(For Part I of Amy Poodle's article, click here)

MAPPING THE NEGATIVE ZONE

King Mob and the rest are ghosts.

Dane is pierced by the blank badge and killed.

Let me show you how.

Ever since he was a little kid, Dane's been haunted. We meet this spirit just after John and Stu make their way off along the river - a spindly, hunched mass of black icicles Jack Frost appears to Dane and proclaims the death of both men. Dane's 'Fuck off, you' in response suggests a longstanding relationship, but it's not until issue three that Tom o’ Bedlam, his initiator into invisibledom, gets to the heart of it. Jack Frost was the threat Dane's Mother terrorised him with when he was naughty, in lieu of having an actual Father around.

'And you still see Jack Frost, do you? He still comes round when you're bad, does he? He must come 'round a lot then.... He's a bit scary, is he? But he looks after you, eh? It's worth being a little scared of him because he makes you feel tough when there's trouble. He makes you feel hate instead of uncertainty and fear.'

Jack Frost is the bad-father, the empty father, the vacuum frozen up. He's the absence of love making Dane so restless and angry. And later on in the scene, this is what Tom brutally attacks, assaulting Dane's emotional armour by physically attacking him, by threatening to touch him the way his dad didn't. He forces Dane to stop projecting his pain as a demon Out There and accept the absence as part of himself. He makes the darkness visible, forcing it into awareness. And so the negative space around Dane McGowan opens its eyes and blinks, and the boy sculpted by his parents' unhappiness (who in turn were sculpted by their parents' unhappiness, and so on, successive generations of unfulfilled lives sculpted by poverty) is sloughed like a dead husk. By becoming cognizant of and processing his pain, Dane becomes free, amorphous and invisible.

Jack's story parallels those of the rest of his cell. Those whose origins we're made aware of, at least. Lord Fanny, the cell's resident transvestite shaman takes hir magickal name from Tlazolteotl, 'the Eater of Dung, Goddess of Lust and Shame', hir patron. And it's this identification with and awareness of the demonic energies presiding over hir former life as a prostitute, the patriarchal power structures that transformed hir from person to product, which affords hir the same freedom Jack enjoys. In short, ze reclaims the role ze's been forced into and transforms a weakness into a strength, a dirty joke dedicated to her God. Hilde, hir former self, sacrificed to Lord Fanny. Likewise Jim Crow is the negative space around racial oppression, King Mob around the idea of the revolutionary and Ragged Robin around the sex interest. At one point in volume two Morrison actually forces the characters to perform auto-critique, exposing the negative ideas informing each of them. The characters are stereotypes, but they're stereotypes in possession of themselves, aware of their chains and pregnant with the possibility of transcendence.

Each Invisible, then, is the ghost of an original text, the anti-being in the margins of their previous representation. This is who they become when they wave goodbye to the chronically reflexive slave self they were, their magickal name its headstone.

This intangibility doesn't end there, however, it's a theme returned to again and again. Many of the characters are locked into multiple cover stories, losing track of their original Self in the process, King Mob's cell members rotate elemental roles between adventures and 'ultimate Invisible', Mr. Six, beats King Mob's performance in Room 101 hands down, discarding and acquiring personalities depending on when the mood takes him. But it's the Supercontext, the 21st century alternative to selfhood, which best articulates this quality.

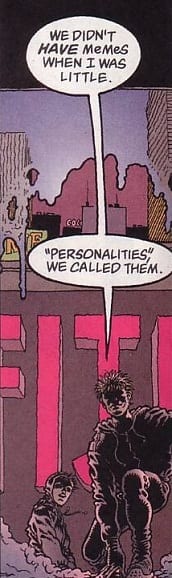

Being as it's the logical conclusion of themes already strongly present in the comic, it makes sense that we're only introduced to the Supercontext in the comic's final issue, but Grant gives us plenty to go on. The Supercontext circumvents the book's up until this point primary dialectic by suggesting that all conflict derives from an insistence on an illusory self, and in action manifests as the MeMeplex, or, as future invisible Reynard puts it, Multiple Personality Disorder as lifestyle option.' This idea's not new to Morrison, it's been present in his work since his 21st century schizoid Joker in Arkham Asylum, but Grant more thoroughly argues his point here. I'll let Dane and Reynard do the talking:

Reynard later goes on to describe her own initiation into invisibledom, an initiation which entailed total identification with a lifestyle as antithetical to the Invisibles' own as it's possible to get: she became an accounts manager. All of this in an attempt to dissolve her own 'existential alienation dilemma in unity'. The comic's focus on exploding the boundaries between This and That deeply disrupts traditional notions of Being, assuming you'll forgive the conflation of the term with identity. Upon its transformation into the MeMeplex, the stable narrative of selfhood disintegrates into the dynamic interplay of occasionally conflicting, co-operating, or indifferent micro-narratives, losing all solidity, in a condition of permanent revolution.

Seeing as it directly reflects this restless, churning approach to character, it's probably worth probing deeper into the Invisibles' mise en scene here. In part one of this piece I talked about the way the comic's shifting scenery articulates the mediated sludginess of early 21st century postmodernity and its inevitable collapse into the hypermoment, both of which I'll return to later, but right now I want to go way back to the beginning and expand on the stuff that inspired all this. It began with that pig mask hanging inside the window of Alan Dunn's House of Fun: the fake shop-front acting as a disguise for the Outer Church's east London interrogation centre in volume one's closing story arcs, Entropy in the UK and House of Fun. It was the way it resonated with so much of the iconography of my childhood and late seventies' British pop culture, particularly the spooky kind.... Here, take another look.

There's the Wicker Man in there, there's the monstrous shop owners and landladies crouched behind a beaded curtain straight out of Roald Dahl's Tales of the Unexpected, there's even the old Jokes and Trick's toy cards, and not only that but there's the overriding abjectness of British vanity shop culture, an energy which, although not entirely vanished in the present day (for proof you need only check out the weird, abandoned RACEWAY: Racing on Giant Scalextric's Sets ...err.. 'shop' across the road from my flat), has dissipated in the thirty odd years and become doubly creepy in the process. This is an image which is not only haunted by the very real threat, in story terms, posed by the Outer Church, but by our memories of prior ghostlinesses also. Because of this, it's not simply an exercise in nostalgia, but in dyschronia. The feeling that time is out of joint is one of the key features of a haunting, a feeling the undying spookiness of the referents here feed directly into. Because the figure wearing the animal head mask is still waiting at the newsagent's window, the shopkeeper still crouched behind that curtain, the face on the Joke and Tricks' cards still leering out of some imaginary turnstile of the mind. But as I said in part one, if this was the only hauntological feature of the terrain the two armies war for then it would hardly be worth mentioning - however it isn't. In the story arcs featuring the House of Fun alone there's Dr Who monsters and stage sets, the acid laced sci-fi of late seventies' zine and comic culture in the form of Gideon Stargrave, the eternal horror of Orwell's cobwebbed but ever felt torture chamber, Room 101... And it's not just British hauntologies referenced, but in the second volume American ones too.

Hauntology isn't big in the U.S.A, probably because it's an esoteric subject and its recent resurgence has largely been limited to blogs with a distinctly British bent, however that's not to say America doesn't have any skeletons in its closet. Volume two arrives with a blast of James Bond and Man from Uncle military bases, Whitley Streiber style alien abduction and Roswell UFOs. What fascinates about this particular hauntological strand, is the way in typical American fashion it materialises the immaterial Other. As I said in part one, just because these entities come from Mars and not the Spirit World, or from underground as opposed to the Underworld, they still perform the same function as their British counterparts. The secret government is still plotting against us, the aliens may still come to steal time from us at bedtime and the UFO still sits beneath the desert, waiting. Dissections happen as we speak. All of this in an eternal sideways realm outside of conventional history, through which brittle partition the flying saucers may burst through, lasers firing, at any moment. Or as a tranced out Fanny tells it, complete with Hollywood special effects...

