Last year saw Dash Shaw release some of his most interesting comics to date. Two issues of his series Cosplayers slipped out quietly into stores by mid-summer, each offering a playful, character-focused look at different kinds of subcultures along with a bouquet of subtle formal satisfactions. And after those came Doctors, a carefully structured work about a group of modern doctors who create and operate a machine that brings people back from the dead. Like the earlier titles, it seems humanistic but is also classically speculative, posing scenarios and asking questions with no clear answers.

I was happy, then, that Dash agreed to the following interview. At his request we corresponded over email, tweaking the full transcript afterwards, with one another's approval. I've always liked Dash's writing both in and out of his comics—so I hope you'll enjoy what follows.

George Elkind: You wrote on your blog that Doctors "was built one page at a time — each page is a single scene and a single solid color in the book. I could switch scenes around, cut out pages, and read the book in entirely different page orders." After reading this, the book seems surprisingly cohesive, unified by what seems an almost flat—or affectless—tone, brought out by those solid-colored pages. How much did you know about what Doctors would become early on, or from the outset? That sense of unity makes me think you might have began with other parameters for the book, even if they later fell away. Is that accurate?

Dash Shaw: I had a system in place for improvisation, which is why the book appears unified (if it does). Since each Doctors page is a separate unit, I could insert a page early in the book to set up something later. I collaged the book together.

Sometime around 2010, I had a thought "comics are a collage medium -- they're collages that you can read." Everything I've done since then has been extrapolating from that idea in different ways. With Doctors, I started with clips from different sources, mostly old romance comics. The first page I drew was the diver page. I clipped that diver from an old romance comic. I loved how stiff the drawing of the diver was. It was a dynamic, splash moment but it was so frozen. That's the kind of drawings I like, like Pete Morisi and coloring book drawings. I'd alter old advertisements or general flat, clip-art like images, and add my own panels drawn in a baseline style, to connect, say, a drawing from an old romance comic of a couple on a bridge to, like, an Adidas ad for a pair of shoes.

I had an idea for an afterlife story separately—"what would a present-day afterlife story be?"—and I also had a general concept of super-doctors, of doctors who save people's lives in unusual ways.

All of these things merged as I was making pages and figuring it out as I went along. I would use anything I had around as a potential Doctors page... Old sketchbook pages, older comics I'd never finished, an ad for a cup of coffee, whatever. I tried to be open to unusual possibilities.

Mostly things fell into place in a literal and unified way.

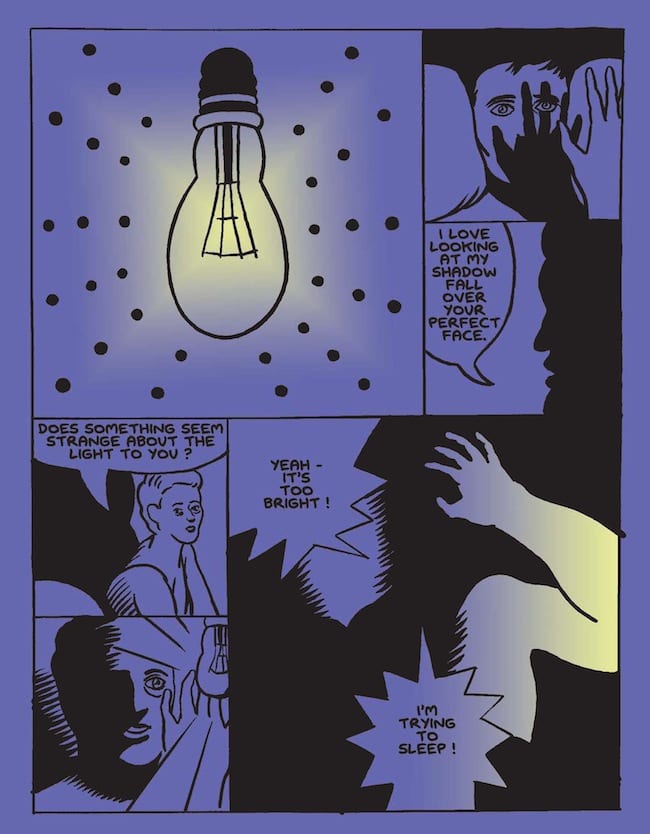

I included some pages that don't literally relate to the story, like the "Ghosts" page or the beam of light page, but they seemed to relate in some nonliteral, abstract way. Whenever I'd try it without those nonliteral pages, something tonally was missing. So I decided to keep them in, as my small contribution to the ongoing war against literal-mindedness! Ha ha ha.

