Little did I know that as I stood in a comic book shop on August 14, 2012, staring at a large collection of paper scrapbooks, that I was about to make a decision that would kickoff a seven-year obsessive journey for me.

I’d been a comic book collector for decades and, in recent years, had become an admirer of Milton Caniff, the classic comic strip artist who created Terry and the Pirates in 1934 and Steve Canyon in the 1947. It was because of the latter strip that I was at Victory Comics in Falls Church, Virginia that day, talking to owner Jeff Weaver about a complete set of Steve Canyon comic strips he’d recently purchased.

Looking back, it was a crazy set of circumstances and coincidences that brought me to that meeting.

In the early 2000s, I was going through one of my lulls in comic book collecting when I read Gerald Jones’ book, Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book, and Mark Evanier’s biography of Jack Kirby, Kirby: King of Comics. These stories about the early days of comic book publishing fascinated me. I was curious to read how the adventure strip artists of that era such as Caniff, Hal Foster (Tarzan and Prince Valiant) and Alex Raymond (Flash Gordon) inspired the first generation of comic book artists like Kirby, Joe Kubert and Will Eisner.

Something in particular about Caniff’s story appealed to me. Like me, he was from the Midwest. He had worked his way up from being a staff artist at the Associated Press in the 1930s to launching what would become one of the most groundbreaking comic strips of all time, Terry and the Pirates.

From Jones and Evanier’s books, I learned how Caniff revolutionized visual storytelling with an elegant chiaroscuro artwork and a compelling narrative that melded humor, melodrama and sex appeal.

Growing up, I remember my parents talking about Terry and the mysterious Dragon Lady and how exciting and daring it all was.

Two other books filled in the details that would really hook me on Caniff: Milton Caniff Conversations by R.C. Harvey and Will Eisner's Shop Talk. That’s where I first learned about the artist’s life-changing decision to leave Terry behind and create a whole new daily comic strip, Steve Canyon.

In this era of free agency in sports and high-priced entertainment, where athletes and celebrities routinely negotiate new contracts or jump from one team or medium to another, it’s difficult to imagine the perceived risk of Caniff’s decision.

Terry and the Pirates was huge. In the late 1930s, Caniff racked up a sizable audience by telling exciting tales of intrigue and adventure in Asia. His artwork was displayed in New York galleries, reprinted in comic books and adapted into a movie serial and radio series.

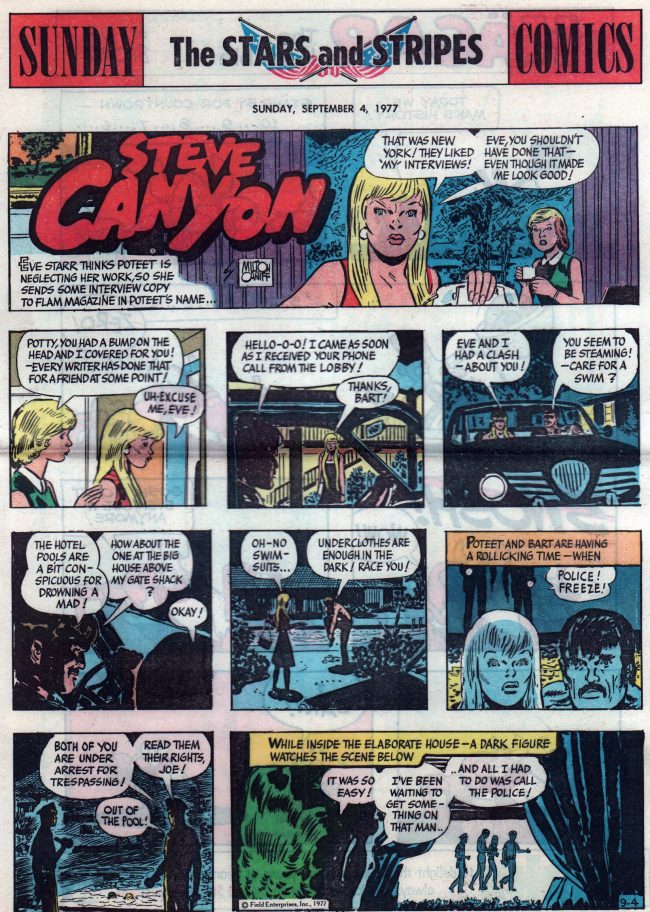

When America went to war in 1941, Terry and his friends were already fighting the Japanese invaders in China. Caniff adapted the strip to the war effort, creating characters that resembled the young men and women who had left their homes behind to fight. Many of these had grown up reading Terry’s exotic adventures. During the war, families on the Homefront could pick up the newspaper and see Caniff’s stories with soldiers, sailors and nurses resembling their own children who were thousands of miles away.

