GB Tran is a cartoonist, designer, and illustrator whose graphic memoir Vietnamerica: A Family’s Journey was nominated for an Eisner for Best Reality-Based Work. It won the Gold Medal in Sequential Art from the Society of Illustrators and was listed as one of the “Top 10 Graphic Memoirs of all Time” by Time Magazine and one of the “Top 10 Graphic Novels of 2011” by Library Journal. Tran also teaches in the M.F.A. in Comics program at the California College of the Arts and has lectured widely at colleges and universities. This interview is based upon two conversations at his home that took place in August 2019 and October 2019. All images are courtesy of GB Tran. Interview by Jeanette Roan, Associate Professor, History of Art and Visual Culture Program and Graduate Program in Visual and Critical Studies, California College of the Arts

Beginnings

In interviews you’ve mentioned that you made your first comic when you were ten years old. It was called X-Out—no connection to Charles Burns I assume—and it ran for four and a half issues, but it was very rare, a run of one.

GB Tran: One could think of it as an artist’s monograph. The title was a rip-off of X-Men. I was not reading Charles Burns when I was ten years old.

Right, it was more of an artist’s book. Although you were into comics when you were a kid, as well as in high school and college, you didn’t start really making comics until after college, when you moved to New York City. Why not?

New York was the first time I was ever in a situation where I met other people who did comics. The camaraderie, the energy, having a community. When I moved to New York I was twenty-four, and that was literally the first time in my entire life that I met other cartoonists who were seriously wanting to do comics. Literally the first time. I mean, I went to conventions and stuff, so I met people, like I’d stand in line for Todd McFarlane to sign Spawn issue #1 but I don’t count that. New York was the first time I met people my age, at my time in life, who just really wanted to make comics. Some of them really wanted to make comics for a living. It wasn’t like they wanted to draw X-Men or Batman, they just wanted to tell stories in the comics form. This was in the early aughts, and it was fantastic.

Did you get together and have something like drink and draw nights?

No, because I’m not very social. The closest thing was figure drawing. There was a whole SVA [School of Visual Arts] crew: Tomer Hanuka, James Jean, Esao Andrews. I’d never been in that situation before because I went to school at a state university and in general the people who were in classes with me didn’t really have dreams or aspirations of being artists. New York was truly the first time I was around other people who were really passionate about art, who were really working hard to sustain themselves and support themselves doing it, and that was an epiphany, that was eye-opening to me. Also, going to conventions and stuff like that. Before New York I went to conventions, but it was as a fan. It wasn’t until New York, after meeting other people who were doing comics, that it occurred to me that maybe instead of going to festivals and conventions as a fan, maybe I could go as an exhibitor

You received a Xeric for something called Content. What was that about?

It was just a little fiction “what if” story. It was forty pages, and it was the first comic that I ever published. I remember it clearly. I applied just as a whim. I heard about it after I graduated from college and thought “I should apply for this.” So, I put together a book, sent it, and then moved to New York and forgot about it. Six months later they reached out and told me they were giving me a grant to self-publish it. Being in the New York community, being around other people who, for the first time, were super passionate about their work, and then also getting this kick in the butt, this $5000 grant to publish my book—it was all perfect timing. I printed a thousand copies and the book was distributed through Diamond, because that’s part of the Xeric grant, to show self-publishers the entire process. It wasn’t just to cover printing fees. It was to show how you make an ad for your comic and turn it in to the Diamond catalog, how you list your book, how you promote it, how you get people to order it. The Xeric grant basically taught me more about comics publishing than I’d learned up to that point.

Vietnam to South Carolina to Vietnam

You hint at this a little in Vietnamerica, but you grew up in South Carolina in the seventies and eighties, right? I’ve heard you say that your parents went to great lengths to drive you places so that you could play with other Vietnamese kids. What was it like being a Vietnamese American kid in South Carolina?

Yup, seventies and eighties. I don’t remember anything, honestly, because I left South Carolina when I was fourteen. The thing is, when you’re growing up in a place, you don’t know if what you’re experiencing is just normal growing up or if it’s different from what it’s supposed to be because it’s the first time you’re experiencing it, right?

You didn’t feel different?

I can say that I don’t remember having those feelings. I’ve had these conversations with my wife, and she’s suggested that I just suppressed them all, and I think she’s probably right. I mean, that’s how I cope with things. Or more accurately not cope with things.

As a kid, you might note things, but you don’t necessarily know what they mean yet.

Yeah, like growing up, in elementary school, other kids called me “chink.”

Did it bother you?

Every kid was being called a crappy name. I wasn’t the only one being called a bad name, so to me, I don’t know, maybe it did register and I’ve just suppressed it.

For some kids of color, growing up, X-Men spoke to them because it was about difference. For example, Sana Amanat, the woman who is responsible for the Kamala Khan Ms. Marvel series, said she became interested in comics through X-Men. Was it that way for you?

