Previously, the introduction and part two of our story.

III. Al and Abner

AL CAPP WAS BORN ALFRED GERALD CAPLIN on September 28, 1909, in New Haven, Conn., of East European Jewish heritage. His parents had come from Latvia to New Haven in the 1880s. Alfred was the eldest son of Otto Caplin, a chronically unsuccessful salesman, and Matilda Davidson, a woman with a fierce survivor instinct who shepherded her family through a persistently penurious existence. William Furlong explains how (in The Saturday Evening Post, Winter 1971): “She tutored her children in the techniques of living on nothing at all — wheedling stale bread from bakers, refusing to deal with grocers who wouldn’t hire one of her sons, leading the children on rubbish raids that might turn up a few usable items of clothing or even an unused piece of coal.” Whenever she ran out of rent money, the family moved, first to Bridgeport and then from one rented house to another in Boston.

As a child, Capp (the pen name he adopted as his legal name in 1949) had been a prodigious reader. He’d read Joseph Conrad, Anthony Trollope, Charles Dickens, and all of Shakespeare. And he’d read all of George Bernard Shaw — at the age of 13. He’d done a lot of reading during his youth because he couldn’t be physically active. He’d lost his left leg when he was almost 9. One hot August afternoon in 1918, he’d hopped a horse-drawn ice wagon to pinch a shard of ice. A trolley car was only a few feet behind the ice wagon when Capp jumped off, stumbled and fell under the streetcar’s wheels. “When they took me to the hospital,” he recalled, “I had no identification and so they roused me and I looked at the leg, and it was a mess — like scrambled eggs. There was just nothing that you could call a ‘leg’ left of it.” They amputated above the knee.

After that, Capp hobbled along on crutches until he was fitted with an artificial leg. But his father, working mostly as a traveling salesman, couldn’t afford to replace the leg often enough to keep pace with his son’s growth. For most of his youth, Capp’s wooden leg was too short, and he’d never learned to walk properly. He limped more pronouncedly than many people with artificial limbs. But he didn’t complain; nor did he want sympathy.

When he wasn’t reading as a kid, Capp was drawing. His father, who had trained to be a lawyer, was something of an artist, and his drawings for his family’s amusement inspired his son.

“My father’s real talent was drawing,” Capp said in Furlong’s article. “He was a most naturally gifted comic artist. I grew up watching my father do comic strips on brown paper bags with my mother and himself as the two principal characters. He always triumphed over her in those strips. But only in them. Never in real life.”

When he was 12, Capp read about Bud Fisher making $4,000 a week drawing Mutt and Jeff, and he decided forthwith to become a cartoonist. And in Brooklyn, to which the family moved for six months about that time, he sold his first drawings. In Cartoonist Profiles #48 (December 1980), his brother Elliott tells the story of Al’s career in school:

They put him in a class of retarded children because he wasn’t normal — he was a “cripple” in the school’s parlance; he had only one leg. Of course, it was a brutal class with a bunch of real young criminals, and the only way he could survive in this terrible, physically threatening atmosphere, was through his talent: he drew pictures. So instead of beating him up, they began to admire him and request drawings. Mostly they wanted pictures of their teacher — nude! So he survived because he could draw Miss Mendelsohn nude.

Capp charged 25¢ a piece for the pictures. But when he retold the story in his memoirs, My Well-Balanced Life on a Wooden Leg, he left out the part about being in a remedial class. In his memory, the entire student body of P.S. 62 in the Brownsville “(or Murder, Inc.)” section of Brooklyn consisted of “subnormals, petty thieves, rapists and thugs.” Miss Mendelsohn became Miss Mandelbaum, and because she taught drawing, she recognized young Capp’s talent “and showed great interest in my work, coming in every day, bending over my desk to watch me draw and coaching me as I went along. My classmates showed a great interest in Miss Mandelbaum’s coaching, mainly because of what happened to her neckline when she bent over to coach me.”

One day when Miss Mandelbaum realized what kinds of pictures her protégé was making of her, Capp said, “she screamed a terrible scream of anguish and betrayal ... and ran out of the room. She never came back. My father’s business [in Brooklyn] failed, we moved back to Massachusetts, and my career as a professional artist didn’t get going again for ten years.” In Capp’s retelling, he was drawing Miss Mendelbaum in a one-piece bathing suit, not in the nude.