Caniff contributed to the war effort beyond his Terry stories. He provided the U.S. government with promotional materials and created the weekly Male Call comic strip for the Camp Newspaper Service.

from 1963-64.

Millions of people knew who Caniff was through all this exposure. By the end of the war, he was at the peak of his celebrity. That was the moment he decided to jump ship.

While Caniff’s artistic mastery and dedication had made Terry and the Pirates one of the most admired and read comic strips in the world, it was owned by the Chicago Tribune New York News Syndicate. Caniff was a salaried employee, albeit a well-paid one. Aside from his salary, he received royalties based on the strip’s circulation along with 20 percent of the licensing and merchandising of the characters he created. But, since the strip was not his, he could, in theory, be fired at any time if the syndicate felt like it.

the facing page. The sequence shown here is from 1964.

In his book Meanwhile … A Biography of Milton Caniff, R.C. Harvey recounts the 1945 meeting between Caniff and Marshall Field III, publisher of the Chicago Sun. Field was looking for content to boost circulation in his battle with the rival Chicago Tribune. A new comic strip drawn by Caniff would fit the bill perfectly.

Caniff recognized the offer as a chance to obtain creative independence and financial security for his future. When asked what he would need to leave Terry and start a new strip for The Chicago Sun Syndicate of Field Enterprises, Caniff said he wanted complete creative control and ownership. Field agreed.

To be fair, Caniff was not the first artist to walk away from a big property or ask for greater control and ownership of his work.

complete run of Caniffites/Caniffites Journal. Here are the first ten issues.

As early as 1940, Will Eisner struck a deal with The Des Moines Register and Tribune Syndicate to create a sixteen-page comic book supplement to be inserted in the Sunday comics section of the syndicate’s newspapers. Not only did Eisner oversee all of the content, he created the lead feature, The Spirit.

Part of Eisner’s deal was that ownership of the supplement’s contents would revert to him once the syndicate ceased publishing it, which it did in 1952. Thereafter, he was able to license reprints of The Spirit and other features.

Cartoonist Roy Crane took an offer in 1943 from the King Features Syndicate to abandon his strip Wash Tubbs — what many consider to be the first true adventure strip — to create Buz Sawyer, which he would own outright.

including these two Spanish-language strips from 1947.

When I first read about Caniff’s decision to leave Terry and the Pirates, I wasn’t necessarily shocked. As a comic book collector since the 1970s, I’d read many stories about artists and writers trying to wrestle ownership of their creations from publishers. Whether it was Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster with Superman or Joe Simon with Captain America, creator’s rights was a big topic of discussion among comics professionals and fans.

I admired Caniff for having confidence in his abilities and taking what, at first, many people must’ve seen as a terrible risk. Terry was a phenomenal success. Why turn your back on that?

Since Caniff could not work on the new strip until he’d finished his final installment of Terry, little was know about Steve Canyon until it debuted on Monday, January 13, 1947. Even so, the Chicago Sun Syndicate had been able to sign up 234 newspapers — a sizable number — strictly on Caniff’s reputation alone.

In short order, Steve Canyon turned out to be a hit. Caniff employed all of his storytelling gifts to generate excitement about his new hero, a World War II Army Air Corps veteran, who now operated a private air freight business. It was a more mature strip than Terry and the Pirates, capturing the postwar unease of veterans and their families transitioning back to normality as the Cold War began to loom.

