The Criterion Collection DVD of Jean Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet contains a transcript of a lecture given by Cocteau in January of 1932 at the Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier, on the occasion of the film’s premiere there. Cocteau begins by talking about critics.

First of all, I will give you an example of praise and of reprimand that I received. Here is the praise. It comes from a woman who works for me. She asked me for tickets to the film, and I was foolish enough to fear her presence. I said to myself: “After she has seen the film, she won’t want to work for me.” But this is how she thanked me: “I saw your film. It’s an hour spent in another world.” That’s good praise, isn’t it?

And now the reprimand, from an American critic. He reproaches me for using film as a sacred and lasting medium, like a painting or a book. He does not believe that filmmaking is an inferior art, but he believes, and quite rightly, that a reel goes quickly, that the public are looking above all for relaxation, that film is fragile and that it is pretentious to express the power of one’s soul by such ephemeral and delicate means, that Charlie Chaplin’s or Buster Keaton’s first films can only be seen on very rare and badly spoiled prints. I add that the cinema is making daily progress and that eventually films that we consider marvelous today will soon be forgotten because of new dimensions and color. This is true. But for four weeks this film has been shown to audiences who have been so attentive, so eager, and so warm, that I wonder after all if there is not an anonymous public who are looking for more than relaxation in the cinema. (This is followed by several hundred words about the film, demonstrating that it is more than relaxation. )

Contrast Cocteau’s response with Chris Ware’s letter about the issue of Imp devoted to his work (published in the subsequent issue).

You’ve done what most critics, I think, find the most difficult – writing about something you don’t seem to hate, which, to me, is the only useful service that “writing about writing” can perform. You write from the vista of someone who knows what art is “for” – that it’s not a means of “expressing ideas,” or explicating “theories,” but a way of creating a life or a sympathetic world for the mind to go to, however stupid that sounds. Fortunately you’re too good a writer to be a critic; in other words, you seem to have a real sense of what it is to be alive and desperate (one and the same, I think.)

Both reactions are, at root, comparisons of praise with reprimand. Yet, unlike Ware, Cocteau apparently finds the reprimand more interesting than the praise. It is noteworthy that the praise Cocteau receives from his female colleague – and mostly dismisses as a kind compliment – is virtually identical to Ware’s stated purpose for art. It is even more noteworthy that Ware’s ideal is so limited in scope that it is entirely inadequate to describe Cocteau’s proto-Surrealist film, which he indicated was created as “a vehicle for poetry – whether it is used as such or not.”

Of course, perhaps Ware was only trying to be nice to the guy who devoted a whole issue of a magazine to him. There is something a little over-the-top about his phrasing. I try to give him the benefit of the doubt even though that letter put such a bad taste in my mouth that I think of it every single time I see the name ‘Chris Ware,’ and it casts a shadow over my appreciation of his work. I’m almost convinced that deep down he actually does agree with himself – is it possible that he really is actually as insecure as his self-presentation? – but I’m willing to be dissuaded.

As published, though, Ware’s letter voices incredibly facile positions on the purpose and value of criticism and art, stating (in opposition not only to Cocteau but even to Gerry Alanguilan) that “writing about writing” can serve no useful purpose other than to praise. (He at least has the sense not to use the word “criticism” in this context.) The letter implies not only that Ware feels he has nothing to learn from critique but that critics who dissent with the Vision of the Artist are somehow bad, not “good writers,” dry and dessicated and less-than alive. This is an evisceration of the existence of criticism, exiling “writing about writing” to the commodity function of marketing and “Comics Appreciation 101” for books that reviewers like.

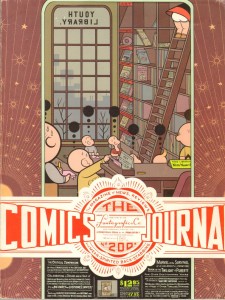

Unfortunately, Ware’s cover for TCJ 200, which also touches on this theme, only gives a little evidence in his defense: his library shelf appears to be a stack ranking of comics “genres,” with pornography and criticism at the bottom, and Art at the top – but nothing on the shelf.

The page is at least slightly ambiguous: there’s really nothing that mandates the shelf be read as a hierarchy rather than a pyramid with criticism and pornography as comics’ foundational pillars. It’s a very open depiction with both interpretations in play. Against the letter’s statement that art is not for “expressing ideas,” the cover expresses plenty of ideas: the juxtaposition of the “youth library” with a setting that is obviously adult (the high ladder, the call slips for closed stacks, the pornography); the ambiguous hierarchy/pyramid itself; the absence of anything much on the “art” shelf; the blurring of age – the cartoon characters depicted are all small children, but they’re behaving like adolescent boys, filling out call slips so Nancy will climb the ladder and they can see up her skirt –; and the resultant indictment of comics fandom and subject matter as stunted and age-inappropriate juvenilia. (Irrelevant aside: the periods in the window and on all of the signs really bug me.)

Yet despite that pretty interesting cluster of ideas, the blunt, indiscriminately ironic tone undermines them by flattening any possible value distinctions. That works strongly against any optimistic interpretation of Ware’s point. Gary Groth in the psychiatric help box is the most honest bit of the page, which verges past Ware’s routine self-deprecation into a scathing self-loathing that reaches beyond the individual to the group. This Ware would only join a club that would have him as a member so he could mock them for their bad taste. It is only funny if one has infinite patience with self-awareness as an excuse. Unless one gives Ware the benefit of the doubt to start with, this panel exudes little more than anger and contempt.

So is the letter too just another example of Ware’s incessant clanging self-deprecation? “My art expresses ideas, so it doesn’t quite measure up to the best purpose of art”? I don’t really think that’s the case.

Ideas take many forms, including images and certainly there’s nothing wrong with expression. The use of art by individuals to express themselves is of time-tested value. Ware’s letter elides the fact that his stated purpose, the “creation of a life or a sympathetic world for the mind to go to,” involves almost exclusively the expression of ideas about that life/world, despite his rejection of ideas as fair game. The letter’s point, though, is prioritizing the evocative experience of a visual “place” over the cerebral experience of ideas or theories, and Ware is far better at evocation than he is at ideas and theories.

So I think his art is consistent with his theory of art in the letter. Despite the frequent self-deprecation, he doesn’t really need praise artistically. He is perfectly well aware of what he does well. He rarely sets himself artistic tasks he cannot execute flawlessly.

More often than not, complexity in Ware’s drawing derives from the intricate realization and juxtaposition of ideas on his carefully crafted pages rather than from a complex interplay among the ideas themselves that is then, subsequently, represented on the page in an equally complex way. The repetitiveness of his aesthetic and the relentlessness of his irony further limit the range of conceptual material available to a critic. Although it’s possible to interpret the TCJ cover as ambivalent about criticism, the hint of ambiguity is just that – a hint. Ware does not tackle the layered ways in which the ideas interact. The concepts consequently never mature into a meaningful new insight: the piece is a meaningful representation of very familiar old insights. Overall the cover is smart, but not much more substantive conceptually than the best editorial cartoons. Unfortunately, this is often true for Ware’s other work as well.

Ware’s rejection of “ideas” and “theory” thus feels tactical, veiling the extent to which his art is not well served by analytic criticism, even of the most explicatory ilk. Ideas in Ware’s art lose a great deal when they are articulated. Spelled out in prose, without the grace of his talent for imagery, they lose their “life” and become bland. Since one of criticism’s essential actions is to articulate the interplay of ideas and hold it up to scrutiny, Ware’s work cannot consistently stand up against criticism that does not appreciate it. At the very least the analysis must appreciate his psychological angle – the particular voicing of interior life against exterior pressures that counts as story in much of his work. Praise that “gets” him can serve as explication for less savvy readers, but criticism that rejects him deflates his project entirely.

In the counterexample, Cocteau explained his film by embracing the very transience that had been leveled against him as a criticism. This was axiomatic for Cocteau: “listen carefully to criticisms made of your work,” he advised artists. “Note just what it is about your work that critics don’t like – then cultivate it. That’s the only part of your work that’s individual and worth keeping.” Even his stance toward criticism itself stands up to the scrutiny of articulation, as he was surely only half-serious: he wrote criticism himself, he counted among his friends the art critics Andre Salmon and Henri-Pierre Roche, and he was acquainted with Apollinaire (who, alongside Sam Delany, Salman Rushdie and Joan Didion, illuminates why Ware’s phrase “too good a writer to be a critic” is mere ignorance).

