many distinctions between your illustration, zine, and comics work?

I feel more self conscious about illustration work because I don’t consider myself to be an illustrator— I’ll take the work as long as people realize what they’ll get is a comic without words. And zines are the vehicle not the medium— some of my zines have comics in them, others, like Doykeit, which is a submission-based zine about queer anti-Zionist Jewish identity and organizing, is mostly text.

You hold a PhD in in Women's & Gender Studies. Obtaining a PhD is a rigorous process and I wonder how comics and zines and art-making figured into it (if they did at all). I suspect they could be a release or a distraction or maybe both?

When I decided to get a PhD, the research I was interested in doing felt like the most pressing thing—now, post-PhD, I’m thinking about how to take all that material and distill it into comics. I do a lot of different kinds of work, and do a lot of writing that isn’t in comics form— even now, I have a piece coming out in Pinko Magazine, and a peer-reviewed one in a visual studies journal—but it all tends to be about the same things.

I don’t see comics or zines as disconnected from the academic work, or my work as a teacher. I guess I feel driven by questions and then use a bunch of different mediums to try to answer those questions for myself. The biggest thing is that I’m constantly trying to juggle all the different projects I commit to, and also trying to figure out how to make a living, which before looked like being a full-time history teacher and currently looks like working on a moving truck, and in the future who knows. Universal healthcare would help.

Do you tend to work digitally or on paper? With regard to layouts, on a comic like "LiveJournal Made Me Gay,"was it laid out vertically to facilitate digital display? I feel like each panel stands on its own very well and I wonder if that is by design. Was it made as a series of one-panel strips?

Since I start from a question or idea, I usually write out my comics as a script before I draw anything, and then go through the process of thumbnailing or doing rough pencils before I draw the comic. I’m definitely more driven by my own thought process than by trying to move through a series of events in my comics. Usually, honestly, not much happens. I’m trying to challenging myself to draw more step-by-step movement through time, with less exposition.

I’m increasingly figuring out how to work digitally because it’s so much easier to change things, but I’m not really a master of Procreate— I prefer working on paper and usually end up either pencilling on paper and then scanning into Procreate or pencilling on procreate and then printing out the pencils. Often the layout is determined by the publication, like The Nib has specific specs for sizing so that comics work on different size screens, things I’m bad at thinking about.

The self-published comic I did with Cesario Lavery, “My Gender is Saturn Return,” is a totally weird size because that’s just the size we drew it at, we weren’t thinking about it needing particular dimensions. You mentioned that “Livejournal Made Me Gay” works really well as a series of one-panel strips, which I thought was interesting. It wasn’t on purpose, but I do wonder how much I’m conditioned by Instagram to produce work that fits well into the grid, that can be accessibly shared.

Do you tend to prioritize theme over narrative (or vice versa) when putting comics together? I feel like your entire body of work is in service of exploring your identity and your experience. In this regard, is anything off limits? Do you draw any distinctions between the personal and the professional? For example, do you have any plans to recount your experience at Ethical Culture Fieldston School, when you were fired for expressing your political views on social media?

I joke that for an extreme over-sharer, people don’t know anything about me or my life. Honestly, most things are off limits. I’m coming up against that in this book project, which is in some ways a big extension of “Heavyweight” (Published in Jewish Currents). I don’t want to wound anyone or put my family’s business out into the world, unless it feels very pressing, or it feels like I have ownership over what I’m saying, or if I have permission.

Sometimes a piece will seem very deeply revealing, like I did a mini-comic called “Not Forever, Just Right Now,” which was a sort of meditation I did at the peak awful point of my divorce. But I didn’t actually include any details or say anything about my ex— in this sense, it wasn’t autobiography, it was just, like, the poetics of the event. You asked if I have plans to recount my experience at Fieldston; the thing about that is that I was very publicly dismissed and there’s no one involved who I’m afraid of hurting, so I do have some desire to tell my side of the story, and I am musing over how I might do that in the context of a larger project.

Can you describe your experience getting into long form work? What are some of the differences in your approach and what are some considerations you are making?

Regarding the move to long form work, it's pretty terrifying to commit to a big project that no one will see for a long time. Understanding that I have a short attention span and work in bursts (and consistently have like three jobs), I'm trying to conceptualize the bigger project as a lot of short pieces! I also have to think about what lets me work faster and in volume-- like I thought about doing it in full watercolor and then realized that I would probably give up after five pages if I did that.

