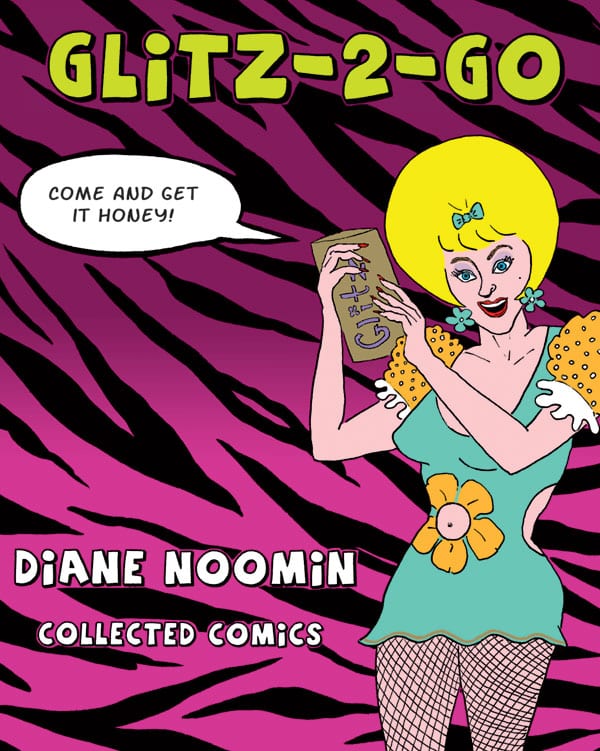

At first glance, DiDi Glitz’s life is nothing short of fabulous: a high percentage of “fascinating devastating love affairs,” “lavish interior design schemes,” and “utterly gorgeous outfits.” But DiDi wouldn’t be half as exciting if that were all there was to her. Formed in the crucible of the underground comix and women’s movements, she is equal parts sex, anxiety, domesticity, and rebellion—by turns a garish, boozy mess and a modern, self-affirming woman. Yet other than a onetime stint as a Halloween costume, DiDi has no origin story; she sprang fully formed, in 1973, from the mind of Diane Noomin. Since then, the two have been ready partners in crime—from robbing banks to mining friends’ revelations for comics material to dishing out tough personal advice. But it’s only with the publication of Glitz-2-Go, a collection of thirty years of DiDi stories, that Noomin and her alter ego get their due.

Noomin, born in Brooklyn in 1947, may be best known as an early contributor to Wimmen’s Comix and as the founder, with Aline Kominsky-Crumb, of Twisted Sisters Comics, in 1976. In the same period, her work appeared in a who’s who of underground publications: Weirdo, Arcade, Short Order, Young Lust, Titters, and more. But her career has also been devoted to celebrating the work of her fellow cartoonists; she has edited three anthologies, two of them—Twisted Sisters: A Collection of Bad Girl Art and Twisted Sisters: Drawing the Line—in the past decade.

Noomin’s talents extend off the page as well. In 1981, she put DiDi to work onstage, in a production with Les Nickelettes theater group called “I’d Rather Be Doing Something Else: The DiDi Glitz Story.” The costumes—fishnet stockings, gold lamé pants, and leopard-print rompers—were courtesy of Noomin, and the backdrops were created by friends, including her future husband, Bill Griffith. The year before, Noomin herself donned the blonde bubble wig to film an episode for the “Zippy for President” series produced by San Francisco’s KQED. At the close of the episode, DiDi and Zippy wake up in bed together, in what may be the most surreal cross-comics hookup.

I met Noomin for lunch last month on Manhattan’s west side, while she was in town for an event in conjunction with Yeshiva University Museum’s “Graphic Details: Confessional Comics by Jewish Women,” an exhibition that includes Noomin’s work. Midway through our conversation, a semi truck ambled down Ninth Avenue and eased to a stop at a red light, just in front of the restaurant’s windows. On its flatbed reclined a thirty-foot gold-painted statue of David, his gaze heavenward. DiDi most certainly would have approved.

Did you study art in school?

I went to an art school for high school—the High School of Music and Art in New York—and at Pratt, I took photography and sculpture courses. I wound up working in the Pratt library, in the art section. So I’m pretty familiar with art history.

Did it work its way into your early cartooning?

No, I think my cartooning had to work its way through the art, because when I went to school, they were trying to turn everybody into Abstract Expressionists, Jackson Pollock juniors. They once showed us a film where somebody was throwing paint onto a canvas on the floor and then rolling balls into it, and this was High Art! The worst thing you could be was illustrative or narrative, which of course defines comics. They told you how to look at art—you’re looking for the movement and all this stuff. In order to be a cartoonist I had to try to forget all that. I had a student pass to the Museum of Modern Art, and I’d cut class and try to look at art the way we were taught to.

When did you start drawing?