Ware’s letter, with its casually passive-aggressive muzzling of critique, is the very opposite of “listening carefully”: it’s a kinder, gentler playground bullying of the class brain. Cocteau’s contrasting approach, rich with confidence, recognizes how the relationship of artist and critic can be that of interlocutors. The conversation may happen in writing and the artist and critic may never actually speak to each other face to face, but criticism as such is inherently fecund. Critics model ways of talking back to art, and talking back increases and vitalizes the relationships among any given art object, the people who engage with it, and the culture in which it operates. It is precisely the thing that moves art beyond being merely the “expression” of an artist, toward a more ambitious function as a site for cultural engagement and debate. Critics and readers are also interlocutors; the critic is thus interfacial, and this triangulated conversation in many ways demarcates the public sphere. Artists who reject this conversation show contempt for their readers. They are, in contrast to Ware’s assertion, far more interested in self-expression than in any other purpose for art.

What I find most disheartening is not this disingenuousness with regards to expression, not that Ware discourages writers from writing criticism (we are a hardy bunch), but that he encourages contempt of writers who do write criticism and contempt of the modes of thought modeled by criticism by any readers and artists who pay attention to the opinions of Chris Ware. Regardless of his motives, Ware’s letter throws his not-inconsiderable weight behind an approach to art – and of engagement with art – that invalidates and forecloses thoughtful, cerebral engagement.

This kind of careless anti-intellectualism is not a philosophy of criticism. It shuts down several questions that are utterly essential for comics criticism: whether the existing critical toolkit, with its heavy emphasis on prose explication of illustrative examples, is in any way sufficient to capture the native complexity of comics, whether viable alternatives exist, and to what extent and in what ways it matters that translation to prose evacuates the complexity of many comics texts. (The fact that explication of Clowes’s work does not evacuate his complexity is an important argument against the knee-jerk assertion that complexity in comics is somehow entirely different in kind from that found in literature and film, but the point is surely open to debate.)

Criticism is the correct place to argue the merits of different ways of making conceptual meaning in comics, and that conversation is not really possible in “writing about writing” that attempts nothing beyond praise. But that conversation is absolutely necessary if comics are ever to respond to the challenge Seth articulated in Jeet Heer’s panel: “I guess it is a failing of the culture not to have recognized anything in comics, but it’s also a failing in comics, to have not presented much for them to recognize.”

I said in the beginning of this essay that Ware does not understand what criticism is for, and his cover art, in its typical bleakness and self-deprecation, dramatizes this limitation of his imagination. Criticism is the thing you need before you can have something on Ware’s top shelf, the one labeled Art. The one that, for Ware, is unsurprisingly empty.

Update by Noah: Matthias Wivel has a thoughtful response here. Also, the thread here was getting unwieldy and has been closed out; if you’d like to respond please do so over on the other thread.

Holy god that’s a great essay.

I need to think some about whether I think that Ware’s ideas really do always lose in the explication. I think he has been capable of fairly subtle thoughts at some points in his career, at least…and, for example, I think that there is lots of material in his work around masculinity and father/son anxieties that a critic could talk about (I don’t know that Ware would really like where those discussions go, but that’s a little different than the criticism of his work you’re making, maybe….)

I don’t know. You base a fairly strong critique of Ware’s work on two rather marginal utterances, a short, admittedly facile letter, and his Comics Journal cover, whose irony you downplay.

It seems a little insufficient for a guy who has thought, written and said so much — much of which can be called ‘criticism’ — about comics, and who clearly respects it as an endeavour.

Your argument against his myopic Imp letter is a well taken — many artists periodically make these kinds of statements against criticism, presumably because they dislike bad things said about their work, and it is indeed an ignorant stance, but to suggest that it says anything about profound deficiencies in Ware’s work as such is hard to accept, in that it rests on an uncharacteristically shallow comment rather than analysis of the work itself.

Fascinating piece about Ware’s art. His ideas on criticism itself are half-formed (at least in print) and less worth listening to. However, he does practice what he preaches in various comic introductions.

I think the TCJ #200 cover is reasonably complex and multi-layered in the way it presents its ideas. A comment on the expectations of the marketplace, the nature of its readers or the base roots of comics (as represented by Barnaby, Charlie Brown, Jimmy Corrigan, Leviathan, The Yellow Kid, Tintin etc.) themselves? And the topshelf labelled “Art” isn’t empty at all since it’s filled with Nancy B.’s butt. Couldn’t this be seen as a kind of snide commentary on the nature of “Art”? In my eyes, it’s significantly better in terms of the interplay of ideas than most of the editorial cartoons I’ve read/seen.

But maybe I’m getting your position all wrong. What comics cover best expresses the “ideal” you’re looking for?

“This Ware would only join a club that would have him as a member so he could mock them for their bad taste.”

That’s a good line. Two thoughts:

1. I’m not sure the quotation from Cocteau is any more defensible than the one from Ware. He picks a critic’s opinion that’s self-contradictory, i.e., one who “does not believe that filmmaking is an inferior art,” yet “reproaches [Cocteau] for using film as a sacred and lasting medium, like a painting or a book.” That’s an easy target, so that Cocteau can basically pander to his audience: “for four weeks this film has been shown to audiences who have been so attentive, so eager, and so warm, that I wonder after all if there is not an anonymous public who are looking for more than relaxation in the cinema.” That is, the artist becomes a defender of the public’s intelligence against the critic who believes them “looking above all for relaxation, that film is fragile and that it is pretentious to express the power of one’s soul by such ephemeral and delicate means.” This isn’t all that different from a Michael Bay who’s only concerned with entertaining the crowd. Cocteau’s saying who needs critics, the important relation is between his art and his target audience.

2. I don’t how much stock I’d put into a cover Ware did for a magazine of comics criticism. It seems just as likely that he was having a bit of fun at Groth’s expense.

Matthias: I don’t think I downplay the irony in the cover. It is saturated with irony, I agree. What I say about it is that the irony is so unrelenting that it undermines the potential for sophisticated conceptual meaning. I don’t think irony for its own sake counts as an idea. Ware is so unrelentingly ironic and bleak — throughout his work — that I think that actively takes away from his conceptual complexity.

My experience is definitely not comprehensive, but I do feel that Ware’s other work is largely subject to this same critique to varying degrees. He is far more masterful with visual than conceptual material in all his work: the cover is just a concise example that can be covered thoroughly in a blog post.

I would absolutely love to see each point argued against any and all specific texts, especially with counterexamples from artists who have a different vantage point toward the value of cerebral engagement. Ware receives a great deal of critical praise, yet even at his best he does not pack as big of a conceptual punch as equivalently praised artists from literature or fine art or film (Cocteau? Rushdie? Jeff Wall?) or even, really, in comparison with a cartoonist like Clowes.

Those artists are all more open to considering critical ideas (and, with the possible exception of Clowes) write criticism themselves. The Cocteau comparison is meant to underscore how much he utilized criticism as a mental and artistic challenge and a source of inspiration.

Given that so many significant artists make so much hay out of a less hostile attitude toward ideas, I would therefore definitely consider Ware’s stated attitude toward criticism a “profound deficiency” — but in his approach to art. Tracking how particular aspects of approach manifest themselves throughout an artist’s ouevre is much too complex for a 2500 word blog post. I completely agree with you that evaluating that on a case-by-case basis is absolutely required, and I’m eager for you to explicate for me the example of Ware’s work that overcomes this opinion and makes him equal with Rushdie in my mind. (Noah successfully made me respect Clowes on this very issue, even despite himself, so I really can be dissuaded!)

And thanks, Noah, for the praise. I’m glad you enjoyed it. :-)

The snide sneer at art, whether empty shelf or Nancy’s butt, still plugs (as it were) into the defensive anti-intellectualism that Caro is talking about, though, doesn’t it?

