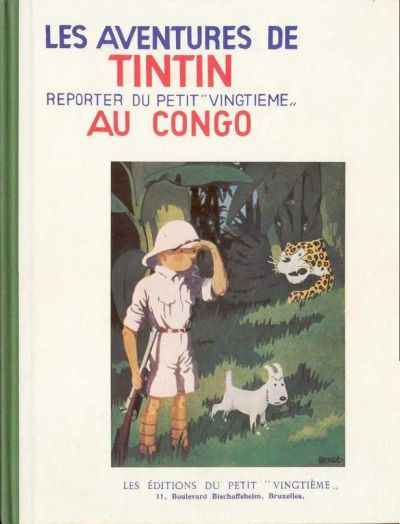

The children’s comics album Tintin au Congo, by the Belgian cartoonist Hergé, has been much in the news of late– and not in a good way.

In Britain, the Commission for Racial Equality has condemned the book’s “abominable” racism (and proving once more that there’s no such thing as bad publicity, its sales have jumped 5000% on Amazon UK). It’s been banished from the children’s section in bookshops and libraries across America and the UK, in chains such as Border’s.

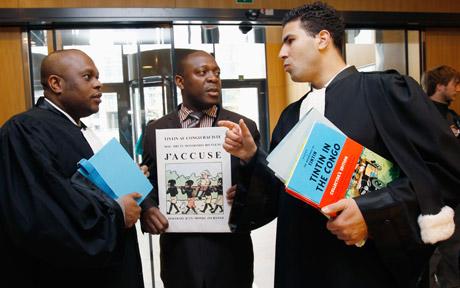

Finally, following a lawsuit brought by a Congolese student, Bienvenu Mbutu Mondondo, a court in Brussels is to determine whether the book should be banned in Belgium. Similar lawsuits have been brought in France and in Britain.

So: just how racist is Tintin au Congo?

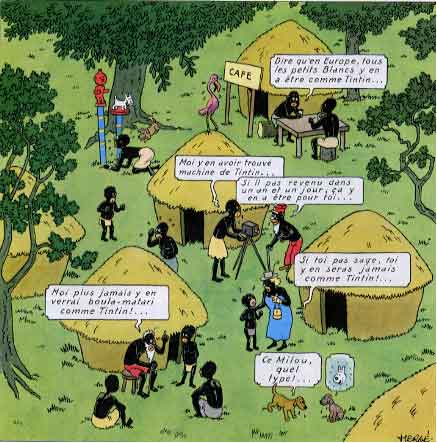

“And to say that in Belgium all the li’l Whites are like Tintin!”

“Me find Tintin’s machine…”

“If him no come in 1 year and 1 day it for you…”

“And if you no be good you’ll never be like Tintin!”

“Never again me him see a boula-matari [stone-breaker– the title given to Stanley, the white, conqueror of the Congo] like Tintin”

(Dog) “That Snowy…what a guy!”

Note in the upper left-hand corner: fetish statues of Tintin and Snowy before which a Black man kneels in worship.

I could post many more cringe-worthy excerpts, but why bother?

Yes, Tintin au Congo is racist. Whether it should be restricted or banned is a debate I’ll leave to others, although I certainly wouldn’t allow a child of mine near it.

“So what?” the informed comics reader might object.

It’s no new discovery that throughout comics history racist and bigoted content has permeated the art form. The Imp in Little Nemo:

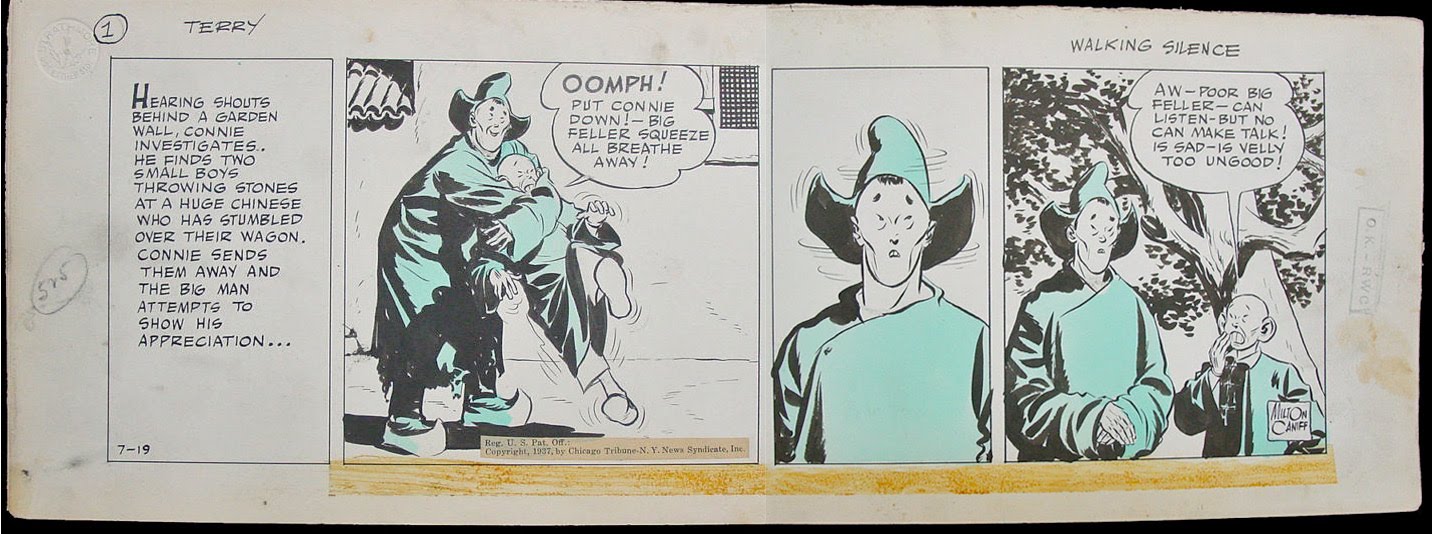

Connie in Terry and the Pirates:

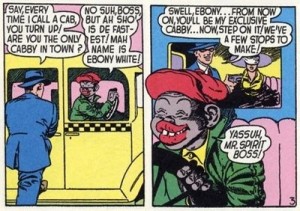

Ebony in The Spirit:

The first appearance of Ebony White; art by Will Eisner

…the list of offensive stereotypes is endless.

One balances a historical approach with a rejection of such inadmissible values, and one moves on.

But the case of Tintin — and of his creator, Hergé — warrants more thought.

First, unlike the vast majority of popular comics with racist elements, Tintin remains relevant.

The series of 23 albums has sold, to date, over 200 million copies in sixty languages and still sells briskly. It has spun off magazines, toys, television shows, feature films; Stephen Spielberg is now in post-production of a blockbuster adaptation of The secret of the Unicorn. Tintin isn’t enjoyed only by middle-aged fans, either; children respond just as eagerly to his adventures today as they did eighty years ago.

So a certain level of scrutiny is justified, simply because of Tintin’s effect on the culture, and on young minds in particular. Tintin au Congo is the most egregiously racist, but most of the other albums have disturbing aspects as well.

I’m interested in Tintin’s racism, xenophobia, and general fear of the Other for different reasons.

Tintin changed over the years. By which I mean that the individual albums were redrawn, rewritten, compressed and otherwise redacted, some more than once: L’Ile Noire (The Black Island) exists in three versions, from 1938, 1943, and 1965.

And in these redactions, the racism has been drastically toned down. Take this example, from (top) the original, and (bottom) the revised versions of Le Crabe aux Pinces d’Or:

And the above shows why I speak of a toning down of the racism, not of its elimination. The caricature of a brutal black is replaced, true – by the caricature of a brutal Arab.

Note that the above change was not made at Hergé’s initiative: it was his American publisher, Simon and Schuster, who demanded it (as well as the ‘whitewashing’ of four Black characters from Tintin in America. ) As Hergé sardonically remarked,

“What the American editor wanted was the following: No Blacks. Neither good Blacks nor bad Blacks. Because Blacks are neither good nor bad: they don’t exist (as everyone knows, in the USA.)”

Thus a racism of caricature is displaced by a racism of denial.

Indeed, the revised editions function as palimpsests—and as with all palimpsests, the ghost of the original text is sensed. Or shall I make a psychiatric analogy and speak of the return of the repressed? Whichever — I find the tension between the clean images and cleaner morals of the modern editions, and the nasty energy of the originals, gives the strip much of its strange and seductive flavor; something subterranean, something I only intuited until I came face-to-face with the older, rougher, uglier incarnation of the strip.

But the other changes in Tintin over time were rooted in the personal evolution of its creator. He progressed from a narrow-minded petty bourgeois stuffed with the ignorant prejudices of his time and caste, to a far more generous spirit eager to engage the world—and the Other—as it truly is. It took him a mere forty years.

In the next instalment (Update: now posted here), we’ll review the background of Georges Rémi aka Hergé, and the shocks to his world that caused his long climb away from simple bigotry; and in particular his meeting with a young artist from China.

____

The entire Tintin in Otherland is here.

