The twelfth and final issue of Alan Moore and Jacen Burrows's Providence came out in April 2017, over six months ago. Even though I think about the series frequently, I can’t come up with a single, comprehensive thesis that does justice to Providence. One point about Providence that I can tentatively argue, however, is this: the climax of the book is Moore’s meta-meditation on the shape and nature of his comics career, written as he prepares to leave the medium.

Spoilers, etc. And a shout-out to Facts in the Case of Alan Moore's Providence, the comprehensive annotation website helmed by Joe Linton, Robert Derie, and Alexx Kay. (When I read and write about Providence, I keep one browser tab open on Facts.)

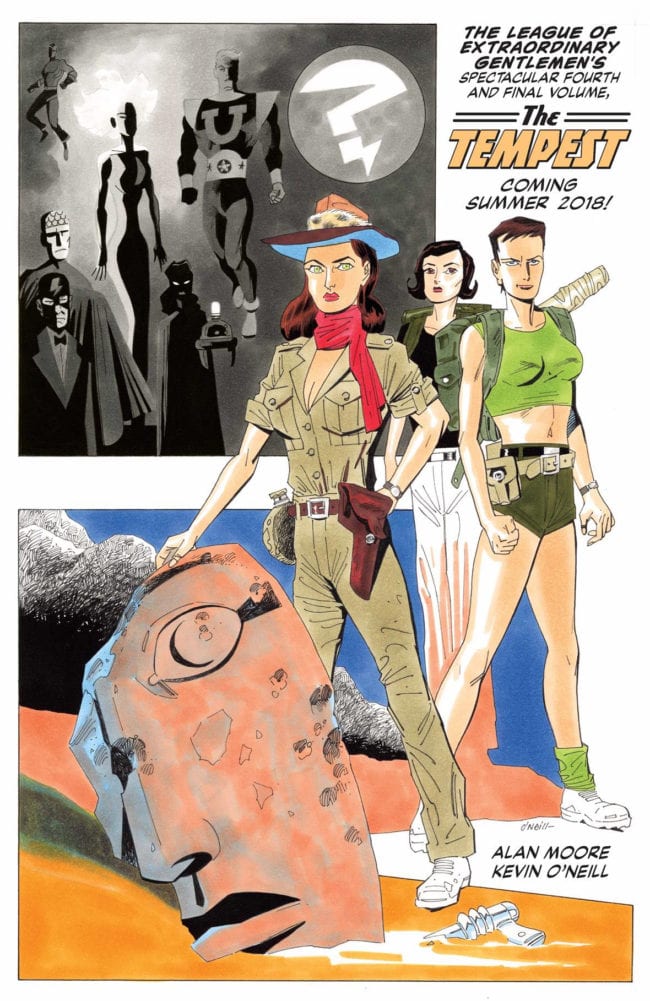

The Tempest

Moore has been leaving comics for a long time. In an interview with Jon B. Cooke in Comic Book Artist #25 (2003), Moore discussed his plans to bring his America’s Best Comics line to an apocalyptic finish in late 2003 (although he left open the possibility of publishing future League of Extraordinary Gentlemen books through ABC/DC). After years of grueling deadlines, Moore wanted to move into more personal and less predictable art-making:

I’m reaching a point in my life where what I want is less security, less certainty. I don’t want to know what I’m doing in a month’s time, or at least I won’t do after this November or thereabouts. I might write another novel. I might write a grimoire. I might waste a lot of time getting back into drawing, doing some more pictures. I might want to do more performances and release more CDs. I might want to write a play. I might want to get into sculpture. I might want to do a lot of things that are not going to obviously have any commercial value, which people might not like. I want to have that freedom. (55)

Luckily, his retirement from comics hasn’t stuck: he’s written plenty since shutting down ABC, including two League adventures for Top Shelf/Knockabout (Century [2009-12], and the Janni Nemo trilogy [2013-15]) and various projects for Avatar (the Providence prequel/sequel Neonomicon [2010-2011], the first six issues of Crossed Plus One Hundred [2014-15], and of course Providence). It’s true, though, that most of Moore’s effort in the last decade has been devoted to non-comics projects like his counter-culture magazine Dodgem Logic (2010-11) and his massive novel Jerusalem (2016). Meanwhile, his disdain for American mainstream comics and the superhero genre has escalated, due undoubtedly to how DC has wrung every cent out of the Moore comics they own while trying to undermine the legacy of Watchmen with irrelevant prequels and integration into “continuity.”