Ware’s self-loathing/self-pitying take on the position of comics (as adolescent literature, as too difficult to produce, as emotionally stunted, etc. etc.) is a fairly consistent theme in his work. It is ironized in some sense, but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t take it seriously too, as Caro notes.

I see where Matthias is coming from; Caro isn’t looking at everything Ware has done, and there is obviously a lot of it. On the other hand…I think Ware’s very self-conscious defensiveness is a thread throughout his work. I don’t think it’s out of bounds to ding him for it.

Suat, have you seen any Zen ink drawings? I was just looking at a couple in the Smart Museum here in Hyde Park; one in particular called “Zen Puppy,” which was riffing on the “does a dog have Buddha nature?” koan. I was thinking about how they compare to editorial cartoons; there’s text, there’s art, there’s even kind of a joke, but it’s handled much more elliptically — more like a poem than a prose sermon….. They’re just incredibly beautiful and funny at the same time. I would love to see that sort of thing taken up as more of an influence by comics artists, though it doesn’t seem very likely anytime soon….

Jeff Wall is a great example too, of someone who is extremely ironic (even bitchy), but whose irony is a lot less flat, and seems to open up possibilities rather than closing them down as Ware’s often seems to.

Some of Ware’s earlier work was more directly satirical, and very funny. I think that was more successful in many ways; it sort of harnessed his bitterness to his ideas a la Swift rather than putting them at cross-purposes to each other.

And Charles, don’t know why your comment didn’t show up at first…but that’s a pretty great take on the Cocteau quote.

I bet the pornography and criticism being in the same slot is Ware teasing Groth about Eros….

Charles: Yes indeed, Cocteau had a very performative relationship with critics. I think he absolutely manipulated that quote for effect. And if you look at the later quote, toward the end of the essay, that twisting of criticism to suit his own ends is very clear. He’s just immensely confident: he takes what he wants, twists it to what he wants it to be, and leaves the rest.

I think it’s more defensible than the Ware because it is so confident — so CREATIVE. He creates something from the criticism he receives, he assimilates it into his imagination, and it makes his understanding of the world and art and readers and critics richer. In contrast, Ware just tries to shut it down, like a middlebrow mom, “if you can’t say anything nice you shouldn’t say anything at all.”

Suat: Noah said a lot of what I was trying to work in. I agree with you that the panel is “reasonably” complex and multi-layered. But it’s not “tremendously” complex and multi-layered. It depends on what you compare it to. And in most other art forms, the artists who get the degree of critical adoration that Ware gets are a lot more complex and have a much more sophisticated relationship to “ideas” and conversations about ideas, and criticism, than Ware does.

I seriously would be over the moon if someone would send me a quote where Ware contradicts what he said in that letter, or even where he talks about criticism and art in a different, more open-minded, more ambitious way.

And I’d love for someone to point out a piece that would lose nothing by articulation in prose. I don’t love Ware and I haven’t read and reread everything, but I have read enough to know that I have this reaction consistently to most of his work, so I would be thrilled to find something that presents a really original, powerful, brain-changing take on his familiar constellation of themes.

I think about the extended abstract conceits that appear in Cocteau’s work — in Blood, it’s these layers of references to history, to classical narrative and theatrical convention, knit together with psychology of perception and surrealist philosophy (which Cocteau’s film then recursively helped expand), to create a new understanding of what poetry could be and, more importantly, how meaning consistent with the surrealist vision of poetry could be represented in film.

Telling someone in words what that film is about creates an intellectual experience just as sophisticated and complex as watching the film, if not more. It’s aesthetically very different, but Cocteau’s concepts are smart enough and original enough and subtle enough that they aren’t diminished when you talk about them, and the film continues as you talk about them to influence and enhance your understanding of the concepts. The film encapsulates its meaning in a more powerful way than description of it can, but the meaning is something in addition to its representation that can be transported into other forms.

Ware is all about the form. There’s nothing much uniquely WARE left when you remove the drawing. And I think that’s because he’s too busy insisting that drawing is a way to think to value any other way of thinking at all.

Noah, you say:

“Some of Ware’s earlier work was more directly satirical, and very funny. I think that was more successful in many ways; it sort of harnessed his bitterness to his ideas a la Swift rather than putting them at cross-purposes to each other.”

Can you think of a specific example? I’ll try to get ahold of a copy and check it out…

I was with Noah right up to where he called Chris Ware a mom. Mama’s boy possibly, which I can relate to, but a nurturing peacemaker? I doubt that.

I was thinking about the artistic force of “ressentiment”– Nietzsche’s term for existential sour grapes. The essential feaure of “Comic Book Guy” on the Simpsons (do you all think about him ever?).

I’m certainly not the first to notice that Nietzsche’s syphilis-addled Wagnerian ravings have a touch of that very quality. As does all male fear of castration, or of homosexuality, or of intimacy, or of everything, What other creative drive is there? For men, anyway.

In a sense, criticism is the ultimate male art form. Which does nothing to obstruct women from writing good criticism, but rather gives them a slightly chilling degree of objectivity.

Lots of the ads in the early Acme issues; I always think of his ads for “Negro Storage Boxes,” referring to the high-rise projects — I can see Swift chuckling at that.

His earlier stuff also tended to take detours into the sureal with more frequency…I don’t know. There was sometimes a sense of wonder that was at odds with his bleaker, more pedestrian stuff. There’s a little of that in the sci-fi sequences in Rusty Brown too, I think, from what I’ve seen of them.

I sometimes feel like his more poetic instincts are fighting a war against his consciously articulated belief that comics should be really boring if they’re going to be sufficiently serious and worthwhile.

“He rarely sets himself artistic tasks he cannot execute flawlessly.”

I think that’s a painful hit. Ware’s incredibly ambitious…but only in certain areas. He’s not willing to make a mess of things, which I think is a real limitation as an artist.

OH– funny early Ware. Anyone remember “Large Negro Storage Boxes” as an ad for prisons? Or the thoroughly morbid Big Tex comics? Or the totally batshit crazy and gorgeous Quimby the Mouse stuff?

Yeah, he fell off in a big way.

But don’t let that stop you from discussing my “ressentiment” idea.

Caro called Ware a Mom, not me.

It was an ad for prisons! That’s better, actually — I had forgotten that….

In the same issue as the storage boxes there was something for Indian reservations too.

Chris Ware succumbed to the lure of the poignant. Poignancy is such a sad, exploitive, overdetermined excuse for almost any other less fabricated emotional response. It’s what usually helps NPR hit me right in the gag reflex.

Caroline,

I see two competing impulses in this essay: one wanting to go behind the curtain and understand the artist’s impulses and attitudes toward art in general and criticism, and one trying to connect that to the art itself.

Let me make a suggestion: if you’re really interested in the former (especially regarding the artist’s frame of mind) and how it relates to the latter, I would strongly recommend reading the two Acme Novelty Datebooks. These are his sketchbooks, and reveal quite a bit about the artist.

I did call him a mom, but not a good nurturing mom! Like an annoying ’60s sitcom mom who won’t let her kids play baseball or who gets mad when you get peanutbutter and jelly on your nose. Like the manners police of comics criticism. “Be nice, don’t curse, can’t you find something good to say, blah blah blah.” How boooring.

Criticism is a mighty fine way out of the slough of poignancy.

I will hunt down the prisons thing. One thing that came close to making me reconsider this opinion was a Quinby the Mouse piece, the “I’m a very generous person” breakup thing, but in the end it’s originality just didn’t quite measure up enough to make it ok for him to exhibit the kind of arrogance and ignorance that’s just overflowing from that letter. And all my impulses in that direction were killed off by that recent Halloween New Yorker piece, not the cover but the inside story, whose narrative and concept were so palpably lame and tired that it made me completely unwilling to give him any benefit of the doubt.

I did read Acme 19 very recently too (I think it came up here when were were talking about that New Yorker) and I had exactly the same experience with that as well. It’s beautifully rendered, the images have texture and resonance and they make allusion to a large vocabulary from several historical periods — and the story is extremely familiar and tired, the concepts are blunt and mostly psycho-experiential, the tone sags to the point it has more in common with contemporary poetry than the science fiction its riffing on, and the allusions add very few original insights to their source material.