All art copyright Studio Hergé/Moulinsart.

The fetish statues of snowy and tintin are pretty brutal.

When was the revision to the brutal Arab made, do you know Alex? Was it 1943, 1965, or some other year?

You’re right that this deserves some serious scrutiny. But on the other hand, it’s really hard to measure the effects it’ll have on young minds.

From a personal example, I read Tin Tin all the time when I was little. Ate that stuff UP. There’s a sequence in one of them where Captain Haddock is trying to explain to a ship full of Africans that if they go to Mecca, they’ll be sold off as slaves, and the Africans are simply NOT getting it at all. I thought it was a hilarious sequence, but the message I got from it wasn’t “black people are completely stupid”, I just thought the good Captain god saddled with a particularly thick group of characters. I’m not saying that that was NOT a racist sequence, because it obviously was, but what I AM saying is that people should give kids a little more credit than they do.

It’s also interesting to see which cultures Herge esteems and doesn’t-his South American characters are close to abhorrent at points, but he seems to treat Chinese and other Asian characters with a modicum of respect-very few of them, if any, speak with ridiculous accents or broken grammar and many of his Asian villains are extremely capable. Of course, I haven’t read them in a million years, so I can’t recall their visual interpretations.

I think it’s pretty reasonable not to want to give Tintin in the Congo to kids. My son is aware of race (we live in a very integrated neighborhood), and he gets focused on minutia of plot and character when he reads Tintin. That stuff could absolutely come out when he was playing with a black friend, for example.

Kids aren’t any more programmable than adults are, necessarily — seeing a racist stereotype isn’t going to make them racist. On the other hand, people do use books and culture to process their world, and kids do that too.

I actually think it’s reasonable too, because the racial aspects are so deeply integrated into that story in particular. I wouldn’t give it to a child any more than I would show them some of those horrific old short cartoons from the ’30s and ’40s, because really, what’s the point? What’s to be gained?

I’m just saying that the “danger” of these comics is probably relatively minimal, even if they are reprehensible. Like…don’t show it to your kid if you can help it, certainly don’t go out of your way to give them something like Tintin in the Congo, but if they get their hands on it somehow or another it probably won’t be a huge deal. Certainly nothing a talk won’t fix.

That’s reasonable enough!

BTW, I dig the site, I’ve been reading it for a few days but this is the first article I’ve felt qualified to comment on. When the subject doesn’t totally fly over my head, I’ll be sure to chime in :P

Also, good God, what a dreadful emoticon.

Hey, Chris. I’m going to examine in part 3 the effect of Tintin on me as a kid. It’s good to look back sometimes with a cold eye.

I read all the tintin books (though not “congo”, and not “soviets”) multiple times from a young age. Then after many years break, I read them again, and was surprised at the smatterings of racism I found. I simply didn’t notice it as a kid. As weird as it sounds, my explanation for this is that without an adult reinforcing these images of black people by saying “that’s true; that’s really what they act like,” these pitch-black, absurdly outlandish figures were so different from any human I knew of that it didn’t affect me. What Herge meant to be comical served its purpose for me as a little kid, and it’s only years later that I can recognize the racism.

See Chris Jones’ first comment… the very scene I had in mind… I had no idea what “thick-headed, obsidian-pated scallawags” (or whatever) meant or implied, but it was HIlarious

Count me in as one of the children who didn’t see anything potentially racist about Tintin in the Congo. That last page of the mourning villagers could just as easily be from any country crying out from seeing their hero leaving. Tintin’s such an ubiquitous character that he can be identifiable to any nationality, no matter how big or small.

The interesting thing about that scene with the black man whipping Captain Haddock – even though he was whited in, the later dialogue where the Captain was drunkenly chasing him through the streets until he was stopped remains unchanged. He protests to a police officer to “Arrest that Negro!”, saying he beat him with a stick, and the cops who’d grown tired of his constant false alarms, decide to BEAT UP Haddock instead. Until I saw the original image in a Tintin history book, that scene didn’t have any relevence until I noticed.

Of course, this kind of whitewashing doesn’t quite work when the Black people are positive role models. It’s why there was such a general outcry over the cast of the Live-action Avatar movie.

I go into some interesting WhiteWashing of a certain children’s book in the second half of my blog entry here:

http://sundaycomicsdebt.blogspot.com/2010/04/smurfectly-smurfect-news.html

“I grew up reading that (Tintin) story, and never encountered any kind of racist thoughts. I’d argue that reading these kind of stories make us MORE open to black people, not less. After all, white humans get caricatured in every possible permutation in the comics page – why shouldn’t black people have just as many twisted features? *I* say keep experimenting with as many possible interpretations and find one that works.”

