Phoebe Gloeckner pretty much interviews herself. As a writer and artist, she is the author of the comics and art collection A Child’s Life and Other Stories; the comics/prose/illustration hybrid The Diary of a Teenage Girl (adapted into a film by Marielle Heller in 2015); and an as-yet-unfinished multimedia project on the family of a murdered teenager in Juárez, Mexico that she’s been working on both at home and abroad for over a decade. As an associate professor at the University of Michigan, she seems to relish the opportunity to work with young cartoonists as they discover their own voices. And as an interview subject, she has a discursive, recursive way of making connections between different aspects of her practice and experience, then circling them over and over until she draws out the meaning she’s looking for. If she feels she hasn’t succeeded, she’ll be the first to tell you.

Phoebe Gloeckner pretty much interviews herself. As a writer and artist, she is the author of the comics and art collection A Child’s Life and Other Stories; the comics/prose/illustration hybrid The Diary of a Teenage Girl (adapted into a film by Marielle Heller in 2015); and an as-yet-unfinished multimedia project on the family of a murdered teenager in Juárez, Mexico that she’s been working on both at home and abroad for over a decade. As an associate professor at the University of Michigan, she seems to relish the opportunity to work with young cartoonists as they discover their own voices. And as an interview subject, she has a discursive, recursive way of making connections between different aspects of her practice and experience, then circling them over and over until she draws out the meaning she’s looking for. If she feels she hasn’t succeeded, she’ll be the first to tell you.

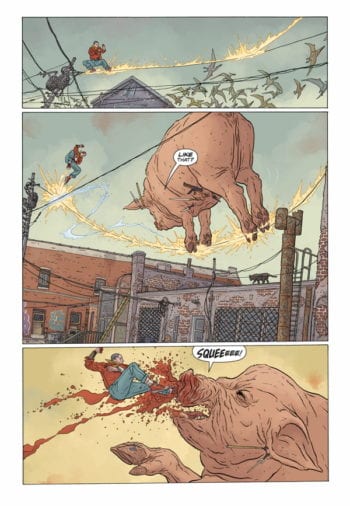

This makes her a fascinating choice of guest editor for this year’s volume in The Best American Comics anthology series, co-edited as usual by Bill Kartalopoulos. Such anthologies, after all, have the meaning assigned to them right in the title: These are “the best” comics of the year in question, at least out of those that were submitted for consideration. Yet they also place a disparate range of cartoonists, styles, and subgenres between two covers—an implicit challenge to the reader to determine their common ground. Gloeckner’s choice to arrange the work alphabetically by author amounts to doubling down on this challenge: What does a harrowing autobiographical piece by Gabrielle Bell have in common with an excerpt from Geof Darrow’s action extravaganza Shaolin Cowboy featuring a talking killer pig? Well, she happened to like them both, Gloeckner might say…and then spend five minutes autopsying that statement, until not only the comics themselves but also the very concept of determining the quality of a comic have been explored inside and out.

What have you observed as a teacher about where comics is headed, based on your students? By virtue of being a teacher, you must have been following trends on the ground, in terms of what your students are interested in.

Surprisingly, it’s a slow movement. When I think of how I learned to do comics, and what I was writing about, and what they’re writing about, and how they’re working, it’s not that dissimilar.

You get some students who, because they’re so young, grew up perhaps reading manga and watching Family Guy, or grew up with Disney or Pixar, so a lot of them have aspirations to be animators or writers for Pixar. I don’t know that I knew anyone with such aspirations when I was a kid—I guess it would have been Disney then—but that certainly is a draw. You see in these really young students a tendency to mimic styles. But I really don’t think that’s unusual in any field for young people, because that’s how they learn. They love something, so they try to emulate that, so they can become a part of it somehow. Gradually, if they’re lucky, they’ll recognize that their genuine voice is perhaps a little different, and they’ll gain confidence and go off in other directions.

Then you get the more independent, more rebellious types, who are reading independent comics and are interested in things that are harder to find. But a lot of times, because they’re 19 or 20 years old, they’re very conscious of whether or not something is “cool.” That makes them self-conscious and judgmental, and closes them down. To some extent they’re all closed down, because they don’t have confidence and they’re trying to be one thing in particular or another. I see it more as like, you have them at a developmental stage, which is really important, so you just try to encourage them to read a lot, and to teach lots of different comics and think about how stories are told.

But sometimes I see my role as just helping them find what their real strengths are and figure out who they are, what their voice is, because they don’t really know. They’re young! There are very few writers or cartoonists that arise from the ocean fully formed in their late teens or twenties. Musicians might do that, but I think it takes more living to become a good cartoonist in particular.

