In May 2014, I interviewed Daniel Clowes for the fourth issue of the excellent bilingual French journal Collection Revue. It was an interesting moment to catch up with Clowes. His last new book, Wilson, had been published in 2010. Since then, Clowes had been the subject of several retrospective projects. A career-spanning exhibit of his work, Modern Cartoonist: The Art of Daniel Clowes, had opened at the Oakland Museum of California before traveling to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, and it was then on view at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio. The Art of Daniel Clowes: Modern Cartoonist, a companion monograph, was edited by the late Alvin Buenaventura and published by Abrams in 2012. In 2013, critic Ken Parille edited The Daniel Clowes Reader, a collection of works by Clowes accompanied by a range of companion texts (Parille and Isaac Cates had edited a volume of interviews with Clowes three years earlier).

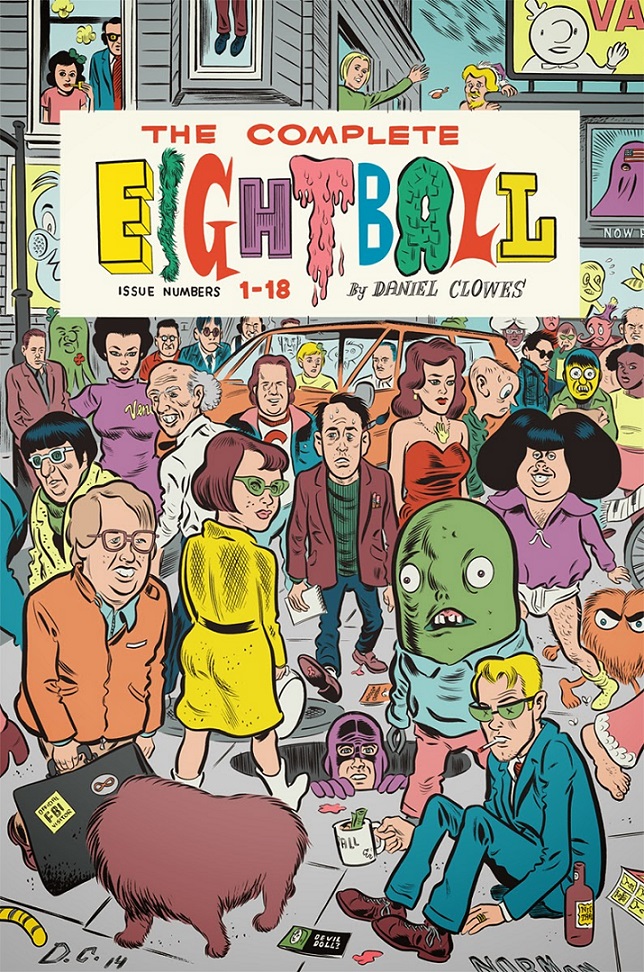

At that moment, Clowes was producing new artwork for the upcoming Complete Eightball boxed set (another retrospective project) while simultaneously working on a new graphic novel, about which nothing was publicly known. Patience, referred to obliquely in the interview, was published in 2016, two years later. At the time of this interview, Clowes was both looking at his past and looking towards the future. We had a fun and interesting conversation that I was proud to share with readers of Collection Revue.

Now that the journal in which this originally appeared is out of print, it seemed worth making this interview available again, especially for those readers outside of France who likely wouldn’t have had a chance to see it. This conversation was edited for word count and clarity and appears here as I submitted it to Collection Revue in 2014.

BILL KARTALOPOULOS: You currently have a large, retrospective exhibit touring the U.S. called Modern Cartoonist. This has been in Oakland and Chicago, and now it’s in Columbus, right?

DANIEL CLOWES: Yeah, and I think that’s it.

It’s not coming anywhere to the East Coast?

