I recently finished Stanley Cavell’s 1971 book of film philosophy, “The World Viewed” (with a long addendum from 1979.)

The book is a mixed bag. Many of Cavell’s readings are thoughtful and sharp. On the other hand his take on one film I know well, “Rosemary’s Baby,” is so misguided as to be actually offensive. (He claims that the film is about Rosemary’s husband’s impotence rather than about Rosemary’s rape, and then muses on the exact nature of Rosemary’s sin, which he determines has something to do with the fact that “Rosemary does not allow her husband to penetrate her dreams, allow him to be her devil, and give him his due.” Which I suppose is a roundabout way of saying that her sin is that she was insufficiently accommodating and so her husband had to rape her, or let the devil do it for him. Cavell also seems to believe that the movie is about motherhood, when it’s rather clearly about pregnancy. His inability to tell the difference is of a piece with a consistent incapacity to imagine that somewhere, somehow, the audience for some movie or other might include women. In any case, when you are more misogynist than Roman Polanski, you are in serious trouble. )

Where was I?

Oh right.

So some downsides. But on the other hand there’s lots of interesting theoretical material. Cavell’s book is fascinated with the relationship between film and reality. For him, the most salient fact about film is the manner in which it technologically, automatically, produces a reproduction or an image of the world that is neither a reproduction nor an image. Film is the world itself, though a world from which we (the audience) are exiled; we can watch but not interfere. Cavell therefore sees film as directly confronting Western philosophical skepticism — the Cartesian fear that we’re trapped in our minds with no way to perceive or access reality — or, indeed, the fear that our minds are all there is, and there is no reality to access. The loss of objective reality is also the death of God, and in embodying that absence, film replaces religion.

A world complete without me which is present to me is the world of my immortality. This is an importance of film — and a danger. It takes my life as my haunting of the world, either because I left it unloved (the Flying Dutchman) or because I left unfinished business (Hamlet). So there is reason for me to want the camera to deny the coherence of the world, it’s coherence as past: to deny that the world is complete without me. But there is equal reason to want it affirmed that the world is coherent without me. That is essential to what I want of immortality: nature’s survival of me. It will mean that the present judgment upon me is not yet the last.

So for Cavell, the fact that what film shows is reality itself, not a representation of reality, is vital. He emphasizes this, for example, in his comparison of photography (which is linked for him to film) and painting.

Let us notice the specific sense in which photographs are of the world, of reality as a whole. You can always ask, pointing to an object in a photograph — a building say — what lies behind it, totally obscured by it. This only accidentally makes sense when asked of an object in a painting. You can always ask, of an area photographed, what lies adjacent to that area, beyond the frame. This generally makes no sense asked of a painting. You can ask these questions of objects in photographs because they have answers in reality. The world of a painting is not continuous with the world of its frame; at its frame, a world finds its limits. A painting is a world; a photograph is of the world. What happens in a photograph is that it comes to an end. A photograph is cropped, not necessarily by a paper cutter or by masking but by the camera itself. The camera crops it by predetermining the amount of view it will accept; cutting, masking, enlarging, predetermine the amount after the fact…. The camera, being finite, crops a portion from an indefinitely larger field; continuous portions of that field could be included in the photograph in fact taken; in principle it could all be taken. Hence objects in photographs that run past the edge do not feel cut; they are aimed at, shot, stopped live. When a photograph is cropped, the rest of the world is cut out. The implied presence of the rest of the world, and its explicit rejection, are as essential in the experience of a photograph as what it explicitly presents. A camera is an opening in a box: that is the best emblem of the fact that a camera holding on an object is holding the rest of the world away. The camera has been praised for extending the senses; it may, as the world goes, deserve more praise for confining them, leaving room for thought.