That didn’t really answer your question, because you’re asking me do I see trends—you’re asking something more about topical style, directions and things. I’m aware of it, but I don’t give it a whole lot of importance in teaching.

To backtrack a second, where are you teaching, and what are you teaching, and who are you teaching?

I teach at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and I teach college students, most of whom are art students. I have a comics class, and then I have another class called “The Illustrated Book,” which is really writing and illustrating but not so much comics. It’s more prose and illustration together, but they’re doing everything. In each of those classes, they’re both writing and drawing in different ways.

Because I’m essentially the only person who is teaching comics, it’s difficult. I always start out with all these huge aspirations, like I’m gonna expose them to a million different styles and the history of comics and everything else, and then they’re gonna make three five-page stories, and they’re gonna do this and this. I mean, comics is just doing comics. As you know, it’s not just drawing and writing—it’s designing pages and a million other considerations and skills that are necessary to make them. It’s really unrealistic to pretend that I could give them a whole history ,or even a complete survey of what’s going on in the comics world [right now], or what has in the past. I mean, I can’t. It’s not possible. But I always want to.

In a way, it’s actually good: I assigned Best American Comics this year, and since I had something to do with choosing the comics, they have something fun that we can talk about: “Why did I choose this and not that?” In that sense it’s a pretty good way to give a survey. But again, it’s a representation of what was submitted. In a sense it’s a lie, because we certainly did not read every comic that came out last year. It’s not possible.

No one can.

Half the people who have done comics don’t even know about this book. I never would have submitted anything to it; I never have. It just wouldn’t have occurred to me. I would have just imagined they wouldn’t have taken my stuff anyway. For whatever reason—if people are insecure, or they just don’t read these things, or they’ve never heard of it—they’re just not gonna submit their work. So then you probably won’t see it, unless they handed you a minicomic at some obscure convention. Accepting that, that it’s an imperfect process that’s kind of impossible, it’s still a good collection of stuff that came out last year.

Julia [Gfrörer] and I put out an anthology last year, but it was very different because it was all invitational, and we had a particular vision in mind when we reached out to people. It’s a survey of stuff that we’re interested in and stuff that we like and think comics should do, but it’s not, “Here’s the length and breadth of comics as we know it,” which is sort of the Best American remit.

Julia [Gfrörer] and I put out an anthology last year, but it was very different because it was all invitational, and we had a particular vision in mind when we reached out to people. It’s a survey of stuff that we’re interested in and stuff that we like and think comics should do, but it’s not, “Here’s the length and breadth of comics as we know it,” which is sort of the Best American remit.

Right. The editors can invite people to submit stuff, but there’s so much that is submitted, that there’s so much to read anyway. That’s the other thing: You can be tastemakers because you’re choosing the potential candidates for your book, but it doesn’t really work that way with this book.

There’s also the issue of…Like, I know a lot of cartoonists, so if someone submits something and you love their work but maybe what they submitted this year isn’t blowing your mind, it hurts to not include it. And you don’t only not include things because you don’t think they’re great. Maybe you do think they’re great, but it might be impossible to reasonably excerpt in this context. There might be a million different reasons why someone ended up not being included. But it’s weird when you know a lot of the people, because it becomes a political thing.

There are even people who pressure you to select someone’s story. That’s definitely happened. Repeated [questions like] “Hey, hey, did you read it? It’s the best thing, isn’t it?” That was kind of weird. I tried to ignore all of that. And it’s not because I didn’t think the work wasn’t good, or the artist hadn’t improved tenfold and I was really impressed—it didn’t work in the book for whatever reason.

That implies that there was a rubric for what you included. Other considerations like being easy to excerpt aside, what were you looking for?

I was just looking for something that really interested me. In so many stories there will be flaws where it’s good, or you think it’s gonna be great, and then you start reading it and you get tripped up because there’s some interruption in the readability. Suddenly you can’t…the artist wasn’t really…they’re doing jump-cuts or something. Suddenly it’s too much of an effort to try to follow the story, because they weren’t thinking of the reader at that moment. You’re reading and reading, and if you have to read so many things those little fuckups will just make you stop and you won’t put it in the book.

Everything has to have a flow to it?