Originally, our idea was to travel across the country, and it was going to go to the Corcoran in D.C. I’m not so up on all the intrigue in the museum world, but I guess they had some huge funding deficit, and they had to fire their board and hire some new president and all that, and in that whole shuffle they cancelled all outside shows. And I heard all this stuff about the board, and they were not so excited about the idea of putting comics in there anyway. And so, when they later came back and wanted to try to talk to us again about getting it back there, I just had lost interest after hearing all that. When the exhibit started, it seemed like this abstract thing, and I didn’t have any sense of how it would feel. But now I want all of this stuff back. [Laughs] I keep seeing it hundreds of miles away from my house, and I’m like, “I want my artwork back in my room.” I don’t know. It feels weird. It’s like having children away at camp for two years or something.

The exhibit is called Modern Cartoonist, and that’s also the name of the art book and catalog that Alvin Buenaventura edited to accompany it. It takes its name from a pamphlet that was in Eightball #18 in 1997. I actually re-read that last night for the first time in many years. Have you re-read that?

I’ve never read it since I published it. I’ve definitely never even read the actual pamphlet. I only read it as I was writing it, so I couldn’t even tell you what it says. I have almost no idea. The idea behind it wasn’t really the content as much as having a crazy pamphlet out there. I like the idea of the kind of thing that you’d just leave on a bus seat or in an airport or something, that has this crazy rant that no one else really cares about, that’s about a subject that the writer seems to have way too much interest in and doesn’t quite know how to express to the average person out there. And that was the whole reason for doing it. And then I just filled it up with whatever was going through my head at the time. [Laughs] I always felt like people took the content a little too much as gospel. And, of course, who could blame them, since it was presented that way? But it certainly wasn’t intended as “my one pronouncement about comics.”

It’s actually a very sharp document. There’s one aspect to it that actually seems very prescient — even though it’s in some ways obviously very parodistic of a messianic death cult mentality — which is this notion that every 15 years, comics reaches a new phase. In ’38 you have Action Comics, and in ’53 you have the height of EC, and in ’68 is Zap, and ’83 is the beginning of alternative comics. And you wrote this in ’97, just at the end of another one of these cycles. And actually, you weren’t too far off because in the year 2000 I think a lot of things did change.

Yeah, I guess. [Laughs] I sort of felt like it was a more even flow from the mid ’80s up through now, really. You can sort of just see the through-line of all that. Whereas all the other movements I was talking about, everything sort of stopped and then re-began. You know, the undergrounds stopped. And then my generation kind of began out of nothing. There was just nothing there. And the undergrounds certainly came out of nothing, after EC and MAD and all that had died. But it seems since that it’s just been this river that’s branching out into all these different sub-categories.

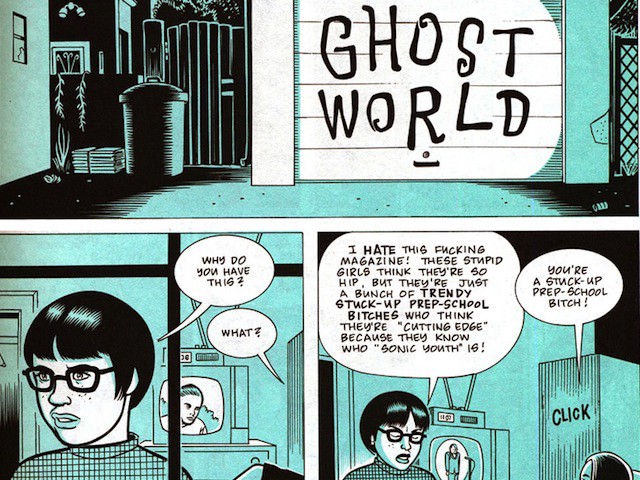

I taught Ghost World in my classes only once, and I thought, “Oh, this is perfect. These young art students in New York are going to fall in love with this book.” And some of them did. There was also some surprising feedback from some of the students who thought that the characters were just “too negative.”

Yeah. [Laughs] I mean, that was always sort of the reaction to it. I think maybe people are a little more shocked by that kind of negativity now. It was more just part of the cultural fabric at the time it was created, and it didn’t seem so shocking. Now, I think people aren’t used to that kind of negativity or are not allowed to be negative like that —in grade school certainly — anymore.