Maybe it was for my brother, but I just liked it because there were some cool people, shooting laser beams out of their eyes. It’s interesting though. You brought up those anecdotes about growing up, like my parents taking us to learn Vietnamese at some random dude’s garage on the weekend, or driving really long distances to play with other Vietnamese refugee kids. Of any memories I have of growing up in South Carolina, those are probably the source of the most memories, so a part of me wonders if, because my parents went so far out of their way to have us be with other Vietnamese people when all I really wanted to do was play with my neighbor or watch Saturday morning cartoons, I wonder if that just pushed me in the other way, to not want to think about my Vietnamese heritage? I never thought about it that way until now. If I think of whatever few memories I have of South Carolina, they all involve being with other kids, like I remember one kid, he had an older brother and we drew a lot together. We hung out, but it wasn’t because I liked him, it was because my parents were friends with his parents, and they weren’t even necessarily friends. It was because they were all refugees, and they formed a community, right? Because you know, we were in South Carolina. Growing up in South Carolina, my mother magically made dinner every night even though she had one and a half jobs and four kids to take care of. That was a huge thing. But even more huge because she was in South Carolina where they didn’t even know what Vietnamese food was, much less actually stocked the ingredients to make Vietnamese food. So for my parents, there’s just like this morsel of Vietnamese culture we have to hang on to even if we have to drive one hour to hang out with these people. So those are my memories, so maybe a part of me felt like if I don’t have to embrace this Vietnamese culture and stuff, if I can just be a kid and play with my neighbor, you know, then I’m going to choose that.

The parts of Vietnamerica that I identified with the most were the ones in the middle about growing up as a child of people who were new to the U.S. They made me remember my own teenage years, and now I feel terrible about some of the things I said and did. You put some of those things in your comic book for everyone to see!

I didn’t think anyone was going to see them! I still clearly remember making fun of my mom, and I feel awful. It was at a restaurant, and my uncle just totally went off on me. He said how dare I make fun of my mother’s English, it’s not her first language. It’s making me flush now, thinking about it. As a shitty kid I was like, “Oh, I was just making a joke.” It’s the only memory I have of my uncle getting really angry with me. And he’s an uncle I was really close to, because we’d hang out together, watch movies. He bought me a lot of Legos.

Then you went through the process of drawing it.

It was cathartic!

I think it’s just that at that age, and I think part of it is not being white in a majority white context, you don’t want to be different from everyone else and one of the things that makes you different is your parents’ accents in English. You felt better after drawing it?

Yeah! Totally. Putting it on paper. If I don’t put these stories out there, they just stay in my head, these memories just stay in my head. It was good to put them out there, get them out of my head so I don’t have to think about them anymore. It’s also archiving it so that someday my kids can read it and maybe not be as shitty a kid as I was.

Did you speak to your parents in Vietnamese?

Yeah, in the house, we were always required to speak Vietnamese. The Vietnamese school was for reading and writing. In the house we had to speak Vietnamese with the proper pronouns, and respectfulness, and all that stuff, absolutely.

You didn’t put that in the book though.

No, because for Vietnamerica—I bring this up every time I talk about it, especially for class visits when we can go more in depth because they’re read the book—I’m trying to tell the smallest story possible, and the smallest story in Vietnamerica is my parents’ journey, and the perspective of me learning about it. There are all these other things that could be in the book, but I edited them out because I didn’t think they propelled the story, they would have been tangents. I didn’t want a 300-page book to become a 450-page book with all these tangents. A lot of stuff got left on the cutting room floor because it just didn’t make sense as far as what the core story was. Some of the stuff was pretty cool, some of it was kind of controversial. I feel like the essence of the strictness of the household that I was being raised in does come across in the book, without having to beat the reader over the head about it because that’s not the main point.

That makes sense. It’s interesting that Thi Bui’s book The Best We Could Do has a lot more about what happens after they arrive in the United States, so there’s a different kind of balance of emphasis in your two books. On the surface the two books seem similar, but they’re actually completely different.

I joke with my students at CCA [California College of the Arts] all the time, because Thi also teaches at CCA, about how they are living in a world in which in this program, there are two Vietnamese American cartoonists whose major graphic novels are stories about their families leaving Vietnam. It’s crazy! But that’s exactly right, they’re totally different stories. That’s the point I want to make. We’re living in a golden age where you can say that, and yet still have the stories be so radically different. In tone, in content, in what they’re trying to do with the reader, in the journey they’re trying to take the reader on, they’re so radically different.

In a conversation you had with Thi that was published on the Hyphen website, you described your drawing style as a more rendered one that kept your emotions in check, whereas hers was much looser and more emotional. Could you say more about that?

She would be better able to answer this than me, but to the best of my knowledge from our conversations, I think one of the really big early things that nudged Thi down her cartoonist path was the Atlantic Art Center’s artist’s residency. The person she worked with was Craig Thompson. You know his line work, right? I think her early work was really influenced by the tools that he was using, and the expressiveness of his line work. In contrast, I grew up on Jim Lee’s X-Men, so my early inspirations were totally different. As far as just looking at it within the microcosm of comics inspiration, they’re very different routes. Mine is years and years of growing up reading all these superhero comics, and then moving into European comics work, and then a very long phase going through manga, so this idea of super expressive, simple characters, but placed in super detailed, very concrete surroundings and environments. These are all things that inform the way I draw, so I think those are probably the biggest reasons for the differences in the approaches we take to our art.

There are very few backgrounds in her book, whereas you have incredibly detailed backgrounds with lots of buildings, people, etc. The effect for me as a reader is that you’ve placed a lot more emphasis on the specificity of place, whereas Thi’s book is much more about people’s emotions.

For me, telling stories is heavily influenced by this idea in manga where the environment is as much of a character as the characters in the environment. When the story happens in a place that not all of your readers may have been to, and they may not know what it looks like, it’s really important for me to capture the details of the place. That’s why, as part of the process of writing Vietnamerica, I went to Vietnam a couple of times. A large part of those trips was sitting down for hours and hours and just drawing the scenery. It wasn’t because “I’m going to put this scene in my book” because at the time I didn’t know it was going to be a book, but that’s just how I get to know a place. When I traveled with my wife, before we had kids, we’d go to a place and I would sit down somewhere and ask her to come back in two or three hours. I would just draw the entire time because that’s how I experience new places, I sit down and just observe. I like to see the rhythms of life—what are the people doing, what types of interactions are they having, what’s the street traffic like—and that’s how I feel like I start to learn about a place. I did that in Vietnam. I wanted to convey that in my stories, because that to me grounds the story.