This is probably calculated: I gather that he feels the world will be more compelling, more “sympathetic”, if it is recognizable. The problem is, he isn’t deft enough as a writer to maintain that recognizability, that resonance with the things you know, while still adding in original narrative, thematic, and conceptual material. He puts all that in the art and thinks it’s good enough.

My personal reaction to Chris Ware’s work has been to run in the other direction as quickly as I could.

It’s not that I don’t respect him. There aren’t too many modern comics creators who are advanced enough as artists to contend with what Harold Bloom describes as the “anxiety of influence.” For those not familiar with lit-theory, it essentially means that an accomplished creator produces their best work in competition with a predecessor. He or she competes with that predecessor by beating them at their own game in a way that takes the predecessor’s ideas in a radically different direction. Alan Moore, for example, has produced his most notable work in an “anxiety of influence” mode relative to Harvey Kurtzman’s efforts in MAD and the war comics.

Ware’s anxiety of influence figure is Charles Schulz. And the way he competes with him is frightening. It’s like watching a Hemingway follower compete with his idol by merging the terse, absence-of-a-presence sentence style with the expansive expository approach of Proust or late-period Henry James.

Ware’s overall approach is that of someone who may be too smart for his own good, and who seems determined to prove he’s smarter than everyone else. (Hey, if you can beat Schulz, who can’t you beat.) His problem with critics is that he might be afraid they’re smarter than him. And if they can effectively explicate him, he’s probably right, even though being smarter than everyone doesn’t necessarily make one’s contributions to the arts superior.

Hey Rob — thanks for the recommendation; I’m texting the house librarian now to find out what shelf they’re on. :-) (I’ve read a bunch of the other Acme stuff but I don’t think I’ve read the datebooks.)

To answer your question about what I’m interested in: mostly in the Imp quote as such, the damage it does and just how bad it is as a statement for what Art and criticism should be, more than as a “clue” to the rest of Ware’s work. Chris Ware is so critically lauded that I think it matters that he said this, even if the rest of his work completely contradicted it (which I don’t think it does).

I definitely hope it will turn out that he is much more critically minded than he appears to be, but I don’t think that even if he wrote into TCJ and said “I take it back! I didn’t mean what I wrote to Imp! I’m sorry!” that I would change my mind about the limitations of his work. I’m just not that impressed by his writing — I am impressed by his drawing, just not his writing — or by the way he talks about art in the interviews and things I’ve read.

I went back and read all his comments in Jeet’s posts from earlier this week, just because that was a proximate example, and one of the things that really stood out was the bit about how he wanted his teachers to read what he’d put on the page and they were only interested in the composition: I think he must have learned a great deal more about composition than he did about writing. His storylines and characterizations are just not mature, fully formed art in their own right.

Now, what he says is smart enough, and it’s well articulated, and it’s perfectly clear that he’s careful and engaged — but there’s absolutely nothing there that hasn’t been said before and nothing that’s particularly complicated or subtle. He is far more interested in psychological effects, tinged with irony, than he is in conceptual depth. Unfortunately, though he’s not a person with tremendous native insight into psychology; it’s very hard for him.

I’ve often thought that people get extremely interested in things that are just a little too hard for them, mostly in their grasp, but still challenging enough that they take work and that it’s exciting to figure something out. I think psychology is that for Ware, and it means his work is facile to anybody who has a deeper intuition about psychology than he does. I think his attitude toward criticism is one of the reasons he hasn’t been able to recognize that and move beyond it but instead is getting sucked deeper into it.

Perhaps because art comics have been so dominated by autobiography for so long it’s hard to recognize the limitations of the autobiographical perspective. It’s not that there are no great autobiographies, or that a great artist can’t write a great autobiography, but the best artists are not fascinated by demarcating the parameters of their own limitations like Baudrillard’s map – they are too busy leaping off cliffs to see what shape they’re in when they land. Noah got it just right: Chris Ware is just too afraid to make a mess.

And…I agree with everything Robert just said.

I’m not much of a fan of Harold Bloom (I think Terry Eagleton said of his anxiety of influence theory something like, “a brilliant theory, whose only flaw is that it is false.”) I don’t think Moore’s best work has been in a Kurtzman vein necessarily, for example. And, anyway, Moore just isn’t a very anxious writer in general. It’s difficult to see him as really too worried about what some father figure says about his work, to me at least.

Ware is someone who is so obsessed with fathers and anxiety that it’s hard not to see him at least in part in terms of Bloom’s formulation I guess — or at least, in terms of the Freudianism that influences both Bloom’s theory and Ware’s practice to some fairly significant extent.

Ware’s obviously very indebted to Schulz…though he’s at least as fascinated by Winsor McCay…and by literary fiction too.

Bert: on the ressentiment. I think that may be BRILLIANT! I’m still wrapping my brain around exactly how: there is such a moralistic quality to the Imp letter (that’s the mom thing!). Yet it’s a corrupt morality, one that defends against “improvement” and correction and maturation, rather than opening up some movement toward perfection. It’s almost exactly Nietzschean.

This could conceivably be Ware’s point, with all the bleakness and resentment. He could be this completely performative missionary for nihilism, never explicitly stating but always advancing it.

That’s really creepy.

It still doesn’t make him original, but it’s definitely much more interesting to think of his books as The Illustrated Geneology of Morals than to try and think of them as literature.

I’ve been called briliant! I can now finish my critic career, and get around to spear-hunting sharks.

“Passive aggressive” is pretty brilliant too, as a summary of Ware’s neurotic pathos (there were several good zingers actually). Both the auteurs and the hateurs (just made that up), the moralists and les immoralistes, suffer from the same problem– lack of humility.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but Charlie Brown’s (or Joseph K.’s) self-pity was endearing, but it was ridiculous. It certainly made him relatable, but, unlike Jimmy Corrigan, or the other orthogonal-crystal-matrix-inhabiting hallucinating Ware introverts, it didn’t make him deep. Depression is, by one’s own actions (volition is another issue), choking off your own sources of light, water, and air with the bulk of one’s own solipsism. It’s meaningful but it’s not noble.

I was looking back at Matthias’s comment that Ware has written and said “much that could be called ‘criticism'” and I want to make sure I’m not missing anything. Jeet brought this same thing up responding to me over at Comics Comics, actually.

What I have seen from Ware that could conceivably be called ‘criticism’ are interviews and introductions, primarily. (I’m considering the benefits of beer and a reread of McSweeney’s 13 on the back patio at the moment.)

What I am deeply curious about is whether Ware has written anything comparable to Jeff Wall’s extraordinary Frames of Reference, a piece that documents the artist’s engagement with both the “anxiety of influence” and the dominant critical reception of his work, all put to work in an attempt to re-situate himself conceptually. Does such a piece exist?

But Ware’s characters are supposed to be ridiculous too; Jimmy Corrigan lurches from one pratfall to another. He’s certainly not supposed to be noble; he’s despicable mostly. Same with Rusty Brown.

I agree that there’s a difference between Charlie Brown and Jimmy Corrigan, but I don’t know that that’s it….

Caro, Jeet would know if anyone would. Maybe he will appear and enlighten us if I chant his name?

Jeet! Jeet! Jeet!

We’ll see if that works….

Bert! Criticism should be excellent preparation for a career spear-hunting sharks.

I think I’m gonna put that line about the “bulk of one’s own solipsism” in my email sig.

Jeet! Jeet! Jeet!

He and Matthias can join forces in beating up on me. But I will block their deflating arrows with my really thick Collected Writings of Apollinaire!

I feel solipsistically touched by that. As far as I know.

Poignancy is really different from really being obviously your own worst enemy. We are not to laugh cruelly at Jimmy Corrigan missing the football for the thousandth time, and then find his degradation endearing. We are to feel superior to his detractors and ache for his cosmic plight. We too are owed something by this world that has only given us life and sustenance, and it needs to pay up.