In September 2016, during an interview with the UK newspaper The Guardian, Moore laid out the schedule for the rest of his comics career, noting that he had “about 250 pages of comics” left to write, including the final issues of Providence, his suite of Cinema Purgatorio short stories with Kevin O’Neill, and a final League book with O’Neill: “After that, although I may do the odd little comics piece at some point in the future, I am pretty much done with comics.”

Moore’s plans to leave comics have shaped the stories he tells, especially in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. In Black Dossier and Century, Moore includes the wizard Prospero (from William Shakespeare’s final play The Tempest, 1610-11) as the ruler of a fantasy realm called the Blazing World, a land similar to Moore’s notion of “Ideaspace,” a universal repository of characters, icons and belief systems that can be accessed by individual seekers through magic and deep thought. But Prospero and Moore share more than Platonic beliefs in imagination: artist Kevin O’Neill draws Prospero to look exactly like Moore in 3-D glasses. Moore and his impending retirement thus share the autumnal vibe of The Tempest.

The comparisons thicken in a recent Top Shelf press release for the final Gentlemen tale—itself called The Tempest—due in 2018, where Moore and O’Neill promise both a visit to the “Jacobean antiquity of Prospero’s Men” and a commentary on their love for the comics medium and current dissatisfaction with the business of comics:

The world’s most accomplished and bad-tempered artist-writer team will use their most stylistically adventurous outing yet to display the glories of the medium they are leaving; to demonstrate the excitement that attracted them to the field in the first place; and to analyse, critically and entertainingly, the reasons for their departure.

It takes hubris, or at least a cheeky sense of humor, to compare yourself to Shakespeare, but Moore makes his point: his Tempest will be his last comic, just as The Tempest was Shakespeare’s last play, though I personally wouldn’t object if Moore flipped in and out of retirement like Hayao Miyazaki.

A Momentous Encounter

Moore’s imminent retirement also influences his scripts for Providence. The series divides into two halves, with the first six issues presenting Robert Black’s encounters with Lovecraftian characters (Dr. Alvarez, Dr. Hector North, Shadrach Annesley, Etienne Roulet) who use the occult secrets found in Hali’s Book of the Wisdom of the Stars, Moore’s stand-in for Lovecraft’s Neonomicon, to unnaturally prolong their lives. (I write extensively about those first six issues here.) Many of these characters refer to Black as some sort of “herald,” and the last six issues of Providence clarify what kind of herald he is.

Providence #8 is a turning point, though it begins almost playfully, with Black visiting Randall Carver, Moore’s version of Randolph Carter, the protagonist of Lovecraft’s “Dreamlands” stories. In the opening scene, Black and Carver discuss Carver’s theories about dreams, and from pages four to seven, Moore and Burrows alternate panels between a depiction of Black and Carver’s conversation and unexpected yet related visual detours. In the first panel of page five, Carver alludes to a past incident in a graveyard (from Lovecraft’s story “The Statement of Randolph Carter” [1920]), and while the word balloons continue the exchange between Carver and Black, the image flashes back to Carver’s horrific graveyard experience. The same technique occurs in panel three, where dialogue from the conversation is juxtaposed with another occult adventure Carver had in a graveyard (this one based on Lovecraft’s “The Unnamable” [1925].) All of page five shows this metronomic alternation between the Black/Carver talk and the visual flashbacks:

Similar back-and-forth continues for the next two pages. When Carver mentions “earliest civilizations,” the phrase is accompanied by an illustration of a Roman Centurion pledging fealty to Caesar. When Carver and Black talk about Lord Dunsany’s military service—and their own—the image is of two French Foreign Legion soldiers, one with a fatal head wound. (Black notes that he was “turned down” for the armed forces “for medical reasons,” almost certainly his homosexuality.) This switching between scenes, where the words spoken in one panel spill over into a different image in the next panel, is one of Moore’s signature techniques; think of the passage in chapter three of Watchmen where dialogue from Dr. Manhattan’s torturous television interview also acts as a running commentary on Dan and Laurie’s fight with the top-knots and their increasing attraction towards each other. The effect of this technique in Providence #8, however, is to imply that the words that Carver and Black speak reshape their (and our) perceptions of the world.