No, that’s not even what I mean. It could be really convoluted and everything else, but it’s at some point…How can I say this? I’m just trying to think of all the things that made me stop reading something. [Collins laughs.] I feel terrible saying this: I have fairly good eyesight, but sometimes you’ll get this minicomic, or even a regular-sized comic, and the writing will be so small, like the artist drew it big and they shrunk it down really little for whatever reason, and you can’t even fucking read it without a magnifying glass. After a while, because you have to read so much, you just get mad. But that’s another thing: I wouldn’t always get mad, I’d go get a magnifying glass. But what you choose has so much to do with your mood at the moment you’re reading something. How do you control that? There’s all these variables.

When I was reading and reviewing multiple comics every week, I always said “If I flip through this thing and I don’t like the art I’m not gonna read it.” I couldn’t read everything, and even if that ruled out some comics that I might have liked in the end, I needed to let myself off the hook in some way.

You have to do that. But I don’t usually abandon something just because I don’t like the art. So many times, if I sat down and read the whole story, the art starts to grow on me if the story is good. They really are inextricably intertwined.

I don’t like super-slick art. Like, I had never seen Geof Darrow’s work. I wasn’t aware of him, for whatever reason. And when I first looked at it, I said “Oh God, this is some superhero shit…but it’s a pig. Huh.” Then I started reading it, and I fucking loved it. I went and bought the whole series of those books, and I just loved it. It’s insane shit. It’s really professional-looking, and perfect, really, in many ways. Oftentimes that would just bore me, but in this case, once I started reading it, it was just so fascinating and beautiful that I fell in love with it.

You didn’t arrange the book by theme, which is interesting, and we’ll get back to it. But was there an overarching theme you were looking for when you envisioned the overall book?

I had initially thought that I would [have a theme], but then I realized that was a bit too manipulative of which stories would get in and which wouldn’t. I really like artwork from all different [kinds of comics]. I’m not stuck any particular style, or genre, or “team.” If I’d had to direct it that way, a lot of stories that I did choose wouldn’t have been chosen. I realized that late in the game.

I also started to feel like it pigeonholed the artists. If no one had ever read any of their work before, arranging them thematically would brand them as a [cartoonist] who does X—autobiography, or fantasy, or whatever the hell, political stuff. By not labelling things as fitting into a certain category, it liberated the stories, and even the artists.

When I gave up on arranging things thematically, I thought, “Well, I’ll just make sure that they read well, one after the other”—you know, what comes first, what comes second. I tried that, and again, even doing that, I tended to group things into certain types. Then I just said, “Oh, alphabetical,” and I think that works fine. I like it that way. What do you think? Would you have arranged it differently?

I don’t know, because I’ve never tackled a project like this exactly. But sometimes it helps to tie your own hands and allow happy accidents to do the work for you. You wind up making connections you wouldn’t have intuitively or consciously made; the parameters that you set for the project make them for you, and you can find out all kinds of interesting things that way.

That’s how I look at the book. By virtue of the fact that it’s in alphabetical order, you start with this Gabrielle Bell story that’s a very difficult read, emotionally. There are dead animals, animal abuse, and child abuse. It’s tough. If I were an editor trying to figure out what goes first, unless I was very consciously trying to set a tone—

You wouldn’t have that first.

Right. But this approach—“Well, the alphabet has forced my hand, so here’s what we’re leading with”—puts people in a headspace that you might not have consciously chosen to put them in, but which has interesting after-effects on how you interpret everything going forward.

It colors everything that follows it.

If there was a through-line for the book…Man, I don’t know, I was in a terrible headspace myself when I read it. I was having just a really…oof, quite a black day. I opened it to that story by Gabrielle and I was like, “Aw Jesus, I’m not gonna make it through this book.” But I did, and I enjoyed it. And maybe it was just my mindset at the time, but with one or two exceptions, I feel there’s a through-line of suffering, and how to endure it. Or not endure it, I suppose.

Yeah, I…go ahead.

At no point in Bill [Kartalopoulos]’s foreword or your introduction does it say, like, “And these stories are about suffering and trauma.” There’s just nothing. The comics are allowed to come to you without that filter.

Are you saying that you wish it had a trigger warning?

No, just that I like that there’s no advance notice about what kind of book it’s going to be. It lets you do the work for yourself.

Yeah. I’m flipping through as you’re talking and I realize that what you’re saying is probably true. There’s a lot of suffering in there. But to say that these works are about suffering or learning to deal with it and nothing else is really falling far short of the entirety of their meaning. Maybe I am attracted to stories of struggle, but if I look at all these stories, they’re capable of teaching us so much more.

