Previously, the introduction, part two, part three, part four, and part five of our story.

Interlude

LONG BEFORE PRODUCING the comic strips Miss Peach and Momma, cartoonist Mell Lazarus was an editor at Toby Press, the publishing entity set up by Al Capp to publish Li’l Abner comic books and the ancillary products of Al Capp Enterprises. Toby Press was run, more or less, by Al’s brothers Jerome (“Bence”) and Elliott. In September 2012, I interviewed Lazarus on an array of comics-related topics, and during our conversation, he told me about an encounter he had while the Capp-Fisher feud was transpiring. Lazarus and his then-wife used to finish up the week by having a drink together in a bar on Fifth Avenue. And for a couple of weeks, they noticed a man at a nearby table who seemed to be eavesdropping on their conversation. Finally, one Friday, the man got up and came over to their table.

“Pardon me,” he said, “but I couldn’t help overhearing you mention Al Capp.”

“Yes?” said Mell.

“Do you know Al Capp?” asked the man. “Do you see him often?”

“Yes”

“Well,” said the stranger, “my name is Ham Fisher, and I wonder if you’d give him a message from me. Tell him I’d like to be friends again. Tell him he’s won. All I want is that we should be friends again.”

The next time he saw Al Capp, Lazarus reported the incident—to Al’s giddy delight. "He seemed pleased,” Mell told me, “and amused. But he didn’t dwell on it with me, nor did we ever discuss it again.”

VI. “I Remember Monster”

FISHER’S QUARREL WITH HIS ONE-TIME ASSISTANT continued and became an obsession, and that, coupled to his own oft-trumpeted self-importance, made Fisher a colossal boor. It also made him the perfect target for any number of practical jokes staged by other cartoonists, most of whom by this time had little regard for him.

Once, as reported by Bob Dunn in Cartoonist Profiles #40 (December 1978), when Fisher threatened to derail a charity luncheon at “21” from its purpose by usurping the agenda to attack Capp, one of the group slipped out and recruited a comely young woman to deliver Fisher’s comeuppance.

Unannounced, she walked into the third-floor private room and made straight for Fisher. She was good-looking enough to stop conversation; everyone watched her progress in silence. Giving Fisher a brilliant smile, she handed him a piece of blank paper and asked for his autograph. Almost certainly dazzled by her beauty and flattered by the obvious adoration of such a gorgeous creature and gratified by thoughts of the envy her admiration must inspire in those around him, Fisher drew the face of his famous character and signed it “with all good wishes from Joe Palooka and Ham Fisher.”

The girl took the paper and stared at it in frowning perplexity. Then, tearing the paper twice and dropping the pieces on the floor, she exclaimed, “You’re not Al Capp? I wanted Al Capp’s autograph!” She turned on her heels and strode away.

The room exploded. Fisher turned white in rage and embarrassment. No man can take a joke about his obsession.

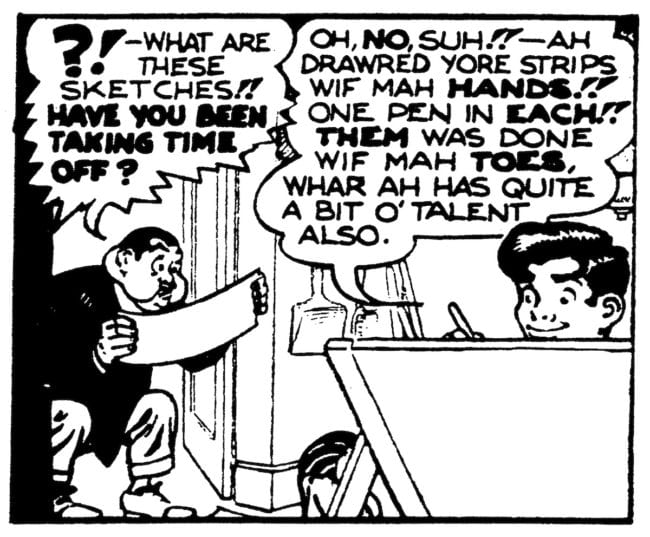

Knowing Fisher employed assistants to draw Joe Palooka, cartoonists circulated the rumor that Fisher couldn’t draw at all. Ironically, Capp’s practice in producing Li’l Abner was very similar to Fisher’s with Palooka.

Capp had help drawing the strip from the start. His wife Catherine did the backgrounds — landscapes and trees — and some inking. Capp soon employed Moe Leff for a time, and then Andy Amato, followed by Walter Johnson, and Harvey Curtis. Amato was with Capp the longest — from near the beginning until the end. Amato penciled the strip — or, perhaps in the early years, tightened Capp’s pencils for as long as Capp roughed out the panels; Johnson did a lot of the inking, and Curtis did the lettering and filled in the blacks. Like Fisher, Capp drew the faces of his principals, but no one spread rumors of Capp’s inability to draw.