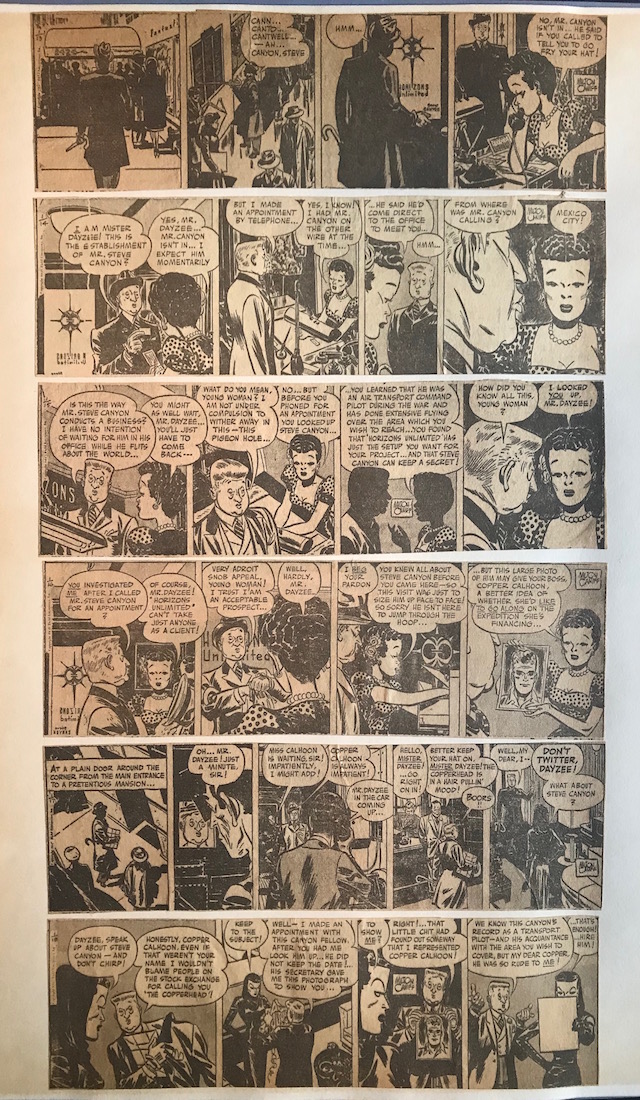

My first exposure to Steve Canyon came from reading the paperback reprints Cartoon Art Publishing released in the 1970s. I’d picked up the first two installments of the four-volume set around 2004 at a used bookstore. Despite the poor quality of the reprints, I found the stories mesmerizing. They had a real film noir feel to them.

At that time, I was also a fan of Modesty Blaise, Peter O’Donnell’s adventure strip. I’d already read O’Donnell’s novels featuring the character and Titan Books had just started publishing the comic strip in high-quality paperbacks. The one problem was that at Titan’s four-books a year release schedule, it would take more than a decade before all 95 comic strip stories were published.[1] I didn’t want to wait 10 years to read Modesty Blaise.

The funny thing is that even though Titan committed itself in 2004 to being the first publisher to reprint the entire Modesty Blaise comic strips series, all of the stories from the series had been reprinted in one form or the other over the years. Star Books published two paperback collections in 1978. Ken Pierce Books published eight comic book sized reprints in the 1980s. Titan itself had published eight volumes of reprints between 1984 and 1990. Most significantly, Comic Revue, a magazine dedicated to preserving the best comic strips of the past, presented serialized installments of the strip and published a Modesty Blaise Quarterly magazine.

members of the military and their families. On December, 25, 1954, he recognized the

sacrifices of newsmen who died reporting the news.

Discovering that alternative reprints existed, I sought them out and eventually amassed a complete set of Modesty Blaise stories. Within a few years, I was able to read all 41 years of O’Donnell’s comic strip work.

By the time 2012 rolled around, I was looking to recreate the experience I had in collecting and reading Modesty Blaise. While I knew NBM and later IDW’s Library of American Comics had reprinted Terry and the Pirates in its entirety, reading all of Steve Canyon appealed to me more, both as a collector and fan.

Thanks to all the issues of Comics Revue that I’d picked up in my Modesty Blaise quest, I had a pretty good idea of possible sources for Steve Canyon reprints. Unlike Modesty or Terry, though, it was slim pickings for Steve fans.