I’ve kind of withdrawn. I’m trying to finish a book, and it’s taking me forever. When I read anything about my work that’s been written in the past, it’s often talked about in terms of victimization or abuse, when in my heart I feel like my work is about so much more. To me, so much of this stuff is funny. There’s a way out, and it’s often represented here in these stories.

Yeah. Gabrielle, just for example—her comics are very funny. Even when they are about troubling things, there’s just a deadpan sense of humor to the way her characters are drawn. They look lumpy, like they were molded from clay, and I’ve always really enjoyed that.

And it’s always really structured, with these six panels per page, all the same size. Kind of looks unfrightening, warm. Yeah.

That adds something that I don’t think you can pull out of the story or the dialogue. The style adds a new dimension to it. That’s the biggest truism about comics that I’ve ever said, and I apologize to anyone reading this, but it’s…true.

Right? But it’s basically written like a kid’s story. In a sense, it is a kid’s story. Which is not to say it was meant for children, but it’s a story of a child, told by a child. She’s not a child, but it seems like this story is very immediate.

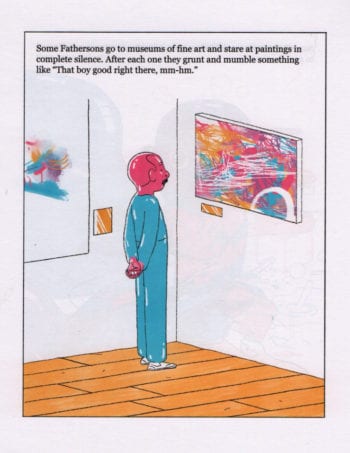

It reminds me of “Fatherson,” the Richie Pope comic you included. It’s similar in that it’s drawn in a friendly way, it has friendly colors, it’s about childlike behavior. I think a kid would like looking at it, based on the interests of my own children. But again, it’s not a kids’ comic. It’s just the way that it’s drawn that adds something to it.

It reminds me of “Fatherson,” the Richie Pope comic you included. It’s similar in that it’s drawn in a friendly way, it has friendly colors, it’s about childlike behavior. I think a kid would like looking at it, based on the interests of my own children. But again, it’s not a kids’ comic. It’s just the way that it’s drawn that adds something to it.

Right, but it’s so deep that it’s just so true.

Did you ever meet the Krayewskis, a father and a son? There’s this story by them called “Miss V (: My Last Love Story).” The father just died, but when I met them at SPX they gave me a stack of ten huge books. They were really trying to get people to notice this work. The father was writing it and the son was drawing pictures—or vice versa, I forget who was doing what, or how or why, or if they were doing it together. But the dad was from Poland, and he kept going, going, and going. Millions of stories. At that time it seemed like nobody was paying any attention to them, but they’re so prolific.

To a woman, their story is kind of depressing. But nevertheless, you understand this person who you feel is behind this story. I like stories like that, even if it kind of makes you feel uncomfortable, because [they give you] some understanding of what it is for this person to live in that way or what their internal or [external] environment is like.

And then Aaron Lange, the one who did the art school comics? He’s also done millions of comics, like so many. And yeah, I never heard of him. But I teach in an art school and [laughs] it reminded me of [that]. It’s really well drawn, beautifully drawn. It’s so mean, indifferent, and fed up with art.

What is the connection between the Krayewskis’ comic and Lange’s art-school comic?

I jumped from that one to the other one because they are both about men. Sometimes it’s like I don’t know what men are, and then I look at these things, and that’s what they are. [Laughter.] It’s funny. Look, I didn’t intellectualize any of this stuff. I just know that I had chosen those because it made me smile and I liked it. Is that enough? [Laughs.]

To get deep in the weeds a bit, when you’re selecting the best comics—

Okay, get rid of that word. Get rid of that word, because it’s not possible. OK, yeah, you’re choosing the “supposed best” or “so-called best comics,” right, yeah?

Mmhmm.

What is your responsibility to your readership? What do you think when you’re possessing them? Well, I don’t fucking know. [Collins laughs.] No, honestly! I’m not thinking I’m choosing the best because I know I am the filter. What matters to me is, Do I like it? Did I like it more than a number of other comics? If the answer is yes, maybe I’ll include it, because what else do I have?

It’s like grading student work, in that you’re looking for so many things. You’re looking for: Can they draw, can they write, is it working together? Then you think, Well, I’ve known this student for two years. Look at them two years ago and look at them now. God, they are so good, and they are so much better than they were. They’re really trying hard and they’re really actually finding out what they can do. They might not be your best student to someone looking in from the outside. But sometimes you get these students who are great coming in, but because they can draw so well they have no real way to push themselves. You can see that they’re stuck. Their stories are a little weaker. Any criticism you give them, they halfway don’t believe it, or get pissed because they know they’re good. And they are, but they get this attitude and they don’t really get better.

