By James Romberger

Thought forms in the mind as a combination of word and image. For that reason, cartooning is a direct, intimate means to communicate subjective thought to a reader. This is why many of the greatest comics are by artists who write their own narratives. Still, it is rare that a single person can both draw and write well, much less produce a work of blinding genius; one can spend a lifetime mastering either discipline. However, a writer’s words can be brought to life by an artist of the prerequisite abilities, one who can accomplish what in a film might require an unlimited budget and even pass beyond, to the unfilmable. The comics form offers infinite possibilities to writers and artists who are willing to work together. But the focus on autonomy in alternative comics has left collaboration largely in the hands of comics’ mainstream, where it has been greatly influenced by the economics and labor/management relationships of periodical publishing. The reader’s indulgence is asked for a short history of those relationships, as a prelude to an explanation of the artist’s contribution to the collaborative process in comics.

Bullpen variations

“Bullpen” comic book production was initiated in 1936 by groundbreaking cartoonist Will Eisner and his partner Jerry Iger to meet the rising demand for content in the new medium of the comic book. Studio staff was divided into an assembly line of piece-workers: writer, penciller (which might subdivide to layout, character and/or background artist), inker, letterer, and colorist. The bullpen became standard for comics because it was expedient to publish books on time and made it so no one creative person was wholly responsible for, or entirely invested in, what was claimed by publishers as properties done by “work-for-hire” employees. Comics history is crowded with “ghost” creators like Carl Barks and Bill Finger, who worked in near or actual anonymity and were not compensated fairly for their contributions. For many years, that was the accepted status quo.

In the early 1950s at E.C. an odd exception to the standard sweatshop mold led to some of the best comics published to date. Editor Harvey Kurtzman recognized that in comics, the crux of storytelling is in the layout or breakdown that integrates text with image, the pencil drawings that establish the structure and style of the design. The layout finds the flow of viewpoint and character interaction. Kurtzman made articulately composed page diagrams for all of his stories with every basic element drawn roughly in place, which his artists then rendered to finish. Still, individual stylists like Wallace Wood and John Severin did some of their finest work for Kurtzman’s war comics “Two-Fisted Tales” and “Frontline Combat.” Kurtzman demanded a high degree of accurate detail for period stories; his artists respected his guiding intent and invested their drawings with research, observational realism and great passion. Kurtzman also grasped the importance of color and worked side-by-side with colorist Marie Severin to enhance his narratives immeasurably. In these atypical collaborations, Kurtzman was the writer and also the primary storytelling artist. His finishing artists acted more as elaborators, but it was they who signed the stories, Kurtzman only took credit as editor.

Another version of the Bullpen was introduced with what became known as the “Marvel method” in the 1960s. Editor Stan Lee enlisted artists such as Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko and Gene Colan to draw their stories from brief plots outlined by Lee in a short note or phone call, or to invent the stories from whole cloth themselves and make notes that described the narrative and suggested dialogue in the page margins. After the fact, Lee added captions and balloons based on those notes, in his words a job often “like filling in a crossword puzzle.” Lee was able to do this because on their own, these experienced storytelling artists could initiate and motivate characters, construct their environments and produce complete comic book page sets. For what often amounted to copy-writing, Lee claimed full writer credit and pay. In this arrangement, the pencillers were also uncredited plotters and co-writers.

Jack Kirby writes continuity, which Stan Lee ignores, from the original art for Fantastic Four Annual #3, 1963

In particular, Kirby was the single greatest driving force in the foundation of Marvel’s popular multimedia empire; his creative input on “The Fantastic Four” alone encompassed a multitude of imaginative characters and settings. To be fair, Lee helped make the books successful with his unifying voice; in the letters pages and in his “Bullpen Bulletins” he created an illusion of family that resonated with young readers. He did plot and write some of the stories and he credited his artists (for their art) prominently. But Lee also failed to defend his collaborators’ interests to management. According to Kirby biographer Mark Evanier, promises were made to Kirby about royalties that were not kept and Kirby found no one to address his concerns to but Lee, who said, “I have nothing to do with that.” Kirby subsequently left the company rather than be further exploited. Kirby’s children still struggle to gain any portion of the multibillions Marvel makes from the comics, films and merchandising derived from their father’s work.