I think I’ve been drawing my whole life. When I was a kid I used to trap friends, cousins, my sister into drawing contests, because I knew I’d win.

Were you interested in cartooning when you were at art school?

No. I loved comics. I grew up reading comics. I loved Little Lulu, Uncle Scrooge, and whatever comics books I could get my hands on, but I never contemplated being a cartoonist. It never occurred to me.

Why not?

[Laughs.] I have no idea!

But that changed when you met Aline.

When I went out to San Francisco in 1972, I carried a little black notebook, where I wrote a lot of poems and made doodles and drawings. So I was heading to cartooning without realizing it. I showed it to Aline at a party and she said, “We’re starting Wimmen’s Comix. You should come down.” The first issue of Wimmen’s Comix was being finalized, so I wasn’t in the first issue—I was in the second issue—but I was in on it from the beginning, and it was very exciting. Suddenly I realized the whole world was material. I could do comics about anything!

How difficult was it to do your first strip?

Actually, it wasn’t difficult at all. I didn’t include it in the book because it’s kind of a continuation of an illustrated poem, and that’s in Women’s Comix, no. 2. Then, in Wimmen’s Comix, no. 3, I started to get more satirical, critical. That story was called “The Agony and the Ecstasy of a Shayna Madel.” That issue of Wimmen’s Comix was the part of the impetus for Twisted Sisters—Aline and I were getting very fed up with the politics of the women’s comix “collective.” That’s in quotes.

Sharon Rudahl, a Jewish woman, was the editor, but basically the editors did all the shit work, and Trina [Robbins] pulled the strings behind them. That was my perception. Anyway, Trina was Jewish, Sharon was Jewish, and I handed in “The Agony and the Ecstasy of a Shayna Madel.” Aline did a “Goldie” story, and Sharon told her that they had too many Jewish girl stories in there and they rejected it.

Is that when you and Aline broke with Wimmen’s Comix?

I think it took a little longer, but there was a lot of in-fighting and a lot of really unpleasant stuff that was going on in Wimmen’s Comix aimed at Aline and me.

Why you two in particular?

I think it’s because we had famous boyfriends. This was a feminist collective and some people—mainly Trina—had a lot of trouble getting into comics they wanted to get into, like Zap or Young Lust, and they felt they were being kept out by the boys’ club. That hostility got transferred to us, since Robert did Zap and Bill did Young Lust. The funny thing was that almost all of the women had cartoonist boyfriends. Every single one that I can think of, including Trina—and that wasn’t an issue. Then Trina got a friend of hers to write an editorial in the Berkeley Barb basically calling Aline and me “camp followers”—whores. The writer was the girlfriend of the cartoonist Guy Colwell. I once was so pissed off about the “camp follower” thing that I made a list of all the male cartoonists who were connected to women cartoonists.

Did you think there was a boys’ club?

I don’t think I really thought about it in those terms, because I was lucky—everything fell into place for me. I didn’t have that experience. I think it’s a valid experience that Trina had—I’m not saying it wasn’t—but I didn’t have it. I don’t think Aline had it.

So we just created our own comic. We went to Last Gasp and asked Ron Turner if he would do Twisted Sisters. It was just Aline and me. She did the front cover, I did the back cover, and we each did a story as long as we wanted and that was it.

Were there good things about being in the collective?

The good thing was getting work in print. The bad thing was that people didn’t notice it.

How was it distributed?

In head shops and wherever underground comics were distributed. I think it’s better known now, even though it’s out of print, than it was then. I’ve always thought that, aside from the small distribution, one of the problems was quality. When I did Twisted Sisters: A Collection of Bad Girl Art for Penguin, I got all these people saying, “Where did all these great cartoonists come from? Where were all these strong women cartoonists?” A lot of them came from Wimmen’s Comix and Weirdo. Weirdo got more attention, but the good stuff in Wimmen’s Comix was drowning in the bad stuff, in my opinion.

What do you mean by the bad stuff?

There were very strong cartoonists who published work in Wimmen’s Comix, but—I’m not very diplomatic—there were also comics in there I didn’t like and that weren’t up to the same standards as the really strong stuff that I chose for Twisted Sisters. And I think that was proved to be true because when it was separated, it really stood out, and people started paying attention to Krystine Kryttre, Mary Fleener, Penny Moran Van Horn, and Julie Doucet. Julie did a great story in Wimmen’s Comix that we reprinted in Twisted Sisters, about drowning the city in menstrual blood. Wimmen’s just didn’t get enough attention. I think Weirdo got attention in the comics world because it had Crumb covers, and that helped.

What was the relationship between women cartoonists and men cartoonists at the time?