It’s also about contrast. The way I work—here’s an analogy—if I want to highlight a funny moment of my story, then I would surround it by some sad moments, so it’s a juxtaposition. The funny thing that happens feels a little sillier and more humorous because at that moment the reader’s mind is in a different place. So, this happens at least once a chapter in Vietnamerica, I want a powerful splash page that’s kind of abstract, has an editorial vibe to it, like it’s an illustration that you could see with a New York Times article or something like that. To give those kinds of beats in my story more weight I want to ground all the pages that come up to it in more representational, world building pages. Like, now they’re walking through the street, and there’s a truck that comes by, “put put put put put,” with effects, and there’s some people eating noodles on a table, so there’s this really rendered environment that you’re really in, and then you turn the page and you see this abstract editorial image, and to me that hopefully gives it even more punch because of the contrast, the juxtaposition of visual narrative. If every page looked the same, then after a while as a reader, you’d just be like OK, flip, OK, flip, OK, flip.

Storytelling and Emotion

At a talk at the San Francisco Public Library, in response to a question, Thi said that drawing her parents over and over again was an act of love. Is this something you relate to in terms of your process?

It’s really interesting to hear that Thi said that, because drawing my parents over and over again was not an act of love. I’m not saying I hate my parents or anything like that, but for Vietnamerica, and even now, I would have concerns if I was telling the story or drawing the story in a way where I felt a connection to the characters while I was doing it, because then that is a subjectivity that I don’t want there as a storyteller. As a storyteller my job is to be real, and to be honest, and if I’m doing a story and I’m feeling a connection, that is a closeness to the material that I do not think benefits me as a storyteller.

Always? Would there be any instances where that might serve the story?

Always. I know this sounds weird, but if I’m working on drafts and I feel less and less emotionally invested in the story, I feel like I’m on the right track. I try to tell stories that are super personal, in the hopes of connecting with my audience on a deeper level. But I think the more personal it feels while I’m doing it, the more those feelings are potentially preventing me from telling the strongest story possible. So I try to work on my stories without having an emotional attachment to them.

Do you think that point of view could have anything to do with your science background?

Absolutely. Just for the record, I started undergrad as an astrophysics major. There’s a very cold, calculating process to the hard sciences that I love. That’s what attracted me to it. There’s no emotion to it. There’s no, like, I’m super attached to this integer formula. That totally is the way I approach my storytelling. I don’t care what it’s about, whether it’s about me, whether it’s about my kids, whether it’s about my parents, I don’t want to be driven by any feelings when I’m doing the story.

How do you know if the story is working or not if it’s not about your subjective sense of it?

I let other people read it. A friend of mine who’s a writer was a huge part of editing Vietnamerica. I gave it to him before I gave it to my editor to look at it. He has a brutally honest eye, and his perspective on life is similarly aligned to my perspective on life, so whenever he’s available he’s the first person I show my roughs. I ask him how does he feel when he reads it? The advice he gave on an early draft of Vietnamerica was that I’d done a great job of getting my family’s history down, but I had done a terrible job of making it into a story. He had a point. I deeply value his brutal honesty, because I know this too when I give feedback for other people, it’s definitely a lot easier to be critical of another person’s work than your own. So that’s how I know. I give it to him, he reads it, he lets me know how he feels reading it, and then he offers me suggestions. I can’t just trust my own opinion.

So you’re kind of working off an instinct about what serves the story, and then you double-check it with him in terms of whether you achieve what you’re going for?

Well, it’s not so much what I’m going for as whether something really important I wanted to put in there did anything for him. I go for emotional honesty. I think that’s the only thing I go for.

You’ve mostly done non-fiction. If you were doing something fictional, would you still be going for emotional honesty?

I think so. That’s what I find most compelling. The types of stories that I love the most are the ones that are really emotional and that are so personal that you can’t help but put yourself in the person’s shoes. For instance, today I was listening to this program called The Moth. It’s a radio program where people just tell stories. It’s really great because they’re very emotional, very poignant stories. The most recent one I listened to was about an electrical engineer who was there during the Fukushima nuclear meltdown. On one level, I listen to it and I’m really emotional, really moved. But I also think, why am I moved? It’s because at the beginning of the story there was this anecdote about how every morning before going to work he’d swing by this old lady’s food stall and pick up food. He never knew her name. Then the Fukushima disaster happened and he was obsessed with trying to make sure she was alive, and he finally found out her name.

I think you’re trying to create stories in an unemotional way so that they will be as emotional as possible. In the world of comics, who does this better than anyone else?

Chris Ware, absolutely. Chris Ware is a master of creating emotional impact in his stories without falling on the common devices to squeeze emotion out of a reader. It’s not about drawing a close-up of this character with tears, it’s all very cold, calculating, methodical. There’s a little visual distance between you as a reader and his characters.

Did his work shape your storytelling in Vietnamerica? If not, what were important influences for you back then?

If you’re asking what my primary creative influence for Vietnamerica was, my answer is Frontline, the PBS documentary series. It’s an hour episode every week, and it discussed everything from the controversy around GMO foods, to corruption and politics, to the extinction of a certain animal.

I’m not sure I see the connection.