I think you get at it when you say “we are to feel superior to his detractors.” I’m not sure that’s exactly the case — we’re pretty clearly supposed to feel superior to Jimmy Corrigan too. But the thing in Peanuts which is quite different from Jimmy Corrigan is the ensemble cast; it’s never just about Charlie Brown’s pain because Lucy is really as important a character as he is. As a result it never breaks down into the agonized male sadistic/masochistic, ogre father/crushed child dynamic that Ware tends to have going. Lucy isn’t the ogre father; she’s a bossy six-year old named Lucy.

I think some of Ware’s more recent stuff moves towards ensemble casting too, though…not really sure how that worked out, since I sort of got off the bus before that happened….

I think it’s about more than first-person versus ensemble casting. All first-person narratives are not insufferably navel-obsessed. I mentioned Kafka– his protagonists are ciphers, and Charlie Brown is too, but they are not deprived of an interior life.

Crappy sitcoms have ensemble casting, and cipher characters, and they’re still all about valorizing a petty topos of self-image.

Yeah, that’s a good point.

Maybe it is depression. Neither Kafka nor Schulz really feel depressed…same with someone like Beckett really. They’re all comedians, really. The futility of existence is mostly seen as a reason for humor, whereas in Ware the jokes tend to be there mostly to point out the futility of existence. There’s a difference in emphasis which doesn’t maybe seem like it should matter that much, but ends up being very important.

Or maybe it’s just what Caro kind of says; Ware has limitations as a writer. Schulz and Kafka are really inventive and weird, both verbally and narratively. Ware can be too sometimes…but sometimes not.

Caro: “And I’d love for someone to point out a piece that would lose nothing by articulation in prose. I don’t love Ware and I haven’t read and reread everything, but I have read enough to know that I have this reaction consistently to most of his work, so I would be thrilled to find something that presents a really original, powerful, brain-changing take on his familiar constellation of themes.

Ware is all about the form. There’s nothing much uniquely WARE left when you remove the drawing. And I think that’s because he’s too busy insisting that drawing is a way to think to value any other way of thinking at all.

I’m just not that impressed by his writing — I am impressed by his drawing, just not his writing…”

I think this is where the difference lies between those who like Ware and those who don’t. Almost everything about Ware (the language, the ideas etc.) is in the drawings and the formal properties of his stories. I just don’t see this as a flaw. He’s probably an essentialist at heart and would probably hate it if you could successfully recreate the feeling of one of his stories in prose.

What I find interesting about Ware is his manipulation of time and space on the comics page and his “anxiety of influence” in this (to use Robert’s term) is Richard Maguire’s “Here”. If there is a reason why Ware’s take on Schulz seems overly “expansive” and “expository” it would be because of the far greater influence (for better or worse) of Maguire. I’m less interested in Ware’s depressive ideas on “life” but these have undoubtedly managed to draw in a number of readers less interested in his ideas on comics.

I think something like Citizen Kane can be brought up in this respect. It’s not my favorite film and I find the characters and plot tepid in comparison to many a novel. The pleasure I find in it derives primarily from its formal properties and techniques, in how the simplest of stories can be told in “new” ways.

Bravo, Caro.

I’ll just add that the Storage Boxes are in the wraparound ads on issue #10. It’s the definitive Acme…

…which my brother handed back to me and said, “I only read the ads.”

ROTFL, Bill. Many thanks for identifying the source; we’re digging Acme 10 out now…

Suat — I’d be on board with what you’re saying if I thought Ware would be satisfied with being described as “the cartoonist who does interesting experiments with visual representation of time and space.” I agree that he does some pretty interesting stuff with that (that Quimby the Mouse cartoon I mentioned is an example, I think). But I certainly have the impression he is aiming to do much more than that, and most critics don’t limit their praise of him to such a narrow scope.

Like I said, Chris Ware’s relationship with criticism will be a bit clearer if you read the datebooks.

Honestly, I don’t really think it matters to criticism as a whole if Ware wrote a letter to the Imp. To me, it shouldn’t matter what artists think about criticism. Most artists will take take from critiques what they see as useful and discard the rest.

I even have some sympathy for the position that critics have a parasitic relationship with artists, that without art there is no criticism. I think it was Moliere who said that the artist is to the critic as the horse is to the horsefly. And it may amuse you to hear that a University of Florida comics symposium, Dan Clowes (the keynote speaker), opened his speech by saying, “I stand among you, a horse among horseflies…”

Of course, I don’t ascribe to this view; the artist is necessary for the critic, but it’s not a parasitic relationship. In fact, the relationship is not between artist and critic, it’s between critic and work of art.

Two other points: I agree with Suat that there is no splitting Ware the artist and Ware the writer: they are one and the same. He views comics as a separate language, creating a different formal experience. Whether or not that highly formalized and stylized kind of writing is appealing is up to you to decide.

Point two: my theory is that each subsequent book of Rusty Brown will focus in on one of the seven primary characters. Some of the upcoming characters will be very different from Jimmy Corrigan, Rusty Brown or even Woody Brown. I’ll be curious to see just how different they are, and how well Ware does in voicing a different character. Going back to Schulz, my suspicion is that they will all represent different aspects of his personality, in much the same way that each of the major characters in Peanuts represented different aspects of Schulz.

Suat, I should also say that I am absolutely positive that neither Cocteau nor, say, Rushdie, would be satisfied with or even happy about a prose summation or description of their work either. But the fact remains that if you summarize the conceit that governs Midnight’s Children, even just in one or two sentences, it’s fascinating and really really frighteningly smart and entirely original and EVEN THE SUMMARY can affect the way you understand Indian history after 1947, not to mention more generally the ways in which racial and religious prejudices work to diminish human freedom and potential. Rushdie transformed his personal experiences into something that deepens our understanding of almost every significant political issue that’s affected humankind in the 20th century. Can you make a claim on that scale for anything of Ware’s?

And yet Rushdie and Ware are fairly comparable in terms of the respect they garner from critics. If someone said “who’s the Salman Rushdie of comics?” people would either say “there isn’t one” or they’d say Chris Ware.

And it’s not like Rushdie doesn’t ALSO do formal experimentation comparable in scope to Ware’s with space and time — in fact, his particular use of magical realism allows him to experiment not only with the “anxiety of influence” of previous magical realists but even to experiment with space and time in ways that are quite similar to Ware’s.

Jeez, this is rough. I don’t have to like Rushdie just because I dislike Ware do I?

I don’t think it’s really right to say that Rushdie is as innovative formally as Ware is, or has been. I think in that way Ware is much more comparable to someone like Nabokov, who was also really interested in formal/conceptual puzzles and fitting pieces together, often in a way that could seem somewhat bloodless.

I think there’s a logocentric bias to both criticism and philosophy which makes it difficult to grapple with comics in some ways. But, with Caro, I think those difficulties are also problems endemic to comics. I think Suat and Rob are kind of wrong when they say that Ware thinks through images…or, in Suat’s case, that it is possible (at least for me) to bracket Ware’s fairly banal insights about “life” off from his formal achievement. Nabokov was able to integrate his ideas into his formal games, in part because both ideas and games were made out of language. Ware, on the other hand, is stuck running through his formal machinery a lot of fairly banal insights taken at second-hand from the kind of second-rate literature that Nabokov mercilessly mocked. It’s like the heavens parting and Zeus descending and opening his mouth and hearing him speak with the voice of Calvin Coolidge. It’s aesthetically unfortunate, and even a little disturbing.

There are some traditions that have figured out a way around this problem — Zen ink painting, for example, manages to combine expressiveness and allusiveness in a way that’s fully integrated and sublime, and I think fine art has also figured out some elliptical means of formally combining image and text and even elements of narrative. I don’t know that Western comics is really there though. I do know, though, that the effort to make comics art by shoving literary material into a visual bag leaves me almost entirely cold.

Rob — I definitely see a lot of self-criticism in the sketchbooks, and I see a great deal of historical and environmental observation and taking note of details. They’re definitely more interesting than his stories, largely because they excise the things he’s the worst at.

But I don’t see anything that’s comparable intellectually (in words or pictures) to what Jeff Wall is doing in that essay I linked to above, or to Delany’s readings of science fiction and post-structuralism or his writings about race or Rushdie’s reading The Wizard of Oz. Ware’s still avoiding that step where you take all the observations, look at them from one step back, and come up with an original insight that links them all together. I think Noah’s right that there are just some kinds of thought that you can’t do quite as well in pictures as you can in words, and critical analytical thinking is probably one of them.

