I was fortunate enough recently to get my hands on Gouffre, the new giant-sized anthology by the the French Lagon Revue. After reading page after page of artists boldly experimenting with form, printing, and difficult visual concepts (and there are a few doozies), Jason Murphy’s story "The Character" stood out.

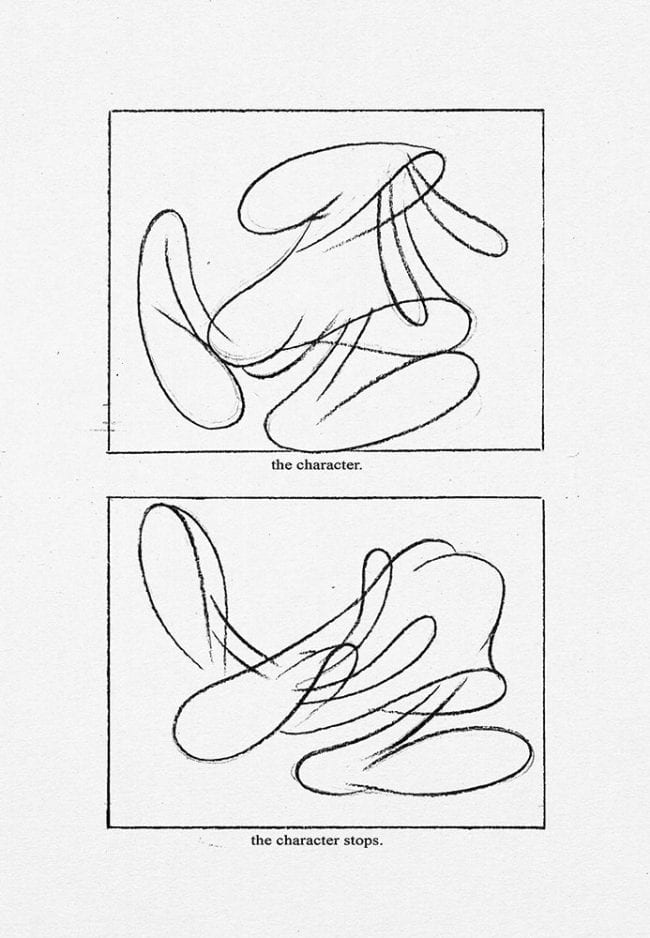

Murphy can make his panels look like he somehow captures the confusing millisecond between two shuffling animation cels. They can read lightning fast with a line that swims and zips around the page, but can also leave you feeling inexplicably strange because there is a distinct lack of traditional gratification that we’ve been trained to desire. Murphy plays with classic cartooning, and in a sense, Vaudevillian tropes, but in his comics, a rolling pin to the head can cause emotional wreckage. Someone can take a pratfall and never recover. Absurdity is both the means and the end. We talked about his evolving style, childhood symbolism, and his new short story "The Character".

RJ CASEY: First of all, how did you get involved with Gouffre and the Lagon Revue crew?

JASON MURPHY: I had a book published by the French publisher Papier Gaché a few years back. They went on to create the Lagon anthology, so they were already aware of my work. I had been cataloging these strips on Tumblr and Instagram called "The Character". Something about the strip must have resonated with them. They asked me to participate, and I was thrilled. It’s a very thoughtful and beautiful book.

"The Character" may be your most abstract story in terms of your line and character design, but I think it also might be your most approachable to someone who is new to your work. Are you concerned with accessibility?

No, not at all. I like that it’s accessible, but that wasn’t a conscious decision. My earlier work tends to be pretty cryptic, so much so that even I can find it disorienting. With "The Character", I really wanted to meld this very expressive way of drawing with a very cold style of writing. Almost like when you turn on the hearing-impaired option on a film and this very dry narration of what the characters are doing plays at the bottom. I accidentally watched an entire episode of a TV show with that turned on one time and I thought it was intentional. I actually really liked it! I think the strip is accessible because it’s so mundane and bourgeois. They are split-second moments of a small man’s working-class life, drawn and captioned. The act of making them felt quite absurd to me, which made it fun, and funny.

Wait, why is "The Character" bourgeois?