I had no problems. I really didn’t. When I went out to San Francisco, it was kind of a “wild and crazy” time, and someone would throw a party when they published a book. I remember when Insect Fear came out, there was a huge party with kegs of beer and everybody was dancing—it was fun. When I first got there, I met Bill and Art Spiegelman and cartoonist Michelle Brand. Michelle was nice and really helpful. She was married to another cartoonist, Roger Brand. I wouldn’t say that Roger was helpful because Roger was just in his own world, but Michelle was, and Art was very helpful, very supportive, and so was Bill.

In a way, it was like Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney saying, “Let’s put on a show, kids.” If you wanted to, you’d say, “Let’s put on a comic, kids!” and you asked all the people you liked to be in it. Bill and Art had started Arcade and I was inspired. I wanted to edit a comic book, so in 1978 I edited a comic book called Lemme Outta Here!: Growing Up Inside the American Dream. It has a cover by Michael McMillan and a back cover by MK Brown, it has long stories by me and Aline, and Bill did a story called “Is There Life After Levittown?” And Crumb did a story about Treasure Island. Robert was obsessed with Treasure Island when he was a kid. I just asked cartoonists I liked if they’d be in a comic book and they said yes.

But there was a very strong need for feminism across the board in this country. When I was looking for work after high school, there were jobs called girl Fridays, and there were separate want ads for men and women. Hillary Clinton could not have run for president. Even though Geraldine Ferraro did later run for vice president, it was still a shock. I think a lot of younger women don’t have to think about it today, so that earlier stuff can come across as strident, but that wasn’t my interest in doing comics. My interest was in personal stories.

But I didn’t have that experience of not being able to get into comics. It seemed to me if you wanted to and you did enough work, you could ask a publisher and they would put a comic out. There was a time when it was easy to get things published, and Wimmen’s Comix was during that time. It’s also been a very long-lasting title, and I’m grateful for all the work I got into it. I was surprised at how much was there. And in Weirdo. Weirdo first was edited by Crumb and then by Peter Bagge, and then by Aline.

Had you read the underground stuff before you started doing your own work?

I read every comic I could get. And when I lived in New York and a new Zap came out, it was a huge deal—Far out, let’s read the new Zap! Let’s get stoned!

What made you move to San Francisco?

I had separated from my first husband, and I decided that the Upper West Side wasn’t far enough from Brooklyn.

Also, I came back from the summer of meeting Aline to my one room, fifth-floor walk-up on the Upper West Side, and to a shrink who told me that I should not go to San Francisco and draw comics, I should stay where I was and put bars in my windows and deal with all my issues about men. And I said, “I’m going to California!”

Your issues about men?

I didn’t like that guy. I had a shrink I really liked, a woman, and she—I always intended to do a story about this—she ran a group-therapy session. This particular group had rules, like you don’t know last names and you don’t fraternize outside the group. But then she left—she said her husband got a job in Washington D.C.—and we all took it badly when she recommended this guy to take over the group and do personal therapy. And when he did, chaos reigned. I had an affair with a guy in the group, and then another woman in the group had an affair with a guy in the group, and we started having meetings at our houses without the shrink and serving drinks and the whole thing turned into anarchy. [Laughs.]

So you went to San Francisco and met up with Aline again.

Yeah, I had relatives who lived out there, so I lived with them for six months before I found a place on Clipper Street. My roommate was Lela Janushkowsky, who was Kathy Goodell’s best friend from high school. Kathy was Robert Crumb’s girlfriend for a very long time. She was an artist and sculptor and she was not happy about Aline’s relationship with Crumb.. So I was Aline’s close friend and I was living with Kathy Goodell’s best friend. It was interesting.

That must have been complicated.

It was fun, though. Lela was a good-time girl. I’d never lived with a good-time girl, so I went along in her wake sometimes.

How did DiDi come about?

She started as a costume for a Halloween party at Gilbert Shelton and Lora Fountain’s house and quickly took over. There’s photo of me in DiDi drag in “Canarsie Creeps” in 1973. It’s an eight-pager—we used to call them eight-pagers. A lot of people were putting them out. Justin Green did one, Bill did one, Art Spiegelman did them. Everybody, just for fun, was putting out these eight-pagers that sold for seven cents and were two 8 ½ by 11 sheets of paper that were folded four ways and configured so you had eight pages.

In 1974, I did a full-fledged DiDi story for Wimmen’s Comix. It was four pages and was called “She Chose Crime”, and when I was putting this book together I realized that DiDi came out almost fully developed. She hasn’t changed, she hasn’t grown or anything like that. If I look at that first story, the drawing has changed and I’d like to think that certain things have gotten better, but in that story, DiDi’s persona is it. I don’t think I’d realized that.

How did she make it from costume to cartoon?