Moore has, of course, long celebrated the power of language. As Lance Parkin points out in his biography of Moore (titled, appropriately enough, Magic Words [2013]), “’Magic’ is the name [Moore] gives to instances where language can be seen to affect reality; it’s how human consciousness and imagination interact with the world” (272). And in this scene, Moore depicts the magic of a conversation so immersive and engaging that it alters the “reality” we read on the surface of the page, as prosaic scenes of two men sitting at a table drinking tea are replaced by pulpy, provocative representations of the subjects and situations that they discuss. These are powerful words, but at no point are Black and Carver overwhelmed or intimidated by language, even as their chat segues into a meditation where Carver escorts Black into the Dreamlands. Carver teaches Black “the ludic dream state,” and both venture into Dreamland realms of tentacle-faced train conductors and flying cats, until the sensation of falling up into the sky jolts them back to non-ludic consciousness. Their Dreamland trip is occasionally creepy and sometimes funny, but always safe and unthreatening—as Carver notes, to escape this or any dream, all they need do is open their eyes and fully wake up, which they do.

Two sequences at the end of Providence #8 revisit Moore’s back-and-forth patterns, but in ways considerably more sinister that the voyage to the Dreamlands. The first comes when Black meets H.P. Lovecraft himself at a fiction reading by the fantasy writer Lord Dunsany. During their first conversation, Black stammers a bit—nervous by how impressed he was by a recent Lovecraft story he’d read in the amateur literary journal Pine Cones—while Lovecraft calls himself “an elderly and blundering curmudgeon,” and uses gently self-depreciating humor to put Black at ease (in two panels from page 23):

The first panel is taken from Black and Lovecraft’s small talk, while the second is an image of Willard Wheatley, a monster-man hybrid who tried to kill Black in Providence #4. (Wheatley drags the carcass of a hooved animal to the shed where his even more monstrous brother John-Divine lives: it’s dinner time.) Over the course of eight horizontal panels over two pages, scenes of Black and Lovecraft becoming friends (and making tentative plans to reunite at Lovecraft’s home in Providence) alternate with portrait shots of the various haunted presences from Neonomicon and Providence: Johnny Carcosa’s mother (who plays a herald herself in issue #10, conducting rituals in a deconsecrated church as Carcosa, ahem, gives Black a blow job), Willard Wheatley, Elspeth Wade / Etienne Roulet, and Hezeziah Massey and Mister Jenkins.

In the above example, Lovecraft is kidding around when he calls meeting Black a “momentous encounter,” but in fact Moore treats their introduction as a supremely important event that weaves Providence’s supernatural presences into a portentous web of meaning. On the next page, a joking Lovecraft refers to the “motiveless stars” that brought the men together, and the next panel shows Elspeth / Etienne staring out a window at the starry sky. When Lovecraft shakes Black’s hand and says “I am your obedient servant,” we cut to a close-up of Hezeziah’s breasts, as Mister Jenkins—himself an “obedient servant”—finishes nursing and whips his head back to stare at the reader. The beings associated with prolonged life and mystic power who Black encounters in his travels metaphorically stand at attention when Black finally meets Lovecraft.

Providence #8, then, begins with Black and Carver confident as they tap into language’s magic and take an exciting trip to the Dreamlands. The end of the comic, however, is an ominous formal bookend, as Black’s conversation with Lovecraft is a back-and-forth sequence that summons monsters rather than magic.