Too many battles were fought by the artists and writers of comics for their rights to be detailed here, but in the early 1980s, major publishers instituted “creator-owned” contracts for special projects in which artists and writers share copyright as co-authors, on an equal footing. Mainstream comics are still closely overseen by an editor, who selects teams and then acts as intermediary to writer and artist, even in creator-owned projects. The editor can facilitate their best efforts and contribute greatly to the storytelling by honing the creator’s individual contributions, depending on the sensitivity and sensibility of their recommendations or dictates. Some other holdovers from the bullpen days are still present in mutated form. While some artists finish their own pencil drawings in ink, others still have their pencils inked or finished by other artist. Inexplicably, though color makes a profound impact on the reader, the colorist still holds the lowest-paid job in comics. Perhaps as a consequence, few artists in comics do their own color, which is now most often applied by digital artists, with mixed results. Also, while alternative cartoonists often prefer to letter in their hand, mainstream artists do not and digital fonts have supplanted hand lettering almost entirely, not least because digital balloons and captions are editable until the last moments before publication. Whatever the rationale for their use, digital typesetting loses the qualities of illumination that are an important advantage of the comics form. Inkers, colorists and letterers of varying degrees of skill and artistry can greatly enhance, or ruin a book. But, it should be reiterated that the penciller controls the layout and storytelling and so is the primary artist.

Make It So

Currently in mainstream comics, an editor works with a writer to provide an artist with a document that resembles a movie script. This text describes the settings, the personalities, speech and actions of the depicted characters, as well as the trajectory and intent of the scenes. However complete this may sound, it’s not; the artist’s job is daunting. In a film, the lion’s share of the credit does not usually go to the writer, but to the director, the person in charge of the product of a largely visual medium. In comics, the artist must engage complex skills that approximate everything that would be involved in making a movie: direction, cinematography, casting, actors, production design, set design, lighting, costume, makeup, special effects and every other function, including that of the person who tapes around the actor’s feet to mark where they were standing.

One challenge for the cartoonist is that one’s “actors” must play their parts with well-timed reactions and believable emotions, expressions and gestures. That is no small feat of itself. The characters must reflect the diverse variability of human form. They must also be recognizable (“on-model”) from all angles or lines of sight, as must the settings, objects, vehicles and fashions, which also must all be true as possible to the time and place depicted, down to the smallest necessary detail. All of the depicted persons, environs and objects must also be executed in perspective and reflect the influences of light and the natural elements. In other words, the artist must understand and render everything that in a film is recorded by a cameraman. Like animators, cartoonists visualize movement within three-dimensional space as they simulate the viewpoint of a weightless steadicam; they engage a complex form of draftsmanship that can be described as “motion perspective.”

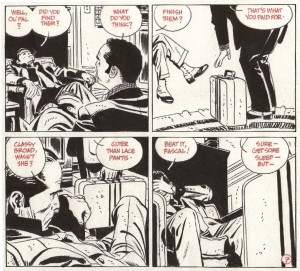

Alex Toth, motion perspective from the original art for “Torpedo.”

Quintessential moments must be chosen to freeze in panels. A further complication is that the characters must be composed in each panel in their order of speaking, as indicated by the script. The refined composition of each panel acknowledges not only the design of the images viewed simultaneously in direct proximity on the page and on the facing page (a two-page “spread”), but also those throughout the entire narrative. The illusion of movement occurs in the spaces between panels, where positive and negative space flip, creating visual rhythms that sync with the beats of the broken-down blocks of words, as the reader’s eye is led where the artist wants it to go. At the layout stage, artists might expand upon, or deviate significantly from a script in order to make a story work effectively. For instance, the addition of panels can serve to compress time or make actions clearer, captions can be bumped to panels behind or forward in order to gain room for a larger drawing, captions can be added or deleted to clarify character. In truth, it would be difficult if not impossible to find a cartoonist who did not add many acting characters, objects, architecture, flora and fauna of their own device throughout the execution of a given story, all of which contribute substance to the narrative.