You alluded above to a "baseline style" that worked to unify both the book’s narrative and its references. Can you talk more about what you wanted to give the story (beyond a sense of cohesion) in terms of drawing? There's a line walked in terms of style—lines run over panel borders, making things feel "unedited," which makes for a tension with the stiffer elements that enter in through a number of your sources. But I also feel that certain narrative elements are privileged, if defamiliarized or refracted—like the story's moments of connection, or the kind of dreamy resonance of certain images and shapes (the Brooklyn Bridge, a swimming pool, a tree climbed in childhood). What kind of goals did you have in terms of tone and presentation? The book feels emotionally "close" to the characters' minds.

The word you used earlier -- "affectless" -- is appropriate. I took that affectless/"cold" tone because the content is so charged/"hot." The Doctors story is in melodrama territory. It's all over-the-top emotional stuff. If I tried to draw it in a gooey, sentimental style, it'd be too much. So I was aiming for that matter-of-fact affectless tone, like how doctors behave, but the truth is that I have limited control over how it turns out. It's more of an experiment. The book takes over and turns into whatever it needs to be. I can only look at it afterwards and guess why it happened that way, and make up reasons, provide excuses, etc.

I want to ask a little about Cosplayers in terms of structure. I see each issue of Cosplayers as (among other things) a chance for you to play with the structure of a comics issue in different ways—with "pin-ups," interstitial materials, and different kinds of story structures. So I see a connection to that notion of comics as collage there, but can you talk more about how that idea or premise plays out within those stories? I think of page design most immediately, but I really mean on any level.

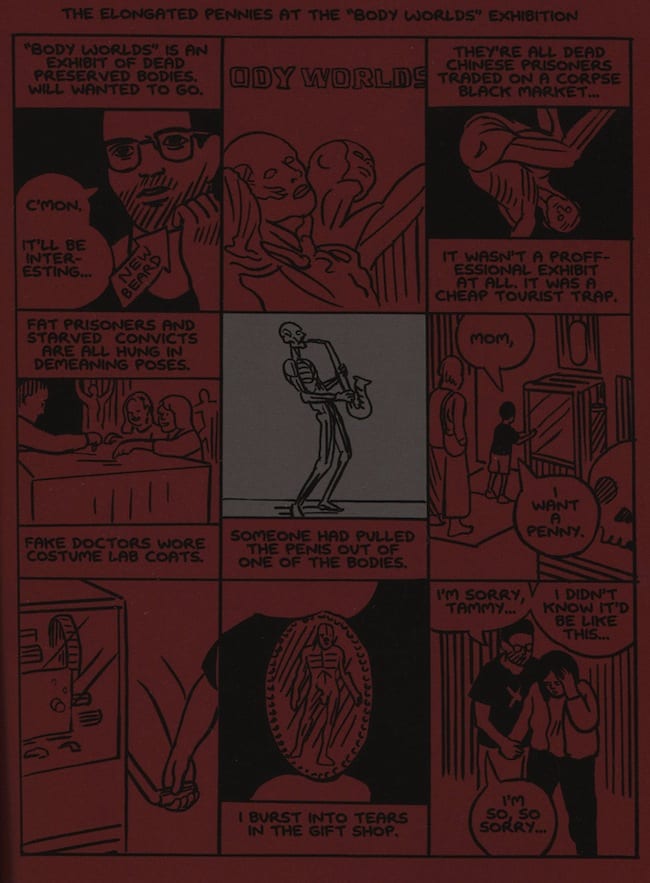

It'll be most explicit in the next issue, which has cut-up comic collages inside of it, but, I can try to come up with an answer, sure. One way to answer is that I drew the first story and kept adding stories, without a plan. I didn't envision a pamphlet at the beginning. First I had one story, then those characters asked for a second story, then I drew pin-ups of cosplayers. I came up with some one-panel gags and collaged them over the pin-ups. The content/subject matter asked to take the form of a pamphlet comic. Then, the idea of doing a second issue that takes place entirely at an anime convention was a no-brainer. It grew organically, piece by piece.

Drawing a cosplayer is interesting because you're drawing Wolverine and you're inking him with a brush and it's computer-colored like how real Wolverine comics are, but we know it's a cosplayer. It doesn't look like Jim Lee's Wolverine. I wanted them to look like real cosplayers. A guy will dress up like Batman but he won't look like Christian Bale's Batman, you know? Maybe he got the bat sign a bit wonky, or he doesn't have Batman's body type. That's part of what I love about cosplay. Fandom is wider and more inclusive and humanistic than most of the stories/characters that the fans are fans of.