So on the outside you can say “That person deserves an A”—the person with all the talent—and the one who tries so hard and gets so much better and will continue to do so, from the outside you might think “That’s C work.” In reality, you’re looking at so many things that other people who might not be inside this classroom wouldn’t take into consideration.

It’s the same when you’re looking at all this work. Because we’re individuals, we tend to like certain things or be interested in certain things, not in others. You try hard to put that aside, but you can’t. You can’t get out of your own skin. In the end, you’re going to choose things you like for reasons you don’t even understand.

Are you asking me, Do I feel any responsibility towards the reader? Or if my role is, in a very dry and responsible sense, to present only the finest? I mean, what are you trying to ask?

Well, for example, a couple of years I was hired to write a piece on “The 33 Greatest Graphic Novels of All Time.” Immediately, I said to myself “This is going to be my list of the 33 greatest graphic novels of all time, not a survey of the major landmarks from each genre and tradition and geographical region. You can get that anywhere, but you can only get this from me.” How do you draw the distinction between the quote-unquote “best” and stuff that you, based on your own interests as a reader, as an artist, as a person, as a teacher, whatever, like the best?

This is different in that I wasn’t asked to choose my all-time best stories or favorite stories. It was just my favorites among those that were sent, submitted, or solicited at this particular period of time. In that sense, it is harder to impose your own tastes and preferences on the group. You didn’t direct yourself towards a certain group of comics, they’re just placed in front of you.

I went into it thinking—and Bill Kartalopoulos said—“It’s your favorite from this period.” He kept emphasizing, “You’re the one who’s choosing which ones will go in the book.” If we had been asked to honor the accepted greatest cartoonist or the best-selling up-and-comers, I mean, that would’ve been really different. Publicly that may have been more recognized as, this is good, this is bad, but it wasn’t like that at all. They always have a different guest editor because it’s understood that different tastes will be reflected depending on who’s judging the work.

Bill, in his foreword, says his task is different than the guest editors in that he’s seeing all the submissions and whittling them down to a broad range of suggestions, but one that’s still smaller than the overall submission group. As much as he stands by his personal taste and feels it’s informed and defensible, he puts it aside as he’s looking at work in genres or tones that he’s usually not interested in. He thinks to himself, Okay, well, this may not be my thing, but it’s a thing. Is it a really good example of that thing? Is it an ideal version of that thing? Is it doing something new with that thing?

Right, but he also admitted that he constantly chose things he thought I might like. I always thought, What exactly does that mean? I actually do like lots of things, so I wasn’t sure what he meant by that.

But with all those questions—is it doing something groundbreaking, is it really the best example of this type of thing in any particular year—even the most prolific artists aren’t vomiting up stuff at a fast clip relative to other forms of communication. What are the chances you’re actually going to get work that fulfills all those criteria? Sometimes, you’ll get really brilliant shining examples you can hold up and say No doubt, this is best, everyone will agree. Sometimes you’re getting a book that is better than others, but nevertheless this particular artist did a book that you liked far better two years ago. Yet you’re going to include this because it’s actually something you can say you admire more than you appreciated fifty other books that were also submitted. You’re not always going to get that many outstanding pieces of work, even from the best artist. If you look at a body of work you’re always going to have a preference for this period or this story or this book over another, even in one artist’s work. “Best” is a bullshit word. Nobody’s ever going to agree on it.

I feel like every time we talk we wind up in some weird semantic discussion, but I’m glad we’re not talking about whether or your stuff is autobiographical anymore. [Laughter.]

But don’t you agree with me? What you said before, about you choosing your favorite comics. When they asked for 33—why 33? Why 33?

I dunno. It’s a catchy number? Yours was number one, by the way.

Oh, really? [Laughs.]

Yeah.

Ok, well then, I agree with everything you said. [Laughter.] No, so, that’s the purest and honest way. You accepted that, and you interpreted your task as being to choose your favorite—the work that you thought was the best.

Right.

And so, in a sense, that’s pure. You can say, “It’s my best,” right?

Yeah.

And I think of everything I saw, I was trying to choose “my best,” to keep that kind of purity. I couldn’t take on the role of imagining what everyone else’s criteria would be, because they weren’t here in the room with me. If they had been, then maybe we could have talked about it, but they weren’t there! Where were they? I don’t know.