As a teenager, Capp often absented himself from the family hearth to wander off into unexplored climes. “At 13 or 14,” his brother Elliott wrote in the 1980 Cartoonist Profiles article, “he’d take off with his friends for Atlantic City or for Vermont.” One summer, after telling his mother he was going out to get a pack of cigarettes, he disappeared for two weeks. Thumbing a ride to the store, Al and a friend stopped a car the driver of which said he was going to Memphis, Tenn. The boys promptly changed their plans: They, too, they said, were going to Memphis. And they did. By a less than direct route.

In Memphis, they stayed with Al’s Uncle George Baccarat, an orthodox rabbi, for a few days, until, as Elliott described it in his Al Capp Remembered, they managed to outrage the relatives with “their quaint toilet habits and relentless pursuit of the daughters of Uncle George’s parishioners.”

En route to Memphis, the youths passed through the Cumberland Mountains, and Al encountered his first hillbillies, an experience he later said inspired his creation of Li’l Abner, exaggerating the simplicity of the hill folk into a burlesque masterpiece. The hillbilly encounter, Elliott delicately implied, was part of the Li’l Abner “mythology”: “After the strip had become a success, Alfred felt that it needed a historian as the Trojan War needed a historian. And Alfred become his own Homer.”

Following an incomplete high-school career distinguished mostly by his truancy, Capp entered a succession of art schools, including the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the Boston Museum School of Fine Arts, and the Designers Art School, where he met Catherine Wingate Cameron, whom he married in 1932. Explaining the litany of art schools, Capp joked that since he couldn’t afford tuition, he left them one after the other when the bills came due.

At the end of this parade of art courses, Capp decided to assault the citadel of professional cartooning: He went to New York, capital of cartooning in the U.S. He eked out a living for a while by selling advertising cartoons, but he also prevailed upon another uncle, Harry Resnick, an agent of sorts, to help him find something better. Resnick called the Associated Press and asked if someone would look at his nephew’s drawings. The editor of AP’s feature service, Wilson Hicks, looked, and a short while later, he called Capp and gave him Colonel Gilfeather, a panel-cartoon continuity that had been staggering along under the rather clumsy pen of Dick Dorgan. Dorgan was the younger brother of the legendary panel cartoonist “TAD” (Thomas Aloysious Dorgan) who had made comic capital from his “low life connections.”

Capp came to New York in the early spring of 1932 and confronted Gilfeather. It was not a felicitous encounter. His stewardship on the feature was, as it proved, a doomed undertaking. Capp was struggling to master his craft, and he had to start by imitating Dorgan. The idea was to make the shift gradually from Dorgan’s style to his own. But Capp, as yet, barely had a style. He admired the pen-work of Phil May, a British cartoonist of the late 19th century whose economy of line anticipated modern cartoon graphic technique by thirty years. Capp had seen a book of his cartoons in the library. Capp scorned Dorgan’s work, and he hated Colonel Gilfeather. Nonetheless, he slaved over it. In an attempt to whip up his interest in the feature, he shifted the focus from Colonel Gilfeather to his younger brother and retitled the cartoon Mister Gilfeather. Gilfeather the Younger was as much a blowhard as his brother, but rather than inventing moneymaking schemes, he spent most of his energies chasing girls, enjoying a somewhat happier prospect than the Colonel’s.

Capp lived in a succession of what he called “airless rat-hole rooms” in Greenwich Village and stalked the streets every day, reading menus in the windows of restaurants until he found a place he could afford. He was paid $52 a week for Gilfeather, enough to live on in New York, but he sent part of it to his new bride, Catherine. She was living with her parents in Amesbury, Mass., because he had too little money to afford an apartment for them both. Capp kept irregular hours at the AP office, and when he came in, it was usually in the afternoon, and he worked into the evening. That’s when he met Milton Caniff, and the two formed a lifelong friendship.

Caniff had just arrived in New York from Columbus, Ohio, and he worked evenings, too, and he got to know Capp very well. “He was a kind of sad sack in those days,” Caniff told me. “He could be very difficult if he didn’t like you. Not a charming person unless he chose to be.” But Milton was charming and sympathetic. He made a good listener.