'In the endless, floodlit cells of the Reverse Universe, the armies of the Outer Church are gathering in their millions. Stealth armour continually scanning for and imitating human nightmares, waiting for the order to come and for it to begin at last... the Invasion. The Armageddon.'

Just as the comic's British mise-en-scene doubles this effect by referencing not just spooky themes but half-forgotten, half seen texts with spooky themes, so does the American. I could give endless examples of the kind of thing I mean, but there's really not enough space and I'm sure you get the idea by now. Anyway, what really interests me here is the meta-narrative serving as the bonding agent for this torrent of competing hauntological narratives, Conspiracy Theory. Conspiracy Theory, with its basic Us vs Them dynamic is often hauntological. It suggests that there's our world Over Here and then there's the Other World, where shadowy powers, whether or not that's the Illuminati, the Space Brothers, Cthulhu or the blind teleological currents of McKenna's Timewave Zero, conspire eternally to overturn our own. Not just in a physical sense, by colonising, but in a psychic sense too, making a nonsense of our past, our futures and our place in the universe - our very sense of being. Talk about spooky visitations collapsing history! Conspiracy Theory is also ghostly in another sense: the way it dates. Front loaded into most conspiracy narratives is the idea that at the appointed hour the plot will bear fruit and the conspirators' hand show itself. But, as we all know, in reality this is generally never the case. Ultimately the year 2000 did not see a global computer crash empty the silos of the world's nuclear powers and the New World Order never arrives on schedule, and while this might be a problem for the people who've invested themselves in these non-events, in the Invisibles it only strengthens the transparency of its landscape. Retro futures, futures that never happened, are big in hauntology. Vanished utopias and dystopias haunting our present remind us of a time before History ended, and Grant Morrison races through them panel by panel, just as our present day online culture channel surfs them at light speed, everything available so rubbishable, disposable, making history of the ends of history. This dreamy comic is musty with the dust of decomposed iconographies and we cannot find purchase because it's moving too fast and if for a split second we think we do, our foothold collapses into nothingness almost instantaneously. There's nothing solid here.

And being a ghost world, it trails soul stuff in its wake.

Whenever the magic is really flowing and the boundary wall of the Space-time Supersphere the Invisibles inhabit is reached, this slimy sci-fi gunk appears condensing on its surface. It comes in two different varieties, Magic Mirror and Anti-Mirror, but, amusingly, Mr Six and his friend's in the P.I.S (the Paranormal Investigations Squad) refer to it simply as 'ectoplasm'. And just like the ectolasm conjured in the famous spirit photographs of the early twentieth century, across its swirling surfaces we can discern the faces of the dead, from the dinosaurs to Shakespeare. Of course it arrives with a typically credulity busting explanation in tow.

'Try to understand this impossible 'It' as an Angel, a God fallen into the world it had created. An artist trapped in its own masterpiece.'

Everything, basically, trapped inside everything. And everyone, the goodies and the baddies, want to get their hands on it. Which makes sense because it's one of the core mysteries in the comic - it describes ultimate reality. It goes without saying that when you get right down to it, the fundamental stuff of the Invisible Universe should be a superfluid, reflecting all of 'space-time', all texts, across its surface, because that's what I've been describing for the vast part of this essay. It's just a further subtraction, another negation, atop another negation, etc., right down to the purest symbol of ghostliness it's possible to arrive at. It relects our present day information culture back at itself. On the surface of the mirror every story that's ever been told is immediately available, with one narrative flowing seamlessly into another, the distance between each bridged by thought. This is a poetic description of the world we scry via our laptops and I-phones, our online world, our 'information age' and Grant knows it. But for him and the Invisibles, the mirror isn't a direct route straight to nostalgia, as it is for so many of us, but a portal to revolt.

This is the topography of the Negative Zone, its landmass and unhabitants. .