This does not mean, Noah, that you have to like Rushdie. Pfft. The Nabokov comparison works very well.

I think there are analogues to critical analytical thinking that you can do in pictures — Jeff Wall is an example of someone who does that, actually. I think it’s not something you see a lot of in comics, though…whether for formal or historical or other reasons I don’t know.

Rob, I also think that your description of the relationship between criticism and art just doesn’t reflect a full historical picture. Look at the role Apollinaire played for Surrealism, or the function of criticism in Dada and Futurism. Henry James called the critic “the real helper of the artist, a torch-bearing outrider, the interpreter, the brother.” John Cassavetes threw Pauline Kael’s shoes out a cab window he was so angry with her one time — but notice that they were nonetheless in a cab together, presumably talking about art.

Post mass culture, the critic does tend to be isolated from the artist in the way you describe, but I think that’s to the detriment of artist, critic, and art.

Caro: ” I’d be on board with what you’re saying if I thought Ware would be satisfied with being described as “the cartoonist who does interesting experiments with visual representation of time and space.”

Oh, he wouldn’t be satisfied at all.

Which is why I think the line: “He rarely sets himself artistic tasks he cannot execute flawlessly.” is not entirely accurate since he clearly struggles considerably (and only occasionally succeeds) with the emotional aspects of his art. A number of the artists he praises in public pay very little heed to the formal aspects of comics and focus on just that.

I’m guessing that as an artist he realizes that the realm of ideas and stories has been so thoroughly mined over the centuries by other art forms that any novel expression of them needs to be communicated through the peculiarities of comics. The question is whether these techniques add anything to the reader’s experience of these familiar stories. I suppose in Noah’s case, the answer would be a resounding “no”. I think he has succeeded a handful of times.

As for Midnight’s Children, it is probably the best book Rushdie has ever written (at least up till 2000 which is the last time I picked up a novel/collection by him). I think it’s perfectly fair to compare the absolute quality of that book against Ware’s achievements in comics.

However, I think you’re reading too much into people’s praise of Acme or really any comic (Krazy Kat, Little Nemo etc.) at all. No one is really claiming that Jimmy Corrigan is better than Midnight’s Children or that Krazy Kat is as important to Western civilization as Bach (at least, I hope they’re not). And even if Rushdie is a bad comparison as far as formalism is concerned, I still much prefer Life a User’s Manual or If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler to anything Ware has done recently (I find Nabokov pretty sterile so won’t use him as a comparison).

What the critics are probably saying is that Chris Ware is as interesting an artist as a number of his contemporaries in British/American letters and deserves some attention. Which means I’ll rather read Acme than Ian McEwan’s Amsterdam, Arundhati Roy’s God of Small Things or Yann Martel’s Life of Pi – all of which “inexplicably” got heaps of praise thrown at them and won the Booker like Rushdie’s book.

Comics are still very much in their adolescence as an art form. It will still be at that stage by the time I die. Ware is simply developing some of the building blocks and he’s better at it than most of his peers. He’s getting accolades for that.

Noah: One of my favorite Chinese brush painters is Bada Shanren (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bada_Shanren) and he has some similarity to the Zen artists you’re talking about. They both derive (sort of) from a common root in Chinese ink painting during the Tang and Song dynasties.

I think Jeff Wall’s no slouch on the critical prose front, given that essay I linked to. I’m sure the line between thinking in English and thinking in pictures is very blurry and seamless for him; I don’t think this a clear translation process, but he’s definitely not rejecting natural language as a mode for analytical thinking to nearly the same extent as Ware.

Suat: “I’m guessing that as an artist he realizes that the realm of ideas and stories has been so thoroughly mined over the centuries by other art forms that any novel expression of them needs to be communicated through the peculiarities of comics.”

If he really does think this, that’s an incredible cop out. If it were true, there were be no point in any writer ever writing another prose book. Again, it’s really hostile toward writers.

I think the point is more your following sentence — not so much whether, but how to make “the techniques add anything to the reader’s experience of the familiar stories.” But that’s still basically formal experimentation, isn’t it? If there’s no imaginative contribution except in technique?

I completely agree with you that Ware is providing building blocks (although I also am not sure he’d be happy with that limited description); however, I think that his attitude toward criticism is even more unfortunate in that instance as we would all benefit if he wrote about what he was doing and triggered conversations about it. The problem is that unless someone abstracts what he’s doing into prose, it can only enter into conversation as “influence.”

Visual artists who experiment often do write about their experimentation and what it means: Wall does, Cocteau did, Picasso did, the Cahiers du cinema writers were almost all artists. A body of prose critical work like Wall’s by Ware would be tremendously beneficial for comics. Unfortunately he just doesn’t seem to be able to write prose at that level.

Oh, forgot to say: I think McEwan, Roy and Martel are examples of the difference between the critical marketing machine and more serious criticism: they got heaps of praise poured onto them the year they came out, but it didn’t hold up over time. Rushdie took the Booker for the decade and still pops up. (I’d argue MC is not only Rushdie’s best, but the best book in English since Invisible Man.)

Praise for Ware does keep coming over time. And he deserves a lot of it. But nobody pulls their punches on Rushdie’s weaknesses, and I don’t see why we have to on Ware’s either…

Thanks for the link to Bada Shanren, Suat. Just lovely.

“No one is really claiming that Jimmy Corrigan is better than Midnight’s Children or that Krazy Kat is as important to Western civilization as Bach (at least, I hope they’re not).”

I won’t make any claims for Jimmy Corrigan or Krazy Kat…but I think Peanuts is pretty unimpeachable as great art by any standard, damn it. Definitely better than Rushdie, and I prefer him to Bach (though I do like Bach quite a bit.)

That is, I prefer Schulz to Bach. Not Rushdie to Bach.

Okay, bed now.

I think it’s actually #2—Everyone calls it #10 because of the giant 10 on the cover–but it says 10 cents, not #10. Could be wrong about this, but I’m not:-)

My favorite ad in the issue is for the hilarious cardboard cutouts of the “happy family” that you can put in your window, while you continue dysfunctionally drinking, abusing, etc. etc. behind the cardboard.

I think the Harold Bloom thing works great on someone like Grant Morrison (who clearly operates largely in response to Moore himself), but not really on Moore himself or Ware.

Also, while Ware is capable of being very funny, most of the Jimmy Corrigan GN is not–and not aiming to be. That’s a pretty major difference between Ware and Schulz.

Charlie Brown also gets his licks in occasionally–He deflates Lucy from time to time, good-humoredly mocks himself, has friends (primarily Linus, but also importantly Snoopy for whom he plays the Dad role)–He’s (ironically) just a more fully complex character than JC (that’s Jimmy Corrigan, not Jesus Christ) and therefore never JUST the depressing butt of the joke.

E

Rushdie hasn’t done anything since 2000 to change your opinion Suat. I do think Satanic Verses is a pretty close rival to MC though.

I think the most directly telling thing on that cover of TCJ Ware did is right there in the actual title itself:

“The MAGAZINE of NEWS, REVIEWS, and MEAN-SPIRITED BACK-STABBING.”

Eric: Yeah, SV and MC are the best two. I keep wanting to like Fury and not being able to. I do like Haroun and the Sea of Stories, though…

And the corrective to the comparison of Ware and Schultz is apt, I think. Ware’s anxiety of influence may be sadly not Peanuts, the masterwork, but a mental impression of Schultz the Man, How to be a Cartoonist in 50 Neurotic Years.” The next Ware monograph should be entitled “Spectres of Schultz.”

It really is 10! There’s this anthropomorphic globe on the cover reading a comic book. I can’t find the happy family, though, so that might be in 2…

Michael, do you know, did The Comics Journal write something that pissed Ware off, or is this “critics are mean” schtick just his idea of a quip? I remain concerned that he actually really does think that critique is mean…

It’s a quip. I’m sure there have been negative reviews of Ware published in the Journal, but on the whole it’s been pretty enthusiastic. I think he was listed as 3 or 4 on the all time greatest cartoonists ever list (after Schulz and Herriman…and maybe somebody else — too lazy to look it up.)