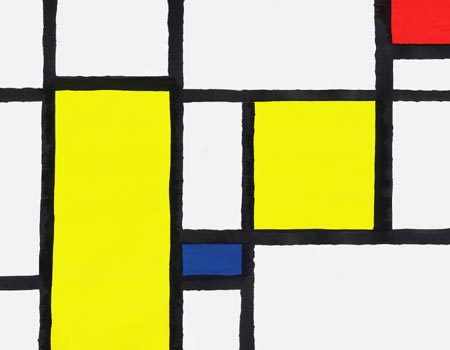

Cavell later, interestingly, suggests that abstract paintings are, in their cropping, more like photographs than like traditional paintings. His reasoning is that in abstract paintings the cropping, as in photographs, is arbitrary. The image is confined rather than finished, which is an acknowledgement of a broader reality.

As it happens, this is exactly my experience of Mondrian’s pantings. The blank grids arbitrarily cut off at the edges — whenever I look at his work I get this very creepy sensation that the image is not a frame but a window onto a infinite flat landscape of colors and lines and squares. The fact that the pattern is individualized — that you can see the mark of Mondrian’s hand, the wavering of the lines — makes it somehow more chilling. This isn’t just a computer-spawned iterating piece of graph paper; someone has created this and gone on creating it, past the edges of the canvas and on and on forever. It has the solidity of its imperfection and the conviction of its arbitrary limitation. The world is a endless field of markings created by an intelligence I don’t understand for a purpose that eludes me. As Cavell suggests of film, when I look at a Mondrian I am a ghost looking into a box.

The thing is though…I get this sense of a world without me far more strongly from looking at Mondrian than I do from looking at photographs or films. Indeed, some photographs can give you almost the opposite sensation:

That’s “Milk” by Jeff Wall from 1984 — and like Wall’s photos in general it’s rigorously, even ostentatiously, composed. The edge of the image cuts the wall off with such perpendicular precision that it seems impossible that it could extend beyond the frame; the bricks are so flawlessly horizontal, the wall so perfectly flat, that they seem unreal — a stage set. Even the erupting, splashing milk seems like a trick, a too neat mess against the too rigid pose of the seated man. The image doesn’t seem of the world. It seems like a world in itself, one with its own absolute boundaries and it own frozen logic. The brick, the milk, the man, the bit of the rest of the house that’s visible; this isn’t a segment of existence. This is the whole enchilada. The artist could almost have set out to deliberately parody Cavell. You want reality? Here. Talk to the wall.

Tarkovsky (who I discussed recently here) is less ironic and more elgaic, but “Solaris” also uses the screen’s boundary as a boundary. In this film, what’s outside the screen is not infinity, but nothing. If what you see in a given frame of “Solaris” is arbitrary, that’s not because the screen shows a segment of reality, but because it shows a segment of a mind. Cavell argues strongly that films are not dreams…but Tarkovsky in the sequence below argues even more forcefully that they can be.

This final segment of the film, where the camera pulls back and back, revealing that the idyllic country home is a projection, a construct in the middle of an ocean in the middle of fog in the middle of white seems to insist that film is not “the world itself”, except insofar as the world itself is inside us. If we are exiled from the world of “Solaris”, it’s because it’s an individual vision, not because it’s reality. And if Tarkovsky suggests that in part reality is individual vision, that our dreams contain us, then that insight seems directly opposed to Cavell’s notion of film’s ontology. Cavell says you can always ask what lies beyond the borders of a photograph (or a film); Tarkovsky responds that what’s beyond is a mist, a blank — the dream of nothing that’s the edge of your dream. Film for Tarkovsky isn’t a way to become insubstantial and so pass through the bars of the Western philosophical prison. Rather film (or at least “Solaris”) is a lyrical assertion that the same ghostly prison is waiting for us across time and across space. Wherever you go, there you aren’t.

Unless you’re Hiroshige and you go to Edo.