“In the daytime,” Caniff reflected, “we would probably have never spoken a word to each other, but at night we talked. In an empty office like that, you talk about things you wouldn’t talk about when other people were there. He and I got along fine right off the bat. I realized he was struggling — to do Gilfeather, to make it.”

By late summer, Capp had had enough. Faced with incompatible material, separated from his new wife and struggling to subsist from day to day, Capp doubtless felt the job wasn’t worth the strain. Whatever the case, he quit the AP and went back to Boston, where he studied at the Museum of Fine Arts for several months before returning to give New York another try.

CAPP RETURNED TO THE BIG APPLE with six bucks in his pocket and had no luck, so when Fisher stopped him that spring day on Eighth Avenue near Columbus Circle (or maybe it was on 42nd Street just outside the Daily News building; legends differ) and offered him a job, Capp eagerly accepted. For several years thereafter, both cartoonists told the same story about their initial meeting, but by 1950, when the feud was bubbling to a boil, Fisher and Capp each had their own version of that encounter. Both versions were rehearsed in Maclean’s Magazine (April 1, 1950). Here’s Fisher’s version:

I was driving with my sister Lois when I saw a fellow carrying a roll of paper along the street. He looked unkempt and was limping. I pulled over and said, “What kind of drawings have you in there, buddy?”

“How’d you know they’re drawings?”

“I work at the Mirror and see lots of comic strips come in wrapped in that kind of paper,” I said.

“Nobody’ll buy my drawings. I’m headed for the river,” he said.

I said, “Hop in and we’ll go to my house for lunch.”

His name was Al Capp. I didn’t tell him mine. I asked him, “What’s your favorite strip?” To my delight, he said, “Joe Palooka.”

Capp saw on my wall a portrait of me by James Montgomery Flagg, inscribed “To Ham.” Capp said: “Why, it’s you. You’re Ham Fisher.”

He begged me for a job. I had an assistant, and I couldn’t see how I could afford another one. But I took pity on him and gave him a job lettering and inking-in. Many months later, I was going on a week’s vacation. Capp came up just as I was leaving and demanded a $50-a-week raise, and sneered that I wouldn’t be able to go away if he refused to work. I blew up. I fired him and took the work with me.

When I returned, Capp called incessantly, begging for his job back. I got him a job with United Feature Syndicate where he started a hillbilly strip called Li’l Abner. It was so similar to the hillbillies I had originated in Joe Palooka that I protested to the syndicate. Capp apologized to me and promised to change the characters. He has never fully done so. He now claims he originated the cartoon hillbillies. Despite his present-day claim, Mr. Capp has stated several times earlier in interviews that I taught him what he knows.”

Capp, to whom James Edgar, the writer of the Maclean’s piece, showed Ham’s story, made a few corrections:

Fisher’s story about picking me up in his car, after accosting me in a New York street, is true. Fisher’s wrong when he says I was hired to “letter” for him. I was an artist — good enough the year before to do a syndicated cartoon for the Associated Press. Fisher would have been a highly impractical man to restrict a competent artist and writer to simple lettering.

Fisher cannot draw at all, except for a few simple chalktalk tricks, so when he says he “took the drawings with him,” it is a pathetic claim. I never told him Joe Palooka was my favorite strip. It’s the kind of strip I deplore, a glorification of punches and brutishness.

I was making $19 a week, later $22, while working for Fisher. For the period I was employed by Fisher, I drew in their entirety all his Sunday pages, created all the characters therein, and wrote every line. The time he went away was for six weeks, not one. He didn’t leave me any money when he went, and we had to live on what my wife was making.

I had time on my hands and whipped up Li’l Abner and sold the cartoon to United Feature Syndicate. The part where he says he got me a job with United is the part I am most bitter about. When he found out I was with United, he threatened to sue. For three years, he tried everything to get me fired.

To which Fisher responded:

I never had six weeks’ vacation in my life. When Capp worked for me, I never had more than a week. I’m amazed at Capp’s effrontery. His entire statement is false. As for suing United — that’s a gross exaggeration of a complaint I made when I learned he was spreading the lie that he had created some of the Palooka sequences. United Feature apologized to me.