But I actually always thought that the success of both the book and the movie came from the fact that it’s somewhat nebulous as to what my opinion is of the two girls. And so, you can see it either as I’m in favor of them, or that I at least have some affection and sympathy for them, or you can see it as an indictment of them. Which is certainly not my intention, but it’s not spelled out enough that either way seems like the definitive way to see it. So, I think half the people who respond to the book are assuming that I’m being positive, and the other half are assuming that I’m being negative. And both of those are ways in which the book can be enjoyable to those particular audiences. And so therefore, it’s not just for this kind of tiny niche of people who are in support of that worldview. It’s for a much larger audience, kind of unintentionally.

And then there’s an even younger cohort, it seems, this Rookie Magazine generation of people who almost romanticize things like Sassy Magazine and maybe are more ready for the negativity than their older siblings, or people who are half a generation ahead of them.

There’s a fashion element to it, too, where I was just sort of making up the way they dressed. It was sort of vaguely based on the way I knew some girls in art school dressed, but it wasn’t really anything specific. I wasn’t trying to depict a type of trend of the day. And so therefore, there are all of these fashion designers who refer to Ghost World as this sort of “style” of clothing, and there’s something about that kind of simplification in comics that lends itself to people seeing that kind of thing in it.

I don’t know if you’ve seen any of these websites on Tumblr, but there have been blogs on Tumblr devoted to your work. And the first one that I saw was called fuckyeahdanielclowes.tumblr.com. Have you seen any of these?

Yeah, yeah. Alvin sends me anything interesting. You know, whenever somebody has a really elaborate tattoo, or does a needlepoint of Enid or whatever, Alvin alerts me of everything.

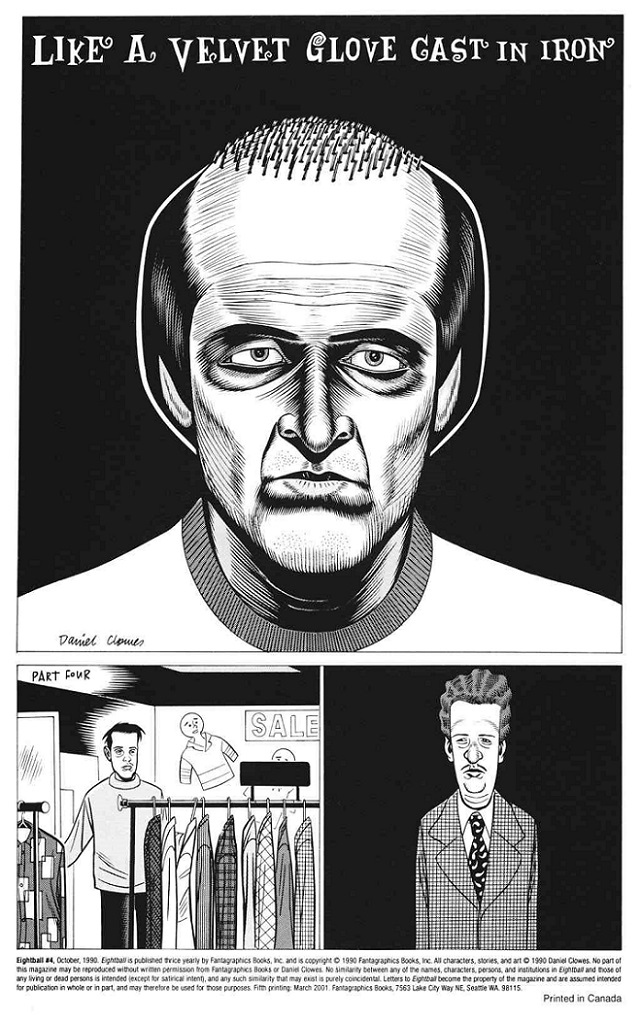

One of the things that took me a little off guard when I first started seeing these blogs on Tumblr was how frequently they selected images from the earlier issues of Eightball, the more satirical issues, images that had a more grotesque style. Why do you think these users would be attracted to those images specifically?