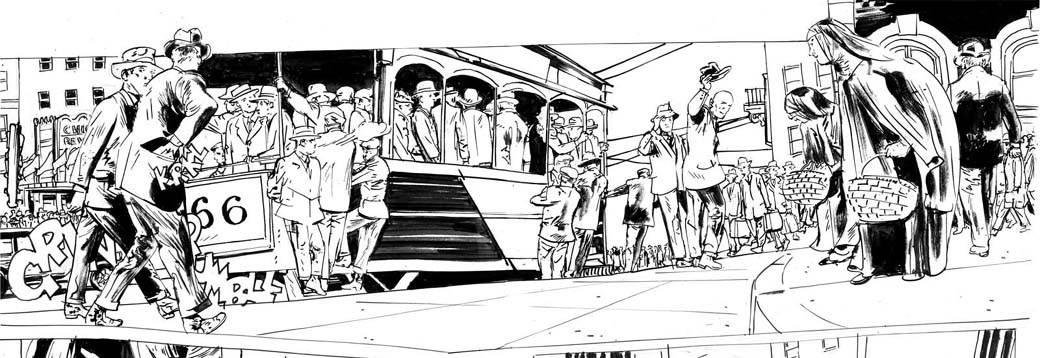

Artist Tony Salmons notes three seemingly innocent words often seen in scripts, “a crowd gathers.” Salmons says, “A writer scripts or merely plots this line down on paper and goes on to the next scene. I spend an entire day researching, casting, lighting and acting out that crowd. Is it an opium den? SF or Hong Kong? Texas? German beer garden? Rainbow room at 30 Rock? What kind of crowd? If I do it with total commitment the considerations can go way beyond this. And the writer’s contribution is 3 words, ‘A crowd gathers.'” No matter what the story requires, the artist must make it so.

Tony Salmons, detail from the original art for “The Strange Adventures of H.P. Lovecraft.”

Additionally, ideas occur in the process of drawing. The artist may see a better way to articulate a scene after it has been laid out, when the story has achieved sufficient form that new visual potentials emerge. Artist P. Craig Russell has detailed one of the artist’s many unique contributions to comics storytelling, a technique he aptly calls “parallel narrative,” sequences invented by the artist that diverge from the script to depict scenes that are not in the text, that are intended by the artist to counterpoint the text. In comics, the onus is on the artist to make the story work. For that, the artist must find ways to “believe” what they are drawing, to feel the motivations of the players, the touch of a lover, the heat of battle or the cold night wind of the desert and express them to the reader.

Comics demand an immersion on the part of the artist that goes far beyond the job description of an illustrator. Illustrations are derivative entities that are subordinate to text, isolated visualizations which can operate either as redundant to the words or as commentary on the words, ranging from literal to oblique. In comics, the text is most often visually subordinate. The images are imbedded with far more information than the words. The words represent sounds and qualify the images. The text need not say something that is clearly shown in the pictures. Illustrations can enhance or challenge the reader’s visualization of prose, but comics are a full-blown realization of narrative, with the intimate interactivity of a book and with more potential for expansive spectacle than film.

For most of comics’ short history, the writing was often the weakest element and so highly skilled interpretive cartoonists have longed to work with better scripts. As the graphic novel gains ground in the book trade, more serious writers will want to explore the form. This could result in more sophisticated and revelatory collaborative efforts. It should be made clear that comic artists are usually paid more per page than writers, but for as long as credits have been given, artists have willingly shared them equally with writers. But now, the equilibrium of credit has slipped askew. Increasingly one sees collaborative books credited and publicized with the emphasis on the writer alone. Such selective crediting causes further chain reactions. In the catalog listings of libraries and booksellers, the “Author” is listed first. In the case of graphic novels, it is assumed that the name credited as “writer” is the “author,” unless specified otherwise. The artist might not even be included in bibliographic data unless credited by the publisher as a “co-author.” Amazon’s default system for graphic novels lists writers as “author” while artists are diminished to “illustrator”, a subordinate creator and in no way a “co-author.”