The connection is the storytelling. It was the structure of the documentary within that format. They would interview people, but they wouldn’t be emotional, decrying Monsanto as an evil corporation that was killing people, and then the producers cutting to a scene of something sensational. They would show some person sitting in a chair, talking about what Monsanto was doing, and all of the consequences that would follow. I became very emotional watching it because the story was being told in such a very straightforward way that it felt—this is part of the trick of storytelling—it felt very objective, and that had a really profound effect on me. It was very meticulous, methodical storytelling on a range of subjects, and it was able to get me really angry about things I never thought I’d get angry about, like crops. That, to me, is a testament to storytelling.

Artwork and Artistic Influences

We’ve mostly been talking about how you write stories. Could you talk about your drawing process and what kinds of materials you use?

Now I'm purely digital. The only analog part of my drawing process is initially in my sketchbook. That's because that's where all my ideas start. It's just clearing out all the initial thoughts. Your first idea is usually your worst idea, your second idea is your second worst, and so on. So that's the only analog part of my artwork is just getting out all those bad ideas, the easiest ideas that come to mind. After that it’s purely digital. I work on a Cintiq, which is a large desktop screen that you can draw directly on. A lot of my fellow cartoonists actually work on tablets now, whether it's the Surface or iPad, because of convenience, but also because Adobe just got a new program called Fresco. I feel like this is going to dramatically change a lot of the artwork that we're seeing by people like illustrators and cartoonists because, for the first time, it's a program that actually recreates the behavior of painting accurately to actual painting, like with watercolors, the transparencies, the blending, all that stuff. In the past, digital programs haven't been able to nail it. But this is the first time I think it's absolutely fantastic, amazing. I think it's just groundbreaking. Unfortunately, Adobe Fresco is only available for tablets. They know their audience is trending towards people who work on tablets, not at a table with the desktop computer, which is me.

The Cintiq is actually a very common tool. I think it's kind of considered old school because of all these great drawing programs for tablets. But I don't see a time where I could work with tablets. First off, I am in love with print. With everything I do, my hope is that it sees print, and not live on the Internet on an infinite canvas. I'm in love with the idea of having print and having a physical, finite dimension, with a left and a right page. For me, it's really important to work in a way that allows me to see the left and the right page at the same time at all times because that's the composition. It’s not just the left page. It's not just panel one of the left page, it's the entire left and right page and the entire spread. Working on a tablet would not allow me to see this entire canvas at print size. I could see it if I shrunk it down. But then to me that's tricking your eye, because you're looking at something that's half the size that it's supposed to be looked at. How can you make aesthetic decisions or compositional decisions or flow decisions when you're looking at something that's that much smaller than it's actually going to be when someone holds it physically in their hands? So it would be very difficult for me to make the transition to a tablet. A Cintiq allows me to look at my left and my right page simultaneously as a singular spread at print size, because the screen is large enough for that. And then from there I go through all the traditional steps of roughing out a page and then penciling it and inking it and coloring it, and it's all done digitally through, currently, Photoshop. But I am slowly in the process of teaching myself a little more about Clip Studio Paint, which is more like a comics drawing program as opposed to Photoshop.

You know how Jessica Abel’s and Matt Madden’s Drawing Words and Writing Pictures ends with a section at the back about tools for cartoonists, like a blue pencil, different kinds of pens and brushes, and the like? Do you still teach using these tools and that process to your students, even though so many people are working almost entirely digitally now?

An Ames guide for lettering… No, I don’t personally. At CCA everybody's working on their iPads and to me, that’s great. There's so much you can do digitally that just makes it so much more streamlined. I mean, it's good to know the history of it, for sure. And I still use tools like blue pencils, and regular pencils, and different types of brushes and stuff like that. Just digital versions of them, that’s all.

Why do you actually need the blue pencil step, since you’re not really worried about it showing up on the photocopier? Are you using digital versions of these tools to work through the process in a familiar way, but you could just use the same “pen” to do all of the steps?

You could, absolutely, and it'd be pretty straightforward. Vietnamerica was the last major project that I did analog. I had the opportunity to transition to digital earlier. At the time, a lot of my cartoonist friends had already started working digitally, and I could see the benefit. For me personally, I promised myself that I would not go digital until I felt super comfortable with the way I work because I didn't want a situation where I go digital and suddenly this entire new universe of processes is available to me. I wanted to be comfortable and confident with the way I work. The advantage of going digital was purely about time and efficiency. That said, a few years later, after I felt completely comfortable with working digitally, I started loosening up and allowing myself to deconstruct how I make pages. I don't have to do blue line, pencil, ink. I can do blue line, ink, and then maybe do some shape work, and then go back to inking more and then maybe doing some more shaping. That's allowed me to try out different styles, which is really important to me.

One of the most striking things about Vietnamerica is how you switch between different visual registers. I’ve heard you describe those contrasts in terms of your illustrator’s response to different types of things going on, and how it made sense to have different styles for those events.

My day job is as an apparel graphics designer and illustrator. One of the most fun things about the job is that we try to create artwork that's on trend. Every season is not going to have the same style or hand. I enjoy that because it's basically playing with new techniques on a regular basis. It can be doing something that feels very painterly or doing something that feels like really clean vector line art in Illustrator or doing something that is more graphic, like a woodcut print, or whatever. I really enjoy that because it gives me the opportunity to play in a situation that is very “un-precious.” It's allowed me to continue to experiment with a lot of different hands, a lot of different styles, not feeling that my work has to look a certain way. That totally informs the way I approach my visual storytelling. I want to draw artwork that is best suited for the story I'm trying to tell. I mean, overall, I think all my work looks like it’s being made by the same person. But there are, to me, some variances. For the most part, for each project I've done, I can look at it and think, “Oh yeah, that's the project where I started doing this new thing.” I was always taught, for example by art directors, that you have to have a defining look or hand to your work so clients don't have to guess what they're going to get from you. Are they going to get something ultra-realistic with a lot of cross hatching, or are they going to get something that's more abstract? That totally never appealed to me. I always wanted to change it up.