Different people like cosplay for different reasons, so these decisions obviously just reflect what I personally like about it.

I'm cosplaying too, in a way, by dressing in this format and inking and coloring in a way that I'm not natural at. I'm like the guy wearing the Batman suit realizing he's not the real thing, but embracing who he is, play-acting, and strutting out there. So it's sort of like I'm collaging myself onto the spinner rack next to the real Batman. It's a merging of the unreal with the real which, also, is part of what cosplay means to me.

Of course there are a lot of cosplayers now who combine different characters to make their own, like the Boba Fett/Snow White creation, but that isn't in my comic.

And conventions are collage-like environments, in that you have Link from Legend of Zelda talking to Rick Grimes from The Walking Dead and all of these pop culture characters are occupying the same physical space. It's like the Werner Herzog quote that I put on the back of the Tezukon issue: "the collective dreams all in one place." It's similar to the Philip José Farmer series Riverworld, where everyone who has ever lived is resurrected alongside the same river and they're all the same age. It's an excuse to have all of these people he's interested in interacting with each other, like the girl who inspired Alice in Wonderland talking to Jack London. Gary Panter's Dal Tokyo is another story where characters/things that the author is interested in are all put together in the same sandbox. I reference those creators not to compare myself to them, but to illustrate a way of looking at comic conventions. A person's mind is filled with these things... It's natural to throw a party and invite them all to meet each other.

I'm interested in how you allude to your own position in the stories, which seems fairly conscious. There are the references to what you know—the Tezukon show program in issue two, as well as those pin-up drawings—which foreground the interplay between our tastes as consumers and the art we make. But it's most explicit with the Paulie Panther cameo at the end of issue two, in which he serves as an equalizing force—implying a level of arbitrage in how all these different fictional characters exist, meet, and interact with one another at these things. Within the story, he's as real as Tezuka or Herzog, or any of these other characters. Does spending time within these fictional worlds concern you? I don't want to make you explain your comic, exactly, but issue 2 seems to meditate on those kinds of questions.

Your question is "how much of myself is in this?" Is that right? Because Panther is one of my characters. I think that's what you're asking, and I will try to answer it. Well, it's all me, I think. It's my fantasy, in a way. I think inserting Panther was about that. When I was a kid I used to make programming schedules for fictional anime conventions. I've been going to anime and comic conventions since I was 12, and I'm 31 now. I've had a wide range of experiences at them, of course. Lots of awesome, positive experiences, and horrible ones, and everything in-between. I can swing wildly at a convention from thinking "I love all this stuff" to "it's all garbage" to, most often, a wide range of (often contradictory) feelings in the middle of those extremes. I wanted Cosplayers to represent these feelings, and to take a positive, but informed, tone. Those Cosplayers issues were very easy to write, because I knew those people, those situations -- I had it all in the back of my mind ready to go.

Hm. That answers part of the question, but let’s see if I can try and clarify the rest. There's an extent to which the story seems critical of Tezukon and its attendees, and it draws out some parallels between cosplaying/attending shows and then the acts of cartooning and reading comics. There's the suggestion of a narrow subculture engaged in a kind of pariah activity; the book’s populated with bitter obsessives who aren't so good with people. But then the introduction of Paulie draws a comparison between cosplaying and your own cartooning, making the reader freshly aware of “your mind,” as you mentioned, being the force behind the work. So would you apply a kind of transitive property here? Do you see something innately problematic about making comics that relates to cosplaying, where you also spend a lot of time immersed in these fictional worlds?

Okay, I understand your previous question. You meant "concerns" as in "worrying." Huh. Well, no, I'm not worried about comics, cartooning, cosplaying, fictional world immersion. I get your question: I burrow myself into these fictional worlds just like these characters do. I think it's fine. I like it, actually. Does it make you not so great socially? Sure. But maybe people shouldn't be as good socially as they are! Can it damage your life? Sure. But it can also enrich your life. I think art and stories have a lot of value. Part of their value is as empathy-building machines, or empathy exercises. So maybe I stressed the solipsistic aspects too much earlier. Don't forget: Tezuka was training to be a doctor, but he quit when he realized drawing comics would help more people! Ha ha. Case closed!