I think they’re certainly more potent as single images than maybe something from Wilson or Ice Haven or The Death-Ray. Those are much more intended to work as comic strips, as pages, as narratives. A lot of that early Eightball stuff is really just about “that” particular panel. A lot of the Velvet Glove story is coming up with these certain indelible, striking images and then finding ways to get to them. And so, it tends to be picking and choosing those things. And it’s somewhat flattering, but you don’t want this stuff to be read out of context like that, to be reduced to some clip art images on Tumblr. It’s not at all what I intended, and it feels beyond my control. It feels strange that it’s OK to do that, I guess. [Laughs] That’s the way it is. There’s nothing you can do about it. I’m not exactly comfortable with it.

I guess you’ve probably been looking at that work a lot more because of the exhibit than you might have before. How does that older work, stylistically, look to you now?

You know, I’ve found my peace with it. It used to be I’d look at it, and I’d just see the struggle and the mistakes. Especially in those very early issues of Eightball and Lloyd Llewellyn. I can almost feel the tenseness in my hand, where I was struggling so hard to achieve something that I just wasn’t capable of, a certain kind of old-fashioned, fluid ink line. But now, I see that the work, by showing that so clearly, has a certain validity to who I was at that time. I always think of style as something that’s the distance between what you want something to look like, and what your hand and brain make it look like unintentionally. And there’s quite a gap there, and there’s some interesting stuff in that gap.

I have been looking at it a lot because I’m doing The Complete Eightball right now, and I’m doing all these new images for it, for the covers and the slipcase and all that. And I’m trying to draw all these old characters for the first time since I originally drew them, some of them 20 or more years ago. And it’s funny, some of the ones that have this kind of real angular stiffness, I literally can’t draw it as stiffly as they originally looked, even though I’m trying to. I’m trying to recapture that feeling, and it’s just impossible. I’m much more relaxed and confident, and you can’t, like, summon a lack of confidence like that. I’ve been really trying to, like, listen to the same kind of music I used to listen to and really get in the same “headspace” as they would say, but it’s very difficult.

Do you still use the same essential tools that you were using then?

Yeah, yeah. I still have the same little pen holder, the same lead pointer and all that stuff. It hasn’t changed at all.

So, it’s completely the brain and the hand that’s the difference.

Yeah. It’s a certain muscle memory, where your hand all of a sudden knows how to do things that back in 1989 I was struggling to make it do, and now it does it without thinking.