In Vietnamerica, for the communist propaganda pages, and for the Tintin-like “Ligne Claire” pages, did you go back to those originals to look at them and study them?

Yeah, totally. That's the beauty of the internet. You can just type in “Vietnamese communist war posters.” The imagery that I was using for them was definitely imagery that I felt was common in a lot of posters, like the hands and the birds and people looking up at the sky at absolutely nothing. For the Hergé-like pages, there’s one particular sequence where I literally copied and pasted Tintin panels and rearranged them into a page layout because at that point, I knew there was a scene where my dad is going off to school, and he's really excited about leaving home, and he never wants to go back. I clearly remember seeing a Hergé panel where Tintin is jumping on a chest to close it. I decided I was going to do this panel, but it's going to be my dad jumping on his luggage, closing it because he's so excited to get out of there.

Were there other kinds of visual references that you were thinking about when creating Vietnamerica?

I think those were the main ones. And of course, there's the one page where it's all photography.

Were you familiar with those photos when you were growing up?

No, I found those when I was visiting Vietnam. They weren't in the picture frame in the hallway in South Carolina. There are some pictures, for example a picture of my mom posing on a motorbike, that my dad didn't like at all because that was from before they were together, and the motorbike belonged to her old boyfriend. The photos were in a little cookie tin. I opened it up and saw these pictures and said “Wait, who's this woman”? I was told, “That's your mom.” I asked to borrow them, brought them back to the States, scanned them in and then sent them back. They’re even more special because after the fall of Saigon, a lot of photographic evidence of whatever life people had before was burned because they wanted to destroy any evidence that could be incriminating. I can't imagine all the pictures that were lost. It was really nice to see the ones that survived. In a weird way, what remains is this kind of fantasy, a romanticized history of all the wonderful parts of their life growing up, of them posing on a bike, going on a swim, being at the beach. But I know that wasn't their lives. I know their lives were much more difficult. I don't think my parents had a childhood. They grew up in multiple wars, they had to survive. I know the household my father was raised in, so these pictures are kind of like lies. Those were small moments of their life. But for the most part, they didn't have space to be young adults. My mom left Vietnam when she was twenty-four, so she didn't have a life of just going to the beach and having these sweet moments with her kids.

It seems like part of your rationale for showing these photos of your parents as young, happy people was to contrast them with the past one-hundred-and-fifty pages telling readers about the reality of their young lives.

That was really important to me because when it comes to memoir, if there are photographs, they are in there to give the story that extra, deeper connection, just to remind the audience that this was real, this is visceral, these are real people. For me, it wasn't a question of whether or not I was going to use photographs, because I definitely was going to do it. The question was how, and more importantly, where. There’s a reason there's only one spread, that photo collage, literally at the halfway point of the book. I wanted the reader to be reminded that these are real people after they spend some time learning about the difficult childhoods they had. Then there’s this contrasting beat, this collage of them being extremely happy for this one brief moment in time, which is in the middle of the book. And then you read the back half of this book, and it gets even more batshit crazy. It’s probably one of the things I'm happiest about in terms of what I did with that book, that moment. It's not the last thing you see so it's not the last impression you have of the story. It's not your initial impression of the story. It's just that sliver of the story where my mom meets my father for the first time as his student in class. Obviously, they become romantically involved and they have kids, etc. But that moment, to me, is the happiest moment in the story.

There is a page in Vietnamerica that shows some comic book covers, among them, Art Spiegelman’s Maus. Was Maus an influence? It seemed like a lot of your early comics reading was mainly mainstream superhero comics.

Yeah, I was a spandex and tights guy. Maus is there because it was a part of many books that I found very influential. When I first saw it I thought, “Oh, this is really cool. I've never read a comic about the Holocaust! I didn’t know you could tackle the Holocaust in a comic!” What it represented was amazing.

Who has been an artistic influence for you?

You know, my default answer is that I find inspiration everywhere. You know, “Learn from everyone but follow no one,” which I do genuinely believe. But artistically, Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt, Alphonse Mucha, to me, those three guys are huge. In Egon Schiele’s work, the ways he is using his line as expression, and how incredibly raw the images feel, is really beautiful. Gustav Klimt, his work is so decorative and really elegant. I think Alphonse Mucha’s line work for The Seasons and all this incredibly ornate framing work was what I initially really enjoyed about him, but then I discovered his paintings. He did this whole giant painted mural series, the Slav Epic, that depicts the history of the Slav people. And it's just gorgeous, because it's not like his line work stuff, where it's just featuring one female figure. It's huge, expansive, with crowded scenes and really beautiful, powerful stuff. I wouldn't say these are my primary influences, but these are the ones that have stuck with me for my entire path as a visual artist, for sure.

I didn't realize you were going to name fine artists. I thought you were going to talk about cartoonists.