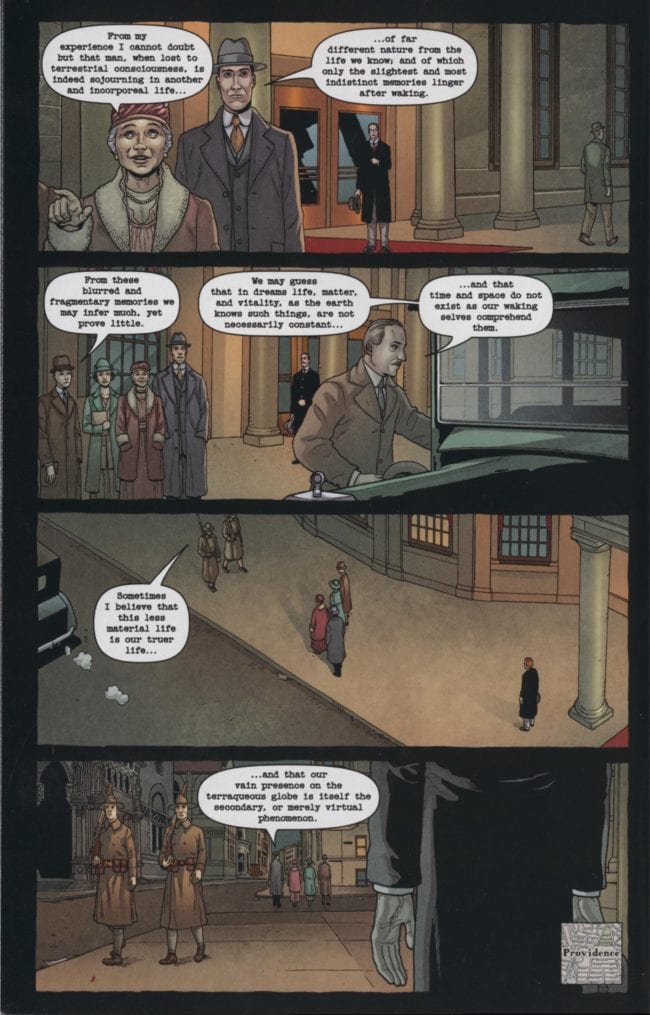

The final page of comics in issue #8 takes Moore’s disjunctions between words and images in yet another direction: Lovecraft and others stroll out of the Fairmount Hotel (the site of the Dunsany lecture) and into the Boston air, speaking to each other, but the typeface inside their word balloons look like distressed letters hammered out on an old typewriter, and their “dialogue” is an extended quote from the first paragraph of Lovecraft’s Dreamlands story “Beyond the Wall of Sleep.” Here's a key sentence from that passage, followed by the final page in Providence #8 that quotes extensively from "Beyond the Wall of Sleep":

Sometimes I believe that this less material life is our truer life, and that our vain presence on the terraqueous globe is itself the secondary, or merely virtual phenomenon.

The effect of this final page is extraordinarily creepy. The characters are reduced to marionettes, to mouthpieces for an occult presence that asserts its primacy over the creatures scuttling across the “terraqueous” Earth. The Dreamlands, and darker realms, are real, and waking life is false life. Black and Carver believe that their words and meditations can alter reality, but the conclusion to issue #8 reveals what happens when unearthly entities with their own language—Aklo, perhaps, or another language capable of breaking down the boundaries of what we call “reality”—influence our behavior rather than the reverse. This preview of catastrophe-to-come occurs immediately after the “momentous occasion” of Black’s introduction to Lovecraft.

But how does this power of language—for both good and bad—play out in the conclusion of Providence? And how does it support my claim that Providence is somehow a metaphor for Moore’s career in comics?