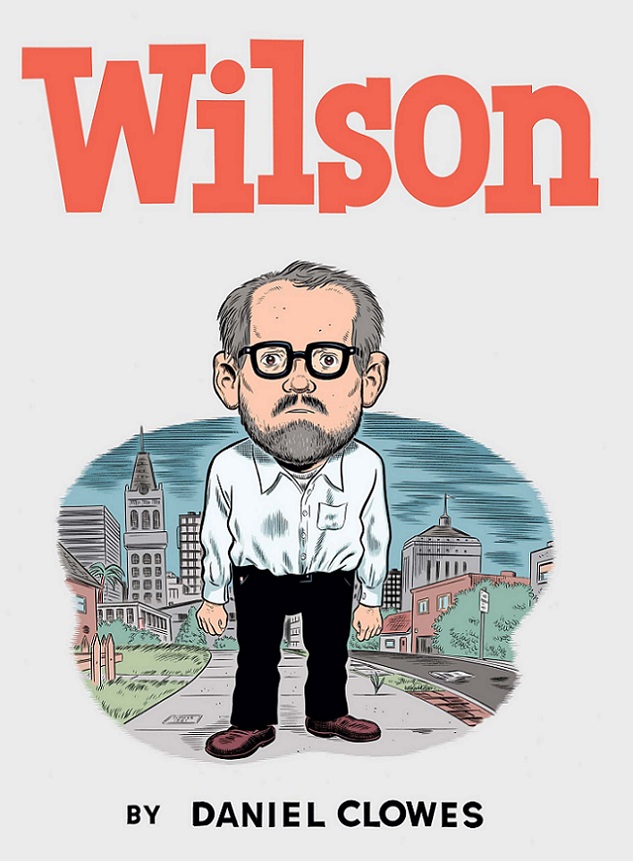

You’ve had a lot of books out over the last several years. Some of them have been new editions of older work, like Mister Wonderful and The Death-Ray. The last long book of new work was Wilson, which is a few years old now. It seems to have been warmly received, but in some of the reviews that I read there was a feeling of people not knowing exactly how to talk about it, or how to analyze it, not knowing entirely what to make of it. It’s an unusual book. I’m tempted to see Wilson in some ways as an echo of earlier comics, like “I Hate You Deeply,” with that unfiltered ranting style, even though there’s so much about it that’s completely different. But did you conceive of the character in any way as an opportunity to write humorously or to write humorous dialogue?

That’s how it began. I was really just trying to write little sketchbook, stick figure strips to amuse myself. And this character just kind of emerged. He was just sort of an id version of myself originally, and then he just became real. And that’s what you sort of pray for with your characters, that you can have somebody that you don’t have to move around like a chess piece. You can just let them do what they would do, and it’ll be interesting. And it happens every once in a while, and he was one of those. I mean, that book could have been 800 pages long. I could have just kept going forever. I felt like if I was going to do a daily strip, I had found the guy that could carry that for 25 years. He was my “Funky Winkerbean” or whatever. [Laughs] But I also liked the idea of eliminating all the stuff in the book that I didn’t find had a charge to it, or was either funny or had a certain pathos, or something that felt valid in and of itself as a strip … I just took out of the book. Some of them I drew, and some of them I never got around to drawing, but it just felt right to have it as spare as possible in that way. I don’t know. Of all my books, that’s the one I’m proudest of, in a way.

It’s a very fascinating and, I think, complex book. It reminds me of a magic trick: Magicians have a “stage patter,” where they talk to distract you from what it is that they’re actually doing.

That’s very good, yeah.

Wilson’s both passive and active at the same time, but he’s constantly talking, and it smooths over just how crazy the actual narrative is.

[Laughs] Yeah. Yeah, I think that’s right. And yet it’s sort of logical. If you tell somebody the story, it seems like, “Oh, that’s just the plot of a TV episode” or something. “Man reconnects with his family and goes on an adventure.” So, it’s very simple in a way. When I meet somebody and they ask, “Oh, what’s Wilson about?” … I always find myself unable to say without ruining it. It just seems so wrong the way you’d describe it: “He’s a misanthropic fellow who is looking for connection.” It just seems like, “Oh, it’s a horrible Paul Giamatti movie” or something. It’s very hard to describe, which I guess is good. Because if you can describe it too carefully, that’s usually a sign you did something wrong.

One of the things that I think is unique about Wilson is that the character is not monologuing in an abstract way. Characters like Little Lulu and Barnaby talk to themselves in old comic books and comic strips, but it’s not necessarily implied that they’re literally speaking all the time. But Wilson is actually constantly talking in a way that might be pathological, but it is normalized because characters in comics do that.

Yeah. To me, that was just inherently funny that you could do that in a comic, and it seems OK. If you really were to get an actor and film the 72 pages of Wilson as is, it would seem completely insane, just a guy wandering around talking to himself. I’ve actually written a movie script for Wilson, and you can’t really do that in a movie. It just doesn’t quite work. So, a lot of the time he’s just talking to his dog, where he’s sort of deflecting the monologue onto pretending he’s talking to his dog, which seems slightly more acceptable. But it was very difficult to try to capture that feeling of insanity without making him seem like a street person.

