Frans Masereel’s Route des hommes (men’s path)

In my humble opinion the best Belgian comics artist is not Hergé… The best Belgian comics artist is Frans Masereel…

I vaguely remember mentioning this to a couple of Masereel’s fellow countrymen and I’ve got two different answers (I must add that, in my view, of course, I chose my collocutors well): (1) a nod of approval; (2) something like: In Belgium we don’t view Frans Masereel as a comics artist.

(Needless to say that, besides some puzzled expressions asking “who are those?,” most of my possible Belgian interlocutors would react in a third way calling me a lunatic, or worse, depending on the person’s degree of Tintinophily.)

The first reaction was understandable because said person is an artist himself and what he does is akin to Masereeel’s work. The latter one is more interesting to me at this particular moment because it permits me to enter one of the muddiest territories in comics scholarship once again (when will I learn, right?…), the old conundrum: what is a comic?…

I’m not going to answer that question because it can’t be done. All the answers that one can come up with are rigged because they depend on a previous particular view of what’s essential in a comic (and that’s not only prescriptive, that’s also arbitrary). To Bill Blackbeard, for instance, speech balloons and image sequences are essential so (even if there are older examples, namely, here or even, here) comics started with Richard Felton Outcault’s Yellow Kid in 1896.

Saying this though, doesn’t get us very far (my thoughts on the subject, are here, by the way). What interests me right now are two related points: (1) the sociological side of the problem; (2) anachronism. (1) Words have a (social) commonly agreed meaning. The dictionary tries to stabilize it, but significations aren’t fixed. There’s a reason why we call Maus a “comic.” The sense evolved to include serious work while the signifier stood still. Even so I accept that “comics,” to most people, don’t include Frans Masereel’s oeuvre. Perhaps it will, someday… (2) Frans Masereel didn’t view himself as a comics artist. As far as he was concerned he did wood engravings, that’s all… To call his cycles “comics” is an anachronism. Maybe so, but it seems to me that we are guilty of anachronism all the time and nobody cares. To go back to Tintin, the expression “bande dessinée” didn’t exist when Hergé started doing comics. Why do we continue to say that he did comics, then?… Did the Lascaux painters call what they did “painting?” Is that important? How logocentric can we get?…

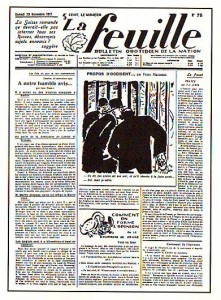

As you can see in this 1915 illustration above Frans Masereel was a naturalist. But working for the pacifist newspaper La feuille in Geneva as a political cartoonist during WWI Masereel needed a less detailed, more urgent, style. As Josef Herman put it:

Working for La Feuille posed two main problems for [Masereel], both of a technical nature. One was that the drawing had to be done quickly, leaving no time for the careful, detailed draughtsmanship he had practised until then. The other was how to achieve maximum effect using poor quality paper, on which thin lines were simply lost. He solved these two problems with the true instinct of a man of genius. He avoided drawing with a fine pen and took a thick brush, in the process giving up the search for tonal texture. He now used large planes of intense black, drawing lines wherever needed with a brush. The emotional effect he achieved was staggering.

Maybe the times weren’t right for nuanced views of the world (?). I love Frans Masereel’s verve and variety (he did manga in the original sense of roaming drawings), but his ideological views and Expressionist style push him into a less than complex view of the world sometimes (the fat, jeweled, cigar-chomping capitalist, for instance, is a regrettable stereotype). You can see one of Frans Masereel’s political cartoons as published in La feuille below:

Frans Masereel was 75 years old when he published Route des hommes (1964). He did “novels without words” all his life (more than 50, according to David Beronä). Route des hommes is far from being one of his best (that would be Passionate Journey – 1918 – and, my personal favorite, The City – 1925).