The earliest reprints came in 1948, when Harvey Comics published six comic books. Later, The Menomonee Falls Gazette reprinted contemporary strips in the 1970s, as did Comics Revue in the 1980s.

Kitchen Sink Press made a significant effort publishing 21 issues of Steve Canyon Magazine in the early 1980s, following it up with five paperback books. In total, Kitchen Sink reprinted all of the strips from January 13,1947 to April 7, 1958.

In 2006, Checker Books took a stab at publishing Steve Canyon from the beginning. The reprints, however, petered out after nine volumes, ending the run with a 1956 story.

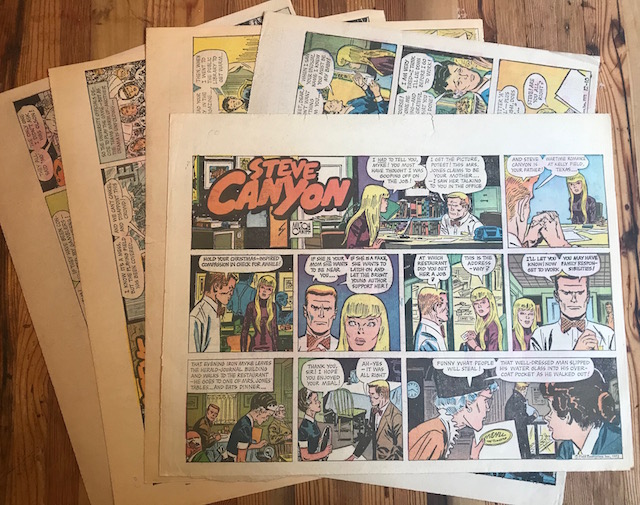

Building on the success of its Terry and the Pirates reprint series, IDW’s Library of American Comics published the first volume of Steve Canyon on January 31, 2012. Like Terry before, this new series would reprint two years worth of content in each hardback volume.

While getting a regular, high-quality reprint of Steve Canyon was good news, I couldn’t help feeling like I was in the same situation I’d been in a few years before when Titan began publishing regular reprints of Modesty Blaise.

Since I’d purchased all of the Kitchen Sink and Checker reprints, I had already read Steve Canyon up to April 1958. It was going to take six volumes before I got to read anything from the latter half of that year. In addition, if IDW published at a rate of two volumes per year, it would take more than 10 years to publish all 41 years of the strip.[2]

I was going to have to wait and that was incredibly frustrating.

This was my collector’s state of mind on August 14, 2012, when I was standing in Victory Comics in Falls Church, Virginia, looking at a complete set of Steve Canyon comic strips.

Even the series of events that led me to that comic shop was pure happenstance. The week before I was in Chicago with my family visiting relatives, when we decided to attend the first day of Wizard World. I’d been to many comic book and science fiction conventions over the years, and going to Wizard World seemed like a great way to spend one of our vacation days.

The problem with being an old collector is that you develop very narrow tastes in the things you’re seeking out at a convention. Unless your favorite writer or artist has a big new book, you tend to look for old or unusual items. Such was the case in Chicago, where I was looking for books about old comic strips or any Caniff-related merchandise.

At the Basement Comics booth, I noticed a copy of America’s Alertmen, which the Camp Newspaper Service published in 1943. On the cover was a drawing of Miss Lace, the heroine of Caniff’s wartime comic strip, Male Call.

I purchased the newspaper and asked Basement Comics owner Al Stoltz if he had any other Caniff material at the con. He showed me the original artwork for a Steve Canyon strip from 1964. I passed on it, but Stoltz mentioned that he had more artwork back at his store in Harve de Grace, Maryland. He added that it had come from a huge collection of Steve Canyon material that had walked into Jeff Weaver’s store in Falls Church, Virginia.

I laughed because Victory Comics is a 15 minute drive from my house. Incredibly, I’d traveled all the way to Chicago to stumble upon something like this so close to where I lived.

Weaver had also set up a booth at Wizard World and confirmed that he did have artwork and other material to sell, including a complete collection of Steve Canyon strips.

One week later, I was rummaging through four cardboard boxes and a stack of hardcover scrapbooks trying to determine if it indeed was a complete set of strips.