Fisher’s self-aggrandizing embroideries betray his version as somewhat fictional — his generously offering lunch to an impoverished stranger, Capp’s naming Joe Palooka his favorite strip, Fisher’s taking pity on the poor lad and creating a job for him. Later in the article, Edgar quotes Fisher claiming to have “started the trend of comic strips away from vaudeville skits toward continuous adventure stories”; in fact, by 1930, Roy Crane at Wash Tubbs was well into telling adventure stories that continued from day to day. Fisher also told Edgar that he “innovated the use of current events as story backgrounds”; I suspect Caniff was a little ahead of Fisher with Terry and the Pirates set in China.

According to the Capp clan’s version of the events of his employment on Joe Palooka, Fisher, after a few months, went off to London on a trip with Flagg — just disappeared, Capp said. Interviewed by Carol Oppenheim at the Chicago Tribune on the occasion of his retiring from Li’l Abner in November 1977, Capp said, while Fisher was gone, the syndicate phoned and asked for four more weeks of the Sunday strip.

“Out of loyalty,” Capp said, “I didn’t mention Fisher’d vanished. I wrote the strip myself. But I wasn’t going to have anything to do with that stupid prizefighter; so I put in my own characters — the hillbillies. They were hilarious. But when Fisher came back, he fired me.”

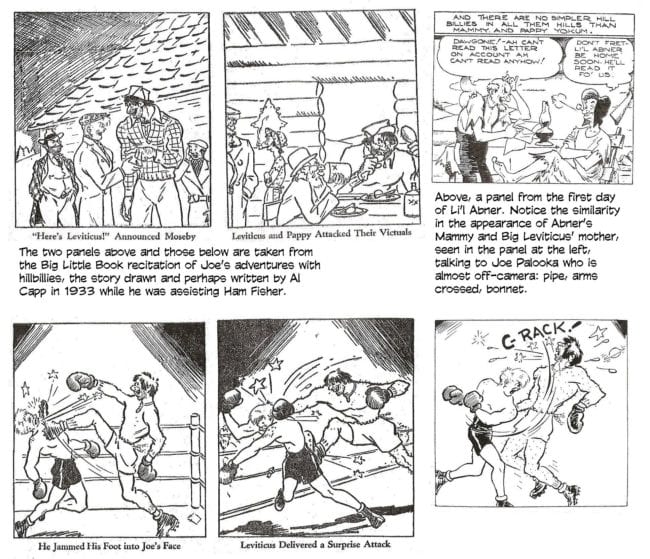

Capp maintained that he’d conjured up the hillbillies from his memory of those he’d seen in his youth on that fabled trip through the South; he took Joe Palooka into the hills and staged a match between the champ and the meanest of the hillbillies, a ribaldly uncouth character named Big Leviticus. This episode became the bone of contention between Fisher and Capp, giving rise eventually to the most scandalous incident in the profession’s short history.

In the Fisher version of these events, Fisher had the idea for Big Leviticus and wrote the story, leaving the illustration of it to Capp. In other words, he followed his usual practice in producing the strip.

The Big Leviticus story ran on Sundays in November 1933. Capp quit working for Fisher soon thereafter. He’d been working up a comic-strip idea at home in the evenings, and by late winter, he was taking samples around to syndicates. In an interview with Rick Marschall in Cartoonist Profiles no. 37 (March 1978), Capp related his selling adventure:

I brought the Abner samples up to King Features, and they offered me 250 bucks a week, which is the equivalent of a thousand — even more — today. But the big guy there — [Joe] Connolly — said, “Great strip, great art, yes sir. A couple of things, though. That Abner’s an idiot. Make him a nice kid with some saddle-stripe shoes on him. And Daisy Mae’s pretty, but how about some pretty clothes? As a matter of fact, why not forget the mountain bit and move them all to New Jersey; and that Mammy — she’s got to go. You need a sweet, white-haired lady.”

Well, I thought all about it, and I realized that [he was describing] Polly and Her Pals. But I had 250 bucks a week, didn’t I? Well, I was pretty sick about it. I walked up to United Feature — [Monte] Bourjaily was the head of it then — and they looked at it, showed it to Colin Miller and the other salesmen, were amazed by it and wanted to take it out just as it was. They offered me 50 bucks a week — which was the lowest — and I grabbed it and forgot King Features because I was now able to do my own strip exactly as I wanted to. Later on, of course, they paid me $5,000 a week because there was no way they could get out of it.