Another thing is letting myself luxuriate in page length--the best thing about a book-length project is that you have space to draw stories out and let them breathe. Usually I have specs or constraints where it's like, okay, you have three pages-- and I end up cramming a ton of information into a small space, also because I'm impatient and writing is so much faster than drawing for me. Most of my comics are really dense with information!

I'm also trying to set up accountability measures for myself. One is that I'm currently taking the Graphic Novel Intensive course with the Sequential Artists Workshop-- having that online community has been helpful both for advice and also just to remind myself that I'm working on a book right now. And you know, telling a lot of people that I'm working on a book makes me want to actually finish it.

You recently announced that you will be teaching your Graphic History course at Rutgers University. What will this course in entail? Can you describe the process of creating a course and having it approved? In your experience, are comics and zones perceived in academic circles at the moment?

You recently announced that you will be teaching your Graphic History course at Rutgers University. What will this course in entail? Can you describe the process of creating a course and having it approved? In your experience, are comics and zones perceived in academic circles at the moment?

I’m still hammering out the details for Graphic History and how it’s going to look this fall, since classes will be online, but the gist of it is that it’s a public history workshop, about how we learn about history with and through comics.

There’s a lot of serious research on comics happening in academia; the work of Ramzi Fawaz particularly comes to mind, but in general we’re pretty firmly past the idea that comics are not to be taken seriously. Rebecca Hall is putting out a graphic novel based on her dissertation on women-led slave revolts. Even like, Kiku Hughes’ new book, Displacement, is a time travel fiction book set during Japanese internment, but she did some really interesting historical research for it. Venues like The Nib are putting out fantastic, accessible short work. There’s also a lot of really boring or sloppy educational comics floating around.

There’s a lot of exciting work happening and a lot of room to do cool stuff, and I want history students to be engaging with that on the undergraduate level. Maybe this means they leave the class with the ability to use comics in a history classroom, or to have a level of comics literacy that they can use to read comics as primary sources. Maybe they leave with the skill-set to write their own comics about history. It’s a pretty great opportunity to marry two of my areas of work, and I am super happy to get to do that.

There’s a lot of exciting work happening and a lot of room to do cool stuff, and I want history students to be engaging with that on the undergraduate level. Maybe this means they leave the class with the ability to use comics in a history classroom, or to have a level of comics literacy that they can use to read comics as primary sources. Maybe they leave with the skill-set to write their own comics about history. It’s a pretty great opportunity to marry two of my areas of work, and I am super happy to get to do that.

Can you speak to your considerations and selections in preparing the course syllabus?

Okay, so, my syllabus is shaped both by the goals of the semester--we'll be looking at everything from comics produced to be educational, comics as primary sources, memoir comics and historical fiction--and by the comics that I own and that are meaningful to me-- students are going to be doing a lot of their own exploration, so I decided that it's okay for the examples that I give to not necessarily cover every single topic of history. Because I'm teaching online and working with my personal library! Like a lot of faculty, I made an ethical call that I don't want to ask my students to buy books this semester-- so we'll be reading short excerpts from a lot of different texts.

Most of the comics I have are about radical politics and Jewish culture, or thankfully are educational nonfiction comics since that's a big area of interest for me. I'm still on the fence about assigning Maus, Persepolis, and March, since I'm fairly sure those are the comics students will have encountered, but they probably are less likely to have read, for example, Gord Hill's leftist history comics. We'll definitely be looking at Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atomic Bomb by Jonathan Fetter-Vorm, A Bintel Brief: Love and Longing in Old New York by Liana Finck, Berlin by Jason Lutes, Inhuman Traffic: The International Struggle Against the Transatlantic Slave Trade by Rafe Blaufarb and Liz Clarke, Footnotes in Gaza by Joe Sacco, The Machine Never Blinks: A Graphic History of Spying and Surveillance by Ivan Greenberg, Everett Patterson and Joseph Canlas, and This Place: 150 Years Retold which is a collection of histories of Indigenous peoples in Canada. We'll also be looking at a bunch of comics from The Nib, and Kate Beaton's Hark! A Vagrant, and then also analysis texts like Black Comics: Politics of Race and Representation edited by Sheena C. Howard and Ronald L. Jackson II. Oh, they'll also be reading Scott McCloud, duh. But I'm still finalizing the list for this semester and I'm sure it'll change drastically again for the spring semester.