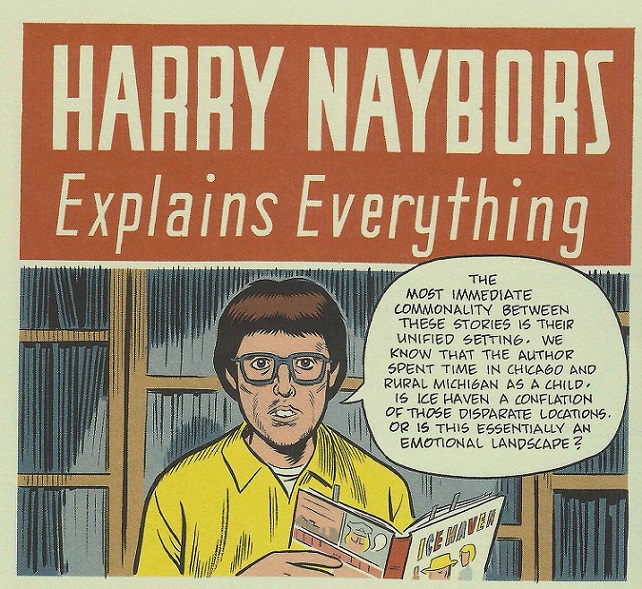

You have this Harry Naybors character who theorizes about comics in Ice Haven. He says some smart things, and people do take it as a signal from you about how your comics are working sometimes. Harry Naybors, your character, talks about private self-definition that’s communicated through text versus objective reality that’s communicated through images. And so much of your work seems to be about characters who are unreliable narrators of their own lives. They unintentionally reveal themselves through what we see about them, and when we understand how they’re lying, the lies become very telling. Do you see a connection between this capacity for self-delusion and storytelling or creativity the way that you practice it?

To me, it seems to be something that your brain almost looks for in comics, whether it’s intended or not. There’s something about that oddness of being inside a character’s head, the way you would be in a first person work of fiction, but also being outside that character. Unless you’re doing a comic like that one I did years ago called “The Stroll,” where you’re seeing just what the character sees through his eyes and not objectively. But I don’t know. It’s always struck me as something I almost can’t control, writing these characters internally and then kind of forcing myself to see what the reality is externally. It seems like two very different parts of the brain.

Wilson is so unfiltered that he kind of internalizes some of these tensions. In one page he might go from self-justification to authentic despair to over-performative despair that’s starting to seem fake again. Because he’s unfiltered, do you think that’s a sort of accurate register of the way people’s brains work?

I think so. I think sort of the beauty of Wilson and what makes you, I would hope, by the end feel some empathy for him is that he is trying. He’s got sort of noble goals to connect with humanity on a deeper level than many will try to connect with. And so, I would hope it’s forgiven that he’s kind of veering from all these different uncomfortable states. He’s very much like a lot of people I know who are kind of unable to communicate on a sincere level even though that’s their greatest wish. It’s just kind of beyond their grasp.

I want to ask you about another character from a relatively recent shorter story who’s also this type of unreliable miscommunicator: Justin Damiano, from the short story that was in the Zadie Smith collection. I think one of the differences between Justin as a character and most of the residents of Ice Haven, for example, or Wilson, is that he puts a product out into the world. He puts a communicative product out there for a bigger audience: His film criticism, which he presents as some kind of authentic critical response to film, but which, the way you depict it, carries the burden of all of his problems and frustrations. Do you think that any attempt at authentic self-representation, whether it’s criticism or memoir or something like that, is doomed to fail because it’s so informed by all these things that you can’t know about?

I don’t know what failure means, necessarily. I had to get pretty serious heart surgery in, I think, 2006, and that story was the very last thing I did before I knew I was going to have, like, a year of no work, at best. And that might have been the very last thing I ever did. So, I treated it kind of like that, as: “This is how it feels to produce comics or art, or to release things into the world.” And I had just come off an experience of doing press junkets and things for books and for movies and having this experience of being on the other side of that table from these critics, and a lot of guys like Justin who are these sorts of young, self-styled internet critics. I wanted to sort of see how it felt to be on that side, and the more I thought about it, the more it felt like doing the same thing that I was doing, just in a different form.

You don’t really cast Justin in a real great light, but it sounds like you’re saying your work is similarly loaded with all of your life experiences …

And everybody’s is. And I certainly know it’s somewhat about a younger version of myself, maybe a little more explicitly, where everything I did was sort of based on minor slights from people who I would then do an entire graphic novel just sort of built around that emotion. All these little things that get you moving to create art are very rarely anything noble. It’s all little pangs of ego, and things like that.