The Herald and the Redeemer

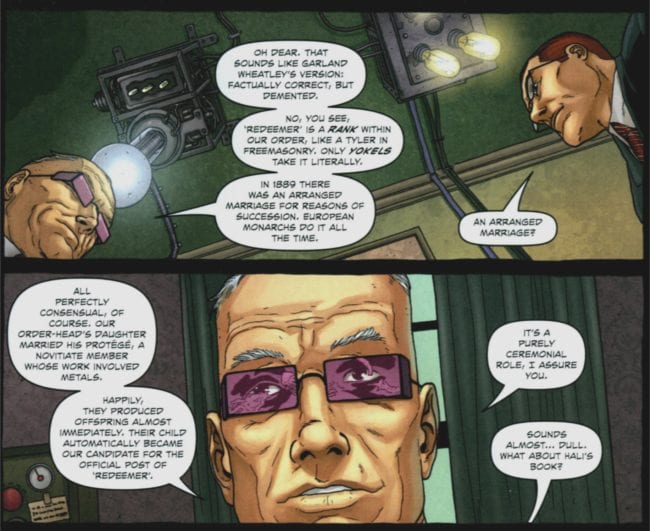

To answer these questions, I need to summarize the revelations about the roles of “Herald” and “Redeemer” that Black discovers in Providence #9-10. Moore dishes out key information in the opening pages of #9, as Black meets with Henry Annesley, an elder of the Stella Sapiente, the mystical order that Black researches throughout the series. Annesley and Black discuss the prophecy of a “Redeemer” at the core of Stella Sapiente belief, and after denouncing earlier rogue attempts to create the Redeemer by Garland Wheatley and his family (as shown in flashback in Providence #4), Annesley speaks of the Order’s official attempt, through arranged marriage, to fulfill the prophecy (page 6):

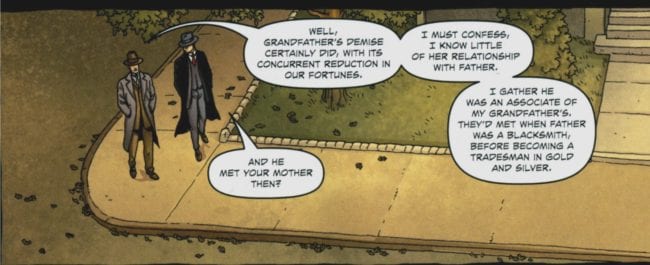

Black then drifts away from his meeting with Annesley, both for a tryst with a young man named Howard Charles, and for his first visit with Lovecraft in Lovecraft’s beloved home city of Providence, RI. During an initial stroll around the city, Black and Lovecraft chat—it’s astonishing how much of Providence consists simply of scenes of Black in compelling conversations with other men—and secure an apartment at 66 College Street for Black to rent during his Providence stay. Then, while the two walk towards Butler Hospital so Lovecraft can see his mother Susie Phillips Lovecraft, H.P. off-handedly refers to his father, “a tradesman in gold and silver” (page 22):

By presenting these two panels from Providence #9 back-to-back, I’ve made the link between the “novitiate member whose work involved metals” and the “tradesman in gold and silver” much more obvious than in the published comic, where several pages and hundreds of words separate the images. On my first reading, I missed this hint that Lovecraft’s father was the groom in the Stella Sapiente’s arranged marriage--which defines Lovecraft himself as the Redeemer. We get confirmation slightly later in issue #9, when Black and Lovecraft arrive at Butler Hospital, and Black keeps a discreet distance while Lovecraft has a disturbing visit with his mother. On page 24, tiny word balloons dramatize the physical distance between Black and the Lovecrafts, but it’s worth squinting to read Susie’s dialogue (page 24):

Susie is supposedly in the hospital because of mental illness, but her dialogue indicates that she understands the cyclopean forces shaping events in ways that “normal” people foolishly ignore. Susie asks her son, “Do you think you can redeem yourself?” and calls him “hideous” and a “monster.” (As Moore and other Lovecraft fans know, Susie was inordinately cruel to H.P. in real life—she called him “hideous” when he was a child—but Providence implies that H.P.’s Redeemer status might explain his mother’s anger and abuse.) In the last panel on the above page, Susie also describes being raped: “When he got you on me, his head was a ball of light! I was given no choice…” Her description is almost identical to the flashback scene in Providence #4 where Garland Wheatley’s renegade attempt to breed the Redeemer involved raping his daughter Leticia; the “ball of light” is a section of the Kabbalah, which hovers behind Wheatley (and seemingly possesses him) as he inseminates Leticia.