You find nothing racist about the statement “Never again me him see a witch-doctor like Tintin?”

This isn’t really innocent fun, here. It can’t be waved away as just taking the piss. This is a guy deliberately trying to make Africans, as a race, seem completely moronic and, if you read the rest of Tintin in the Congo, cowardly and superstitious, as well. That’s the very definition of racism.

Yeah; I’m sorry Daniel, but to say that Tintin in the Congo isn’t racist is simply ridiculous. Next you’ll be telling me that showing Jews contemplating ways to make a profit on the end of the world makes us more open to Semites, yes? After all, why shouldn’t Jews have as many twisted features as the rest of us — especially when those twisted features involve big noses and rampant greed. It’s not like that sort of thing led to genocide or anything.

Tintin in the Congo deliberately uses racist caricature to mock and degrade a group that suffered terribly at the hands of the folks doing the mocking and degrading. It is explicitly designed to justify vicious treatment as natural based on the cultural and biological inferiority of an entire people. As Chris says, it defines racism. It’s one thing to say that, in the present context, having a kid see is isn’t necessarily that dangerous or damaging — that’s a point on which reasonable people can differ. But to say it isn’t racist? That is promotes amity between white people and black people? That’s pernicious nonsense.

Herge isn’t “experimenting”. He’s using well-established, cliched visual and narrative traditions to portray black people in a condescending, viciously racist way.

Well, wait, maybe I’m misreading him but I don’t think Daniel was denying the racism in Congo. He’s describing his reaction as a kid.

Hmm; I guess that’s possible. The claim that it’s just experimenting though seems pretty hard to justify…..

Alex, you’ve pretty much got my interpretation dead on. I wasn’t going to contribute any more fuel to the fire if my comments were going to cause a never-ending debate between two opposing views. What I find interesting about Black caricatures is that so many of them are caricatured in THE SAME WAY. Large lips seems to be the dominant factor in portraying Black people.

I suspect my indifference to seeing European portrayals of Blacks comes from also reading plenty of Asterix comics, which had a solitary token Black in the form of the Numidian pirate who was part of the triumvirate of complainers whenever their ship went down.

Interestingly enough, Manga versions of Black people can go either way. They can either have Blacks similar to the Europeans caricatures, or they can be cheerfully blonde Ko-Gals. For some reason, fantasy Mangas usually have at least one influential Black character.

Hey Daniel. There’s a tradition of racist caricature based on blackface minstrel portrayals which goes back into the 1800s. The early 1900s, when comics were coalescing as a popular form, was one of the most racist periods in American history, which probably influenced Europe as well, and certainly had a long-lasting impact on portrayals of blacks in comics.

The wikipedia article on this topic is very good.

Yes, but what I was wondering was why, when compared to the various styles of other comic characters, do Black people get designed like the Blackface ministrel? If you look at the long history of cartooning, there’s a very varied difference of style between comic characters. Charlie Brown, Popeye, Dagwood, B.C., Hagar, Beetle Bailey, Broom Hilda, Dilbert, Dennis and Calvin all have their distinctive looks from each other. Yet when it comes to Black people, they have trouble distinguishing reasonable composites. That’s what I meant by experimenting – playing around with various doodles until they find something that works for THEM.

http://images.ucomics.com/comics/db/1993/db930101.gif

Some of the best portrayals I can think of include Lawrence from For Better or for Worse, Ginny & Clyde from Doonesbury, Marcus from Fox Trot (a Black nerd on par with Jason!), Ian from IanComic.

http://www.rpgworldcomic.com/iancomix/d/20001101.html

Interestingly, I see Kenji and Donkey from 20th Century Boys as Black, even though they don’t look so. This also applies to Aizawa from Death Note, especially when he developes an afro later in the series.

As long as we’re bringing up comparisions, Tsubaki from Hikaru no Go always reminded me of Captain Haddock:

http://www.onemanga.com/Hikaru_no_Go/79/02/

“Yet when it comes to Black people, they have trouble distinguishing reasonable composites.”

That’s called racism. They don’t distinguish individuals because they see the entire group as the same.

Daniel, I was interested by your link to your blog mentioning the “whitewashing” of the black smurf into the purple smurf. The Smurfs (Les Schtroumphs) were also a Belgian strip, like Tintin.

Hergé wasn’t at all alone in incorporating racist imagery into kids’ comics!

It’s a little late now, but I managed to find the French comic I was thinking of that served as kind of a more realistic version of a white reporter in colonial Africa.

http://scans-daily.dreamwidth.org/1262464.html

I take it from the above comments that it would be ok for captain haddock to be beaten up by a caricatured white Anglo Saxon thug –

But if anyone from another race or religion does it – well that’s racist.