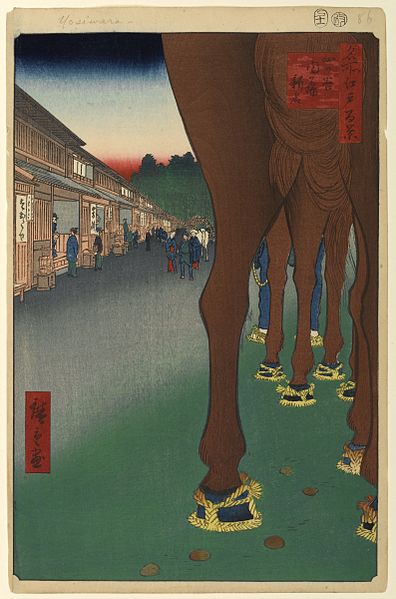

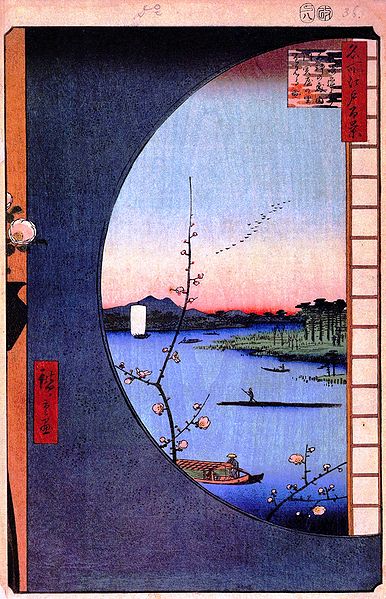

The image above is from Hiroshige’s 100 Views of Edo. To me, this print seems to do precisely what Cavell says traditional paintings (or presumably drawings) don’t. That is, even more definitively than the Mondrian, it insists that existence does not stop at its borders. That ass up there is attached to a horse. Indeed, the perspective here demands not only that you go broad, but that you go deep. The place from whence came the poop is as real as the horse head, though you can’t see either. The border here cuts a segment of the world both from what’s around it and what’s inside it. Hiroshige’s ontology crawls up into everywhere.

Cavell seems at some points to argue that hidden depths such as this aren’t really possible in painting; that they’re the exclusive purview of film.

In paintings and in the theater, clothes reveal a person’s character and his station, also his body and its attitudes. The clothes are the body, as the expression is the face. In movies, clothes conceal; hence they conceal something separate from them; the something is therefore empirically there to be unconcelaed. A woman in a movie is dressed (as she is, when she is, in reality), hence potentially undressed…. A nude is a fine enough thing in itslef, and no reason is required to explain nakedness…. But to be undressed is something else, and it does require a reason; in seeing a film of a desirable woman we are looking for a reason. When to this we join our ontological status — invisibility — it is inevitable that we should expect to find a reason, to be around when a reason and an occasion present themselves, no matter how consistently our expectancy is frustrated.

For Cavell, then, the prurient expectation/anticipation of a woman’s nudity is based upon the ontological reality of film and the invisibility of the viewer. These conditions are not present in painting nor in theater.

It’s a provocative insight (as it were) — the only difficulty being that it seems to fairly clearly be nonsense. I like the way that Cavell mentions theater quickly in that first sentence and then skips lightly past it, presumably so that he doesn’t have to deal with the fact that, if you follow his logic, he appears to be arguing that theater actors are physically incapable of taking off their clothes.

For that matter, even painting isn’t above the occasional tease.

That’s called “The Fur,” which I find it difficult to believe is not a double entendre. The reality of that painting is exactly what you’re thinking the reality of that painting is. If Cavell doesn’t want to look under there, that may have something to do with his subjective sense of modesty or his subjective preference, but it’s got fuck all to do with objective ontology.

Still, Cavell does have an interesting point, though not exactly the one he intends. Specifically, Cavell in the passage above is, it seems to me, blurring the line between ontology and narrative. The fact that there is nudity beneath the clothes and the fact that those of us with a prurient interest in the female body “expect” to see that nudity — that’s a desire for narrative payoff, or climax. Cavell in his book deals entirely with narrative film; perhaps for that reason, he fails to take into account the extent to which reality is not established solely by mechanical means (the film process), but also by the engine of sequence. The reality of (narrative) film from which we are excluded is a narrative reality; it is not just narrative because it is real, but real because it is narrative.