So, what did I miss? What should have been in that book?

I don’t know, Phoebe. In a weird way, getting together with Julia [as a couple with a blended family] made me read comics less, because I feel closer to it, and it’s harder to let go and enjoy things. I read what she does, and I’ll read things that friends of ours do, like Gabrielle and Simon Hanselmann and friends I follow on Twitter or Tumblr. But when we edited our book together in 2016, I felt like that was kind of my last word on the stuff I was interested in—with the exception of a couple artists that got away and we couldn’t include, like you for instance. Like, “This is basically what I like and want in comics, and I don’t really need to write anything about it anymore.”

Yeah. When I’m writing or working on something, it’s really hard for me, because when I’m teaching, all I’m doing is looking at other people’s work. You’re not talking about your own work, you’re not getting feedback on that, that’s kind of totally separate. You’re totally focused on the work of others. To do this book it was really more of that, in a sense—thinking about other people’s work. Doing that for long periods of time makes it harder to create. Never, when I’m working on a book [of my own], do I read a whole lot.

So maybe I’m the worst person to ask to edit this book, because I’ve never felt it was responsibility to stay on top of who is popular, and what styles are popular and good. Do you know what I’m saying? I don’t pay attention too much to fashions or trends, so if the guy at the Comics Journal is asking either of us to comment about that, it sounds like he’s not going to get an adequate answer. [Laughter.]

I told him that! But Tucker’s a very persuasive guy. He said I know your work really well, which is true—this is the third or fourth time I’ve interviewed you professionally—but I was still very nervous about it. Comics is a small pond, and I don’t want to screw up.

Well, that’s what I described, my anxiety in even editing this, because I did know so many of the people who had submitted stuff. It would be wrong to choose stuff because you knew people, right? So you try to avoid that, but there’s that kind of implied…I guess it’s totally invented, but you feel like you’re supposed to choose people you like personally. On the other hand, you know that’s bullshit.

Right. And while there was a time when most of the criticism I was writing was comics criticism, I’ve been focused on television for several years now, with music and movies and comics thrown in occasionally. In TV, with very rare exceptions, you never write expecting the people who work on the shows you’re reviewing to even see it, much less hang out with you over beers at a convention. I’ve gotten used to that. Comics feels much more intimate. It’s the question of, “Well, I don’t want to shit where I eat.”

It is. But I felt like I made honest choices and I didn’t show preference, and I read everything even if it wasn’t something that I imagined I would like just by looking at it. Looking at them all now, there are so many different styles, and you can see so many different influences on the work.

It’s funny: I did notice one thing, and I don’t even know if I included anything that would reflect this, but you know when people binge-watch? Obviously you must have this experience if you’re reviewing television, right?

Mmhmm.

You watch something and it’s not as compact as a movie. It goes on and on and on and on. You learn to either fall in love with all these characters, or hate them, or yawn when they come on, but it’s almost like there’s a certain rhythm that it has to have. Something exciting or disturbing has to happen in every episode, something has to be resolved, and then it happens again next week, or the next hour, depending on how you’re watching it. It’s like an open-ended world, like if you love it, you never want it to end.

I’ve seen that tendency in a lot of comics recently. There are stories with lots of characters—it could be a long book or a series of one-pagers involving in the same people—and you just have the feeling where it’s almost like a streaming miniseries. It’s borrowing from melodrama and General Hospital-type things even if it has monsters and…Am I making myself clear? Probably not. It’s like a different rhythm that I’ve seen. Like if you look at underground comics, you don’t see never-ending stories, or you don’t see that same kind of open-ended world-building that you could imagine will go on forever, and maybe does. I felt like this is the product of all these artists streaming things, so they’re kind of getting that under their skin, and it’s influencing other rhythms and patterns in their work. If I could think of any pattern that I’ve noticed, or any trend, it would be that.

And some of those books, I guess a lot of them, I didn’t include because…I don’t know why. It wasn’t necessarily because I didn’t like them, but because they were harder to excerpt unless you’re taking a really long piece, and there just wasn’t the room.

And some of those books, I guess a lot of them, I didn’t include because…I don’t know why. It wasn’t necessarily because I didn’t like them, but because they were harder to excerpt unless you’re taking a really long piece, and there just wasn’t the room.

Even Guy Delisle, Hostage—even that has such a strongly filmic quality. I mean, in a lot of the books the action isn’t really protracted, but in this particular scene it is. It’s like nothing happens, except he gets a piece of garlic. But I see people playing more with the time and speed. Sorry, I’m trying to say something deep, but I’m failing. Do you like them? Geof Darrow, did you like that piece?