I promised you a map, didn't I? Well here it is.

Here the map is the territory.

The only common features we've been able to find in this place are dispersion, revolution and a corresponding rupturing of the rules of time, space and being. And this is what the ghost comes to deliver. I believe Derrida makes much of the fact that in Hamlet the message of the the King's ghost, the message which kickstarts the action, is conveyed as much by its presence as by its gloomy utterances. In the end the raw fact of its being there tells Hamlet all he knows about Denmark being out of joint: his family's unquiet history stalking the battlements is in and of itself an omen. The ghost, then, is the act of rupturing incarnate, the medium and the massage both, and this is the only function it can perform, able to speak only in terms of condemnation, able to express via its wails and shrieks only discontentment with the current state of things. This schematic is exactly the same in the Invisibles. One of the many esoteric maxims the Invisibles makes much of is the hermeticist's famous 'As Above, so Below', and I think by this point it's clear that the Invisibles are, if you like, the 'voice' of the disruptive world their war plays out on. They are, as I said in part one of this piece, the revolutionary thought that occurs when time and the world are put out of joint, an emergent property of the mise-en-scene, reflecting all its characteristics. And made flesh, this world, now able to convey itself, naturally does so - as a function of its fundamental disruptive impulse does so - the characters able to move freely in time and space, conduits of disruption, bearing the flag, the map, of their territory as a blank badge pinned above their hearts. Or to their hands.

I did mention the Invisibles travel in time, didn't I?

As anyone who’s read The Invisibles knows, time travel is one of the story's key features. We begin with Tom and Dane's blue mould enhanced Situationist style derive through London, reclaiming physical space, and quickly move on to the second arc where time itself is detourned. This is the difference between the invisible revolution and its physical counterpart. The latter is confined to an exact location on the map and a specific moment, whereas the former will intrude anywhen, whenever the revolutionary thought occurs, in whatever form. And so the Invisibles' time jaunts takes in the sights of of Revolutionary Paris, the 1920's with its death knell for the aristocracy and the hyper-sci-fi end of history itself in 2012. It's interesting to take a look at the specifics of each mission, as well as the form the time travel takes. For much of the book's duration, the Invisibles are only able to travel in time via a technique Morrison dug out of the bizarrely named Gnostic Voudoun Workbook, a technique which employs a kind of astral projection. In short they manifest at their destination as ghosts. Hauntologists obsesses over signifiers like crackle, hiss, decay and degradation and they characteristically picture the haunting as moving forward in time, objects from the past emerging in a future where they cannot belong, but The Invisibles is happy to break this rule. I have no problem with this. If the 'goal' of the haunting is dyschronia, then it matters little whether or not the dyschronia is the result of the object moving forwards, backwards on sideways in history. All that matters is that the flow of events is shattered and correspondingly stable narratives, stable selves, and the unbroken sense of Being is broken down. But doesn't whatever direction across the space-time Supersphere you're talking about have to be a real direction, somewhere we've actually been, for rupture to occur? Well, hmmm, I think it's fair to say that most of us haven't been to Hamlet's Denmark. But, whatever, I'll go deeper into this in part three. For now, though, all we have to do is drink up the strangeness and put ourselves in the shoes of the Invisibles whom King Mob and the crew visit themselves upon to get an approximation of the hauntological effect. Back to the missions.....

