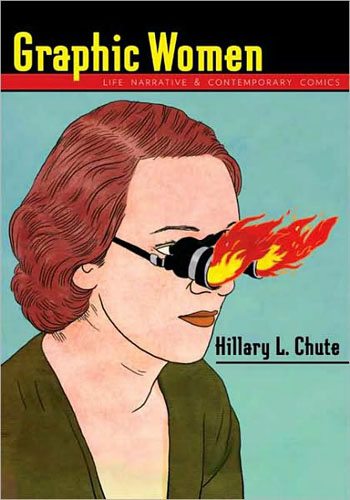

“Is it autobiography if parts of it are not true?” Lynda Barry asks this question in the introduction to her 2002 book One! Hundred! Demons!, and Hillary L. Chute quotes the panel in her book Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics (Columbia University Press, 2010). Ever since she co-edited the special issue of Modern Fiction Studies on “Graphic Narrative” in 2006, scholars have been eagerly awaiting the publication of Chute’s monograph, based on the doctoral dissertation that she completed at Rutgers University. Reading her work recently led me to a number of questions about comics, gender, and autobiography, not the least of which comes back to the question suggested by Barry.

“Is it autobiography if parts of it are not true?” Lynda Barry asks this question in the introduction to her 2002 book One! Hundred! Demons!, and Hillary L. Chute quotes the panel in her book Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics (Columbia University Press, 2010). Ever since she co-edited the special issue of Modern Fiction Studies on “Graphic Narrative” in 2006, scholars have been eagerly awaiting the publication of Chute’s monograph, based on the doctoral dissertation that she completed at Rutgers University. Reading her work recently led me to a number of questions about comics, gender, and autobiography, not the least of which comes back to the question suggested by Barry.

Autobiography is, by far, the most consecrated genre of comics within the American academy. Hundreds of articles have been written on Art Spiegelman’s Maus, and a growing number have been published on Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis. The squeamishness that many academics – and academic departments – have about comics is mitigated to some small degree by the growing body of comics on self-consciously serious topics. When comics are easily slotted within existing scholarly frameworks – feminist life-writing, studies of the diasporic communities – they are more likely to be included on college syllabi. Chute’s book shares in this logic, marshaling a quintet of serious, theoretically-nuanced critical readings of important autobiographical comics by women: Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Phoebe Gloeckner, Lynda Barry, Marjane Satrapi, and Alison Bechdel. Chute brings various lenses to her analysis of these artists, but the most frequently invoked is trauma. By selecting artists who chronicle troubling sexuality (Kominsky-Crumb, Gloeckner), geo-political meltdowns (Satrapi) and the disintegration of the family (Bechdel), Chute’s book tends to affirm the perception, so prevalent since the success of Maus, that important comics are those that deal with important topics.

Situating the origins of female autobiographical comics at the intersection of the (primarily male) American underground comix scene and the path-breakingly feminist responses to it found in Wimmen’s Comix, Tits and Clits, Twisted Sisters and other anthologies, Chute’s book moves effortlessly through the work of her subjects, offering new readings and insights while all the while building a case for these autobiographical comics to be read as literature. In her final chapter, for example, Chute argues that Bechdel’s Fun Home “is a prime example of how the form of comics expands what ‘literature’ is in a way that puts productive pressure on the academy, the publishing industry, and literary journalism” (178). For Chute, these pressures stem from Bechdel’s artistry, from the way that Fun Home is structured around references to modernist literary works, and from the way that it eschews a straightforward chronology (as in Persepolis) for a more nuanced way of retelling her own history, and that of her father.

Situating the origins of female autobiographical comics at the intersection of the (primarily male) American underground comix scene and the path-breakingly feminist responses to it found in Wimmen’s Comix, Tits and Clits, Twisted Sisters and other anthologies, Chute’s book moves effortlessly through the work of her subjects, offering new readings and insights while all the while building a case for these autobiographical comics to be read as literature. In her final chapter, for example, Chute argues that Bechdel’s Fun Home “is a prime example of how the form of comics expands what ‘literature’ is in a way that puts productive pressure on the academy, the publishing industry, and literary journalism” (178). For Chute, these pressures stem from Bechdel’s artistry, from the way that Fun Home is structured around references to modernist literary works, and from the way that it eschews a straightforward chronology (as in Persepolis) for a more nuanced way of retelling her own history, and that of her father.