This diminution of the artist’s perceived role in comics has repercussions for alternative and mainstream artists alike. Artist Jillian Tamaki spoke of her process collaborating on the graphic novel “Skim” with her cousin, the writer Mariko Tamaki: “(Mariko) was not precious about it. It was basically just a play and there was no description of what they were doing when they said something, or where they were…it was me putting the pacing in, and the rhythms and the timing and the backgrounds….it took about two years.” But when “Skim” was nominated for a Canadian book award, the writer was the only one cited for the honor. Writer Alan Moore makes sure that his artists share equal credit, but Neil Gaiman’s name dominates the cover of the exquisite book P. Craig Russell made of “Coraline.” It can and has been claimed that it is Gaiman’s name that sells books, but a case can also be made that Russell’s mastery of the comics medium is such that his adaptations of Gaiman’s prose stories are more resonant in their form than the comic books that the writer has scripted. Even as the medium is poised to evolve into a sophisticated art form, critics often closely analyze what they perceive as “the writing” of a given book, but ignore or barely describe the art, perhaps because they are unaware of the interrelativity of text and art in comics, or perhaps because the publisher’s packaging and promotion tells them that the writer is the primary creator.

This trend will discourage thoughtful non-writing or interpretive artists from involvement with the medium. Because of the labor-intensive nature of comic art, a graphic novel can take an artist years, even decades to complete. In the current climate, collaborative comics become much less worthwhile for the artist. The remedy to this situation falls to the individuals who work in comics. Artists should avoid the “illustrator” label and stipulate a co-authorship credit for themselves in their contracts. They might find that there already is a co-authorship stipulation in their contracts, which has not been honored by the publisher’s packaging and publicity arms, or that there is some ambiguity in the distinction between “co-creator” and “co-author,” or they could discover that there is a contractual clause which calls for “credit according to current practice.” This means that the more artists allow themselves to get less credit, the more it becomes current practice. Also, writers could heed Alan Moore’s positive example and not allow their credit to override that of their partners. Both creators should ensure that their publishers direct their design and promotional departments to incorporate the contractually stipulated credits and see that book trade entities correctly list them. The alternative is that artists accept a diminished role and lose their hard-won rights.

In the end, the credit issue is about more than just the bruised egos of artists and writers. Debates about the validity of authorship itself are set aside when the realities of book publishing and movie deals come into play. A great comic need not ever be made into a movie if it resonates sufficiently within the parameters of its form, but when films are made and when book royalties accrue, artists and writers should share in the credit and proceeds as co-authors. For the artist, comics are a difficult form and the work involved in a graphic novel is not undertaken lightly. If his or her contributions to the whole experience of reading are seen as expendable tools of the writer, the evolution of comics is at risk.

Sources

Jack Kirby scan courtesy of the Howell-Kalish collection. From the Jack Kirby Museum’s Original Art Digital Archive.

Evanier, Mark. Kirby: King of Comics. New York: Abrams, 2008. p. 157.

Green, Karen. Words and Music…er, Images. Comic Adventures in Academia, column on Comixology website, 4/3/2009:

http://www.comixology.com/articles/212/Words-and-Music-er-Images

Lee, Stan with George Mair. Excelsior! The Amazing Life of Stan Lee. 2002. New York: Fireside/Simon and Schuster, p.146.

Russell, P. Craig. Parallel Narrative. Video series posted online: www.pcraigrussell.net

or http://vodpod.com/watch/1296908-pcr-tv-parallel-narrative-murder-mysteries-part-1

Salmons, Tony. Quote from private correspondence. August, 2010.

Tamaki, Jillian. Quote from transcript of panel discussion: Inside Out: Self and Society in Comic Art. Moderator: Calvin Reid. St. Mark’s Church, Howl! Festival, 9/10/2008:

http://www.comicsculture.net/

A great post, James.

I think it’s very necessary to remind us all about the nuts and bolts behind comics creation. Moreover, with no ill-will at all, blogs or mags such as HU tend to be slanted towards writers, simply because writers post here.