Do you think it’s in some ways more authentic to do it through fiction, where you’re acknowledging there’s something both real and unreal about it, rather than an autobiography or criticism or something that’s ostensibly not manipulated in that way?

Yeah. I think it’s the only way you can be really honest and really go as far as you want. If you’re doing it as autobiography, you’d have to worry about libel suits and things like that. [Laughs] And there are people you might want to depict because they’re interesting characters, but you don’t want to humiliate your friends or family. I just think fiction is a much better way to explore all that stuff. I’ve never really done straight autobiography, but I feel like I’d be so inhibited, and I never feel that way doing fiction.

You had mentioned before how you’re doing this new art for the Eightball boxed set, and how you can’t exactly recapture that older drawing style. Wilson, of course, is drawn in a lot of different drawing styles. Some of them are like a heightened dramatic realism closer to David Boring, and some of it’s much more cartoony. And there’s so much visual diversity throughout your work, but it seems like the biggest development in the last several years has been a move to incorporate a more Charles Schulz-like, simplified, cartooning style that has a minimal amount of detail while still maintaining a broad capacity for expression. Given the diversity of visual styles in your recent work, do you feel like you have a “neutral” or “baseline” style these days, a way that you “normally” draw?

Yeah, that’s a really interesting question because I’ve been working on a book for the last couple of years that’s somewhat in the same style throughout, and it’s now starting to feel like that’s my baseline style. But it’s really nothing like anything else I’ve done. It’s a much more kind of detailed, image-based style than I’ve done in many, many years. It sort of depends on what I’m working on. I can quickly shift into thinking I am a daily strip-style cartoonist, like a Charles Schulz-type cartoonist. If I do four or five pages like that in a row, it feels like that’s all I’ve ever done. But I don’t know. I’m too easily swayed by any influences. If I look at something that has this kind of density and texture to it, I immediately want to do something like that. If I look then at Barnaby again, I think, “What’s the point of all these extra lines? Why not just pare it down to something that looks like it was made by a machine?” It’s always a battle to keep myself drawing in a consistent way when I’m doing something that requires it.

Was there any specific influence that prompted you to try and develop that more simplified style over your last few books?

I always have this notion that simpler is better in comics. I wanted a certain number of the things in Wilson or in Ice Haven to be so readable that you couldn’t not read them. I wanted there to be certain elements to those books that made them so that somebody could pick up the book and flip to one of those pages and just, all of a sudden, be drawn in to it because it’s almost impossible to not read, the way that Peanuts or Nancy or something like that is. I find that very appealing. When I open up a graphic novel, and you see these big, dense word balloons, and you think, “Man, I do not want to read that.” This would really have to be written by William Faulkner to get me to read that, and I know it’s not going to reward that. So, I don’t want to ever have that feeling unless I’ve earned the reader’s trust by having enough strips that aren’t filled with that kind of density.

I want to ask you a couple of questions about the exhibit that you mentioned before. How did the exhibit come about?

I think it was eight years ago that I was approached by this woman called Susan Miller who was a local curator and used to run a non-profit art space in San Francisco called New Langdon Arts. I’d just known her from the art world here in San Francisco over the years. And she said, “I think it would be great if you had a full career retrospective at a museum around here.” And, I thought, “Yeah, that would be great. Good luck!” [Laughs] Good luck with that. And she said, “No. I’m really going to try to put something together.” It just seemed like it was one of those things that was not going to happen. But there were a lot of parts to it that were interesting to me, mainly the idea of cataloging what I had in my drawers. I just had all of my artwork and sketches and everything shoved in a flat file and not organized, and I’d kind of lost track of what I had. And she was like, “I’m going to organize everything,” and she went through all of my sketchbooks and wrote down exactly what I had. So, it was useful in that way.