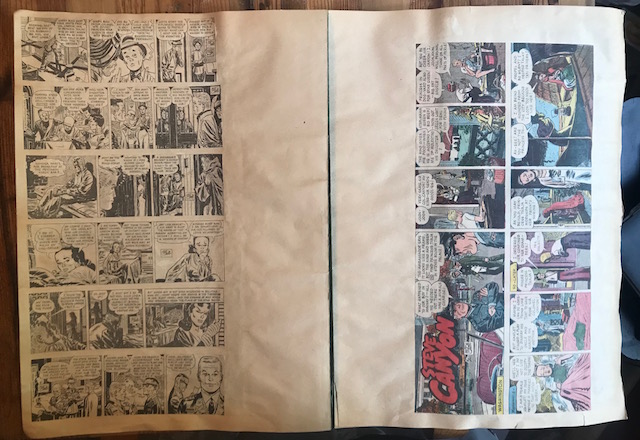

Most of the daily and Sunday strips had been pasted into thin, paper-covered scrapbooks, each having a number pencilled onto the front. In one of the larger scrapbooks, I identified the first week of Steve Canyon strips from January 1947. In another book, I found the Sunday strip for June 4, 1988 — a drawing done by cartoonist Bill Maudlin as a memorial following Caniff’s death. Everything appeared to be there.

According to Weaver, a local man had brought some original artwork by Caniff into the comic shop and asked if he’d be interested in buying them and other material that his father had collected over the years. Once Weaver assented, the man went back home and returned shortly thereafter with the boxes and other pieces of original art.

I was a bit astonished by it all. Imagine having the patience and dedication to cut out out a newspaper strip and paste it into a scrapbook every day for 41 years.

“It’s a real labor of love,” Weaver said, adding that there was a newspaper article in one the boxes about the man who collected the strips. Apparently, he had been a Coast Guard officer.

We struck a deal for the 80 scrapbooks, along with the miscellaneous material in boxes, and Weaver helped me load the items into my car.

When I got them home, I went through each box and confirmed that all 80 scrapbooks were present and accounted for. The pages from some of the older ones had separated from their bindings and started to crumble around the edges.

As a comic book collector, I recognized that my first priority was to stabilize the condition of the scrapbooks. Over the next couple of weeks, I ordered large mylar bags and acid-free boxes to store the scrapbooks in. I disposed of the old cardboard boxes, some of which were held together by masking tape.

What surprised me the most on that first day was how much other material had been crammed into the boxes. I found countless loose daily strips, full Sunday pages, a poster promoting ZIP codes on behalf of the U.S. Postal Service and newspaper clippings with articles about Caniff and comic strip art.

The most unusual item came in a blue paper sleeve. It was a large film negative of a Steve Canyon drawing by Caniff that had been personalized in 1958 to Mr. and Mrs. Richard A. Bauman.

Bauman was the Coast Guard officer whose collection I was now rooting through. He and his wife Dorothy had been featured in the Portsmouth Women’s News and Society page of the Virginian-Pilot on Sunday, on March 9, 1969. I found several copies of the article mixed in with the scrapbooks, along with 8x10 photos used to illustrate the feature. That’s where I first learned about the Baumans’ story, which I detailed in my previous story for The Comics Journal.[3]

I found myself in a unique situation as a collector. On the one hand, I had all of the Steve Canyon strips at my disposal to read. On the other, I had a great deal of ephemera Richard Bauman had amassed in his 40+ years of collecting.

Digging through the boxes, I recognized things that I might have had in my own collection — program books from San Diego Comic Con, comic books, newspaper clippings about Caniff or comic strip collecting, fanzines, ads from The Comics Buyers Guide, magazine articles, and mastheads from newspapers that published Steve Canyon. The collection was not just an assembly of strips, it was a snapshot of comic strip collecting from 1947 to 1988.

On top of that, thanks to the Virginian-Pilot article, I knew something about the collector and his relationship to his collection.