Other assistants came and went over the years, coming from or going to a fame of their own — Bob Lubbers for the longest (reportedly 1958-1977); Frank Frazetta on Sundays (1953-1961); and for shorter periods, Stan Drake, Creig Flessel, Tex Blaisdell, Larry May, and others. But Amato, Johnson, and Curtis also helped write the strip. Capp concocted plots in conference with them.

Describing what he called “the ensemble effort” of writing the strip in Al Capp Remembered, Elliott Caplin said: “The story sessions were often romps through the wildest fantasies of the four men. Each brought to the studio his own prodigal dreams and tried to flesh out his urges, prejudices and hang-ups in an Abner continuity. ‘How about’ was the kick-off for a story conference. ‘How about this guy who’s never been to a city bigger than like a couple of hundred people ... and looking for a girl whose picture he’s seen on the cover of — no, maybe not a magazine, but a poster. ...’

“The four men would explore and dissect the story line,” Elliott continued. “A hundred variations were discussed and discarded. Time would pass, and eventually a continuity was fashioned that could be a hundred years away from the initial concept. Alfred appreciated and rewarded his staff. He especially valued Andy Amato for his unorthodox and undisciplined flights into absolute insanity. Andy felt free to soar, knowing that Alfred would exercise his superb story sense in fashioning the final drawn version of Andy’s frequent bouts with paranoia.”

In a November 1950 cover story on Capp, Time reported that Amato and Johnson were paid 10 percent of Capp’s profits, about $30,000 a year apiece. A few years before, E.J. Kahn, Jr. in his profile of Capp in The New Yorker claimed the assistants’ percentage was 15 percent and that it amounted to “around $35,000 a year between them,” high pay but Capp said it made his life easier: “I don’t like to have to spend a lot of time in the company of people who can’t sympathize with me when I complain about my income taxes,” he said. Although in these later years, the assistants were named in articles about Li’l Abner, I have only once encountered Capp speaking highly of them without at the same time lacing his comments with humorous jibes or satirical asides.

Rick Marschall’s interview with Capp in Cartoonist Profiles #37 was conducted shortly after the cartoonist’s retirement from the strip in 1977, and Capp said about his assistants: “When I say ‘I,’ I mean these other guys equally with me. I’m the guy who signed the strip, and I made up our minds about what we would do, but they had just as much effect on the strip as I.” Generous applause, but a little late in coming compared to Fisher’s effusive published comments about his assistants as early as 1948.

In 1950, the Fisher-Capp feud boiled over. In the April issue of Atlantic Monthly was an article by Al Capp, purporting to explain the inspiration for the more villainous characters in Li’l Abner — “those unsanitary, uncouth, unregenerate, unspeakable apes, fiends, and human horrors whose lechery, treachery, and skulduggery make the golden goodness of the Yokums shine even more brightly by contrast.” Capp called it “I Remember Monster”, and although he never mentioned Ham Fisher by name, it was clear to anyone familiar with his well-publicized professional history that the monster was Fisher, his one-time employer. With his customary high-flying hyperbole, Capp claimed he didn’t have to invent any of those unsavory varmints that so invigorated his strip:

The truth is I don’t think ’em up. I was lucky enough to know them — all of them — and what was even luckier, all in the person of one man. One veritable gold mine of human swinishness. It was my privilege, as a boy, to be associated with a certain treasure-trove of lousiness, who, in the normal course of each day of his life, managed to be, in dazzling succession, every conceivable kind of heel. It was an advantage few young cartoonists have enjoyed — or could survive. I owe all my success to him. From my study of this one li’l man, I have been able to create an entire gallery of horrors. For instance, when I must create a character who is the ultimate in cheapness, I don’t, like less fortunate cartoonists, have to rack my brain wondering what real bottom-of-the-barrel cheapness is like. I saw the classic of ‘em all. Better than that, I was the victim of it.

Capp went on for the rest of his four-page essay to retail extremely unflattering anecdotes about the man he referred to only as his “Benefactor.”

Goaded on, doubtless, by such humiliations and by his continued failure to get anyone to take him seriously on either hillbillies or Capp’s theft of them, Fisher resorted to a peculiarly unsavory way of striking back at his nemesis. In its 1950 cover story on Capp, Time said that Fisher had certain panels of Li’l Abner enlarged and reprinted, then, circling selected graphic details in red, he distributed them to the editors of newspapers carrying the strip. Alleging that the highlighted details were subliminal pornography designed to undermine the youth of the nation, he urged editors to drop Capp’s strip.

Capp’s article in The Atlantic Monthly and Fisher’s smear campaign brought matters to a head. The feud had become too public. It was unseemly and disgraceful that the creators of two of the most popular comic strips in the country should be so viciously tearing away at each other. Their respective syndicates, fearing they’d lose papers as a result of the fight, called for a truce, and a peace treaty was negotiated by proxies in August 1950. Unhappily, the story did not end then.