Capp was ever after unhappy with his relationship with United. He was continually fighting for more editorial freedom. In 1947, he sued the syndicate for $14 million, alleging breach of contract, but settled out of court for an undisclosed amount. And in 1964, just after he acquired ownership of the strip, he took Li’l Abner to another syndicate, the Chicago Tribune-Daily News, where he negotiated a better deal.

Marschall continues his recounting of the story of Li’l Abner’s sale, saying Capp had told the story thousands of times. “Capp’s late Uncle Harry related to me that the problem at King Features simply was that they took too long to respond. I’m sure the truth is in both recollections. Capp’s brother Elliott told me that Al’s straight biography and his embellished versions of it are equally fascinating.”

Capp, a professional storyteller, knew a good story when he heard one, and to such a storyteller as he, a good story was a great improvement upon whatever mundane facts might be lying around. He often laminated his autobiographical comments with variations that improved the story or supplied a satisfying punch line.

As a matter of documented history, in June 1934, Capp signed a contract with United Feature, and Li’l Abner started in eight newspapers on Aug. 13 (by Christmas, according to some accounts, it was in 400 papers; eventually, 900-1,000). Abner’s debut was less than a year after the Big Leviticus episode in Joe Palooka. Judging from the sequence of events, Fisher assumed that Capp had found his inspiration for a comic strip about hillbillies in the Big Leviticus story.

Catherine Capp, who had joined her husband in New York once he was on Fisher’s payroll, wrote an introduction to Volume One of the Kitchen Sink Press Li’l Abner reprint series in which she remembers inspiration striking in another way:

One night while Al was working for Fisher, we went to a vaudeville theater in Columbus Circle. One of the performances was a hillbilly act. A group of four or five singers/musicians/comedians were playing fiddles and Jews harps and doing a little soft shoe up on stage. They stood in a very wooden way with expressionless deadpan faces and talked in monotones, with Southern accents. We thought they were just hilarious. We walked back to the apartment that evening, becoming more and more excited with the idea of a hillbilly comic strip. Something like it had always been in the back of Al’s mind, ever since he had thumbed his way through the Southern hills as a teenager, but that vaudeville act seemed to crystalize it for him. ...

Al and I conferred about the characters while he was drawing his samples. I’ll take credit for naming Daisy Mae and Pansy Yokum, although contrary to popular belief, I was not the model for Daisy. The closest I came to being a model in the strip happened later when Al used my hair for Moonbeam McSwine.

It wasn’t just her hair. Capp once said that Moonbeam was inspired by Catherine, because she, disliking big city life, spent her time on the Capp farm, out in the country — among the cows and pigs, like Moonbeam who preferred livestock and hog wallow to social high life. (Or maybe Capp was merely improving upon a good story by giving it a fictional punch line.) Indirectly, Catherine also named the strip’s protagonist: “‘Abner,’” she wrote, “was what we had nicknamed the baby when I was pregnant; it’s what we called Julie before she was born.” For Abner’s appearance, Capp claimed to be inspired by Henry Fonda, an unlikely contention on the face of it: Fonda was scarcely a national figure at the time; his first movie was in 1935, at least months after Li’l Abner was launched. But it was Fonda’s character Dave Tollier in “The Trail of the Lonesome Pine” in 1936, Capp said, that gave him the “right look” for Abner.

Although it’s not clear from Catherine’s account whether the young couple witnessed the vaudeville act before or after the creation of the Big Leviticus episode, the hillbillies on stage undoubtedly excited Capp’s imagination, leading, eventually, to a strip featuring hillbillies as the central characters.