And that narrative, it seems to me, does not exist solely in film. The Rubens painting above — is the extrapolation in which the drapery falls less present because the model will never actually move? Or does her eternal, level gaze make her more real? A painting crops a moment from that moment’s past and present just as a photograph crops a space from the photograph’s surroundings. The narrative of the woman in the picture is not less real because we do not know what happened in the next instant. On the contrary, her reality and her story is validated by what is left out. We know she has a story precisely because we see only the moment Reubens captured, just as for Cavell we know film is a world because we see only the bit of it that the camera shows. By Cavell’s logic, painting — in cutting out more — is actually better at being film than film is.

Which brings us back to Hiroshige.

In showing us disparate scenes, and disparate moments, of Edo, Hiroshige surely makes it more actual, more solid, than it could be if the city served merely as the background for a story — or even perhaps than it would be if it were filmed. That ontological solidity comes about in large part precisely because Hiroshige’s Edo is not solid; it is not one thing. Instead, it is glimpses, perspectives — the sum total of an infinite number of individual views.

Nor are these views necessarily our views.

Who is seeing this? Even a modern day film would be hard-pressed to get that shot without special effects. What Hiroshige presents here is a God’s-eye view — but the fact that this is an impossible vision does not make it unreal. On the contrary, it suggests more definitively that Edo is real — that the infinite subjective views are not tied to human subjectivity. Hiroshige’s Edo is, in fact, more real than any view of Edo we could see by ourselves; the parts are not necessarily greater than the whole, but they suggest the whole more fully than any parts we can see. I am exiled from the real Edo…and it’s my exile that tells me that Edo is real. That’s why, perhaps, even God does not see the entire bird.

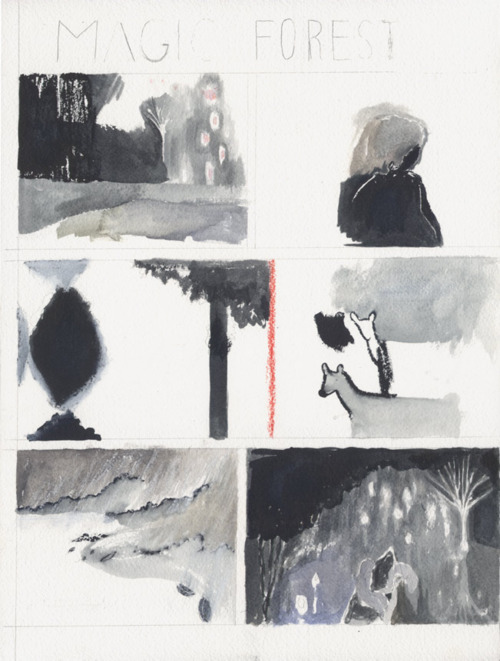

I think something similar is happening with Blaise Larmee’s “Magic Forest.”

I have to admit, I don’t love this piece. It seems to replicate the current contemporary art zeitgeist’s default feyness without much visual oomph of its own. The images remind me uncomfortably of those cute John Lennon characters that adorn children’s bibs or placemats, but blurred out so as to seem more profound.

But while I’m not so into the execution here, the concept is intriguing. Derik Badman gets at this in a recent post in which he discusses the ways in which Larmee works with and against abstraction:

The wonderful atmosphere of Larmee’s page is partially generated through this non-narrative descriptive place. The appellation of “magic” to the “forest” modulates my reading of the imagery. The images are in some way otherworldly. Their abstract qualities, for instance the ovoid shapes that appear in panels one, three, and six, are integrated into this conception of a place that is elsewhere, potentially unreal. Where the marks stray from clear representation, this unreality is introduced. In panel four a dark shape hovers next to the head of the rear deer(?), like some kind of specter. It could be just a compositional shape, but once I start reading, it takes on this other life.