You are too much of a gentleman (and too averse to complaining) to mention that you, yourself, are the “victim” of this writer-centric attitude; (James’ excellent graphic novel for Vertgo, “Bronx kills”, has on its cover the scripter’s name in much larger typography than the artist’s, i.e. than James’.)

Curiously, in France there is an opposite prejudice. If Jean Scripter and Pierre Artiste produce an album, it will invariably be cover-featured as “par Pierre Artiste et Jean Scripteur”. The cult of the drawer still trumps that of the writer…as used to be the case in mainstream American comics, before those Brits (Moore, Gaiman, Morrison) turned the scripter into the superstar.

PS– I hope you post on this blog again.

Yes, to both of Alex’s points. I have been shocked (shocked, I tell ya!) by the big boldy headlines used to announce the writers on the Vertigo Crime series and the vastly diminished font sizes used for artists. In the case of BRONX KILL it most definitely should have been reversed (I’m just sayin’).

alex, what you describe as the french practice actually depends a lot on the publisher. dupuis for instance does have a strong tendancy to place the emphasis on the artist (but then, arguably, they are belgian). but dargaud (which is french) tends to do it the other way (i have a blueberry book right on my shelf, which says: “texte de charlier, dessins de giraud”).

& actually, even at dupuis, there are localised exceptions, see for example tome & janry, yann & conrad, etc. so it’s really not as systematic as you say.

In the interest of true confessions and generally embarrassing myself, I should note that this post came about originally because I was guilty of leaving James’ name off the teaser post for (I think) Bronx Kills which I put on the main site. James justly chastised me…but was then kind enough to expand said chastisement into this post….

Thanks for more history, I always learn something.

At SCAD c. 1997-2003 we learned basically each individual job as a foundation and then had some opportunity to put the pieces together (I think the methods there have advanced since I left). This approach usually preserves autonomy, but provides for discovery of wich job you are more attuned to, so you can sell yourself to DC, Marvel… The autonomy is not as pure I would guess it is at CCS (which I think has much do do with Sturm leaving and making it). I would guess it might have more at Kubert. It is unusual to build relationships at SCAD that result in collaborating futures. I think we all like the idea of it, but to invest in someone else’s success when yours is virtually nil, is a huge leap of faith when you know you can adiquitly go it alone with the same results.

Since receiving two degrees in Sequential, I discovered the real challenges of autonimus cartooning has much to do with the fast paced modern world, the lack of economics, and the paralizing effects of working in an isolated environment, the voices in your head left by past critiques and the success you hear of by your piers.

Since graduating, and even during my time in Savannah, I have spent years developing ideas that never got beyond a plot, few pages of script, a thumbnail outline, a character design, a list, a drawing. For a brief time I produced consistently, then spuraticaly a page or two. Then last year through now I have managed to eek out 10 pages I am proud of, but will no doubt live in obscurity or if lucky, critical purgatory.

I rarely consciously give your point credit in these abysmal results. While I cartoon by myself, I am also paralyzed and disabled by my past and current strugles with English. A result of Dislexia, confidence, interest, impasiants, and thin skin. Lucky for me cartooning takes 80% of your effort in illustrating visual storytelling. Which is why there should never be this argument about rights and royalties (it took cartooning for me to get how screwed Kirby was). But it is during the writing side technically that I am most likely to ruin my comics. And it is also related to my lack of reading literature which has limited my storytelling abilities. My strength in the visual has resulted in an influence on my work being primarily life, secondly comics, thirdly motion pictures and hardly at all novels. This admition should not undercut the relevance of my frustration with the critiques here that overly value writing…both in terms of accepting some illustration and in terms of grilling the writing and storytelling from the perspective of another medium. Thanks for pointing out that flaw here, of which there are few.

It took me 6 years since school to produce work I am happy with. Work that virtually no one reads. Work I may get paid for in a decade or so. Work that faces realistic odds of never surviving when held up to the criticism I myself place on others, let alone the criticism seen here. Work that is the result of me creating more hours in the day then there are, because of my commitments to things that actually mater like, wife, child, day jobs in the medical and educational fields. Nevertheless, I consider the life long (since age 4 I have been trying and thinking about comics cartooning daily) journey a success for my work in school and the last 10 pages I have done. This rate of production will improve, and the quality will as well, but writing will always be my Achilles. And visual storytelling is hard enough. You would think I would be trying harder to collaborate.