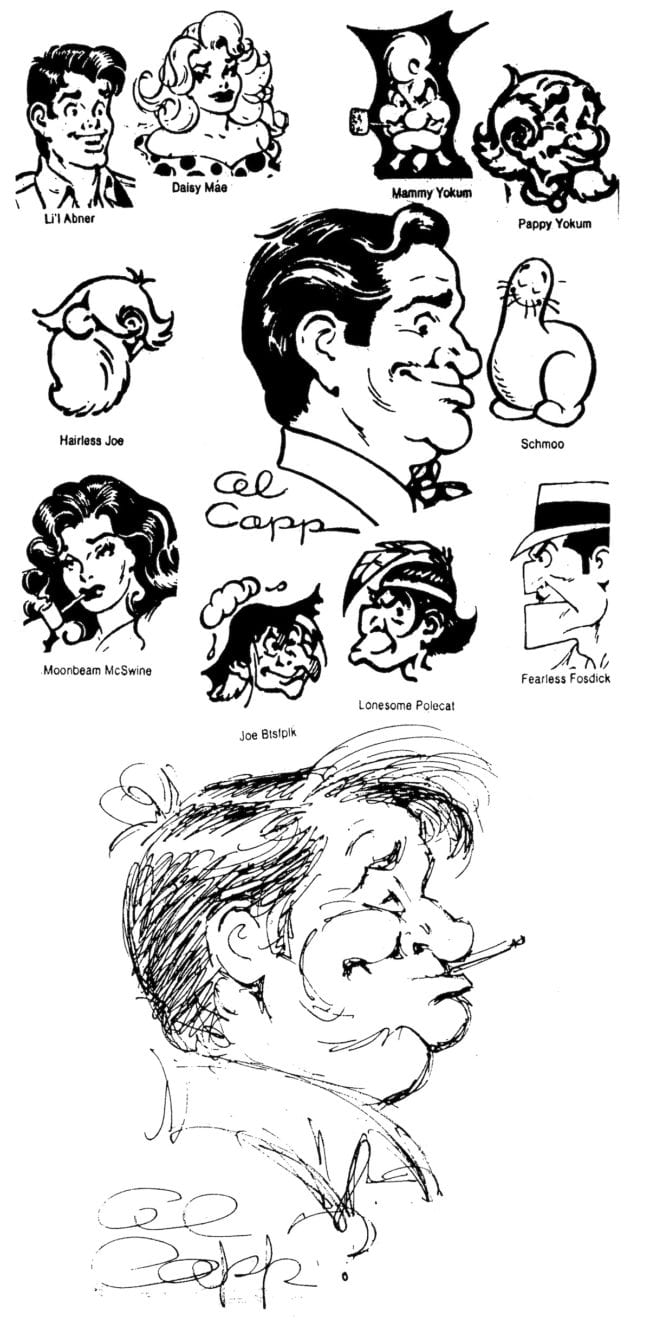

Li’l Abner Yokum is a red-blooded 19-year-old with the mature physique of a body-builder and the mind of an infant who lives contentedly with his diminutive mother, Pansy, the pipe-smoking matriarch of the family, and his simpleton Pappy in poverty-stricken Dogpatch, a backwoods community perched precariously on the side of Onnecessary Mountain (or, sometimes, languishing in its shadow). “Yokum,” supposedly a combination of “yokel” and “hokum,” was actually phonetic Hebrew, Capp once said — “joachim” means “God’s determination.”

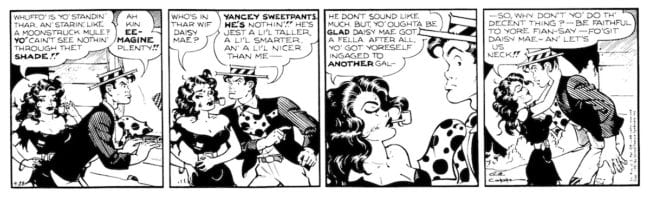

The only cloud in young Abner’s idyllic, every day, blue sky is Daisy Mae Scragg, a skimpily clad blonde mountain houri who is forever pursuing him with (“gulp”) matrimony in mind; Li’l Abner, too stupid to realize even that he loves her, shuns the nuptial bond as well as her embrace, imagining them as somehow unmanly. Daisy Mae drags him before Marryin’ Sam at least once a year, but the ceremony is invariably nullified by some groaning plot contrivance; when Capp finally married them for good, he’d enjoyed eighteen years of dangling the prospect before his readers. Li’l Abner’s shyness with women and his studied reluctance to recognize sexuality at all is a satire on American Puritanism: If things were as Puritans imagined, Abner wouldn’t be funny. But he is funny, revealing that we recognize at once how absurd the asexual repressiveness is.