I don’t mean it in a negative way. I guess it’s because he has roaches in his house, he takes the bus, and is prone to domestic accidents. I can relate to this type of character. There’s a lot of me in there. Many of the panel captions are based on personal accounts.

Circling back to your earlier work — there is a distinct shift in style here. Your newer work heavily features swooping, circling lines, where your older work was a bit more traditional and less kinetic. Was that a choice or simply artistic progression?

It was a choice at first. I was working on a series of comics called "Juvinitive" in which the linework was very dense and stagnant. I had been using this line for a while and I decided to try something new. I swapped out my calligraphy pen for a hard, lead black pencil and I discovered that I really enjoyed the smooth kinetic way the lead moved across the paper. I became heavily influenced by classic cartoon model sheets. I made a series of drawings called “Model Sheet Drawings” that were based on the two main characters from my Me Nut Nut Nut comics series. I have found that if I ever get tired of the way I draw, I can just change tools. It forces me to adapt.

When you begin to adapt, or even start a new story, how much is thought out beforehand? Do you have end goals — themes or narrative beats you want to hit before you start? Or is a lot of it improvised?

It’s mostly improvised, almost to the point of a stream of consciousness exercise. In the case of "The Character", I made the first drawing with absolutely no forethought and I immediately felt connected to it. So, I began to draw him over and over. Then the idea of a narrator seemed appropriate. I would picture it as a deadpan performance on a stage and it made me laugh, so I kept at the story until 36 pages were there.

But The Character has no real name and no face. What did you connect with?

It’s difficult to say. It resonated with me emotionally somehow. I hadn’t drawn a character this expressive up until that point. I’m sure there’s an allegorical connection in those floppy Odie ears which represents childhood.

Is The Character a child?

No, but I feel like I was connecting with the design because of some of those childhood cartoon emblems like the Odie ears, the Mickey feet, and the Dopey butt. His design is a symbol of my childhood, but much of his story is based on my present reality. Does that make sense?

Sure. Was it easy for your kids to connect with it then? Do they read your work?

They do enjoy it, and they are very supportive. They’re both seven, so they are at a great age for making art. I probably get more inspiration from them than they do from me. I feel like they connected with my work more when they were three or four though. Much of my narrative work is silent, so I would flip through the pages with them and we would make up sound effects together.

You feel like they’ve aged out of it somehow?

[Laughter] Yes, they are much too sophisticated for it now. Three to four is my wheelhouse. I don’t know, they like it. They just don’t connect with it the way they did at a younger age. They’re making their own work now.

What does it look like?

They each have their own individual approach. My daughter can be quite pensive when she draws. She is very detail-oriented and she is beginning to use some fundamentals, like directional lighting. My son is really into creating these sort of foul, humorous characters. I guess I’ve rubbed off on him in that way. The aesthetic in my daughter’s work is closer to my wife’s. She is an artist as well, and very meticulous.