Now that I think it, I’m surer than sure that there was some negativity in the journal, because of this.

Yeah, I figured as much. Is it really actually possible that he doesn’t realize how incredibly LAME that schtick is?

And it’s there in the McSweeney’s issue too. And I heard his Pen Faulkner lecture, and he talked about it there too.

It’s serious, repeated, anti-intellectualism, yet intellectuals bend over backwards to praise him. I don’t get it. Are we just all afraid he’s going to cry?

It’s obviously all your fault, Noah.

Ed Howard’s comment there about too many people picking Ware’s characters over his formal experimentation to be interested in is pretty apt I think.

I’m curious to see the new book that Kent W. reviews over at the parent site today; it sounds like the academics are for the most part emphasizing the formalism, which is appropriate. The last essay sounds like it’s trying to make it about social justice themes, and that really probably ain’t gonna work a’tall.

Intellectuals hate intellectuals too, you know. We’re just like everybody else.

There are social justice themes in his work, as I said over there. They’re just kind of dumb….

Yeah, but when an intellectual hates intellectualism, it’s self-loathing. Which is boring and pointless in an intellectual just as much as is in anybody else. And Chris Ware tries to make a virtue of it.

There’s also just a dripping amount of the worst kind of irony when he tries to base a rather hostile anti-intellectualism on the idea that we’re too mean. It’s, again, very passive aggressive.

I agree his social justice themes aren’t terribly interesting, but I also think that it gets back to the problem I originally identified: he just hasn’t figured out how to move beyond themes to thesis while relying entirely on the formal structures of pictures to do the idea work. The last essay is arguing that the themes tie together into some overall point, and I think Kent’s right to ask for textual evidence of that. I think that’s a different issue of whether his themes are dumb or not (although, yeah, they are).

That themes v. thesis business may be why Ware lands on this idea that art shouldn’t be about ideas, because it’s really hard to make pictures into very elaborate theses, because it’s hard for them to do the kind of logical argument work that words can do. Argument is math, and math is based on non-indexed abstractions, the exact opposite of the indexed concretizations of comics images. Whereas words are abstract enough that they can be stuffed into logical structures, pictures resist that — they properly resist that. It’s a killing flaw to me in the way Ware conceptualizes his work.

Caro, I’ve really no idea.

I can’t imagine that TCJ hasn’t at some point printed something by someone re: Ware and his work that DIDN’T rub him wrong.

He certainly wouldn’t be alone in that regard.

It does make me wonder if he and TCJ spoke about that bit of content beforehand or not. Either way, it implies that TCJ can take a shot with a good deal more grace and decorum. It takes a bit of stone to allow someone to turn your tag-line/mission statement back on itself in such an incriminating manner, tongue-in-cheek or not.

I can barely make out the rest of the blurbs at the bottom of the cover, but much of that seems to be a little mean-spirited too. So much so that I have a hard time believing it wasn’t in the spirit of fun.

That all said – were they ALL Ware’s words, or not? Were they meant as a friendly jibe, or was there something else underneath/behind all that?

I guess we’ll have to ask Chris Ware himself, or Gary Groth maybe.

eric b, it’s Acme #10. Never doubt me in mathy things.

And one more thing on the root of Ware’s hatred of critics… The conversation here’s mostly from the horsefly world of litcrit. But in Acme #10 (I think) there’s a page ad for “Art School” where he lashes out against art critics, grantwriting, taking a dump in a jar. It’s both very funny and very much like a pissed undergrad who just wanted to draw people when figuration was out of style. And never wanted to explicate his work. Yet Jeff Wall has very good reasons to write well (not just that he’s 20 years older than Ware and thinking on legacy), because artist statements and an essay in Artforum can get you a grant or tenure or a solo show. Ware’s managed to skirt all that, in part by working in a popular form closer to Twilight (the books, the movie) where criticism’s for marketing blurbs.

I know he’s had gallery shows– they were still giving out his foldout map at MCA in Chicago a couple of years ago. Yet I don’t know what the reception’s been.

The apotheosis of Ware’s anti-critic whining is probably his guest-appearance in that horrible Jeff Brown comic, where he’s dragged onstage to tell Brown how wonderful he (Brown) is and how he shouldn’t listen to critics because they’re all stupid.

Bill, Chris Ware is pretty thoroughly validated by the art world at this point, I think. He did the cover of the Whitney Biennial, he appears in shows with some regularity, etc. etc. They love him too.

Noah–

I think you’re taking Bloom’s “anxiety of influence” trope too literally. I personally don’t care for the way he uses Freudian terminology to explicate the concept, largely because it has led to all sorts of misunderstandings. I personally prefer Hegel’s “Lordship and Bondage” paradigm to explicate it, and he told me that if I saw it in those terms, I understood it better than probably three-quarters of the people out there.

But Moore certainly is an anxious writer in the way you mean. The guiding creative goal behind Watchmen and From Hell is to create a superhero story or piece of historical fiction that Kurtzman wouldn’t call bullshit on. Or, more to the point, they’re designed as pieces that Kurtzman would be too intimidated to call bullshit on. There is an artistic Oedipal conflict in the way Moore approaches his work.

Like Kurtzman, Moore interrogates the discourses of the material for absurdities. From there, they both create a pastiche of the material. Kurtzman, though, uses the absurdities as a source of humor. Moore’s approach–his way of beating Kurtzman–is to correct or avoid the absurdities in order to make the material more dramatically effective. That’s his “misprision” or “achieved anxiety” with regard to Kurtzman’s work.

“Anxiety of influence” is not about repeating the licks of a predecessor. It’s about beating a predecessor at his or her own game, largely by changing the rules. The goal is to make the predecessor look inferior in some respect. And to once again invoke the dreaded Freudian terminology, it’s borne of drive and desire, and for the most part isn’t deliberate.

On some level, Ware seems to have decided that the way to beat Schulz is to take Schulz’s distilled narrative and visual strategies but use them in a more novelistic way. The individual panels retain the same austere simplicity, but far more of them are used to render a scene, generally to incorporate a greater range of nuances in pursuit of more complex effects. To go back to my earlier analogy, his work is like someone trying to rewrite In Search of Lost Time or The Wings of the Dove using Hemingway-style sentences.

I personally can’t stand what Ware does, even though I recognize and respect his ability. What Moore does strikes me as a healthy reconfiguration of Kurtzman’s artistic strategies. Ware’s work strikes me a neurotic, pathological effort to not only beat Schulz, but to frighten off anyone who might think about competing with his own efforts. It’s like he’s trying to create a monument to his own abilities, rather than to communicate or entertain. Joyce was like this, too, but you generally got the feeling that, unlike Ware, he enjoyed life. Ware is just insufferable.

It doesn’t surprise me that Eagleton would say that about Bloom. They’re mutually opposed. Bloom sees art as predominantly the efforts of exceptional individuals; the history of art and literature is how those individuals develop from each other. (His mentor was Northrop Frye, who I think you’re familiar with.) Eagleton’s work has always been about seeing art as an expression of societal ideology. He’s a Marxist, and it goes against the Marxist grain to lionize individual achievement the way Bloom does.

Has Moore ever talked about Kurtzman in this way? I mean, Moore kind of does lots of different things and uses lots of different folks as touchstones — it’s just weird to me to point to one person and say, this is where it’s all from.

You’re definitely right about Eagleton and Bloom; I much prefer the former. You should check out his London Review of Books take on Bloom’s recent stuff though; not sure if it’s online, but it’s pretty powerfully funny.

Bloom is so, so, so Freudian. Even his socks are Freudian. His denial of Freudian influence (if he does so) would only make him all the more Freudian, you know?

Ware’s austere simplicity is fairly different from Schulz’s. Schulz never was, or tried to be perfect; his drawing (especially pre-stroke) was really incredibly lively. I guess they were simple but often not exactly austere; there’s just a lot of joy and energy in his drawing in a way that Ware often (especially recently) deliberately eschews….