In their first two missions, then, the Invisibles are constrained in terms of what they're able to do. Happily for hauntology traditionalists, in revolutionary Paris they're tasked with plucking the Marquis de Sade from his 'square' on the chessboard of history and depositing him in 1994. While on the surface of it the Marquis and Derrida's famous Spectre of Marx share little in common, the two both perform a revolutionary function. The Marquis is employed by the Secret Chiefs of the Invisible Order to chart new sexual frontiers, and, although he doesn't represent revolt in a physical sense, his 'intrepid new breed of men and women' haunting the mansion at La Coste where he makes his base conclusively overthrow traditional notions of the Way Things Are. We only get a snap shot of their 'work' but de Sade's brave young perverts are seen in the space of one short issue reclaiming their physicality by public farting and shitting, disrupting the dominant ocularity of a culture obsessed with distinctions by surrendering their sight to the all pervading sensuality of blind sex in floatation tanks, sublimating their trauma via contact with the 'bad' ectoplasm, anti-mirror, and, in the form of La Coste's pervert elite, the Nons, jettisoning gender itself. The Nons are particularly relevant in terms of this discussion because they embody Queer Theory, with its perpetually deconstructive approach to sex, gender, self and the power dynamics we've slathered on top of them. Like the Invisibles, they have no stable core of selfhood, but fluctuate according to whim or necessity, whatever they appear to be on the surface haunted by the possibility of another, negative, reading. A ghost text which may manifest at any moment....

And all of this, this ultimate kingdom of the flesh, presided over by the spectre of the super-libertine.

The Invisibles' second act of time travel also embodies deeply spooky themes. The 1920s with its backdrop of dreamy opium dens, political instability and spiritualism provides a perfect backdrop for all things hauntological, and King Mob, the only member of his cell to make the journey there, gets a mouthful. Mob's mission centres around the Hand of Glory, a powerful magickal artefact his cell have obtained in the present but to whom its operations and functions are still a mystery. Not so, though, to Billy Chang, the 1920's team's expert on the Occult. And so Mob travels back to 1924 to learn how Chang gets it to work. Chang's cell members, King Mob's anarchist predecessor, King Mob, his lover and consort, Queen Mab, along with the libertines Lady Manning and her cousin, the young Tom o' Bedlam, activate the Hand twice in all. The specifics of each activation aren't important, although in predictably spooky fashion the culminating rituals bear a close similarity to that mainstay of spiritualist culture, the seance, but instead of calling down the spirits of the dead, the team contact 'time spirits'. The Hand of Glory is described in folklore as the consecrated hand of a thief or murderer and it performs the function of turning its user invisible, but, as we have seen, invisibility in The Invisibles is symbolic of a ghostly, time-dislodged state, and the Hand of the comic is a tool to operate in this sphere. Morrison, employing the comic's frequently occurring game metaphor, at one point has Jack describe the Hand as a 'cursor' which moves around in time, opening windows (pun intended) into the future and the past. Obviously, then, things go pretty badly for our 'little band of anarchists'. The first operation of the Hand unsticks time, so that after its completion the Invisibles arrive slap bang in the next day, the temporal elipsis never explained, and leads to a lovely sequence which sees King Mob and his 1920s counterpart slack-jawed in the middle of a timequake, the city around them boiling up with dyschronisms: a 1920's ford becomes a modern sports-car, the sky is suddenly crowded out with skyscrapers and passenger planes. From a hauntological point of view its enjoyable to watch the first King Mob, a dyed in the wool Marxist materialist from before the End of History, freaking out over the results of their magickal time meddling. 'Forget Whitehall. We could blow up reality', his ancestor explains. Later, things get worse, as Tom, unable to cope with this state of being in 'so many places at once', uses the hand to minimise time itself, collapsing the world into a point, catapulting his team mates wildly across the supersphere and eventually returning the present day King Mob via a circuitous route through his own memories of the past and future, back to his home time. As the book goes on its interesting to note there's a steady progression from the 'solid state thought-forms', the living thoughts, the Invisibles become in order to travel through time at the beginning to physical time travel - a slow and steady concretization of the idea of non-local revolution. Because purring away in the background to all this is one of the book's major subplots, a subplot which reaches its culmination at the end of volume two and the completion of the world's first time machine.

Created by future Invisible Takashi and test piloted by Ragged Robin, the time machine represents the point at which time travel not only becomes a literal fact, but also freely available to humanity at large. It presages the dawning of the civilization Mason Lang, the time-project's bankroller, envisages midway through volume three.

'What would they look like if they could move through time and space at will? Would we know them if we saw them?'

