It's funny, I can't decide if Alejandro Jodorowsky is the quintessential man-who-needs-no-introduction or if the scope of his myriad pursuits demands some focused outline. Forgive me this compromise. A veteran of cinema, circus, music, mime, poetry, theater, tarot, and, for forty-five years, comics, the 82-year-old Chilean native remains remarkably difficult to pin down, boasting new or imminent projects in four languages. Spanish readers can soon enjoy his latest prose work, Metagenealogía (written with Marianne Costa), expanding on the "psychomagic" concept detailed at length in 2010's Inner Traditions English translation of Psychomagic: The Transformative Power of Shamanic Psychotherapy, while German art book publisher Hatje Cantz Verlag plans a 48-page facsimile extract from a 1974 notebook compiled during his preparation for a movie adaptation of Frank Herbert's Dune, the doomed project on which Jodorowsky met artist Jean "Moebius" Giraud. This relationship led Jodorowsky into French comics, his latest work of which is the second volume of Final Incal (art by José Ladrönn), a sequel to a sprawling, tarotic, Moebius-drawn sci-fi series now collected in English under one cover as The Incal Classic Collection, with its original 1980-88 colors restored after a misadventure in modernization back in the '00s.

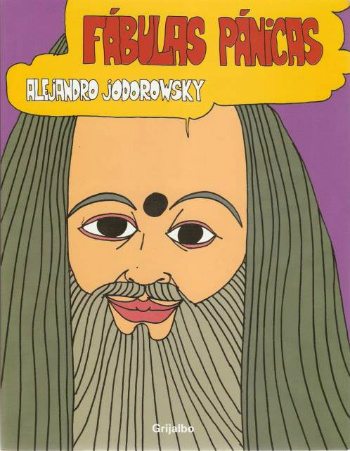

Yet that doesn't quite capture the Jodorowsky of comics. From 1967 to 1973 he wrote and drew Fabulas Panicas (collected in Spanish by Grijalbo in 2006), a weekly Mexican newspaper feature named for the Panic Movement he formed with Fernando Arrabal and Roland Topor several years earlier; it was produced in tandem with other Mexican projects -- recently showcased at his Gabinete Gráfico exhibition at the Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil in Mexico City -- including comic-book collaborations with artist Manuel Moro dating back to 1966. These works remain untranslated and set apart from English editions of Jodorowsky's French works, steeped as those are in the stop-start history of bandes dessinées localization in America - standalone albums, serials in magazines, comic-book lines, partnerships with superhero publishers, etc.

The current preference is for fat, ideally comprehensive collections of individual series, and Humanoids, Inc. -- the North American wing of enduring French publisher Les Humanoïdes Associés, which Moebius had co-founded in 1974 -- has duly completed translations of Incal spinoffs The Metabarons (art by Juan Giménez) and The Technopriests (drawn by Zoran Janjetov with digital elements by Fred Beltran), along with the (initially incompletely) Dark Horse-published Moebius collaboration Madwoman of the Sacred Heart and the multi-artist short comics compilation Alexandro Jodorowsky's Screaming Planet, its segments formerly anthologized across individual comic-book issues of Métal Hurlant back when those seemed more viable. This very day sees the release of a new chunk of material from the gunfighter series Bouncer (art by François Boucq), while the near-future promises an all-in-one edition of The Metabarons, perhaps the most comprehensive expression of Jodorowsky's fascination with family, psychology, and adventuresome iconography in comics form. Meanwhile -- and on the familial theme -- emancipated Métal Hurlant half-sibling Heavy Metal anticipates the fourth and final installment of Jodorowsky's papist mayhem opus Borgia (art by Milo Manara), while its archives hide a two-volume 1990s Georges Bess-drawn revival of Anibal 5, one of his Mexican comics from years back. Gradually, the constellation comes more into view.

What follows is a short interview, conducted by e-mail; it can't possibly cover the breadth of this life in comics, no matter how tangled my questions get. Jodorowsky, however, remains spirited and good-humored, and delightfully unwilling to tolerate windiness. I have applied only minor typographical fixes and a few hyperlinks to the text, so as to preserve the style of the artist's responses. You can be sure you'll hear from him again soon, but just as surely in another form, or another tongue - always somewhere else.

***

MCCULLOCH: I would like to start with your first experiences with comics. In Chile or France, when you were a child or a student, or composing poetry and performing in mime, did you read comics?

JODOROWSKY: I began to read comics when I was 7, in Chile they were publishing the sunday pages of american papers : Mandrake the Magician, Prince Valiant, Flash Gordon, Popeye, Tarzan, etc... When 14 years old I went crazy with Will Eisner [The] Spirit.

MCCULLOCH: Your earliest comics I know of came from Mexico, after you founded the Panic Movement with Fernando Arrabal and Roland Topor. Specifically, the earliest is Anibal 5 in 1966, with the artist Manuel Moro, with whom you subsequently did Los insoportables Borbolla. How did these publications come about, and did your work with Moro differ from your later comic collaborations?

MCCULLOCH: Your earliest comics I know of came from Mexico, after you founded the Panic Movement with Fernando Arrabal and Roland Topor. Specifically, the earliest is Anibal 5 in 1966, with the artist Manuel Moro, with whom you subsequently did Los insoportables Borbolla. How did these publications come about, and did your work with Moro differ from your later comic collaborations?

JODOROWSKY: In Mexico the comic industry was popular, childish, mexicanista. Because of my theatrical plays I had for an admirer a publication director of the Novaro editions. I convinced him to create a scifi serial. We decide to publish 12 numbers. The editors without understanding what I was doing published in the cover pictures of an actor I didn't admire, imitator of James Bond and in the back cover an idiot bimbo. I fought to change that and I obtained that in the number 6 the cover would be drawn by Moro. That was good but had a bad effect. The owner of Novaro read my comic and scandalized they abruptly end the serial. Moro was one of the drawer working as an employee not being respected as an artist. He had to draw anything they tell him to draw, for him drawing Anibal 5 was a kind of liberation.