I put myself in the costume in “Canarsie Creeps”, and then, as I was drawing comics, I was influenced by a photograph of what looked like complete desolation in suburbia by a photographer named Bill Owens. Titters, which was an anthology put out by Deanne Stillman and Anne Beatts in the early seventies, I published a two-row strip about DiDi describing her décor. It’s called “I’d Rather Be Doing Something Else”. So that was my first DiDi strip, but very soon after that came “She Chose Crime”.

I could never understand how Aline could be so autobiographical. Aline’s method was, “I’m going to say everything bad about myself that anybody could say before they say it and put it in my comics.” It’s basically like, “Fuck you. Yes I’m with Robert Crumb, yes, my drawing doesn’t look like his.” I was incredibly impressed by that. And she was very influenced by Justin Green.

They were the first two to start doing autobiographical work. She was the first woman.

She gives Justin credit for that. Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary had a powerful effect on her. For Aline, that was just a natural approach, and for me, DiDi became the natural way to do things. I could do satire and use real-life situations and have DiDi experience them in her way, so that I’m one step removed. It took a long time for that to change, although there were intervals along the way where I did do personal stories, like “Coming of Age in Canarsie” or “The C-Word”, about abortion—C, at that time, meant choice.

That was for a pro-choice book that Trina Robbins edited, it was a very hard story to do, because I had had an abortion soon after the affair with the guy from my group, who had a long blond ponytail and wore black leather pants. But I didn’t know who the father was. It was a confusing time. It was after I had left my husband.

How hard was it to get an abortion then?

It was the first year it was legal, so it was not hard at all. I went to the Margaret Sanger Clinic, and everything was very above board and easy. Scarily easy.

Were there protesters?

There weren’t. Legal abortion didn’t have a high profile yet. When I was in San Francisco I was involved with a theater group called Les Nickelettes, and they did a play called "I’d Rather Do Something Else: The DiDi Glitz Story". As a group, we decided to do a benefit for Planned Parenthood—this was in the eighties, and there was a lot of demonstrating and fire bombing. When we were planning the benefit, we went to the Planned Parenthood offices in San Francisco where they had intense security and it was a little scary to be there. In San Francisco, of all places, I didn’t think it would be like that, but it was.

There’s a lot of sex in the DiDi comics.

There is. I was surprised at how much when I started to put Glitz-2-Go together,

But thinking about the time you did them, the mid-seventies, it’s not the kind of sex you’d expect to see from that period. It’s not feel-good, wild experimentation sex. DiDi can’t get an orgasm, and she can’t find a good lover. And in trying to solve her problem, she consults a woman’s group, where they talk about loving yourself.

It’s very San Francisco. In one of my favorite panels, a naked woman wearing rubber gloves jumps up out of a communal hot club shouting, “It’s my wrists, my gross, fat, disgusting wrists, gloves don’t help anymore...!” [Laughs].

But in the end she’s just completely true to herself. And the contact paper…

What could be truer for DiDi than riding contact paper to an orgasm?

I love that ending. Is that your favorite DiDi story?

It might be. I mean, I don’t really have a favorite but that’s a good, pure DiDi story. And it was fun. I got to send away for catalogs of vibrators.

The good kind of research.

Yeah.

How much does her lifestyle resemble that of Canarsie, where you grew up?

It wasn’t personally similar. I moved to Canarsie when I was twelve, going on thirteen, and I had to learn how to be a teenager in about two weeks because the mores were so different in Brooklyn. In Long Island, I was climbing trees, I was a kid. And in Brooklyn I was going to make-out parties, so it was pretty shocking. And my experience growing up in Canarsie was very different—but I wasn’t satirizing my family, I was satirizing the neighbors. We had a neighbor who had white shag carpeting, and you had to take your shoes off before you came into the house. I had seen the houses of my friends in junior high school, and then I went to Music & Art, and I became a real snob. Canarsie was so bourgeois. So, Canarsie did feed a lot of it.

My experience on Long Island was unusual for suburbia because my parents were communists. They moved to Long Island to go undercover, although they didn’t change their names, so I can’t figure that one out. They moved to an integrated neighborhood—what they and the Communist Party thought was an integrated neighborhood in Hempstead but actually was a neighborhood experiencing white flight, so more and more black people were moving in. It was a much poorer neighborhood, but I did end up having some black friends who protected me from other black kids who threatened to beat me up.

So I didn’t experience the kind of incredibly luxurious but fraught childhood Aline had. She lived in the five towns and had the cashmere sweaters and the Capezio shoes. I never had that.

When did you find out your parents were communists?

I got a clue when the FBI started questioning our neighbors in Canarsie, but we didn’t talk about it until I was in my thirties. I did know during the Vietnam War, when I went to march on the Pentagon, that my mother was in Women Strike for Peace. So I knew they were left wing and liberal, and I was proud of them, but the commie stuff was all secret.

They were working for the Communist Party of the United States?

Yes.

(continued)