As Derik says, the place shown here is “elsewhere, potentially unreal.” But I’d argue that it is also potentially real; the title “Magic Forest” could be seen as (gently) ironic. Each panel shows us a glimpse of a world, a cropped instant from…not Edo, obviously, but somewhere. These are scenes from a reality, and who’s to say it isn’t ours? In his discussion of modernist painting, Cavell quotes Wittgenstein, “Not how the world is, but that it is, is the Mystical.” Cavell then goes on to say, “however we may choose to parcel or not to parcel nature among ourselves, nature is held — we are held by it — only in common….It reasserts that, in whatever locale I find myslef, I am to locate myself.”

Whatever locale Blaise shows is shown only in glimpses. There’s nowhere you can stand to see all of reality; what you see of it is partial. The existence of objectivity is guaranteed by the fact that you only see it subjectively. Cavell — in his focus on the unified view of narrative film — sometimes forgets this. That’s why, I think, he can claim a special ontological status for movies and, almost by accident, for male viewers. Larmee knows better. There’s no one place from which to look at the forest. That’s how you know it’s there.

“His inability to tell the difference is of a piece with a consistent incapacity to imagine that somewhere, somehow, the audience for some movie or other might include women. In any case, when you are more misogynist than Roman Polanski, you are in serious trouble.”

Are you not aware that this Bud-drinking, trailer-dweller of a scholar specializes in women’s pictures? Maybe he’s a latent homosexual who hates all women.

Women’s pictures are certainly not what he focuses on in this book.

What exactly do you mean by women’s pictures? He talks about female stars a good bit…but pretty much always in terms of their relationship with male viewers, as far as I could tell. There’s one passage where he talks about how female stars are more important than male stars to an enjoyment of cinema, and there’s not really ever an indication that he’s considered that that might have something to do with his own subjective stance, rather than with some sort of absolute law of cinema.

As I say, it seems of a piece with his ontological approach, and with his insistence that narrative Hollywood film defines film. There’s little sense in the book that he’s thinking very much at all about the way different audiences might view different films in different ways. And more or less by default, the viewer ends up being a heterosexual guy like him.

Since the misogyny seems to be embedded in the approach, I could see him taking a different theoretical approach elsewhere and coming up with a less misogynist result. The misogyny really does seem almost an accident, which doesn’t make it any less irritating, but does suggest that he might be able to do better under different circumstances.

Also…it seems really bizarre to me that you would suggest that misogyny has anything to do with being lower class. There’s a long tradition of misogyny in the academy…and certainly in philosophy. Cavell’s philosophical predilection to assume a male subject is very much in that tradition.

Actually, lower-class misogyny very rarely takes the form of forgetting that women exist. That’s the sort of thing the intelligentia do.

“What exactly do you mean by women’s pictures?”

Weepies, melodramas.

Here Thomas Elsaesser discusses Cavell’s approach in relation to post-structuralism, feminism and psychoanalysis.

If you want to caricature him as a misogynist, well, okay.

“Also…it seems really bizarre to me that you would suggest that misogyny has anything to do with being lower class.”

I was just goofing stereotypically on your ad hominem. I agree rich men can hate women, too.

I haven’t caricatured him as anything. I explained why I thought this particular book was misogynist. You can disagree if you’d like. Ideally that would involve engaging with the points I’ve raised in some vague manner.

Or, you know, alternately, you could babble about trailer parks and insist that he can’t possibly have said unfeminist things here because he wrote about melodramas somewhere else.

Thanks for the link; I’ll check it out….

“I was just goofing stereotypically on your ad hominem.”

But your goofing suggests strongly you didn’t understand the ad hominem at all. Which makes sense, since it wasn’t an ad hominem in the first place.

We’ll just agree to disagree on whether suggesting Cavell is “more misogynist than” a guy who drugged and raped a teenage girl is both an ad hominem and caricature.

and misogyny isn’t the same thing as unfeminism.

Nope, misogyny and unfeminism are different.

Rosemary’s Baby isn’t actually misogynist though. Or at least, it’s complicatedly misogynist, which was sort of the point.