Dorothy Bauman had saved Steve Canyon strips for her fiancé back in 1947, so he wouldn’t miss out on the latest adventure while he was overseas with the Merchant Marines. When he returned, Richard Bauman started saving strips and continued to do so until the final strip in 1988. This daily ritual of clipping a strip from the newspaper and pasting it into a scrapbook, even while he was serving with the Coast Guard in Vietnam, commemorated Dorothy’s original gesture of love back in 1947.

The more I delved into the collection, the more obsessed I became about the Baumans’ story and sharing it with others. Before I could do that, though, I had to make the collection whole again.

Jeff Weaver had sold all seven pieces of Caniff artwork from the Bauman collection to Al Stoltz of Basement Comics. Stoltz, in turn, had already sold three pieces — two hand-colored prints, one of Miss Mizzou and the other of Steve Canyon[4], along with a pen and ink portrait of Richard Bauman from 1983— on eBay.

Eventually, I purchased the remaining artwork from Stoltz and tracked the Miss Mizzou print and Bauman portrait to a Canadian comic art collector named Jeff Singh. After I told him about the collection and my plans to write a feature about it, Singh agreed to sell me the artwork because he believed in the “karma of collecting.”

In addition to the artwork, Stoltz also sold me another box of materials he had obtained from Weaver. This contained a number of fanzines, including a full-run of Caniffites/Caniffite Journal; a Steve Canyon in China puzzle released by Jaymar (Circa 1952); Steve Canyon's Interceptor Station Punch Out toy from Golden Funtime Books (1959); a boys-size Steve Canyon T-shirt; trading cards; and various books and magazines, reprinting Steve Canyon and Terry and the Pirates. There were also a number of envelopes and letters from comic strip art dealers, which showed that Bauman was on the hunt for strips and original artwork in the 1970s and 1980s.

As a long-time journalist, I had occasionally written freelance features for magazines and websites, some that were focused on popular culture. I felt comfortable taking on this project, and, as was my practice, I wouldn’t write the article until I’d sold it to a publication. Before I could do that, though, I had to see if the Bauman family would give me permission the write the story.

In June 2013, I cold-called Robert Bauman, Richard and Dorothy’s son, at his home in Northern Virginia. After I explained who I was and the reason for my call, Robert was happy to talk briefly about his parents and the Steve Canyon collection. He put me in contact with his brother Richard A. Bauman Jr., who lived in Maryland, and his sister, Elizabeth Simpson in Florida. They were older and knew more about the collection.

I had long phone conversations with Richard and Elizabeth about their parents’ marriage and what it was like growing up in a military family in the 1960s and 1970s. They also shared memories of their father’s Steve Canyon collection and how important it was to him. They gave their blessing to my project, as long as I promised to be respectful to their parents’ memory.

As remarkable as Richard Bauman’s collection seemed, especially when you included the personalized artwork, I needed to determine how “unique” it was. To do that, I interviewed two Caniff experts: biographer R.C. Harvey and Bruce Canwell, editor at IDW’s Library of American Comics.

Both Harvey and Canwell found Bauman’s story to be interesting, but neither had ever heard of him. They confirmed that Caniff had a long history of communicating with members of the military, as a way to lend detail and authenticity to his storytelling. Harvey surmised that Caniff may have responded to the Baumans’ requests for original artwork to cultivate a relationship with a Coast Guard officer, who might one day provide information for a future story.

As far as whether the collection itself was unique — all 14,754 daily strips clipped from newspapers over a span of 41 years — Harvey acknowledged that he knew of one or two other complete collections out there. In fact, he borrowed segments of one to help with his research on the Caniff biography.[5]

Harvey and Canwell suggested that I visit or contact the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at The Ohio State University in Columbus, to help with my research. That’s where Caniff’s papers resided.

I did use the library’s online search tool early on and discovered that Richard Bauman’s name did appear in Caniff’s files. With the help of library staff, I obtained a copy of a letter from Capt. Neal Herbert, who was requesting Caniff draw a portrait of Bauman to commemorate his retirement as the Chief of the Office of Navigation at the Coast Guard Headquarters in Washington, D.C. There were also two thank you notes in the file from Herbert and Bauman.

Google turned out to be a valuable research tool as well. I found a copy online of Bauman’s 2005 obituary from The Washington Post, which had a lot of detail about his military career. It even mentioned the collection!