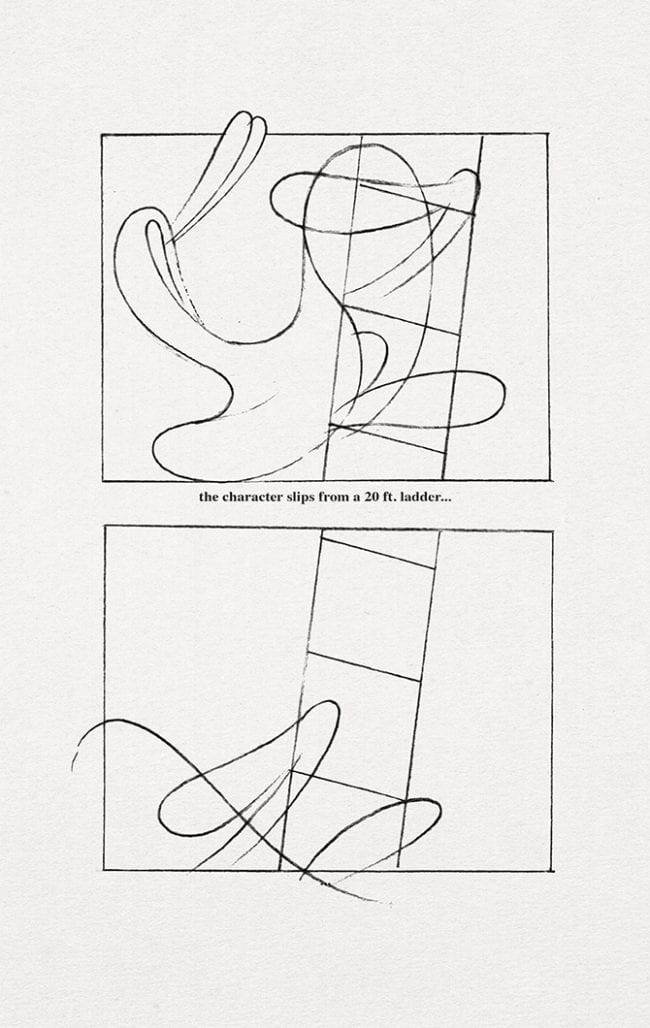

Shifting gears a bit, I wanted to ask about the setting in your comics. Do you think about the space and surroundings when you draw? "The Character" seems to be set in a vacuum, with the exception of the ladder about halfway through.

This is the first comic I’ve made without any sort of suggestion of a background. I do feel like I tend to set my comics in very rudimentary settings, as if it were a play being put on by some sort of youth group. Some of that comes from being practical with how I use my time, but also, I like the idea of treating each panel like a little diorama, with interchangeable figures and set pieces. In the past, I have composited pages in Photoshop where each element in a panel is on its own layer, so I can literally move furniture around.

I had this real-deal deathly fear of ladders growing up, and to be honest, still do, so that fall struck some emotional chord with me. The Character’s actions seem darker or sadder after he gets injured. I’m probably just projecting…

Ladders are silent killers! I didn’t intentionally take things to a darker place. It just went that way based on what was on my mind at the time. I’m glad it struck a chord. That’s all I can really ask for as an artist. For someone to connect with your work on any type of emotional level is a good thing.

When we were setting up this interview, you said that someone could “read The Character in any order and it wouldn’t matter.” I know you were kidding, but is there some truth to that? Is that how you approach narrative?

For this particular project I did, even though there are a few pages that do construct a brief narrative. The Character falls from a ladder and suffers an injury, there’s also a section in which he does a little celebratory dance. Narrative has always been a challenge for me. I’m impatient. I enjoy creating moments. Paintings are moments. Paintings can also tell stories. My comics are moments linked together to tell a story. Each panel is a response to the previous panel and that goes on until I feel contented.