Arguing (as Cavell does) that Rosemary in that movie deserves to be raped does in fact make him more misogynist than Polanski, who takes care to place our sympathies with her throughout the film — and who does not confuse pregnancy and motherhood as Cavell does. In this case, Cavell is more misogynist than Polanski — which, as I said, is an unfortunate place to wind up. (Though I have no reason to believe that Cavell is anything like as unpleasant as Polanski in his personal life.)

This is an interesting piece, Noah. And I like the counterexamples you came up with, especially the Mondrian.

Part of me wonders what Cavell would make a video games. Visually, they share many qualities with film (or animation, as it were) but the player is not a passive observer of the world – they have to interact with it. Obviously it varies, some games stress narrative more than others.

Really good piece. But!

When images start portraying descriptive frames, framing with framelessness, their meek protests of indeterminacy and incompleteness are often offset by a mighty weight of random ephemeral detail being wielded for pointless irrefutability.

Richard, video games are interesting. For Cavell the not being able to affect the world is really important, it seems like….the fact that there’s no set beginning or end might be something he’d be interested in…I just don’t know for sure. Is there any effort to approach video games through aesthetic theory at all?

Bert, I’m not sure I’m following you. Are you saying that something like Solaris undermines its own indeterminacy because there’s so much additional detail that goes to make up the world of the film? Cavell might like that…arguing that even when the film is about being a dream it still insists on its reality. I’m not sure I entirely buy it though….

And is that only for film? Or is it for something like painting too? (Too much detail working against claims of artificiality….)

Some colleges are adding a new discipline called Game Studies, so I’m sure there are plenty of academic papers floating around. I haven’t seen any books apply aesthetic theory to games though. Compared to film, there’s a notable lack of significant scholarly writing on games.

Though that’s likely to change in the next few years.

I was thinking more of Hiroshige or documentaries or Abstract Expressionism, but psychedelic realism could be similar- “this isn’t a fairy tale… it’s an actual subjective impression, recorded with high-tech synaptic sensor technology.”

Yep, still not following you exactly. Hiroshige or documentaries don’t frame with framelessness, do they? I mean, the point for both is that there is a frame which shuts out the rest of the world, and therefore points to it. The claim of incompleteness doesn’t seem meek at all; it’s a declaration that what they have is only a part, and therefore an assertive reification of the rest. The mighty weight of random detail is an indication of how much of the world there is, even in this partial bit — and the irrefutability doesn’t seem so much pointless as the point.

I must just be dense…maybe you could explain what you’re getting at in terms of a particular piece? (If you get a chance at some point…)

Here’s a simple (if simplistic) explanation of my issue– the cropped abstracted image or the unmediated interview is always relativistic, and (naturally) at the same time egotistical. It’s beautiful to crop and interview, narcissistically so, as it asserts the world as a mirror. I’m not trying to make some weird Platonic formalis,=morality equivalency for individual pieces, but as a phenomenon, I think you can evaluate ethical motifs that are more subtle than, say, sexism and racism.

Sorry about my typos. It all gets back to my hangups about photography as an art form– the appropriation of scopic gnosis by an auteur just makes me queasy. That’s my thing.

That’s maybe slightly clearer….though I’m not sure why that would implicate Hiroshige if it’s about photography?

Unless… it sounds like the idea of seeing the image as real, as having ontological power, is itself problematic? So you’re skeptical of Cavell’s whole effort to make art replace or equal reality — or else you think that he’s right that this is what film and photography claim, but you feel it’s ethically dubious, inasmuch as it elides the extent to which cropping does not point to the world but to itself; the boundary is the boundary of the subject imposed on the world. It’s modernist humanism; the individual becomes the measure of the world rather than vice versa. Maybe?

I think that makes sense for what Mondrian is doing. I like the creepiness of it in him; he feels like Lovecraft to me (who was also a creepy humanist. Not to mention a racist.) I think it makes sense for a lot of the narrative film that Cavell’s into as well; like Hitchcock, for example.