Bauman had also recorded an interview for the Veterans History Project about his 13-month tour in Vietnam during the 1960s. I paid a visit to the Library of Congress to listen to a digital audio recording of the interview. It was fascinating to hear Bauman discuss the mundane day-to-day experiences of living in a war zone, all delivered in a steady, unhurried cadence tinged by his New England accent.[6]

One other piece of online research involved contacting Bill Verge, executive director of the USCGC Ingham Memorial Museum in Key West, Florida. Bauman commanded the Ingham during the 1970s, when it was home-ported in Portsmouth, Virginia. When he stepped down from that command in 1973, Caniff drew a portrait of Steve Canyon saluting him. Verge confirmed that the signal flags on the drawing spelled out NRDL, the Ingham’s radio call sign. The large “E” on the image represented the ship’s efficiency rating.

With all of this research in hand, I put together a story pitch and started trying to sell the feature in early 2014. Even though I reached out to the comics press, military magazines and even general interest outlets, no one was interested in the story.

After this first round of rejections, I began to rethink the story I wanted to tell. I came up with a narrative that weaved together Bauman’s military service, his love of the Steve Canyon comic strip, Caniff’s support for the military and then later cooling off of the strip’s popularity during the Vietnam War. I wanted to contrast Bauman’s real world experiences in the military — many of which were quite interesting — with the fanciful adventures of Caniff's fictional Air Force officer.

Collectibles in the Bauman collection, but they passed on it.

This new narrative seemed like a perfect basis for a piece of comics journalism, in which I’d use a comic strip to tell the story of a comic strip fan and artist.

For several months, I worked with cartoonist Josh Kramer to develop this new project. He even came up with a few images inspired by Caniff’s Vietnam-era drawings of Steve Canyon. Unfortunately, things never really jelled and the project fizzled.

In 2014, I even tried to get another form of media interested in the story I wanted to tell. I brought some photos, artwork, letters and newspaper clippings to a recording session of Maryland Public Television’s Chesapeake Collectibles. I had a great conversation with an appraiser from the show, but the collection failed to make the cut.

My original project sat simmering on the back burner for a number of years. Occasionally, it would heat up a little, but then cool down again.

Every couple of years, I would run into Al Stoltz of Basement Comics at a convention and he would bug me about it. “When are you going to finish that project?”

“I don’t know,” I’d say. “Nobody wants to buy it.”

Strangely, it was Stoltz who sparked the oddest turn in my research. Out of blue one day, he texted me scans of several pieces of Caniff artwork from the Bauman collection. They’d turned up in an issue of the Nucleus fanzine without any attribution or explanation.

Stoltz and I pondered this peculiar development. How did this artwork, which was owned by a Coast Guard officer, end up in a fanzine from the 1970s?

While going through Bauman’s collection, I’d discovered that he’d written letters to a number of fanzines in the 1970s and 1980s. Perhaps he’d sent the artwork to Nucleus.

Looking at the fanzine's masthead, Stoltz discovered the publisher was Mark Wheatley, a Baltimore-based comic book artist and fantasy illustrator. He happened to have Wheatley’s email address, which he shared with me.

Wheatley and I exchanged emails, and then a couple months later, we had a conversation about Richard Bauman and his collection at Awesome Con in Washington, D.C. Back in the 1970s, Wheatley was a paperboy for the Virginian Pilot-Ledger Star in Portsmouth. He remembered the Baumans as subscribers on his paper route, and how Richard happily shared his artwork when the young fanzine publisher showed an interest.

“I think the other reason that they were willing to let me wander off with the art was that my mom taught one of their kids,” Wheatley said. “My mom taught third grade.”

Although Wheatley had never met Caniff, he did meet the artist’s assistant, Richard Rockwell, years later when they were both working for First Comics. Beginning in 1954, Rockwell pencilled the daily Steve Canyon strip based on Caniff’s rough layouts. Caniff would then go over the pencils with ink to create the finished artwork.

As a young fan, Wheatley wasn’t aware of this or that the Miss Mizzou and Steve Canyon images were actually prints and not original drawings. He was just happy to have some unique artwork to illustrate his fanzine.