Susie’s account of events—and Lovecraft’s status as Redeemer—is bolstered by the bookend structure of Providence #9, which opens with several panels from Annesley’s point of view, as he wears special glasses that reveal creatures that swim around us on the astral plane, invisible (like the prophecies and plans of the Stella Sapiente) to our common perceptions. At issue’s end, we see the creatures again, this time through Susie’s eyes; she doesn’t need Annesley’s goggles because she’s already fully in sync with the cosmic forces manipulating the protagonists and their world. And here’s her message: Wheatley failed, but the Lovecraft marriage spawned the monster, the Redeemer, HPL.

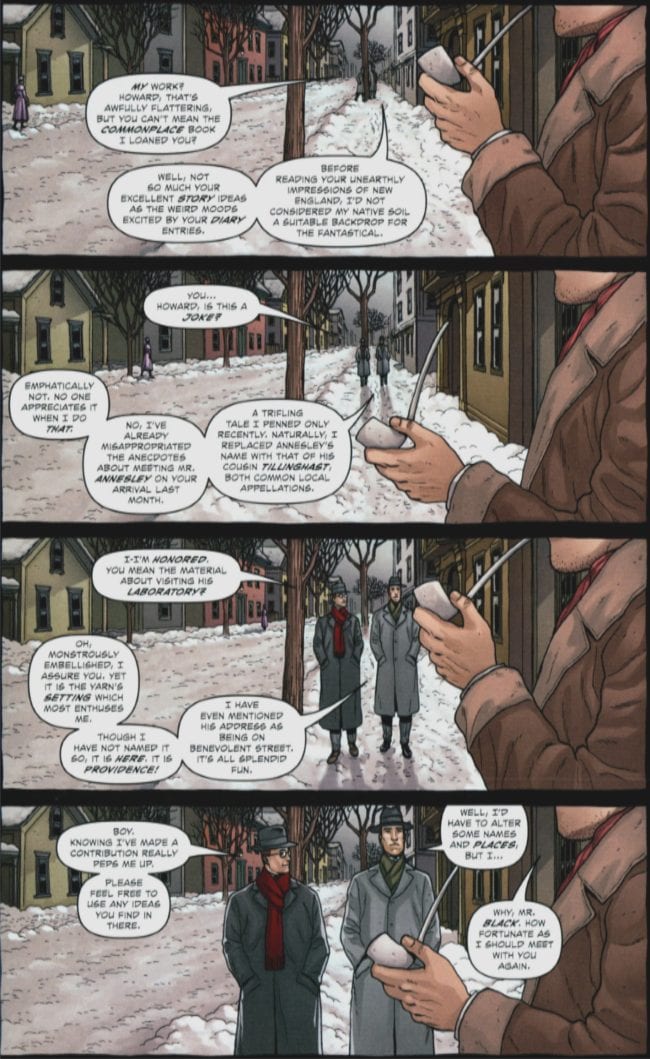

Providence #9 nails down the identity of the Redeemer, and #10 clarifies how Black serves as a Herald to Lovecraft. As we’ve seen throughout the series, Black is a researcher, a scholar who digs up knowledge about Hali’s Book of the Wisdom of the Stars, the Stella Sapiente, and New England occultists; Black then writes up what he learns in his Commonplace Book, the travel notes that appear in prose form in the back pages of issues #1-10. The specific moment of “heraldry,” then, comes when Black loans this Commonplace Book to Lovecraft—a moment that we never see, that occurs during an implied interval of time between issues #9 and #10. After reading Black’s Commonplace Book, however, Lovecraft borrows ideas and plots from Black for his classic tales. On page three, Lovecraft acknowledges that he’s “taken inspiration” from Black’s notes, after which follows page four:

Black’s encounters with Annesley, then, are embellished and shaped by Lovecraft into his short story “From Beyond” (1920/34), and we understand that Black’s Commonplace Book will inform most of Lovecraft’s future stories.