Do I like Geof Darrow? Yeah, I like Geof Darrow.

So, have you known about him for a long time?

Yeah, because he did a book when I was a kid called Hard Boiled with Frank Miller. I had never seen anything like it at the time—that crazed level of background detail, and the weirdness of how he draws objects jutting out of everything. Everywhere you look there’s a syringe, or a scissor, or a Band-Aid, or a crumpled-up piece of paper, or something stuck to something else, everywhere. I got that book in high school, and I just kind of fell into it. It’s so absorbing.

Right.

He’s been a big influence in superhero comics since then. There’s a lot of people who draw like him. And he worked on The Matrix with the Wachowskis, so he had another career doing that kind of stuff. But I mean, I’ve always had a foot in that superhero world, so.

Right. Well, that’s good, because I had never heard of him. But it’s interesting that he did everything on these books, Shaolin Cowboy. He wrote them and drew them. Yeah. Yeah, I don’t know. It is what it is, man. [Laughter.] What can I say?

That’s pretty good. That should be the extent of the interview: “It is what it is, man.”

Yeah, it is. Oh, what did you think of the Julian Glander section?

I was going to bring that one up—that, and Julia Jacquette’s story about urban design through the lens of these sort of Brutalist playgrounds in the city. Those are the two stories that I thought bucked the trend of being about struggle and suffering. Julian Glander’s a pretty straightforward humor comic, and the Julia Jacquette comic is doing a slightly different project. It’s almost educational, you know?

Yeah, it is. And kind of beautiful. But the Julian Glander is so funny! I was just cracking up when I was reading it.

What was funny about it to you?

It was just so familiar. I had kids and we went through the whole Giga Pets, Mega Pets, then Beanie Babies, and Pokémon, then Webkinz—all this crap, you know? Children tend to be often obsessed with collecting all those whatnots. That continues into adulthood to different degrees. It’s just this whole idea of the value of things, and the value of experience, and experience that is virtual versus real experience. But really, they can both be experience, so who’s to say that one is less real than the other. I mean, virtual worlds can be so seductive, and can influence the way that you look at the world in general. I guess it just made me laugh because it made me start thinking about…I don’t know. I build all these little buildings right now for my work, and interiors, and I constantly feel like I’m making this other world, and it’s not a virtual world in kind of the 3D-animation digital sense, but it’s a virtual world in that it didn’t exist before I started building it, and it’s constantly changing. Half the time I feel crazy, because I feel like I actually live in this little world. Me being me, it just…In showing you this stuff, it brings you out of it for a moment, and it just makes you laugh. I don’t know. Maybe it’s a nervous laughter. Who knows?

I’m glad you brought up your own world that you’re constructing, because that’s what I thought of with both Julian Glander’s and Julia Jacquette’s comics. The Glander one has this 3-D modeling aspect to it, and the one about the playgrounds is literally about creating spaces in which people can move and play and do things. I was like, “These feel connected to what Phoebe’s been doing, at least on an aesthetic level—in a unique way, relative to a lot of the other work in the book.” It was interesting to hear you had a connection to it yourself.

I hadn’t even thought of it before, but definitely.

Was there stuff that you were surprised you didn’t see more of, or more than you expected?

Everyone has been surprised by Emil Ferris.

Yes.

I think they have. Someone said to me, “You didn’t choose an excerpt that showed her best drawing,” which startled me. When I chose the excerpt, I was trying to find something that could be contained in a certain number of pages. Maybe I didn’t choose [well]…I don’t know if I did or not. I was definitely surprised when I first saw her work. You look at the drawings and you experience drawing those pictures by looking at them. Each line, your eye traces it. You imagine doing it, the amount of time and concentration it takes. At times, you wonder where she began on a page, and where she ended, and what was planned. I’m looking at a page now, and—you have the book in front of you?

Yes, I do.

Yes, I do.

OK. I think it’s the third page. Well, the second page of the story arc, page 93, I guess it would be. Do you see the rabbit with the wing? She’s outlined the wing. The wing in the front is outlined with a kind of sketchy line. But, then, the farther-away wing, it’s defined by a line until it gets to the hair. And then, the line goes away, and it’s totally drawn up in negative space, and the hair. And it’s really weird, because it almost looks like the hair is cut out, but you know it’s the wing. I don’t know if she does that in other places, but I find myself looking at the drawings, and thinking about the process. They make you think about process, for some reason. They make you stare at them in that way. At least me. Which I found really interesting. So, it surprised me.