MCCULLOCH: In '67, you also began drawing Fabulas Panicas, a Sunday comic for El Heraldo de México, concurrent with many other pursuits, such as your films Fando y Lis, El Topo and The Holy Mountain. Was there a specific quality to comics that resonated with the Panic Movement?

JODOROWSKY: The Panic Movement was kind of a joke. Topor Arrabal and I we called panic everything we did. More than a theory it was more like a brand. Anibal 5 was an artistical try not industrial. I did it for free for Novaro.

MCCULLOCH: Most of your comics have been made with other artists. Do you feel there is an intimacy to comics collaborations that is absent from film-making, or directing theater? Or, conversely, is there more give-and-take in working with only one other person?

JODOROWSKY: Yes, to make a comic it is a paradise. Evidently if you admire the drawing artist. You don't have a greedy producer on your back. And you can invent without economical limits everything you want. If you want 10000 cosmic spaceships, it doesn't cost more money than drawing a horse.

MCCULLOCH: Your first comic with Moebius was Les Yeux du Chat in '78; it was a giveaway book for Les Humanoïdes Associés, which Moebius had co-founded a few years prior. You've mentioned before that you raised the idea of collaborating a comic to Moebius — were you following the developments in French comics toward a more surreal, subconscious-borne type of fantasy in Métal Hurlant?

JODOROWSKY: Yes I collaborate in the foundation of Metal Hurlant with my ideas and revolutionary texts like "The sexual life of Superman" where I was describing the Superman ejaculations so strong that the sperm going through the woman vagina, the whole body, the head and went away exploding the head and destroying a skyscraper.

MCCULLOCH: You have since worked with many artists on many different stories. Do you have a firm idea about how a story is going to proceed before an artist is drawing it, or do stories tend to develop more in the process of collaboration? How closely do you work with artists while they are preparing the artwork?

JODOROWSKY: I have an idea and while I am writing, new ideas are coming. I call by phone the artist daily.

MCCULLOCH: The Incal is an interesting series for readers in the United States right now, because it is the origin of many of the other series of yours being published, such as The Metabarons and The Technopriests. Have you found your approach to this shared universe changing as you revisit it over the years, accumulating detail and history?

JODOROWSKY: It is like a tree, it never stops growing.

MCCULLOCH: There are also several direct continuations of The Incal, such as Avant l'Incal, which Zoran Janjetov initially drew in a style close to Moebius' designs. Do you feel that there's a necessity to keep these stories visually close to Moebius' designs, in that he was the originating artist? Does this bear on your collaboration with Ladrönn in Final Incal?

JODOROWSKY: Yes, it is necessary to keep this story close from Moebius drawings but without copying it and making it richer.

MCCULLOCH: Both The Incal and Avant l'Incal exist in different forms, at one point with newer, considerably different colors introduced to Moebius' and Janjetov's drawings. Were you consulted regarding these visual alterations? Do you feel a comic is "finished" when it is published?

JODOROWSKY: With the 3 d fashion the Humanoids editor trying to seduce the young audience changed the comic colors. I didn't like that. But comics are an industrial art like movies and it needs to sell its products. But time gave me right. The audience prefers the original colors.

MCCULLOCH: Relatedly, I've noticed that many of your comics are attentive to individual albums as unique pieces of storytelling. For example, each chapter of The Metabarons is structured as Tonto starting and finishing a story. The same is true with Albino's narrations in The Technopriests. Even in Madwoman of the Sacred Heart, there is a distinct shift in Moebius' drawings between chapters, as time passes. Do you feel individual comics albums, even if only a chapter in a larger story, should be experienced alone, and are readers in the United States missing some of the enjoyment in only reading these series as big omnibus books?

JODOROWSKY: This question is too long and annoying for me. I stop to fart.

MCCULLOCH: When Métal Hurlant was revived in the '00s, you wrote a series of short stories on the theme of a planet's fragment passing by various worlds (later collected into Alexandro Jodorowsky's Screaming Planet). I was struck when the editors of Métal Hurlant mentioned that for many of the stories you had not seen samples of the artists' works before writing the scripts, which is quite different from how you usually collaborate with artists. How did these stories come about? Do you have any favorites among the shorter Métal Hurlant pieces?

JODOROWSKY: The editor was telling me the qualities and limits of the artists. For example, there was one that was drawing good the characters but not the cities. I invented a story the takes place in a desert. Another didn't knew how to express emotions, I invented a robot world without any human. I took it as a challenge, a game.

MCCULLOCH: I greatly enjoyed the metaphor running through The Technopriests of video games as both creative expression perverted by industrial demands and the concern of technological developments standing in the place of human relationships. Has navigating the industry of comics changed with the passage of time and technological changes?

JODOROWSKY: Everything is changing, not only comics, even the brain of human beings is changing.

MCCULLOCH: Once, when asked if you were a magician of cinema, you replied that you had made very few films, and that film-making is like karate, where you must punch and punch and punch to achieve magic. Do you feel you are a magician of comics?

JODOROWSKY: I feel myself like a genius and a sacred whore.

MCCULLOCH: Do you read many new comics, and are there any you've particularly enjoyed?

JODOROWSKY: Prince Valiant, graphic novels of Will Eisner, [Katsuhiro] Otomo's Akira.

MCCULLOCH: Finally, is there a message you would like to give to artists making comics today?

JODOROWSKY: Kill Superheroes !!! Tell your own dreams.