But seriously, it is a good question. Early in Cosplayers 2 a fanboy is talking to another fanboy about whether or not people sleep with strangers in hotels, and the second fanboy says that a character does in an OVA. It's a gag because, like you said, this guy doesn't know anything from the real world. He just knows about life from anime and, obviously, anime and comics have generally displayed an understanding of relationships equivalent to porn. So I can see why that would be a critique of this guy, and fanboy culture, but I honestly didn't think of it as a critique when I wrote it. I just thought that that's what that person is like, and he's one person in this tapestry of characters at Tezukon. I wasn't interested in critiquing an obsession with fictional world's effect on people. I was more focused on having an empathetic but realistic eye on these characters.

The only "bitter obsessive" I can think of is the manga scholar character, but I like him a lot! He's more cartoony than the other characters, but I did that to set up the ending, which I hope is a very empathetic moment.

Yeah, you've got it—I'm sorry that wasn’t more clear. I do agree that empathy comes to the fore here (and I think that's true of most of your stories). It's kind of like what the guy says in issue 1 about video games, expressing this idea that these things can foster genuine and lasting connections—and in a real sense actually matter.

So I definitely think you're dealing with fully realized characters in these stories, but you also toy a lot in both Doctors and Cosplayers with a sense of graphic flatness. I remember, for instance, after New School came out, reading about your employing a "dumb" [or inexpressive] line. That's not quite what you're doing here, but I can see you working off similar ideas, toying with gradients or rendering figures with all one solid color or as silhouettes. Is there a reason a "flat" sensibility continues to interest you? There's a relationship to that idea, definitely, of "comics as collage," which seems to open up (especially with that first issue) a lot of possibilities in terms of page design.

Sometimes artists who are inconsistent look at consistent artists and think, "Why does it all look the same? They do the same thing over and over?" when in fact there's often a wide range in their work and they don't have a choice -- it comes out looking similar. Similarly, consistent artists look at inconsistent ones and think, "Why does it look so different? Are they fucking around?" when in fact there's a lot of repeating ideas and they don't have a choice -- it comes out looking different.

I tried to do another book like New School right after it. I wanted to keep that mode going. For once in my life, I felt really happy with my drawings, especially the latter half of that book. So I went along, but the project just fizzled. I think I needed to chill out and recuperate somehow. Constructing the collages and piecing Doctors together was my way of doing that, and that bled into Cosplayers. I'm not super happy with the Doctors or Cosplayers drawings. I see it more as transitional work to get between New School and what I'm doing now, at the library, which is called Discipline.

When that comes out I'm curious if you'll think it has that flatness you're talking about. I know what you mean. I like flatness. Comics are flat. But if you're surrounded by beautiful books from the 1800s that are filled with rounded, subtle illustrations, you get your ass handed to you, craft-wise. It's shaken me up this year. I'm reaching for a subtlety in the drawing that I wasn't attempting before.

I think I understand what you mean about those older drawings—I’ll be curious to see that stuff. I don't know how much you want to talk about the new book, but I'm curious whether there are specific parameters you had set for it going in, or what kind of rules you've outlined for yourself. Can you talk more about that experience of doing research-driven work? And is your character [a Quaker soldier in the American Civil War, right?] an actual historical figure?

Yes, it's about a Quaker soldier in the American Civil War. Quakers were pacifists, but also antislavery, so the War presented a conundrum. Many Quakers fought. Quakers, at that time, didn't listen to music, and they still said "thee" and "thou" (the informal way of speaking, although it sounds formal to us now) and so a young Friend joining the Union would have a culture-shock experience on top of a totally crazy, brutal war. My story is historical fiction, but it's mostly clipped from actual soldier diaries and letters and other things that I'm finding here at the library.

I was raised Quaker and in Richmond, Virginia, so I was vaguely familiar with a lot of these things. I had it floating in the back of my mind and I wanted to attempt a project like this a while ago, but the amount of research was intimidating. My book is dreamy. It's another weird book. It's not meant to be instructional, but I wanted it to be informed. I didn't want to b.s. my way through it.

I actually researched things for ClockWorld, and a lot of people helped me on that who I stupidly and absentmindedly didn't keep track of and thank in the back of the New School book. I'm keeping track of absolutely everything now, so every sentence of Discipline will be sourced, and a lot of people in the different divisions of the library, and elsewhere, have helped me a lot. This year has been a wild ride for me.

The history is incredibly interesting, even though most of it won't end up in the book. So many things about Quakerism are radical... Pacifism is radical. Their method of persuading slave-holders to free their slaves wasn't by preaching the evils of slavery, but by asking the slave-holders to ask themselves if slavery "feels right." Obviously one has to wonder how effective that was. Absolute consensus decision-making is radical. The fact that there's no minister, or that everyone's a minister, makes sense to me. Anyway, it's interesting to think about these things while making a book.