Jeff Wall and Tarkovsky are so much about artificiality that it’s hard to see either of them as doing exactly what you’re saying. I think Hiroshige is really undermining the idea of an individual or single human perspective as binding or predominant. I’m pretty sure there’s a non-humanist ideology there — though Buddhist rather than Christian, obviously.

Cavell’s assertion reminds me of Donald Judd with his multiple cubic explorations of the gestalt.

I think you got my gist. I unreservedly like Jeff Wall and Tarkovsky, to be clear– but to say that you can distinguish them from the Hitchcock psychologistic thread is dubious.

So and/but yeah… I don’t relish crapping on Buddhists or anything, the way Zizek and other aesthete atheists do. And I could elaborate on my respect for that tradition. But solipsism is solipsism, whether the reality being appropriated is internal or external. Awareness isn’t there to impel action, but rather is traded in for any possibility of action.

I don’t know as much about where Jeff Wall is coming from. I see him as a satirist, I think, which isn’t unsolipsistic, but seems like it is somewhat different form Hitchcock’s solipsism.

I think Tarkovsky is fairly committed to some kind of at least quasi-Chrisitian vision. Solaris is absolutely solipsism…but it’s a solipsism that seems like it opens outwards, or at least has the potential to open outwards. I guess it’s the question of whether Kant is solipsistic — reasonable people could disagree maybe.

As I sort of implied in passing, I think Cavell’s effort to create an ontology of film is vulnerable to critique from the perspective of someone who’s actually willing to come out and say what they think reality is. He’s not quite forthright about the ways or whys of film replacing religion — it seems like he’d be hard put to defend himself (except on grounds of basic disbelief) from someone who said, you know, film is not God because God is God.

Jason, I’m not familiar with Donald Judd. I’ll check out that link….

Going back in comments a bit; I skimmed the essay Charles pointed to about Cavell and feminism. I would say that the description of Cavell’s position seems quite different from where he’s coming from in The World Viewed. If I understand the description aright, the author is saying that Cavell sees the melodramas as attempting to interrogate the question of women; to discover what women is. That seems to link up with someone like Linda Williams, who sees porn as a kind of rage for the real — more about a desire to (sadistically) know women than about eroticism per se. I didn’t get that from anything Cavell said in World Viewed — the latter focuses (in the Rosemary’s Baby passage) on what women need to provide for men/children, and in their failures as sins (ultimately deserving rape, I think). Also, there’s a fair amount about how individual female actors are exciting/interesting — which is presented in terms of female autonomy, but seems to have more to do with male pleasure, and seems in general fairly problematic to me.

Interestingly…I could be misreading, but that essay doesn’t actually seem to consider female viewers especially. As I noted in the essay, Cavell generally posits a unitary viewer, who often seems to be male by default. His reading of the melodramas, at least form what I can tell, seems to focus on how those melodramas relate to male interests/questions/desires — so even in a genre that is fairly clearly directed at women, he doesn’t seem to be interested in/able to talk about women as viewer. (Though I could be misinterpreting that, since I was reading quickly an essay about his work, rather than slowly reading the work itself. Perhaps Charles can correct me if he feels I’m very off base.)

Anyway, it would make sense that Cavell might move away from (more or less accidental) misogyny to a more conscious feminism. There was a lot of feminist film theory done through the 70s. Cavell’s smart; he probably read some of it and thought about it.

Not that I’m actually upset, but I feel just the teeniest bit patronized when my arguments are reduced to a faith-based ontology. I ended up committing to faith because, basically, I feel like a God should exist, not because there’s proof– since who needs faith if there’s proof?– but because there needs to be a name for that which dwarfs us in the scheme of existence.

The relationship between film and desire is a fine example of why I don’t want to just put my trust in aesthetics and be done with it. The self-awareness of the frame is connected (a la Genesis) with the self-awareness of our own (as Cavell puts it) “nudity.” The possibility of perversion is the possibility of knowledge is the possibility of slavery.