My cartoonist story is just as relevant and valuable as the story of cartoonist in sweetshop without credit or compensation, or the flash in the pan that results in a destitute life. Notable success in comics is like winning the lottery, with acceptation of it requiring connections (I have a couple thankfully), people skills (so you don’t ruin your connections…which I question if I have), illustrative and design talents, writing talents, storytelling talents, a good story and time, time management or the life of Old Ben (lots of time and no life). If you have 6 or so of those your name is accompanied by genius. It would be nice if us hardworking stiffs got some credit or cut some slack from time to time.

Man sorry for going off. Honestly, we do it for the love of comics, as do you and us all. There might be one or two thoughts worthy of this interesting piece.

Good luck with your cartooning, Ben. Perseverance seems to be the key.

RE Ben Cohen comment

“But it is during the writing side technically that I am most likely to ruin my comics. And it is also related to my lack of reading literature which has limited my storytelling abilities. My strength in the visual has resulted in an influence on my work being primarily life, secondly comics, thirdly motion pictures and hardly at all novels. This admition should not undercut the relevance of my frustration with the critiques here that overly value writing…both in terms of accepting some illustration and in terms of grilling the writing and storytelling from the perspective of another medium.”

I think Ben just nailed what I sense from most young kids who are trying to break into comics – there is this silent rage undrneath them because they know that they need collaborators or have to re-wire themselves to “write”.

There are of course types of comics where you don’t have to have much of a narrative but then that’s “art comics” and you aren’t going to make much money.

This is precisely the crisis I think for alot of kids. They feel

trapped. They are talented but they know that it’s gonna take a writer or a total overhaul OR just doing arty stuff.

I see it all the time. Then these kids either do arty stuff and do it

well or they wither away and you never see them again. They drop off the radar. They realize that they just have to hang in there and it’s a long, long slog.

Hey Frank. Thanks for dropping by.

It’s interesting — I think breaking into any art form and being successful is really hard. But the quality or content of the frustration must be different from art form to art form. I can see it being particularly painful in comics to be almost-but-not-quite able to do it yourself, so you can see the promised land but not get there (as opposed to film, for example, where you have to know going in that you need a lot of other people to realize your vision.)

And of course comics aren’t very popular, so fewer people can succeed….

I just realized that the same is true for alot of kids who strictly do collaborative work – who try to break into Marvel or DC. They’ve really only drawn other people’s characters forever and don’t know how to create something of their own.. well, let me re-phrase that – something of their own that is not just a re-hash of an established character – and it’s a funny thought or a terribly sad one – that on both sides of the fence, it’s the artists who won’t or can’t write their own stuff that really suffer. I think the frustration is reinforced by the assembly line style that comics is used to. That’s why comics schools suffer because there is no way to fairly set up a workshop. Each student wants to be an auteur. No one wants to be “just” an inker or “just” a colorist. But in the real world and the real world sub-contracting workplace that is the deal.

Don’t have the time right now to read, much less deal with, this weighty commentary.

But, that sure is a strange choice of art to illustrate “Jack Kirby writes continuity, which Stan Lee ignores, from the original art for Fantastic Four Annual #3, 1963.”

In the second panel, Jack writes on the margin that ripping up the paper “hurts [Dr. Doom’s] hands and makes him angrier…He’ll get even.”

Considering that Doom was wearing armored gauntlets, this was surely a joke rather than a serious direction for Stan’s scripting to follow, no?

Mike…I think looking for logic in one of these comics is probably a bit beside the point. I mean, if cosmic rays make you stretch, why can’t you hurt yourself on paper through metal gloves?

Frank, maybe, as James sort of says, a good bit of what you’re talking about is probably related to the shittiness of work-for-hire, and how thoroughly it’s dominated the industry? That is, success in a big way for a lot of people means working at the big two — but if you do that you’re in a situation where you are working on an assembly line with somebody else’s characters. The path to individual success is really unclear. Maybe there are more options now, but I can see how it would still look pretty stifling for a lot of people.