That speaks more to me about the value systems of the people bandying about the accusation of racism than it does about a book that was written over 60 years ago when culture and values were very different.

It does make me wonder – do those that see it as their mission in life to root out every facet of what they declare to be racism from all the nooks and crannies of our past think it is only permissible to show Anglo Saxon Christians in a bad light or as the villains. That those from another religion of race can only be shown in a good light?

Or perhaps they feel that only white Anglo Saxons can ever be bad people. All the other races and creeds are perfect. indeed perhaps there never has been or never will be a black person who is a thug or a middle eastern who would beat another person as the one does to haddock.

But i hear you cry – ‘but these are stereotypes’ that’s why they are bad. Indeed. But it appears that a white thug stereotype is quite ok. It’s just foreign stereotypes that are wrong.

Interesting differentiation.

Funny – but bearing this in mind – i can’t help wondering – perhaps the real racism in all this is the racism that the racism hunters display themselves.

Have you seen the pictures from Tintin in the Congo? Have you seen Herge’s forays into anti-Semitism?

Alex talked a lot about the way Herge attempted to redeem himself and in fact repudiated many of his earlier racial stances. Do you think you do Herge a favor by pretending there was never any problem to begin with? On the contrary, you insult the man, the comic, and the effort he made when you attempt to (ahem) whitewash the past.

When herge drew these, there was still segregation in the US, open racism and antisemitism was common in Europe. Herge more reflects a society than his own personal views. It is in that context of that same society that came WWII with its atrocity, hollocaust, death camps… Possibly if the society had not been like that in the first place death camps would not have existed and Tintin comics would’nt have been so racist. The fact is that the world changes, and often changes more quickly than people, so Herge had to adapt and give explanations and change. I have seen similar antisemtic drawings in an Assimil “Russian” language learning book. The edition before 1950 depicts jews with big noses, etc.. the edition from 1960 has this drawing removed. Tintin is more famous so everyone noticed. But there is a whole lot of drawings and writings from that earlier epoch from Europe that is just plain racist. So it is really the society and I am glad it all changed. But yes, in the past people were racists, openly, in Europe. You wouldn’t go around telling you are Muslim or Jewish if you didn’t have to.

Yes, and the close parallel of Herge’s evolution, and that of society at large, is what fascinates me.

Chris Jones: No quarrel with your basic argument, but the details are based on a mistranslation of the original strip. “Boula-matari” does NOT mean witch-doctor; it is Kikongo for “Breaker of rocks,” the sobriquet applied to the explorer Henry Morton Stanley by the Congolese.

Well, that’s interesting. Stanley was of course the guy who opened up the Congo to Leopold II, leading to decades of atrocity.

This topic has been hashed and rehashed hundreds of times in the past 50 years in the French-speaking world. Every little bit of racism and prejudice was discussed ad nauseam with Hergé himself, who admitted he had led a very sheltered life until the late forties-early fifties. His upbringing was typical of the times: devoutly Catholic, intensely patriotic, pro-colonialist. He owned up to his sins of youth and made up for them as best he could in the remaining albums — although the true turning point for him and his worldview came much earlier, in the mid-thirties, when he drew “Le Lotus bleu” in collaboration with Tchang Tchong Jen. Think of John Lennon’s attitude towards women before and after meeting Yoko Ono.

Wanted to add that Le Petit Vingtième, where Tintin was serialized, was part of a right-wing Catholic supplement for Le Vingtième Siècle newspaper. He started working there as an impressionable teenager and was made by his publisher to send Tintin first to the USSR, then the Belgian Congo.

As for the anti-semitic elements, many (most?) came during the Nazi occupation of Belgium. Le Vingtième Siècle had been shut down; Hergé, wanting to continue making a living, was only able to find a (naturally) Nazi-controlled newspaper in which he drew daily strips for five years. Editorial censorship also forced him to vilify Americans in, for example, “L’Étoile mystérieuse”.

Hergé was very nearly tried as a collaborator after the war. Like tens of millions at the time, he was, if you consider anyone who did not join a resistance movement a collaborator. In matters of attitude towards race and religion, he seemed to have reached a point of agnosticism at this time.

Again, this is all so very well known in French Europe and Québec. Hergé the young man was a product of his times; he freely admitted his prejudices later on. He evolved, just as many baseball players did after Jackie Robinson broke the colour barrier.

Well, you seem to agree with me, then! Thank you for confirming that my articles were accurate.