This is a pretty basic statement, but it’s true with almost everybody who gets to guest-edit the book: As an artist, you’re going to notice things that the non-artists among us don’t.

Yeah. Probably.

I don’t know that I would have caught on to the hair thing that you did. But it made such an impression on you.

Yeah. Some drawings are very finished, like the face. The hand is just an outline with some quick shading on it. You almost feel her thinking, and her preference for certain areas. It’s all there. There’s nothing hidden about the process of drawing it. If you look at Jaime Hernandez, it’s really perfectly drawn and everything, but you don’t get a sense of process there.

No.

And not because it’s pure black and white, and not pencil. It feels—

The hand is invisible in his work.

Exactly.

In 2001, Alvin Buenaventura had a gallery show in San Diego, during the Comic-Con. You had work in it; I think the catalog actually came with pieces of your garbage, if I recall correctly. That was the first time I had seen anyone’s pages outside of a book. For some artists the finished product looks so clean, like it emerged fully formed from the brow of Zeus, and Jaime’s one of them. I remember, for certain artists, just seeing Wite-Out on an original page was shocking—like, Oh my gosh, it’s Wite-Out!

Right. With Emil, you’re not seeing Wite-Out, but you feel like you can read her process in her drawings. You can feel it, almost. It’s very tactile. I wouldn’t say that I need to feel that, but when I do it’s arresting. I mean, I love Love and Rockets, I don’t care that it looks so perfect that it’s almost blinding. I still can sink into it.

I’ve actually been wondering what comics you’re into. Usually when I’ve heard you talk about other comics or other cartoonists, it’s been in the context of the stuff you read when you were a kid, people that you knew in San Francisco, people you corresponded with or who were otherwise responsible for getting you into comics in the first place when you were a teenager. After that, I drew a blank. I was like, “Who has Phoebe read after she was 15 years old?”

I read lots of things. I guess you pointed out that you see [a theme to] what I’ve chosen here, but it’s not conscious. I have a pretty big collection of romance comics. I always loved Little Lotta and Moochie Mooch and things like that, but I’m not like a collector fan—I just like to read it. I have hundreds of photo-romances, Italian and French; I love reading them. Now they are disappearing too. I mean, people send me stuff, and I read a lot of them when I can…What do I like? If you’re talking about superheroes, the only one I ever liked was called The Man-Thing. Not the Swamp Thing, The Man-Thing, the one who sucked up peoples’ emotions. When I was a teenager I bought all of those. I’ve never talked about that.

No, I’ve never heard you say that.

Yeah, but I still have a bunch of them and I think they are fucking fantastic. I love Japanese horror.

I think comics, in a way, have frustrated me to a certain extent, partially because I like words. Comics are read very quickly, they are consumed very quickly, and they are made very slowly, so I always feel this frustration when I’m working. Which is why, I guess, that in The Diary of a Teenage Girl there is so much prose and text, and then you just get into that rhythm. I always wonder about that. Like, does that mean I’m not really a cartoonist? I don’t know, maybe. I mean, what the fuck is a cartoonist, right?

[Laughs] Are you asking?

[Laughter.] I don’t know. I don’t know if there’s an answer. [Sigh.]

I tend to be an inclusionist with almost everything, so I’m willing to—

Yeah, me too, anything’s a comic. [Laughs.] Okay, so I don’t know. I don’t know what I like.

I just made my students watch one of the SpongeBob episodes called “Doodlebob” or “Frankendoodle”—something like that, and it’s almost painful to watch. It’s about being an artist. Something suddenly reminded me of it when I was in class the other day, so I said “I’ve got to show you this SpongeBob episode.” I mentioned which one it was, and there were two students who were like, “I can’t watch it, it gives me so much anxiety. Can I please leave the room?” [Laughter.] it’s this episode where there’s a real person on the ocean in a little rowboat. It’s an artist, with a little artist smock on, and he’s got a pencil. He’s trying to draw, but his pencil drops into the ocean and he can’t catch it. The pencil gets down to the bottom of ocean, to Bikini Bottom, and of course SpongeBob gets it and starts drawing, and the drawings start coming alive. They are alive, and they are angry. The drawings are aggressive and start doing bad things, and it’s just like…It lights up in you every theory you’ve had about, “if I draw this am I going to get into trouble? If I do this, what is it going to affect?” It surprised me, and actually makes me happy, that some of my students were just so viscerally responsive. They had the same reaction I did. All this self-conscious shit that sometimes makes you fear your own hands.