Yah, I realized I just parroted James after I typed in that friggin captcha code – my bad – but yes, shittiness in work for hire. Unfortunately shittiness in work for hire situations is often better or preferred than unemployment, cynicism and bitterness of lonely drawing table and blog done for free, no?

Oh, absolutely. The unique thing about comics is that the work for hire shittiness is — not the only game in town, but still more of the only game in town than in most other mediums.

Though other mediums can be terrible too. Music industry contracts are legendarily horrible (there’s that great article by Steve Albini comparing signing a record contract with swimming through a pool of shit.)

The internet has changed things around to some extent…but doing a blog for free still is still kind of the alternate option, and obviously that’s not appealing to a lot of people….

Alex, Frank: At 35, all I know now is perseverance. The dream has changed. Now it is having a body of work that I am proud of, that can be piled in a thick book I can hold before retirement age. If there is more to it then that, something incredible happened along the way. Gone are the shelves of work, just a book is left.

Frank: I am constantly changing my approach, not because I am unaware of better ways, but because I know I am limited. I am a very eclectic and balanced person, so I have struggled with limiting what I do. I want my work to reflect myself. Which it does in limitations, but not in all aspects of my thoughts. I am not able to stick to one mode and be satisfied.

I am highly respectful of those who are satisfied and skilled at one aspects of comics. I think of them as Zen masters. I wish I could be ok all the time with just inking. I love it, see it as not just technical, but the time I really feel I am cartooning. It is like knowing a secret when you ink something well.

Schools have very little time to put all they need to into a student. And much of the time you are striping away bad habits instead of instilling skills.

I should amend something I said, I was listening to Eleanor Davis interview with Ink Studs today and was reminded of the close working relationship she has with Drew and a few others. They came right behind me in school at SCAD and had figured out things my class seemed to miss in terms of collaborating.

Noah: As an art teacher, artist in multiple disciplines (cartoonist are naturally so), and art student I have found the differences in challenges from art form to art form fascinating and very telling of the artist as a person. My wife and I are quite different. As a Jeweler her risks are based in limitations of editing opportunity. If she messes up something, that’s it. With her materials cost this is a huge oops. With mine it is the limitless resources, editing, elements that cause stress. A complexity that challenges on equal levels, in very different ways.

The financial reality has resulted in me, treating my carrier choice like a hobbie. But this has freed me artistically and allowed me to live a life away from my drawing table that informs my work with better perspective. I think in the end, I will be satisfied.

Alex and Jared: Thanks. I have to note that my name is HUGE on the cover of Bronx Kill, but yes, Peter’s is that much bigger. Vertigo did restore the artists’ name to the spines, after it was pointed out that the spine is what is visible in bookstores so the artist was basically rendered invisible. Vertigo does deserve a lot of credit for raising the bar for writing in comics with Morrison et al.

About the European crediting, I’m not expecting anything other than equal credit with a writer. As to who goes first…um, how about alphabetical order?

Ben: Without giving you my entire life story, ha ha, I went to SVA for a few months in the early eighties and could have studied with Eisner and Kurtzman, but chose not to. At the time, I felt that comics were something you learned by doing and by studying the actual work of the masters….and by studying the masters of fine art and literature as well. I think I still feel that way. Studying comics alone is misguided. The idea of going to Kubert’s school and learning templates for storytelling, or learning to draw the “Marvel way,” well, as Toth would have said, not my cuppa.

Anyway, cartooning is a lonely profession and takes a lot of dedication. Its amazing that the younger creators are training themselves to both write and draw, mostly without the benefit of page rates. And they keep getting better. They have it worse than the bullpen guys, in many ways…no paycheck to speak of, if at all…but at least there’s freedom. You are in charge of yourself and maybe I’m an optimist but I do believe quality will out. More anthologies would be welcomed for people to hone their chops on short stories. I’d also like to see more collections like “The Book of Other People,” where short comics narratives coexist with prose stories.