There’s a lot of Stan Lee and Thomas Pynchon in Moore, too, but Kurtzman’s approach seems to be the one he’s most preoccupied with and has done the most to build on.

Moore has said on any number of occasions that a key influence on his thinking with Watchmen was Kurtzman superhero parodies like “Superduperman.”

Yes, Professor Bloom is very Freudian. He talked about Freud all the time in class. He even said a therapist stopped seeing him because he knew more about Freud than the therapist did. I took a “Freud as Literature” course the following semester because he kept losing me with the constant references.

The austerity in Schulz and Ware is different. With Schulz, it’s more in the composition than in the rendering. He gradually distilled almost all the elements down to 2-D forms. And his line has a definite verve, before and after he developed the shakes. Ware’s stuff looks like it was stamped out by a machine, which is another reason I can’t stand looking at it. It’s like he thinks personality is a sign of weakness or something.

I think Robert’s comment

articulates some of the mechanism that is interfering with the “complex effects” that Ware is seeking, at least insofar as he actually is going for “novelistic” effects rather than purely visual ones. So much of what makes novels complex depends upon the mixing together of both logical and allusive interplay, with both imagery and abstract concepts involved in the interaction.

Ware apparently thinks he can translate this interplay to a medium that relies on those “indexed concretizations” I mentioned above, and I appreciate his work as an experiment in that direction. But the problem is that complexity in ideas requires some degree of abstraction, and his work, as you rightly point out, is so concrete that it appears stamped out by a machine.

I think that’s why so much is lost when it’s translated into prose: there isn’t any actual abstraction there to capture, there is only the suggestion of it. Ideas are themes in Ware, not structural pillars. Again, I think this is a killing limitation to his project.

Hey, speaking of abstractions, has Ware commented at all on the Abstract Comics book? I think THAT project is actually making much more headway toward finding a way to mitigate the concrete reification effect that comics is so prone to and that characterizes so much of Ware’s work. But it’s almost aesthetically opposite…

Yes! Abstract Comics is a work of genius!

At least certain pages anyway. If you know what I mean.

I can say I understand Harold Bloom pretty well (though never having met the man personally–as Robert is at pains to make clear he has (anxiety of influence anyone?)) Moore talks plenty about Kurtzman’s influence–and Crumb’s–and Kirby’s (seen the Supreme issue)–and Steve Moore’s—and Eisner’s (seen Greyshirt)–and Brian Eno—and Jack Trevor Storey–and William Burroughs (and on and on). Moore also has done plenty of pretty straightforward Kurtzman pastiches—in Tomorrow Stories, especially, but also in his early work. The notion that he is “misrecognizing” Kurtzman in order to “kill him” in the Freudian/father-killing pscyhoanalytic way is even sillier than Keats “misrecognizing” Milton in order to do the same. Bloom is a smart guy and a good writer–so he can pull off this kind of analysis… I like the idea as a fun way of thinking about literary history–but that’s about all it is in my mind. It might apply to a few creators here and there, but as a structuring principle for literary history (or for comics history–and esp. for Moore and Ware in this case), it ‘s pretty limited. Might make for an interesting Master’s thesis on a few comics creators–but it’s more than a little overdetermined (to use more psychoanalytic lingo)–and not in a good way.

Sounds like Moore’s is an Ecstasy of Influence, (to borrow Lethem’s term).

I thought Robert’s take on the Kurtzman/Moore connection was certainly worth thinking about. I don’t really buy it, but it’s an interesting perspective, which is probably what Bloom is mostly useful for.

In any case, please refrain from psychoanalyzing your fellow commenters, if you would.

I’m thinking about the ecstasy/anxiety of influence stuff alongside the reception Ware gets from art society and wondering how much of his allergy to criticism is connected to this idea that everybody needs to say great things about comics and praise comics because they’re this ghettoized art form. I’m wondering if he has the idea that if we all praise them constantly people will start thinking they’re important.

Ware’s largely uninterested in mass culture and I wonder to what extent he realizes that the artists who can take the punches (and art forms that attract them) are generally more respected than the ones who can’t and don’t. I’m thinking particularly of Eminem, who either shrugs it off entirely or comes back with a wittier-than-thou line to take the piss out of it. That’s much more Cocteau’s attitude than Ware’s.

That seems to be one of the differences between ecstasy and anxiety of influence — the ecstatic folks can be aggressive about their influences, but they’re rarely passive aggressive. There’s something really dishonest about being as aggressive as Ware and yet coating it with this veil of courtesy and politeness. It’s very artificial, but every trace of camp enthusiasm has been eradicated. So it is very old-fashioned, in that there’s a veneer of mannerliness with so much frustration simmering under the surface.

The ecstatic folks in contrast aren’t trying to prove anything, they’re in it for the joy and love. So they can be camp when they choose to defend against something, or they can just be enthusiastic (if they’re grown up enough to have escaped the prisonhouse of irony…)

There’s a little bit more of that ecstasy in Seth, for example. The comic he has in the McSweeney’s 13 touches on some of the same themes about fandom as Ware’s TCJ 200 cover, but Simon gets such a sympathetic an inner life, the talking toys, the affectionate narration about his collection. Contrasting it with Ware’s piece in the same issue (about the girl whose lover abandoned her) really highlights how stingy Ware’s tiny panels are: even the fairly small panels in the Seth cartoon seem lush in comparison. Neither is exactly optimistic, but Ware’s “past” and “memory” are Dementors sucking the joy out of his character, whereas Seth is much more deft at capturing the ambiguity of the past-as-nostalgia, memories that hold you back because they were so pleasurable it’s sad to lose them.

That said, the comic on God in the cover of that issue is one of my favorite Ware pieces — I still don’t love it but I like it — for two reasons: 1) God is an abstraction, so there’s a little more room for connecting dots, plus God gets drawn with abstract-y mid-century modern style. This is a) something I like period and b) pared down enough that a 1 inch square panel of it doesn’t feel stingy. Also it’s so much more honestly aggressive; it’s really actually a little bit mean.

Of course, he has the girl character condemn it as “self-indulgent and arty” at the end — she wants more interesting characters. more interesting characters than GOD and his pet cartoonist — and that sort of undermines the small bit of enthusiasm he managed to work up by representing his own anxieties about being a cartoonist. But it is a counterexample to the complete bleakness. If he wrote like that all the time I’d think he was entertaining. I still wouldn’t think he was Rushdie, but I’d think he had potential. E

Everything ELSE I’ve re-read in the last 24 hours I think is subject to the same critique I made at the beginning. Sorry, Matthias.

Ware did have a strip about an online comics critic posting an essay about what a sad, pathetic little world superhero fans live in and then thinking, “Oh, boy! Someone already commented on my essay!” I don’t know whether that’s better or worse than, “And Moby, you can get stoned by Obie/You 36-year-old, baldheaded fag, blow me.”

Ware’s is definitely worse. Eminem’s has Dr Dre as Batman.

I’m not really that big a fan of Eminem, but it — that song in particular, in fact; excellent job of reading my mind — really strikes me as a much funnier and campier and more honest way of dealing with similar anxieties to the ones that show up in Ware’s work. That’s probably just rehearsing the same old “middle-class anxieties are less convincing than working-class anxieties” thing, though.

I’m one of the only people in the world who is a huge fan of both Mr. Ware and Mr. Mathers. If only one day they could collaborate…

See, that could be great! They might bring out the best in each other.

And I think it’s perfectly consistent. I am not a fan of either, although I have more data points indicating passable enjoyment for Slim.

Your essay and the discussion inspired by it are keenly exciting. But I would suggest a different, possibly more charitable reading of Ware’s letter to The Imp.

As I read him: What Ware objects to is not (analytic) criticism as such but “easy” criticism. (After all: He is complimenting Daniel Raeburn for having “done what most critics . . . find most difficult” and therefore often fail to do.)

Ware objects to poor (“easy”) criticism because, unlike Raeburn’s, it tends to leave the actual work behind, to forget the particulars of the work and what they achieve (e.g., “a life or a sympathetic world for the mind to go to”). Instead, such criticism focuses on the ideas and theories (social, literary, political, metaphysical, etc.) that it takes the work to illustrate or express.