Capp’s Candide, Li’l Abner is fated to wander often into a threatening outside world, where he encounters civilization — politicians and plutocrats, mad scientists and cunning swindlers, mountebanks, bunglers and love-starved maidens. By this device, Capp contrasts Li’l Abner’s country simplicity against society’s sophistication — or, more symbolically, his innocence against its decadence, his purity against its corruption. The comedy arises from this clash of cultures: We laugh to see Abner’s simple-minded struggle against the forces of civilization that seem to him so inexplicable, so utterly without practical foundation, and we roar with satisfaction when he eventually triumphs over the twisted insincerity of “high society,” his innocence, his ignorance, intact. Throughout, the humor is circumstantial, arising from the preposterousness of Abner’s predicament and his simplicity in dealing with it, rather than from carefully structured jokes. Capp’s effort was not so much to end his daily strips with punch lines, as it was to finish with extravagant cliffhangers.

It was man and his society that comprised Capp’s primary targets. As a satirist, he ridiculed the pretensions and foibles of humanity — greed, bigotry, egotism, selfishness, vaulting ambition. All of man’s baser instincts, which the cartoonist saw manifest in many otherwise socially acceptable guises, were his targets. Li’l Abner is the perfect foil in this enterprise: Naive and unpretentious (and, not to gloss the matter, just plain stupid), Li’l Abner believes in all the idealistic preachments of his fellow man — and is therefore the ideal victim for their practices (which invariably fall far short of their noble utterances). He is both champion and fall guy.

Capp’s vehicle was burlesque, a mode of satirical comment that allows no fine gray shadings — only stark blacks and whites. Painted only in these hues, the world he revealed was divided simply into the Good (the Yokums) and the Bad (almost everybody else). And Capp’s tactic was the shotgun: a single blast that obliterated his target without fuss or, usually, finesse.

His criticism of American foreign aid, for instance, was contained in the creation of Lower Slobbovia, a completely snowbound fifth-rate country whose inhabitants, up to their chins in hostile environment, have no visible means of support. Their favorite dish is “raw polar bear and vice versa.” Speaking in a strange-sounding language fraught with not-so-faint echoes of Yiddish, the natives survive entirely on the hope that the United States will provide foreign aid. Beyond the joke of the Slobbovians’ helplessness and laziness and their abject poverty and perpetual starvation, the satire goes nowhere. Having taken his shot, Capp seemingly runs out of ammunition.

In his interview with Marschall, Capp admitted that he was “so embarrassed by his endings that I try to forget them.” Many of his endings are thoroughly forgettable, but sometimes, often enough, Capp excelled.

Abner’s first adventure is a happily contrived satire ending with sting enough. In the first sixteen months of his life, Li’l Abner, the quintessential country hick, spends more time in New York City than in the hills of his home in Dogpatch. And in that circumstance is the flywheel of the strip’s satirical dynamic.

At the very point of our meeting Li’l Abner and his hillbilly entourage, Abner gets a letter from his rich Aunt Bessie, who invites him to spend time with her in New York society in order to acquire polish and to enjoy “the advantages of wealth and luxury.” Abner goes to the big city and stays there for the next four months.

In one episode of that sojourn, a phony baron (actually, a penniless confidence man) with an impressive beard goes after Aunt Bessie’s hand in marriage, his eye firmly focused on her fortune. Li’l Abner finds out that the baron’s intentions are less than honorable, but he’s helpless to do anything about it. His first instinct is to “smack the baron aroun’ somewhat an’ throw him outa th’ house,” but he recognizes that this behavior isn’t gentlemanly, and since his Mammy has sent him to Aunt Bessie to learn to be a gentleman, he dutifully refrains from taking this course of action.

And when he decides simply to go to Aunt Bessie and tell her what a lout the baron is, he learns that his aunt is in love. Rather than destroy her happiness, he says nothing to her about the mercenary intentions of her lover and soon-to-be-husband. It seems that Bessie is doomed to be duped.