Well, I'll still read anything Brian Hitch draws. Or Frank Quitely. Bryan Hitch did this series called The Authority. Then I think he reached the next level when he did The Ultimates, which was basically all Marvel's superhero characters, but with an alternative history. I first noticed Frank Quitely when X-Men did this kind of reboot, in the early 2000s, and he was the artist attached to them. They were called The New X-Men. When I first saw his work, it was like, whoa, this does not look like any other spandex artist I've ever seen. Just awesome, really beautiful. The figures are stylized, but not in the way that I'd come to expect, having read superhero comics for twenty years. There's a lot more curves and bumps and bulges that felt a lot more voluminous and tangible. He had more of a nuanced expression of people's faces, not always super angry or super happy, but with variations. They’re subtle, just really beautiful, beautiful work. And his line work is just gorgeous.

Before and After Vietnamerica

Within Vietnamerica you make clear that one of the big motivations for the work was the passing of your grandparents. But I’ve also heard you mention a health crisis that precipitated the work?

In 2004 I had a brain hemorrhage, and it wasn’t because I was doing massive amounts of coke.

Just to be clear.

The ER doctor said to me, “You can be honest with me, do you have a drug habit?” I said no, I don’t even drink coffee. It wasn’t because of anything that I did, it’s a genetic thing, that’s just the way it is. So thankfully I lived, it healed itself, I didn’t have a lobotomy. The big epiphany I got from that experience was, and it’s still my daily mantra, as cheesy as it is, is basically that there’s not enough time in my life to do everything that I want to do. But I also genuinely believe that there’s just enough time to do the most important things. That’s been my guiding mantra every day since. There are so many choices, so many paths you can take. Usually when I feel like I don’t know what I want to do, then I think OK, what’s most important to me right at this moment? That usually gives me my answer, and there’s no regret.

I’ve wondered about the timing of the release of Vietnamerica, and what might have been different if it had come out four or five years later, say around the 40th anniversary of the fall/liberation of Saigon in 2015 when there was a lot of popular and media interest in looking back at the American War/Vietnam War.

Oh yeah, absolutely, to be completely transparent, that thought always crosses my mind. Look, if you ever devote a huge chunk of your life and your energy and your creative passion into a project, and then something happens later that could have helped it find greater critical or commercial success, then of course you can’t help but wonder about what might have been.

But Vietnamerica did find a lot critical acclaim, it’s been taught in college courses, and there have been quite a few academic, peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters about it.

That’s cool, and I’m super duper appreciative of it. When I went to school, there weren’t any courses that taught comics. The irony of me being a part of an MFA program teaching comics right now is not lost on me. But at the time when I was working on Vietnamerica, even though the boom for “graphic novels” had occurred because of Persepolis and Fun Home, I don’t feel like they had found their foothold in the world yet, and certainly not in academia. While I was working on Vietnamerica, although my publisher may have been thinking this, I wasn’t thinking about how cool if would be if this book was assigned reading in a class one day and I could do a talk about it. But after Vietnamerica came out, all those opportunities came about, and to this day I’m still stunned, and extremely grateful, for those opportunities because they opened up a new path in my life. They certainly resulted in me teaching, and then my realizing that I really love teaching. I never want to project a sense that I don’t appreciate or am not completely shocked at what’s become of Vietnamerica because it’s incredible. I did a two-week writer’s residency at Tel Aviv University, and it was because a professor wrote a chapter about Vietnamerica in their book. My policy is that whenever I hear somebody’s writing something about Vietnamerica, I will try to reach out and thank them. So I emailed the person and said thanks. I told her I never dreamed that Vietnamerica would have a home in academia, so I really appreciated her work and would love to read it sometime. She sent me a PDF of the chapter, and then three months later, she emailed me out of the blue and asked if I would consider going to Tel Aviv University and doing a two-week writer’s residency. Life is not a direct, straight path. It’s twists and turns, ups and downs, and all the stuff that’s resulted from Vietnamerica has been totally unexpected and really wonderful, and I’m so grateful for all of it.

Have you ever received any negative reactions to Vietnamerica?

No, I think a lot of people were just really excited that it existed, and they weren’t going to nitpick it. But I think now, when there’s a lot more that’s coming out, a lot more pieces and work about it, then maybe that’s an opportunity for people to be more critical. I think if you’re the only thing that represents a certain marginalized voice or demographic that hasn’t been very represented at all in this medium, people aren’t going to just start doubting you and piling on. I mean, back in the day. Today might be different.

I don’t know, Margaret Cho’s TV show All-American Girl was not very well received by the Korean American and Asian American communities.

Yeah, but the difference is that was because it was popular. Vietnamerica, in its first year, sold maybe three thousand copies? It wasn’t on anybody’s radar. I imagine it’s just a tipping point, right? If your audience grows to a certain size then of course there are going to be more voices that are critical of it. But if your audience is very small, then I don’t know if that small audience is going to have a lot of critical voices in it because that audience might just be happy that the work exists.

You did post that one-star review of Vietnamerica from Amazon on your Instagram. I don’t think you should take that personally because it was about comics as medium.

I posted it on Instagram because I think it’s funny! If I was a student in a history class, and I had to read Vietnamerica, I might be like wait a minute, this is a comic, what’s a comic doing in this class? The fact that the student was moved to post a review on the Amazon page, I think it’s funny.