Donald Judd arranges various sorts of identical bricks in symmetrical lines. Definitely better as a possibility than a realization.

Sorry; wasn’t intending to be patronizing. But it seemed relevant to bring faith up — especially since absent that context I was having a lot of trouble figuring out what you were saying (which isn’t your fault, obviously.)

No offense taken. But the humanism and relativism charge seems to stick whether or not I endorse a transcendent big Other. And yet and regardless, I think you understood what I was saying just fine.

I really didn’t! I get it now, but I was at sea at first….

But yes, the humanism and relativism charges do still stick…but I still think they end up being more forceful if you have an actual position you’re coming from. Otherwise, it’s hard to explain why you’re not another. (Which I think is definitely an issue when I poke at relativism and humanism. Relativists sneering at relativism — I’m not sure how convincing that is overall.)

Well, if the 1990s taught us anything, I guess, it’s that there’s some rhetorical force in one’s identity– even if it is provisional and constructed.

But, like I said, I would have said those things (as far as I know) before I identified as Christian. Matching up values and beliefs is something everyone should wrestle with, but it doesn’t mean that arguments are off-limits based on identity. Consistency is the something of something, after all.

The work derives its value from the absolute wholeness of the assertion of form.

“Donald Judd arranges various sorts of identical bricks in symmetrical lines. Definitely better as a possibility than a realization.”

agree somewhat, but his ideas and writings as art are interesting. I really like the actuality of realizations of LeWitt’s plans, though…

Oh, I like Minimalism. It’s the death drive incarnate. Repeat and crush and repeat and crush and repeat.

Nothing subjective about it– that’s the whole point. To an extreme that renders their quaint ideas about absolute materiality charmingly fanatically eccentric rather than (as some contend) oddly semi-fascistic.

I like the empowerment of the art critic in that article though, since I’m a bit of one of those.

“Repeat and crush and repeat and crush and repeat.”

Good one

but minimalism was all about humanism

/maybe that’s a lapsed fascism jk

their mystical not about communal power .. it about essential beauty .. identifying basic forms as joyous forms

“party LAN line”

// this is my favorite article //

Hmmm. One could see Minimalism being about the Golden Mean turned into a steel materialist coffin, or, alternately, about Heideggerian relationality retooled as techno-grid, so sure, those are humanist. And Minimalist pieces are frequently hilarious to boot– I kind of think it’s the funniest art movement of all time.

Fluorescent bulbs! On the wall! Staggered algorithmically! Pay me lots of money! Give me tenure!

Bert,

i’m thinking more of proto-minimalists like Piet Mondrian and peripheral figures like Agnes Martin

but i like your examples too!!

i agree that minimalism can be funny. Richard Serra for instance. maybe not hilarious, but witty, yeah definitely

Dia: Beacon

as

Laff: Riot

who is saying pay me lots of money? do you want lots of money?

click my name for some assistance in this matter!

Tee hee! No offense, that just sounds like an amusing online spam pickup line. Amusing until I get sold into white slavery.

I was thinking of Dan “Flavor” Flavin (who sells light bulbs for a considerable profit), and Richard “Lava-Slinger” Serra, whose sculptures occasionally kill people, as well as Carl Andre, who occasionally kills people who happen to be Ana Mendieta.

Sol LeWitt is the Soul of Wit– like circling every instance of “the” in a book, or connecting places he lived on a map. or Moire pattern Op Art with juxtaposing grids. Those guys kill me. Especially if I’m Ana Mendieta.

Serra is an asshole.

Just ask the hundreds of thousands who have to detour around his Fascistic sculptures.

Um… Tilted Arc was taken down like thirty years ago. I imagine people are over it. I’m sure there’s a Chipotle there now.

It was a major piece of assholitude in its time, anyway. Fuck that jerk up the poop chute. He’s got his tyrannical crap all over the planet by now.

I like his asshole pieces the best. It’s moves like that that make avant-garde art art.

And he’s not a multinational franchise or anything, but lately he has made some cutesy giant toruses thaAt I’m not too crazy about.