About half-way through issue #10, after a final conversation with Lovecraft, Black suddenly realizes that Lovecraft is the prophesied Redeemer; Black’s epiphany is communicated via aural flashbacks, word balloons from earlier scenes in Providence that swarm around Black like tormented ghosts. When Black is visited by—and fellated by—the enigmatic and supernaturally horrific Joe Carcosa from Moore and Burrows’ earlier Neonomicon series, we understand that Black’s delivery of his Commonplace Book to Lovecraft was somehow an earth-shattering event. In the words of Carcosa, whose vagina-like mouth presumably explains his lisp: “Your thignificanth lieth in thupplying the Redeemer with the thingth he needth to rethtore the world to itth previouth ethtate” (page 22). Black is the Herald that supplied the narrative raw material Lovecraft required to write his tales.

How will Lovecraft’s stories “rethtore the world to itth previouth ethtate”? It begins after the first nine pages of Providence #11, when Black drops out of the narrative. In despair over his role as Herald, Black surrenders to death in one of Robert Chamber’s “exit gardens,” the same euthanasia facility where his lover Lillian/Jonathan commits suicide in issue #1. (As the commentators on Facts in the Case of Alan Moore’s Providence point out, there are many callbacks to issue #1 here: the Al Jolson song “You Made Me Love You,” the locale of a Horn and Hardart cafeteria, the reappearance of Black’s friend Charles from the New York Herald.) Moore and Burrows then segue into a storytelling mode where each panel represents a drastic leap in subject, time, and space, as they race through three different unfolding stories: (1.) the fates of various characters (Dr. Hector North, Thomas Malone, Randall Carver, Willard Wheatley, others) that Black met during his investigations; (2.) the trajectory of Lovecraft’s life, including his first sale of a story to Weird Tales, his ill-fated marriage to Sonia Greene, and his death at age 46; and (3.) the emergence of Lovecraft fandom, as Moore chronicles such events as the moment before Conan the Barbarian creator and Lovecraft correspondent Robert E, Howard shoots himself in the head, the early publishing efforts of August Derleth and Donald Wandrei’s Arkham House Press, and the saga of Robert Barlow, whose bad fortune as both Lovecraft’s literary executor and as a closeted gay professor at Mexico City College was the subject of 2017’s novel The Night Ocean by Paul La Farge.

What becomes clear as Providence #11 barrels on is that interest in Lovecraft quickly expands beyond science-fiction and horror cultists, to inspire both “high-brow” authors (William S. Burroughs and Jorge Luis Borges have cameos here) and unscrupulous publishers looking to make a quick buck by peddling their own “real” versions of The Necronomicon. Lovecraft’s expanding influence then grows malevolent and apocalyptic: Funko Pop Cthulhus sour into ritualistic killings and the dark events of Neonomicon, where F.B.I. agent Aldo Sax eviscerates his neighbor and agent Brears is repeatedly raped by one of Lovecraft’s fish-man Deep Ones. In Providence, Lovecraft’s fiction spreads like a meme (or a "virus from outer space"), summoning occult forces to reshape the world. According to Moore, the combination of Black’s research and Lovecraft’s create a language (or at least a mode of expression) potent enough to change reality permanently, in ways that go far beyond the marionette-like manipulation of humans by Lovecraftian language at the end of Providence #8. By issue #12, everyone who’s still alive now lives in a world inhabited by Night-Gaunts and Elder Gods like Cthulhu, Azathoth, and Shub-Niggurath. This is the “redemption” that HPL the Redeemer delivers through his fiction; this is the dark side of the magical power of language.

Here, then, is the basic plot of the last four issues of Providence: an author (Lovecraft) is inspired by an already-extant set of characters and relationships (from Black’s Commonplace Book) to write his own version of the material, adding his own formal innovations and narrative twists. The result is unexpected success and influence (though Lovecraft’s popularity and success came posthumously, both in the real world and in Providence). This plot is an implicit celebration of fan-fiction, an argument that originality in storytelling is less important than the capacity to re-make and reboot established “universes” in clever and compelling ways. Consider the Cthulhu Mythos: one reason for Lovecraft’s continued relevance is the thousands of fan-fic contributions (by creators as diverse as Joyce Carol Oates and the raunchiest, most obscure Deviantart cartoonist) to Lovecraft’s Arkham, Massachusetts, Miskatonic University, and the planet Yuggoth. In Providence, Moore wittily constructs a situation where Black the Herald delivers a roughly-outlined supernatural world to Lovecraft, and Lovecraft himself adapts that material, becoming the very first contributor to the Cthulhu Mythos, the first fan-fic writer about a world that Providence defines as real.