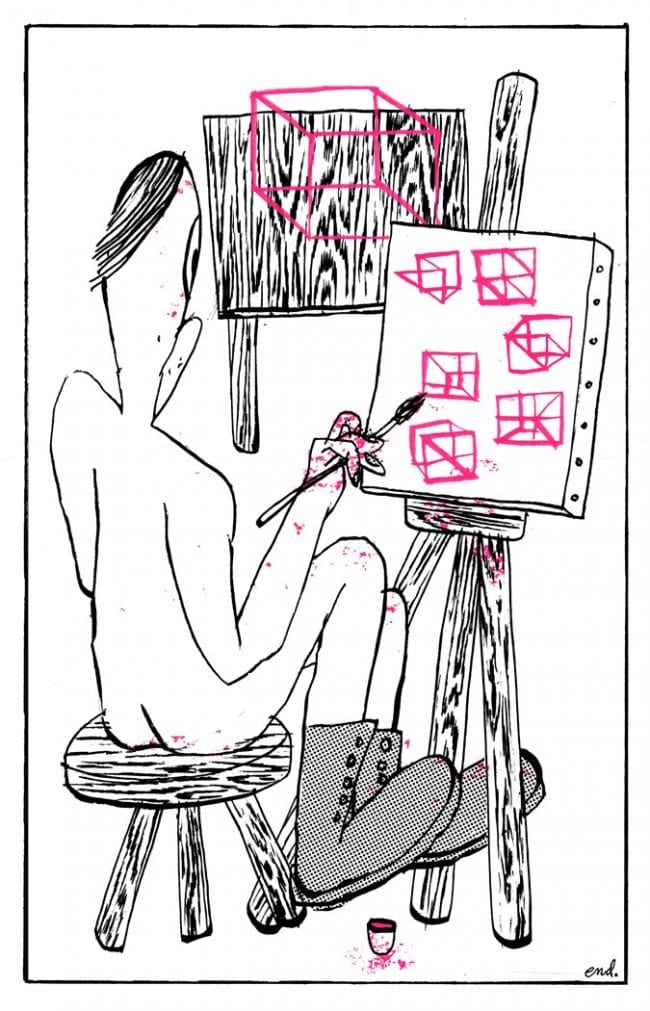

Your paintings give the viewer a little extra time to breathe. There isn’t that breakneck pacing, like in some of your comics. You believe that your paintings are stories unto themselves?

Yes, they usually end up telling a story. An idea as simple as two figures entwined can tell a very complex story, depending on how deeply it resonates with the viewer. Even an abstract work can feel quite narrative to me, you know? As in, “What events lead up to this moment captured in this painting?” and “What events took place as a result of this moment?” I do tend to have very quick pacing in my work as a result of focusing on each panel as its own piece. At the moment, I am very excited by slow pacing. Pages that have the same panel repeated eight times, perhaps with just the slightest minute variations are fascinating to me. I’d love to do an entire book that way.

Have you always been intrigued by abstract art? For me, I don’t think I was able to really appreciate it until I grew up a little bit. It was a lot of that “What’s the point of this?” early on.

I didn’t connect with abstract work until college. I took out a VHS tape from the library called Painters Painting about the abstract expressionists of the ’50s and ’60s. The artists seemed really cool. I was 18, so being cool seemed important. I may have been drawn more to the idea of being like one of those people. Now I connect with abstract work on a more visceral level.

Do you remember what painters struck you as cool?

They all seemed cool. It was like that Beat Generation of artists that romanticized things like being an alcoholic, or having so much passion that you neglect your family. Cool dudes! I’m generalizing. I’m sure there were some good people. It’s just funny how perceptions change as you grow older and have children. I do remember Robert Rauschenberg coming off quite creepy in that documentary. He would talk in this very monotone way and then at the end of each sentence he would pause for a moment, then flash a sharp grin.

You draw several instances of unsettling violence in your comics. We’ve gone over the fall from the ladder in "The Character", but you also use the old cartoon trope of hitting someone on the head with a frying pan in "Lands Have Mercy". Most cartoons would have that person grow a mountain-sized lump or have birds whirling around their head, but you dedicate an entire page of blood slowly rolling down the person’s face. Why do you use those sudden flashes of stark violence as turning points in your stories?

I love the way they would draw that pink lump just tearing through the fabric of fur at the top of the head in those old cartoons. Tom and Jerry used that quite a bit. In that particular instance, I wanted the sequence to feel very realistic, like the psychedelic fantasy is over. This cartoon character can bleed. In the next sequence, the character who hit him with the frying pan prays for him not to die. Now, in my mind they have gone from cartoons to a sweet young Southern couple who are meeting for the first time under some strange circumstances. Cartoons are a language that I connect with very much. When I was a kid, I watched TBS every morning from 6 a.m. to 8 a.m., and classic cartoons would run. This is what I woke up to for the first 17 years of my life. So, cartoons and their language and symbolism are deeply ingrained in me and have found their way back to my work.

But your use of violence isn’t as throwaway as in the Tom and Jerry cartoons. It lingers. It seems more purposeful and sinister.

I like for there to be consequences to violence in my work. Tom would just show up in the next scene without the lump. My character almost dies. As absurd as it may seem, there is something very powerful to me about a cartoon character going through trauma. My daughter is that way with her stuffed animals still. If one of her stuffed animals were put in a make-believe situation in which she felt it was being threatened, she would become very emotional. That’s is the type of sentimentalism that I cannot avoid in my comics.

Then you take that sentimentalism and juxtapose it with over-the-top absurdity. Is that tightrope difficult to navigate?

Not at all, because I don’t consciously make those decisions. I’m satisfying an urge. Absurdity can lead to humorous and frightening situations and I like creating worlds where those coexist. The sentimental influence serves as a conduit for me. When the work comes from a deeply personal place, I stay engaged.