I have an outline, but it's flexible enough so that I can research and make changes and rearrangements while still producing drawings. It's not like I'm giving myself a long illustration assignment. It's malleable. When you see the eventual book you'll see what I mean.

Based on what you're saying and even just on the title Discipline, it sounds like you're trying to learn, basically, a whole new way of drawing—alongside (or wrapped up in) your investigations of all these philosophical questions. Do you have particular signposts or goals in that, aside from drawing on the subtlety and facility you mentioned finding in these sources? Or is it more exploratory? I'm specifically wondering how the structure of the book affects the drawings.

It's exploratory. The goal is to draw like myself, but also in a way that vaguely feels appropriate to the time. It's not a pastiche. It's not a whole new way of drawing for me. The first drafts of the drawings look like New School pages, more or less, drawn with thick lines and fields of black, only now when I make more finished versions, the black becomes hatching, and there are subtler notes being played I guess (and hope). Maybe there's no point in talking about it until the book is done. But, really, I'm just going along, getting interested in things, moving along through life.

You could look at a Gustave Doré print and be like "what's all this stuff going on?!?" but then you realize that there's a giant shaft of light in the center of the image, and that in fact it's basically graphic, Roy Crane territory, only instead of a solid black there's a field of hatching and another graphic composition inside of that. And so you don't have to press the restart button to understand it. Of course some artists have idiosyncratic, unusual decisions all over the place, like Thomas Nast, but then you see how Robert Crumb picks up Nast and turns it into a less idiosyncratic system of hatching. Crumb made Nast consistent, which cartoonified him, in a way. Comic drawing is about consistency. So, modern artists help you understand older ones, obviously... That's the history of art!

But maybe you are also asking about the spiritual aspect of it... how researching a religion affects drawing. But that's too much for me to answer right now... I'll try to answer that when the book comes out. A short answer could be: "Drawing is a truly transcendental thing."

I think of Doctors as inhabiting a "dreamy" space, too—and as being similarly structured (at least in terms of process). I noticed reading that there weren't any drawn gutters between its panels, signaling a focus on the spaces, or rifts, between its pages, which were composed in relative isolation. How conscious were you, as you worked, on those ellipses between pages? In reading I felt you'd deliberately given a kind of structure to those negative spaces, shaping reflections and expectations.

Yes, exactly. The panels are closer together because it emphasizes the page as a unit. The colors do that too, more overtly. When you flip through the book, I hope you immediately sense that each page is a separate scene/thought.

Also, you are absolutely right about the ellipses between the pages. That was the most gratifying part of making the book. Those negative spaces are the meat of the story! Ha ha ha. Since I could remove/rearrange pages in such a flexible manner, I'm simultaneously filling those spaces with meaning while making concrete diptychs with the facing pages.

Reading is a tunnel-vision experience. If I insert a page, it instantly alters the meaning of everything after it. What if I remove a scene I thought I needed? Now I go from point A to point C. Maybe I didn't need point B at all. Well, what if I put in point X between A and C? Holy shit. Suddenly something happens that was unexpected. Maybe I keep it in, or maybe I take it out, but I got to try it in an immediate way.

That was the process of making the book... how can the spaces between the pages be as meaningful as the pages? It's sort of an existential question. It's appropriate to the story, and it is the story.

Doctors investigates a lot of other spiritual and existential questions, but it seems to do so by making its character work oriented towards them, grounding those issues in a way that feels organic. You mentioned a "spiritual aspect" to drawing for Discipline, but can you talk about the same thing with regard to Doctors, and approaching those questions from the minds of all these different characters? I'm especially interested because it's rare to find work that deals successfully with such a range of (usually) abstract topics: memory, death, religion, life after death... I think because it treats them as these kinds of gaps to ponder.

I'd say Doctors has more of an "existential aspect" because of the connections between scenes. The doctors enter people's afterlives to bring them back from the dead, but they only save rich people to settle their estates, and the people always die again shortly afterwards, so they have this amazing discovery and technology, but what's the point? The characters are haunted by a feeling of meaninglessness. I don't know how to answer how I approached it from the minds of the characters... I used my imagination.

As to the spiritual aspect of this being an afterlife story, I don't know what to say besides the obvious... Afterlife myths historically come from religions/cultures. I just wrote one that made sense to me personally, in my present time and place.