The whole idea being that if we could move as freely in time as we do in space, then we'd be here already, all of history a soil cultivated by our Omega Level future selves, ending in their own germination. So the time machine really equals the end of progress within three dimensions - the final point of revolution. It promises the absolute nonsensing of linear time, a jumping off the game board. And in the end even it is revealed to be a flimsy first intimation of our future reality. Like the rocket-ship before it, a tin can which will inevitably prove to be absolutely useless for deep space travel, it must eventually be discarded in favour of other, safer, more appropriate means. In the Invisibles this final stage is represented by the Harlequinade and their Outer Churchian iteration the King in Yellow and his dwarves, both of whom represent the last stage in human development, our dissolution into magic matter itself, making their home permanently outside time, the time machine only the key which unlocks this door. If the Invisibles' first time travel adventure was about dislodging specific entities in time, then the second is about dislodging time itself and the third doing away with the concept altogether.

We all become invisible.

'Initiation never ends.' Mantra of the Invisibles

Although the apocalypse it prophesies and progresses towards, ostensibly, for the purposes of telling a story, inhabits a specific point in the map-grid of reality, December the 22nd, 2012, at that point the calendar stops and notions of prophecy and progress are torpedoed altogether. However, this isn't simply an articulation of the existential ennui we all experience in postmodern, western society - no, as I've said before its the mise-en-scene, the eternally collapsing hypertext, which articulates that – but of the moment of permanent disruption this resolves itself into. Morrison expresses this idea in many ways in Glitterdammerung the comic's final issue. To begin with there's the fact that it occurs after the story has arrived at its conclusion. In the previous story arc the Outer Church and the Invisible College have been shown to be one and the same and so the war is to all intents and purposes over, everything subsumed by total reality, and issue 2 (or 11, depending on how you view the topsy turvy numbering Vertigo went for) is full-stopped by a conclusive: THE END. But unlike the total reality of Francis Fukuyama's End of History, unending capitalism, there's a coda which shows what happens 'beyond' this point. Because it takes place outside of the confines of the actual story, issue one, like the King's ghost, transmits its message of chronological disruption via both form and content. It exists in a space which is neither yesterday or tomorrow, so immanent - always happening. This meta-disruption which occurs everywhere at every point, this hole in everything, is reinforced further by the steady disintegration of the comic's panels as the issue progresses, cigarette burns eating away at the text, until we're left with the final iconic image of a blown up full-stop on a white field, the Ur Hole if you like. When all is said and done, this is perhaps the most elegant expression of the hauntological ideal - not a ghost or ghoul, but a pure representation of the collapse itself. The absence that is a presence.

Forever bored into the mind of the reader who, at the time of publication, had invested six or so years in arriving at that final 'panel'.

By locating the apocalyptical final issue outside time, The Invisibles states that the world is always haunted by a ghost of itself, at every point pregnant with its own overthrowing. This is, of course, the fundamental feature of the magic mirror: it is holographic. Every moment contains every other moment, all possibility inhabiting the same space. The text fucked and fucking itself. The Invisibles message is of always latent possibility, rereading and reinterpretation, and its unstable, uncanny atmosphere and labyrinthine, self-reflexive, recursive structure makes this feeling almost impossible to shake off, its readers often leaving the text with a new attitude which naturally resists the reality we daily inhabit.

'But surely it's just a comic book!' you say.

We’ll see about that.

Coda: when I reached the final leg of this piece, the ‘victory lap’ as my fellow Mindless One, The Beast Must Die, would say, I thought I’d check out some music a mate had sent me via Facebook. The opening sample ran thusly:

‘Seven is both there and not there, same as nine eleven. So these numbers, one through twelve, all have their own role and function. Nobody invented numbers. They came simultaneously with the creation of the universe.’

But, blah, It wasn’t very good, a bit sub Orb circa 1990, so I stuck on some Kashif instead.

Join me, won’t you, for part three of this essay. Magic mushrooms, flying saucers, the Great Old Ones and magic numbers await.