Exhibiting and Finishing

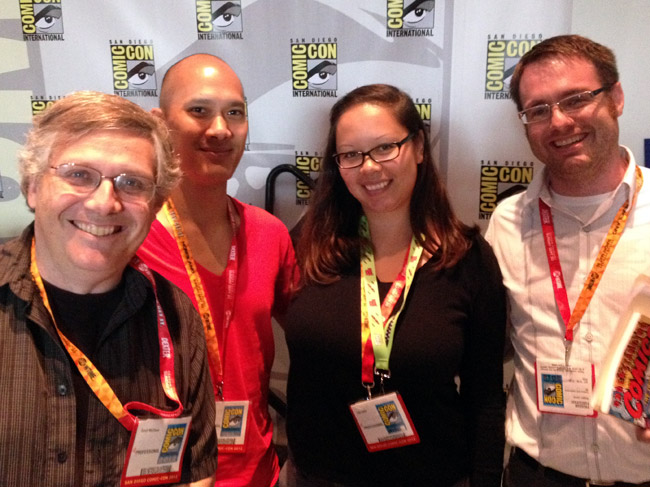

Do you still keep up with the news out of San Diego Comic-Con?

It’s always a rad bummer that time of July. It’s rad because I’m like, San Diego Comic-Con! And a bummer because I remember when I used to go there. Despite what it’s become, I would go in a heartbeat to exhibit out in San Diego, if there were no repercussions with my wife or my children because I left for five days. I hope that when my kids get old enough I’ll be able to take them. I love doing shows. TCAF, Toronto Comic Arts Festival, is hands down my most favorite show that I ever did. A close second is SPX [Small Press Expo] in Bethesda, Maryland. And then of course there’s the MoCCA [Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art] festival which is in New York, and was my hometown show for thirteen years or so. When Vietnamerica came out, although there are a lot of fun things about doing shows—the camaraderie, the discovery of incredible work, selling some stuff and finding new readers—the greatest joy that I had was actually meeting people who didn’t know who the hell I was, but came up to me and told me they bought my book and really enjoyed it. For me, it was an opportunity to shake their hands physically, and thank them for spending their money and time to read my work. It wasn’t about trying to break even, it wasn’t about trying to network or anything like that, it wasn’t even about hanging out with fellow cartoonists. I mean, those are all positives, but by far the most valuable thing I got from shows was meeting strangers and saying thank you for looking at my work. Of course, that’s just an aspect of being a cartoonist. There are cartoonists who refuse to do shows. One of my closest cartoonist friends, he hates doing shows.

It’s very social, having to talk to people for eight hours a day, three days in a row.

It’s very hard work. I consider myself an introvert, which doesn’t mean you’re not social, you can love being social. It’s just that when you’re social it’s very draining, and you need quiet alone time to recharge. The cartoonist lifestyle is perfect for me. The majority of the time you spend by yourself, working, concentrating, and then you have these bursts of being social, like doing a show for three days and you have an amazing time, and then you recover. You go back to your room and make some more stuff.

There is something about the process of cartooning that requires a certain kind of dedication and focus, plus time.

That’s what I tell the students in my class. I let them know that the way I run the class, they’re never going to have enough time to finish the assignments. If they really want to do comics, they need to understand and have that feeling of having to finish something that isn’t up to the level or expectations or standards they want, but it still has to be finished. The hardest thing, harder than starting a comic, is finishing it. This is what I’m trying to embed in their minds, the feeling, the gratification, the satisfaction of finishing a comic, even knowing that there are so many things that could be fixed. That’s the way I felt about Vietnamerica, and I had two and a half years to work on that. After I turned it in, I wished I could have another month, or a week, or a day, or an hour, so that I could fix this, or erase that horrendous typo on the Scrabble spread where “foreign” is “e” before “i” and not “i” before “e”!

Oh no! I barely noticed.

But the thing is, you have to let go. It’s more important to just let go and be done, than it is to constantly noodle and fix.

I tell graduate students that you eventually get to a point where the best dissertation is a finished dissertation.

Oh, I’m going to use that. The best comic is a finished comic. I like it.

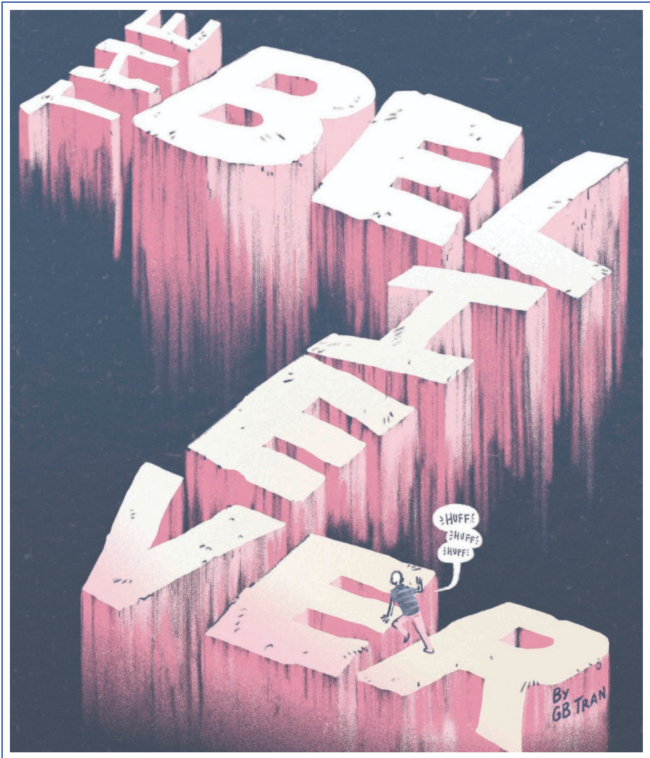

“The Believer” and Works-in-Progress

I recently read your Believer Magazine piece, “The Believer,” about your struggle to make ends meet in the wonderful but very expensive Bay Area, which I found heartrending.