Having known Rockwell since then, however, Wheatley suspects the assistant may have had a hand in creating the “Permission to come aboard” drawing Caniff sent to the Baumans when Richard was deployed to Vietnam in 1967.

“The ‘Permission’ piece looks like Dick's pencils, to me — and it would have been the right years for him,” he said. “But I've seen Caniff in video inking Rockwell's work and he only vaguely followed the lines. Mostly he was drawing with ink.”

It’s unlikely Richard Bauman knew that Caniff may have had help with this special drawing. Likewise, he may not have known that the personalized Steve Canyon and Miss Mizzou portraits were prints instead of original drawings. Based on the correspondence Bauman had with the artist, knowing the truth would not have diminished his enthusiasm for Steve Canyon nor stopped him from collecting strips.

As a comic strip enthusiast, I don’t see Caniff’s practice of using an assistant or sending prints to fans to be disingenuous or deceptive. An important component to Caniff’s success was his willingness to respond to his fans’ requests and have ongoing conversations with them. They would probably understand his need to take shortcuts in order to meet his publishing deadlines.

Advertiser. At the top, Steve Canyon is printed in a quarter-page layout.

One of the offshoots of my research was that I started collecting original artwork and related items from other Caniff collectors. Through this, I gained an appreciation for Caniff’s ongoing interaction with his readers, even into his later years. The artwork he sent to the Baumans may have been similar to artwork he sent to friends and other military families who followed Steve Canyon. The important thing was that he responded. His fans valued their connection with the artist.

Jeff Singh was the first comic art collector I reached out to when I started my project. Over the years, he and I have traded a number of pieces of Caniff artwork. He is also the person who introduced me to the Comic and Fantasy Art - Amateur Press Association.

Early in 2019, I found myself between jobs with a lot of time to kill. Why not get this damn project off the back burner and finally finish it? To hell with trying to sell it, I’d write it, submit it to CFA-APA’s magazine and be done with it.

One benefit of having all this free time was that I could finally visit the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum, which I did in April. I spent two days pouring over Caniff’s correspondence and discovered several letters from Dorothy and Richard Bauman that I’d long suspected were in the library’s archives.

Through these new letters, I rediscovered what had first sparked my seven-year obsession to tell the Baumans’ story — their love for each other and how a comic strip became a testament of that love.

I did fall down a rabbit hole back in 2012 when I purchased Richard Bauman’s Steve Canyon collection, but it has proved to be a rewarding trip. First and foremost, I got to read the entire run of Steve Canyon, with many strips appearing in larger formats than you’d find in reprint editions.

As I researched my project, I traveled down many circuitous paths, uncovering fascinating tidbits about my favorite comic strip artist. I also got to meet a slew of generous people, from fellow collectors to archivists and researchers and, of course, to the Bauman family. It was a pleasant journey and a remarkable gift to an old comic book collector.

Footnotes

-

In fact, because Titan cut back its release schedule to three and then two books a year, it took until October 2017 before the final Modesty Blaise story — Zombie — was published.

-

IDW’s release schedule has slowed to about one Steve Canyon book per year. Volume 10, which is due out January 28, 2020, features stories from 1965 and 1966. At that rate, it will take IDW 11 more years to complete publishing the entire run of the series.

-

This story was originally published in the Summer 2019 edition of the Comic and Fantasy Art - Amateur Press Association magazine (CFA-APA #107).

-

The only piece of Richard Bauman’s artwork I failed to acquire was the Steve Canyon print from 1952.

-

I can confirm that there is one other complete run of Steve Canyon in existence, because I own it. In 2016, I purchased the collection from a pawn shop in Western New York. Bob Bindig, a Buffalo-area cartoonist and cartoon art archivist, assembled the collection. I was also able to purchase Bindig’s complete set of Terry and the Pirates strips, as well as scrapbooks he put together about Milton Caniff and his work.

-

While assembling research materials to write my first Bauman feature for CFA-APA, I discovered that the audio recording I had listened to in 2013 had been taken from a video interview. The full video is now available to view on the Veterans History Project’s website (https://memory.loc.gov/diglib/vhp/story/loc.natlib.afc2001001.35029/).