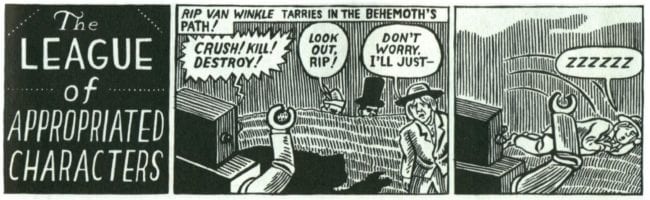

But let’s quote that bare-bones plot summary again: “An author is inspired by an already-extant set of characters and relationships to write his own version of the material, adding his own formal innovations and narrative twists. The result is unexpected success and influence.” Doesn’t this describe Moore’s career as much as Lovecraft’s? Moore is perhaps best known for his new spins on established characters and franchises; examples include Swamp Thing, the Charlton Action Heroes, and what Michael Kupperman might call “the League of Appropriated Characters,” the public domain icons (The Invisible Man, Mr. Hyde, the Lost Girls, Cthulhu) that dominate Moore’s recent work.

This celebration of artistic adaptation turns Providence into a commentary on Moore’s career. Moore is Providence’s version of Lovecraft, an author whose gifts and importance lies—at least partially—in the elaboration of previously established fictional worlds. Perhaps the connections between Moore and Prospero that opened this essay make the same point; after all, Shakespeare was himself a super-adaptoid, plundering plots, ideas, and language from Boccaccio and Plutarch, from both dead writers and his contemporaries. And throughout his career, Moore’s ability to borrow from—and, further, to channel—the voices of his literary inspirations have been uncanny. Near the beginning of his career is his remarkable version of Walt Kelly’s Pogo “swamp-speak” in the Swamp Thing story “Pog”; more recent is Moore’s Finnegans Wake-inspired portrait of Lucia Joyce in Jerusalem. And in between, Moore has written himself into literary history through allusion, pastiche, postmodern appropriation, parody, and his willingness to play, innovatively, in other authors’ sandboxes.

It’s tempting to wonder why Moore felt that he needed to create in-comic avatars of himself as his career in comics winds down. Moore has written metafictional comics before—Supreme was both Moore’s commentary on the “dark” superheroes of the 1990s and an elegant solution to his financial need to return to writing superhero comics—but he’s at a different place now, a place where he wants to clarify his legacy and defend the legitimacy of his appropriative aesthetic. And perhaps Moore doesn’t believe that contemporary comics culture gives him the credit he deserves. On December 14, Jeet Heer tweeted about Jack Kirby and Steve Gerber’s satire of Marvel Comics (“Grab It All, Own It All, Drain It All”) in the series Destroyer Duck (1982-84), and commentator and retailer Chris Butcher responded thusly:

If Jack Kirby were alive we’d treat him the same way we treat Alan Moore, totally respectful until he got in the way of us enjoying our precious, precious content, then he could fuck right off. We’d write thinkpieces about how he wasn’t really that great anyway.

Butcher’s tweet nicely summarizes a common way that Moore is currently discussed in fannish circles: as a crazy old man (with his theories about magic and language trotted out as Exhibit A of his nuttiness) whose diatribes about creators’ rights and the limitations of the superhero genre are a buzzkill. Why the Hell isn’t Moore excited about an HBO version of Watchmen like the rest of us? In our media-soaked, synergized culture, fans expect their desires and pleasures to be immediately fulfilled, and are enraged that Moore doesn’t deliver what they want. And Moore keeps working on the fringes of the comics industry, writing odd (and strikingly ambitious) stories about Prospero and Lovecraft, writing his epitaph, writing comics that will last.