At the last moment — just before the wedding — Abner remembers a smattering of his Mammy’s wisdom: “Anyone which is a skunk looks like one.” Putting this axiom into practice, he gets a razor and forcibly gives the phony baron a shave. Without his imposing chin whiskers, the con-man is revealed as a nearly chinless simp. Bessie is no longer impressed, and she calls off the wedding.

The story is an insightful template for Capp satire, a handy guide to his method. Again and again over the next decades, he would perform this operation — stripping the pretensions away, revealing society (all civilization perhaps) as mostly artificial, often shallow and self-serving, usually avaricious, and, ultimately, inhumane and therefore without meaning. We laughed, but underneath the strip’s comedy, it wasn’t funny.

In his book America’s Great Comic Strip Artists, Marschall found a determinedly misanthropic subtext in the satire of Li’l Abner:

Capp was calling society absurd, not just silly; human nature not simply misguided, but irredeemably and irreducibly corrupt. Unlike any other strip, and indeed unlike many other pieces of literature, Li’l Abner was more than a satire of the human condition. It was a commentary on human nature itself.

In the story of the shmoo, Capp created what was probably the most sustained satire in the strip: This sequence had a beginning and an end, and all along the way, it supported and reinforced the satire. The shmoo, for those who missed it, is a soft, squishy-looking bowling-pin of a cuddly critter with two legs and feet but no arms, two eyes and one mouth but no nose, whose whole purpose in life is to make others happy, which it does by magically producing all sorts of foodstuffs and other useful items. They lay eggs “at the slightest excuse” and give milk and cheesecake; as for meat — broiled they make the finest steaks; fried, yummy chicken. They drop dead out of sheer ecstasy if you look at them hungrily. And there’s no waste: their hide makes the finest leather or cloth (depending upon how thick you slice it), their eyes make suspender buttons, and their whiskers, toothpicks. Moreover, they are available in endless supply, because they breed more rapidly than fruit flies.

Li’l Abner stumbles onto shmoos in August 1948 and the world is subsequently on the brink of changing forever: Once shmoos are loose in so-called civilization, humanity loses the motivation to go to war and to engage in every sort of capitalistic enterprise. Why bother? Shmoos provide everything one needs. And for that very reason, in Capp’s satirically warped mind, they had to be destroyed wholesale. Otherwise, they would “corrupt” society, demolishing the very things upon which civilization is founded — namely, greed and need. The character was such a happy satirical conception, so cute, and so popular (and so successfully merchandised), that Capp brought it back briefly in 1959, but without the merchandising success of its inaugural appearance.

Because he attacked the conventions of modern civilized society and because the most conspicuous upholders of those values were the wealthy and powerful members of the establishment and because America’s establishment was mostly political conservatives, most of the icons Capp smashed so exultantly were initially those of the political Right. Consequently, Capp was initially popular with liberals.

A protean talent, Capp invented a host of memorable characters and introduced a number of cultural epiphenomena. His cast is populated with Dickensian eccentrics: the denizens of Dogpatch — Lonesome Polecat, the local Native American, and his partner in brewing Kickapoo Joy Juice, a hirsute giant named Hairless Joe; Earthquake McGoon, the neighborhood strongman; Barney Barnsmell, the “outside man” at the Skonk Works (the only indigenous industry), and his brother, Big Barnsmell, the “inside man”; the Wolf Gal, a rapacious wild girl; Senator Jack S. Phogbound; the voluptuous Moonbeam McSwine, who likes pigs better than people; and in the world beyond Dogpatch — Joe Btfsplk, a jinx whose influence was symbolized by the small raincloud that hovered always over his head; Evil-eye Fleegle, whose glance could fell an ox; Lena the Hyena, a woman so ugly Capp wouldn’t draw her; and Appassionata van Climax, an outrageously flagrant sex symbol (about which, Capp reported in surprise, no editor ever objected).Perhaps the most famous of his secondary characters is the one that threatened at times to take over the strip: Introduced in August 1942, Fearless Fosdick is a razor-jawed parody of another comic-strip character, Dick Tracy.

The most notorious of Capp’s contributions to popular culture is Sadie Hawkins Day, an annual November footrace (the precise date of which varies from source to source) in which the unmarried women of Dogpatch pursue unmarried men across the countryside like so many hounds after the hare, marrying those whom they catch.

Next: The Hillbilly Feud