Route des hommes is about the horrible and great things that happen to humankind. We find in the book Masereel’s usual topics: war, famine, exploitation, but also progress, team work, joy, etc…

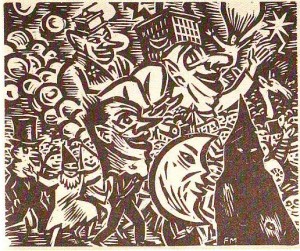

The greatest thing about this edition of the Musée des Arts Contemporains au Grand-Hornu and La Lettre volée (2006) is that it shows both Masereel’s prep drawings and his wood engravings. In this way we have access to the artist’s creative process as never before.

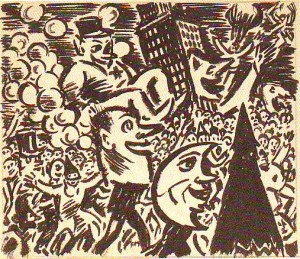

We can see above how Frans Masereel cites another Belgian painter, James Ensor (ditto Jacques Callot at some point). It’s interesting how what seems to be a tree in the foreground of the drawing becomes a sinister figure in the wood engraving (death waits us all at the end). His composition changes (increasing the two background figures’ size) greatly improve his work.

Masereel used allegory a lot. In this drawing the cars represent careless rich people. The city lights aren’t just that, they connote poor people’s acceptance of the status quo: they’re hypnotized, alienated (as Marxists liked to say)…

…But, to tell you the truth, I prefer allegoryless Masereel. He could be very poetic, as we can see above…

While I certainly have no problem with you or anyone identifying him as a cartoonist “avant la lettre”, it’s worth mentioning that in Thomas Mann’s introduction to “Passionate Journey” he identifies Masereel as a filmmaker which seems just as valid.

Here’s a couple of quotation:

“Recently a film magazine published abroad asked me if I thought that something artistically creative could come out of the cinema. I answered: ‘Indeed I do’! Then I was asked which movie, of all I had seen, had stirred me most. I replied: Masereel’s Passionate Journey.”

[…]

“As a matter of fact, Masereel is very fond of the cinema and has even written a scenario himself. He calls his books ‘romans en images’ – novels in pictures. Is that not an accurate description of motion pictures?”

Hi Daniel:

Here we are, after all these years (back then, the twenties?, no one but Gilbert Seldes thought that anything worthy of note came out of the comics industry), and I can imagine someone asking the same thing substituting “cinema” for “comics.” What’s funny is that the answer could very well be the same.

Actually Thomas Mann didn’t think that Frans Masereel did films. Here’s how your first quote goes on: “That may seem an evasive answer, since it is not a case of of art conquering the cinema but of cinema influencing art. At any rate, it involves a meeting and fusing of two arts – the infusion of the aristocratic spirit of art into the democratic spirit of the cinema.”

Thomas Mann knew that Frans Masereel was a graphic artist. He just underlined a democratic influence in his work and attributed it to Masereel’s love of cinema, perhaps… Maybe he was right, but I think that he was mostly wrong. Frans Masereel arrived to the novel in pictures (sounds familiar?) because he saw Medieval and Renaissance books with narrative sequences (the Dance of Death influenced him enough to do one of his own during WWII). Notice how there’s almost no montage in his books, no close-ups or medium shots (I can’t detect much of an influence from films). The democratic aim, that surely existed in him, can be traced to Expressionist Dresden group Die Brücke. Again, I’m not saying that Thomas Mann was totally wrong (I’m not sure about my last claim either), it’s just that I detect other, bigger influences.

Domingos, do you have any interest in/affection for Art Young? I guess the stereotypical capitalists just made me think of him….

Hi Noah:

Art Young didn’t cross my reading paths in a while, but I like his work (I never read his hell book though). Thanks for remind me of him.

Domingoes wrote:

“Here we are, after all these years (back then,

the twenties?, no one but Gilbert Seldes thought that anything worthy of note came out of the comics industry), and I can imagine someone asking the same thing substituting “cinema” for “comics.” What’s funny is that the answer could very well be the same.”

Yes, the eternal question: is x art, where x = a new and popular form of expression. In the twenties, this question was being asked about films. In the 19th century it was asked about novels. In the last few decades this question has been posed with regard to comics and more recently, video games.