Despite the many strengths of Chute’s analysis, I was left to wonder how her framework could address the most celebrated of recent French female autobiographical cartoonists, especially Judith Forest. Forest exploded onto the comics scene in 2009 with the graphic novel 1h25, published by Cinquieme Couche. Taking its title from the length of time needed to go from Paris to Brussels on the Thalys train, Forest recounted her sexual, social and artistic exploits in a whimsically diaristic fashion. While her book touched on dark aspects of her past and present – including drug use, and an uneasy relationship to her father that plays out over email – the overall tone is light-hearted. Her trips to the Angouleme festival are recounted, as are her meetings with cartoonists like Ruppert and Mulot, Francois Olislager, and Xavier Lowenthal, with whom she has an affair.

Forest’s book sent a shockwave through the French comics scene. Her work was widely reviewed almost unanimously praised. I myself picked her book as one of the most interesting of the 2010 Angouleme festival, at which she was notably not present. She was interviewed frequently on the radio, and even on the television channel Arte. In short order she had become the newest French comics superstar. Over time, however, the most unusual thing happened. Rumors began to abound that Judith Forest did not actually exist. Cartoonists depicted in 1h25 denied having met her. Wasn’t it strange that she appeared at so few festivals? Hadn’t you noticed how much her art reminded you of William Henne, one of the publishers of Cinquieme Couche? Wasn’t it odd that the artist that she seemed closest to in the book, Lowenthal, was also a publisher of Cinquieme Couche?

Forest’s book sent a shockwave through the French comics scene. Her work was widely reviewed almost unanimously praised. I myself picked her book as one of the most interesting of the 2010 Angouleme festival, at which she was notably not present. She was interviewed frequently on the radio, and even on the television channel Arte. In short order she had become the newest French comics superstar. Over time, however, the most unusual thing happened. Rumors began to abound that Judith Forest did not actually exist. Cartoonists depicted in 1h25 denied having met her. Wasn’t it strange that she appeared at so few festivals? Hadn’t you noticed how much her art reminded you of William Henne, one of the publishers of Cinquieme Couche? Wasn’t it odd that the artist that she seemed closest to in the book, Lowenthal, was also a publisher of Cinquieme Couche?

Initially, these rumors seemed unfounded. Sure, there was a similarity between Henne and Forest, but there is a similarity between David B. and Satrapi, and no one suggests that he drew Persepolis. And besides, hadn’t we seen her on TV? Wasn’t I her Facebook friend?

This year at Angouleme, Forest released her second book, Momon. Dedicated to “all those, and most especially the journalists, who allowed me to exist”, the book traces the success of 1h25 before revealing that Judith Forest does not, in fact, exist. A creation of the editors of Cinquieme Couche, she is a fictional character played on the radio, television and Facebook by the actress Sabrina Lucot. Her exploits are entirely invented, as are her thoughts.

This year at Angouleme, Forest released her second book, Momon. Dedicated to “all those, and most especially the journalists, who allowed me to exist”, the book traces the success of 1h25 before revealing that Judith Forest does not, in fact, exist. A creation of the editors of Cinquieme Couche, she is a fictional character played on the radio, television and Facebook by the actress Sabrina Lucot. Her exploits are entirely invented, as are her thoughts.

In retrospect, the clues were all there. Early in 1h25 Forest writes “I’m not good at fiction,” but that is just not the case. Forest’s art teacher lectures her that the artist is the “supreme conspirator” and that an important relationship exists between art and mystification. Later she reminds us that there is a “constant fracture between a being and her story, between her desires and her life.” 1h25 is revealed to be a conjuring into existence of both a story and a person; one that is terribly convincing.

Of course, this is not the first comics fiction to have passed itself off – however briefly – as fact. My students are always disappointed to learn that Seth’s It’s a Good Life If You Don’t Weaken is a work of fiction. Autobiography scholar Philippe Lejeune has written extensively of the “autobiographical pact,” in which the “I” of the narrator is presumed to be a truth-telling subject. Perhaps in the wake of the James Frey and JT LeRoy scandals we have learned to be skeptical of the distinction between autobiography and fiction, noting, as Barry does, the considerable overlap between these categories. In Momon, Forest writes “all biography is a fiction, a lie, a fraud.” This stance seems harsh to me, but what does seem key to me, in contradistinction to Chute’s emphasis on autobiographical comics as literary, is that all autobiography is performative. The creators of 1h25 seem to be fully cognizant of this fact. While Chute astutely notes, as a way of defending women’s legitimacy as artists, that the two most celebrated comics of the past ten years —Persepolis and Fun Home— are autobiographies by women, Forest’s creators note it only to undermine and exploit it. Indeed, they have created a self-consciously literary work as a meta-referential critique of the very notion of literariness in comics. Chute’s argument is the first step in allowing scholars to unpack these highly charged dynamics.