And then it took years and years and years, and finally she put together this really impressive show after the Oakland Museum of California agreed to take it, and then the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. But it was never something I was fully engaged with. If you were in school, and you were a painter and wanted to be a gallery artist, that would be something that would always be in the back of your mind, I’m guessing, to have a show in a museum. But that wasn’t anything that ever once occurred to me. So, in a certain way I felt guilty because I felt like there were a lot of artists who deserved to have something like that [Laughs] and who it would have probably meant a lot more to. But it’s a very surreal experience, certainly, to walk into a museum and see a room full of your work.

So, you weren’t actively involved with the development of the show. It sounds like you took a fairly hands-off approach.

I just don’t have any sense of how things are going to look in a space or in 3D. My brain only works at a very close range. When I step away from my artwork more than seven or eight feet, it becomes something else. It becomes these abstract shapes that don’t quite necessarily make sense as images, and that’s not my concern. My concern is how they feel when they’re at the right size, sitting on your lap while you’re reading. And that’s a very different thing than having them work as images on a wall. So, I tried to stay out of it as much as possible. And in fact, every bit of advice that I gave, once I saw the show hung for the first time, had they listened to a word I said it would have been disastrous because every single thing I said would have just been ruinous to the show.

Was there anything about the presentation of the work that surprised you?

To see the originals from that vantage was surprising. Because I’m looking at them with a very powerful fluorescent light and my reading glasses, and I’m two feet away hunched over the drawing board, and so I’m seeing all the mistakes, all the places where the ink is sort of washed out, and where I’m pasting things on. Everything looks very rough and kind of imperfect. And then you see it on the wall and all that stuff kind of disappears, and everything looks kind of frighteningly perfect. I almost felt like I was mentally ill or something, [Laughs] that I had not been able to see how sort of careful and meticulous a lot of things were, that I had thought of as being sloppy and kind of slapdash looking.

Do you think the exhibition format tends to over-represent or under-represent any aspect of your work? Or comics in general?

My concern was to have enough strips on the wall that you could read. So, anything that I had that was a single-page strip that worked all in the one page, I tried to get on the wall. And I tried to have sequences of stuff, and I tried to have a lot of the Wilson strips and things like that. Because I wanted people to actually stand in front of them and read at least bits and pieces with the hope that they would then maybe want to engage with the book itself.

I wasn’t sure how I would feel about it, but by the end I really felt like it was a valid experience because there were a number of people who had never heard of me who would come to the show and see the work and connect with something they saw. Whether it was an image, or a page, or even just the typography, or something. They would then buy the books, and then I would hear from them: “Oh, I had never heard of you, but I saw your show, and I bought your books, and now I’ve connected with all this stuff.” And then there were the other people who already knew my work, and they already had an intimate relationship with some of these pages or panels, and then they would go to the show and there’s the page itself, and they can kind of see all of the mistakes and sense that it was drawn by an artist. Whereas when you’re looking at comics printed on a page, it’s often very hard to think that it was done by a human being, or if you’re not aware of how comics are created, you just don’t even understand how the pages are made.

And so, there were two different kinds of responses among many, I guess, that were interesting to me. And I got to see a lot of that.

You had mentioned that there was some discussion at one of the potential venues for the exhibit about, “Are we interested in having a comics show? Is this appropriate for our venue?” And other institutions like the ones you’ve shown in — and places that have hosted exhibits of work by Art Spiegelman and Chris Ware and so on — have engaged this material to some extent. It almost feels like comics’ engagement to the art world is almost where comics’ engagement with the literary publishing world was about 15 years ago. Do you see any kind of future in this, or is this something that you think young artists should keep in mind?

Those are two examples of the same thing, where you always feel like both the art world and the literary world embrace comics up to a point, where they feel sort of safely superior to them. But then, in some aspects of publishing, when comics start outselling actual prose work, there tends to be this kind of bristling against them. I don’t know.

I feel like comics needs its own thing. I don’t mean necessarily its own museums or its own publishers, but it feels weird to always be kind of piggybacking on these established forms. It needs its own space somehow, and I’m not even sure what I mean by that. I feel like I, in particular, need to really just devote myself to comics much more than I have in the past years. I feel like I need to really keep that as my one focus in my career from now. There’s lots of little other things that you can do besides comics, but I feel like that’s the one that I need to follow through on from now on.