That’s funny, I thought it was really uplifting when I was working it. It’s a weird thing, I gave it to the art director of the magazine, and they featured it on the cover of the issue. The descriptions was, “and from GB Tran, a story about fatherhood and failure.” I wouldn’t say I did a feel good piece, but however people perceive the ending of the story, I actually consider it to be a “happy ending” for me. It’s making a decision that results in the unknown that could possibly result in the improvement of one’s life as opposed to just giving up. I remember an interview with Neil Gaiman. Because he does a lot of stories for adults and kids, the interviewer asked, “What is the difference between writing for a kid and writing for an adult?” He said it was very simple: “When I write for kids, there’s got to be some sort of hope at the end of the story.” I thought that was beautiful. For me, that’s all I want, just some sort of hope. It doesn’t have to be a huge amount. Even if it’s just a glimmer, to me, that’s a happy story.

I do see what you’re saying about the ending, there is that glimmer of hope, but maybe because of some of our earlier conversations, I read that and then thought, are you OK?

Oh, interesting, so you read it from a certain perspective because you knew me, you knew more context. That’s sweet. I didn’t even think about that, for people who actually know me, know what I’ve been going through, they might be wondering “Was that story a cry for help?” People have different reactions to it. Justin [Hall] from CCA, he read it and told me he really liked the story and thought it was really powerful because it resonated with him in terms of making him think about what’s his future. In choosing not to have children, what’s going to happen to him when he’s old, but then it also made him realize what a privilege it is for him to be in a life where he can go do things like travel, or do a residency in the Netherlands for two months.

People respond in terms of their own life experience. But for me, it was also the fact that you were telling a story about not being able to make comics through a comic that made it more poignant. Part of that Believer story was about following your dreams, in a way, right? If you could have any sort of situation, what would be the perfect set-up for you? Would you be a cartoonist full-time?

If we’re talking about dreams, yeah, I’d love to be able to be a full-time cartoonist, of course I cling to that. That’s why I work on the weekends, that’s why I mentor in the CCA program on Saturdays and Sundays when I could just watch football on TV on the couch instead. All of the extra-curricular stuff I do outside of my design job is intended to keep me connected to my comics work as much as possible, hoping that there will be a time in my life when I can return to doing more comics work. I have a lot of stories that I want to finish.

What are you working on right now?

Well, I'm definitely in a transitional stage in my career. I have maybe four or five projects that have been spinning around in my head for the last several years. If I could work on them full time, they would take the next six or eight years of my life. One is a themed anthology about immigration. The Believer story was a test run for the other major project that I’m working on. Have you heard of a book called The Prophet?

Kahlil Gibran?

Yes. In The Prophet there are twenty or thirty stories that explore facets of life, such as marriage, work, joy, death, health, etc. I would like to do a version of The Prophet where each of my short stories addresses a certain aspect of life, through my lens, with my kids as the audience. The Believer story was about the theme of work. I’ve road mapped it out, its final form will take probably between twelve and fifteen stories ranging from I would say twelve to twenty pages each. I’m currently writing a few other stories right now, and the hope is if I can illustrate them, I could shop it around and try to find a publisher for it. It's interesting to me because whenever I talk about the other projects I've done, especially Vietnamerica, it's all been so methodical. But now, for me to tackle a project of this scope, not having it be methodical and just doing it in chunks at a time is the only way I can do it. I'm working on the stories independently, as singular pieces, but still with an idea of the ultimate vision. When I get to the point where I’m close to the finish line, then I can add the pages to really connect it all, hopefully. Fingers crossed.

Also, there was so much that I had to leave out of Vietnamerica because it wasn't part of the core story. I want to use this material for something. I'm taking that material, the bulk of it from our first trip back to Vietnam, and proposing a Vietnamese cookbook told in comics form. I didn't really appreciate what I had growing up as a child with my mother making dinner every night. It wasn't until I had children myself that I thought that I should really try to do for my children what my mom did for us. But I don't like cooking. When I was in New York, my idea of eating was buying a really large pizza and keeping it in the fridge for three or four days.

So not only did you not like cooking, I don't know that you were that into eating either.

Yeah, not really. But now I definitely enjoy and see the value of it. And I do enjoy cooking now because I don't get to cook very often. So, the cookbook is basically a Vietnamese cookbook, but told from the perspective of someone who learned how to cook in his adult life. It's told in the framework of stories from my trip back to Vietnam, because that's when I learned about my family, and met more family members. Food was an ongoing theme of that trip as far as the food etiquette and food culture. All the things— eating food I've never had before and seeing its place in the family and the household, like at dinnertime when everybody gathered, was really special. I know that's something that my parents tried to recreate for us growing up in South Carolina, but I didn't really see the full impact of it until I was in Vietnam for the first time. There's a lot of these anecdotal experiences that I still want to use that didn't make it into Vietnamerica because they weren't part of that central story. Now I've found this opportunity to combine it into a Vietnamese cookbook. Except that it's not supposed to be just a cookbook, it's supposed to be sharing a personal story that is enhanced by the recipes. It was very inspired by Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations, and this great Netflix series Salt Fat Acid Heat.

So to go back to the question, “What are you working on now?” I definitely have been and continue to be slowly pecking away at these comics projects, because comics is truly my love. And although I don't get to spend as much time on it as I would like—Which cartoonist does, honestly?—it's still so important to me to create projects. It's a small victory, because for a few years after we moved to the Bay Area, people would ask me, “So what are you working on next?” My answer for a couple years was, “Raising two kids.” Now when people ask me, that's not my answer anymore, which is really nice. That's a huge step forward in my book. Now when people ask me, I can talk about these projects that are still in the fetal stages, but at least my answer now is actually about comics.