Frank: I’d like to see more collaboration in the alternative/literary zones of comics. There are certainly other ways of working than only solo acts, and enough public interest in the form to justify experimentation.

Mike: without going too far down this road, the point of that was that Jack was aware that the last time the FF met Doom, the Thing had crushed his hands, since, it seems, he pretty much wrote it. Kirby gave Doom a motivation, that even ripping paper in metal gloves made his hands hurt so much that it fueled his desire for retribution. Stan would often gloss over the deeper meanings that Jack would put into his stories.

Finally, thanks Noah, for giving me the opportunity to try to organize my thoughts.

Excuse the life story. And I am known for securities routs in life.

I understand that argument and would not deny it’s success.

It is clear that great cartoonist often have no formal training, reject their art school background (Clowes!) and I have had this advice given to me countless times.

I spent my childhood and the first four years of my adult life cartooning on my own (with some quality general art foundations). And yes, understanding comics was preserved by the Marvel way video. The results were pages that were no where close to on par with my contemporaries (like Tomine). So I ended my college dropout status and went to SCAD. I did around the last year of my undergrad, begin to see real results. It could have been enough.

However, I asked James Sturm for a letter of recommendation to return for my masters. And he of course discouraged this approach. Saying what you said…cartoonist are better served out on their own. Of course he gave me the letter anyway.

I returned to SCAD after three months of freelancing at the end of the dot com bubble. My first year was plagued with poor performances, buckling under pressures applied by myself and Professors. As far as we know I was the first person to do this double Sequential Art degrees. But by the end of the year I turned a corner and am convinced that second year and this past year and a half are my best periods so far. I credit myself, my wife, my professors and the talented classmates I learned with in creating the highlight of my cartooning education. I am not alone in missing that environment to cartoon. It was as close to the bullpen as I have gotten. Now living in a rural community, I often have long bouts with not cartooning. I would say lack of other cartoonist around me is a huge part of this weakness.

Many argue for liberal arts education for cartoonists. In art school I advocated for more liberal arts, science and math courses. I valued art history mostly for the broader historical context, philosophical questions ect… I took existentialism, psychological realism in literature, and language, culture and society. Anything I could to broaden my view. This is an area that is weak in Art Ed and needs better focus in all disciplines, not just storytelling ones.

The two primary weaknesses in cartooning schools are the curriculum and the teachers. Going to teaching school, I learned two things that not all art teachers know or embrace…YES! I like being in class. Anyway, I learned why we NEED to learn art and I learned how to assess and motivate individual students. A brilliant cartoonist is not the same as a brilliant teacher and one curriculum does not result in facilitate success for all students. It use to be that learning how to teach was a bogus effort, but I would argue that teachers who understand how their students work, what their strengths and weaknesses are and how to utilize them in pursuit of the objective can produce superior cartoonist to those who are left to their own devices. But even this approach does not guarantee genius and a genius may of course be better left to their own devices.

I admire greatly SVA’s program.

Good for you, Ben, and here’s to your continuing success!

Ben, believe me, I don’t mean to disparage education in any way. My feeling is that going to school exclusively for comics is a mistake. Artists and writers should also study the history of art and literature, the sciences, etc, in other words have a rounded education, so one can bring more to the table than what has already been seen…the medium would be better advanced by people with a larger reservoir to draw from. In trying to keep my focus relatively narrow in my piece, I neglected to mention the other, barely tapped potentials for comics, such as the diagrammatic qualities seen in Ware for instance, or areas outside of entertainment… comics are a tremendous tool for organizing information.

We agree and the path to being someone who can reflect the world with form and function inovativly through comics does not require cartooning school. However, the educational setting at most schools have advanced enough to make it an advantage. They do encourage and provide the opportunity of being well rounded. But it is not forced, and requires a hunger on the students part. So in other words it’s no garentee.

I think there should be cartoonist’s circles, just as there are writer’s circles.

Alex-

In Seattle, there are no less than two! Check out bureauofdrawers.org, the website for Bureau of Drawers. I know of at least one in Minnesota as well.