Regarding your other points:

The lack of montage (as it is generally understood) in Masereel may have more to do with the fact that in 1918, when “Passionate Journey” came out in 1919 when (perhaps) the art of montage in movie-making wasn’t as fully developed. Eisenstein is generally credited with refining the technique and he didn’t seriously start making movies until the twenties I believe though I’m sure that a more diligent film buff could say more.

I would also argue that other Masereel picture novels do rely on a kind of montage. One of the reasons I prefer Passionate Journey over The City is that the latter seems more like a series of unrelated images; indeed, a kind of montage, whereas the individual illustrations in Passionate Journey seem more obviously sequential.

I can’t speak to the lack of close-ups, but it’s hard for me to look at some of the sequences in Passionate Journey and not see them as scenes in a movie, e.g. the opening sequence with our hero arriving on a train in the big city. The other influences you cite (Dance of Death et al) are significant and shouldn’t be dismissed, but my gut feeling is that the influence of movies was every bit as much (if not more) of an influence.

It’s interesting to note that Mann’s introduction was written in 1926, 7 years after Passionate Journey first appeared and with film technique in thos years, film techniques evolved rapidly. I’d have to line up Masereel’s novels up chronologically (including the many out-of-print ones that I’ve never even seen) to see if his own technique evolved accordingly.

I’ve mentioned this elsewhere…but one of the things that I think often isn’t sufficiently taken into account in discussion of “what is comics” is that mediums are as much, or more, historical than they are formal. What a comic is depends a lot on what people who make comics decide is an influence. Tintin has obviously had a huge influence on comics creators; it would be crazy not to consider it a comic. I don’t know enough about Masereel to make a judgment…but the fact that there’s this kind of debate around him suggests perhaps that he’s on the border between various traditions.

What this means in part is that artists or critics can turn something into a comic by claiming it strongly or successfully enough. Andrei Molotiu is trying to do something like that with Abstract Comics; that is, take a lot of things that wouldn’t necessarily have been seen as comics and bring them into the medium through assertion/curatorial effort. Will he be successful? Well, check back in ten years and see if abstract comics are less controversial then than they are now….

Gah, I wish I could edit my posts. Here’s a better version of one of the sentences above:

The lack of montage (as it is generally understood) in Masereel may have more to do with the fact that in 1919, when “Passionate Journey” came out, the art of montage in movie-making wasn’t as fully developed.

Daniel:

First of all I don’t disagree with you and Thomas Mann. Film influence was definitely there in Frans Masereel’s novels in pictures. But all the elements of what we may consider a film “language” was already present in Birth of a Nation by David W. Griffith (1915). I go even further back and claim that the true revolution can be seen in The Great Train Robbery by Edwin S. Porter (1903). If Masereel saw these films or not is another matter. Anyway, Route des hommes was published in 1964 and he still wasn’t using any close-ups and medium shots. Plus: I tried to read (here’s another good word for discussion when applied to purely visual signs) Passionate Journey as a film and let me tell you, Masereel’s montage is so jerky that Godard would be considered a Sokurov next to him.

Noah:

That’s my point exactly: it would be crazy not to call “comics” to Tintin’s stories (or Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant because it has no balloons). And yet, the modern equivalent to the English word “comics,” “bande dessinée,” was only used a few years after Tintin au pays des Soviets. What we call now “comics” was called at the time “illustrés” or “petits miquets” (little mickeys, after Mickey Mouse). I’m not sure if these expressions meant exactly the same thing, but I suppose that the answer is: no. I’m no linguist, but I bet that the expressions meant: children’s stories with illustrations.

By the way, if you are curious, the expression “bande dessinée” was a translation of the English “comic strip.” It was Paul Winkler who coined it at Opera Mundi Syndicate.

Pingback: Madinkbeard » Masereel’s Leaps in Time

Pingback: weekend review fumettologica -5 « Fumettologicamente

Pingback: weekend review fumettologica -8 « Fumettologicamente

Pingback: Was ist eigentlich eine Graphic Novel? Geschichte, Beispiele und Definition | Aicomic