Fondly catalogued as the first comic strip in which the characters aged, Gasoline Alley was created by Frank King in 1918 at the behest of Chicago Tribune publisher Colonel Robert McCormick, who wanted a feature that would appeal to people learning how to take care of their cars, which, thanks to Henry Ford, were becoming increasingly available to a middle class public. And King was just the man to do the new feature: he was as thoroughly middle class as he could be.

King grew up in west-central Wisconsin: born in 1883 in Cashton, he was raised in nearby Tomah, where, at the age of 15 or 16, he went to work on the local paper for a year or so. After high school, King spent four years newspapering at the Minneapolis Times and then, at the age of about 22, went to Chicago where he studied for two years at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts while working Saturdays at the Chicago American. He worked for a short time at an advertising agency in Chicago and then joined the art department at the Chicago Examiner for three years. In 1909, King was lured to the Chicago Tribune by a better salary, and in 1911, he started doing a daily cartoon feature called Motorcycle Mike and a Sunday color comics page, Bobby Make Believe. Later, King filled-in briefly for John T. McCutcheon when the Tribune's celebrated front-page editorial cartoonist went to Europe to reconnoiter the outbreak of war there.

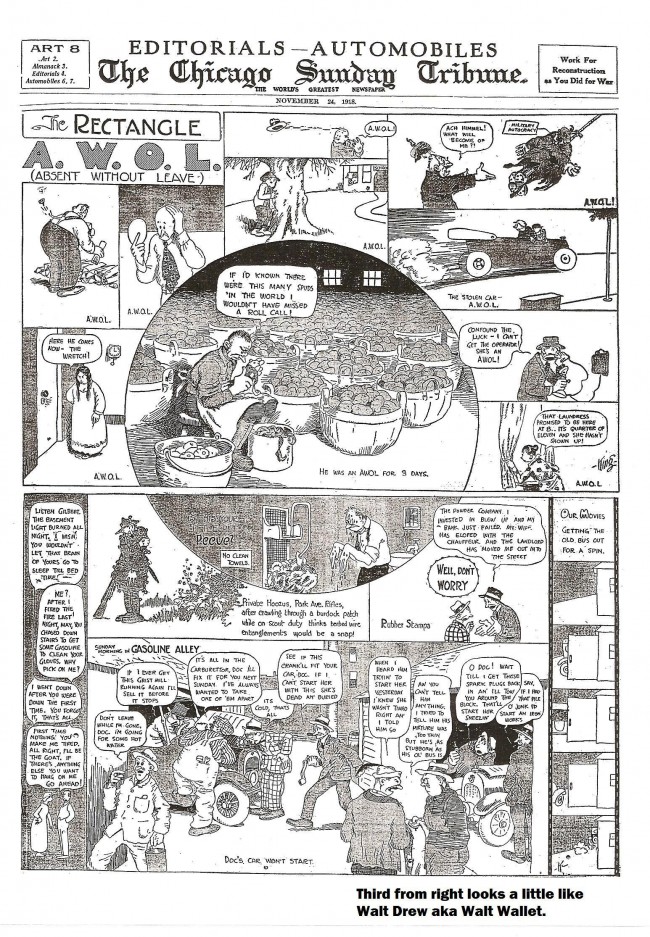

In addition to his Sunday color strip, King was doing a black-and-white Sunday feature—a miscellaneous collection of topical cartoons grouped together in the embrace of a single page-sized panel called "The Rectangle."  Some of the cartoons explored a common theme (here, “A.W.O.L.”), but others appeared regularly, week after week, under such departmental headings as Familiar Fractions, Pet Peeves, Science Facts, Our Movies. And as we see in the neighboring illustration, on November 24, 1918, in response to McCormick’s order, King started a new department: set in an alley where men met to inspect and discuss their vehicular passions, Sunday Morning in Gasoline Alley was all about automobiles.

Some of the cartoons explored a common theme (here, “A.W.O.L.”), but others appeared regularly, week after week, under such departmental headings as Familiar Fractions, Pet Peeves, Science Facts, Our Movies. And as we see in the neighboring illustration, on November 24, 1918, in response to McCormick’s order, King started a new department: set in an alley where men met to inspect and discuss their vehicular passions, Sunday Morning in Gasoline Alley was all about automobiles.

A recognizable Walt Wallet doesn’t seem to be among the alley’s denizens on November 24: the only one chubby enough is third from the right, in the foreground, holding an inner tube in his hands; but except for girth, he doesn’t look much like our Walt. He does, however, look a little like King’s brother-in-law, Walt Drew, upon whom the cartoonist modeled Walt Wallet.

“I pounced on my brother-in-law for my leading character,” King wrote in one of the first Gasoline Alley reprint volumes, “—not, however, because he was particularly well-fitted for a comedian but because he was handy and he was good-natured. Almost anyone, with a little exaggeration, would make a good comic character. There is no lack of raw material. Not only the woods, but the streets and houses are full of it. I have taken infinite liberties with Walt’s physique, his mentality and his daily activities, and I believe that my original guess that he would stand for a lot has proven correct.”

The automobile corner in King’s weekly cartoon was a success. "Cars had character in those days," King said once, "and there was plenty to discuss." And plenty of interest in the subject and in King's treatment of it: in nine months, Gasoline Alley had outgrown "The Rectangle," and King had found his life's work.

The new panel offered up its mild gags routinely on Sundays until Monday, August 25, 1919, when it began to run daily as well, sustaining a modest continuity. Although it ran for the first time as a multi-panel square-format cartoon on August 17, it continued mostly in single-panel format until October, after which it was sometimes a single panel and sometimes multi-panel. By mid-winter, it was usually in multi-panel form but the panels were stacked into a square rather than running as a “strip” in a single tier sequence. The single-panel treatment appeared less and less frequently; it’s last appearance was April 23, 1921. By then, the horizontal strip format had emerged as the prevailing mode.

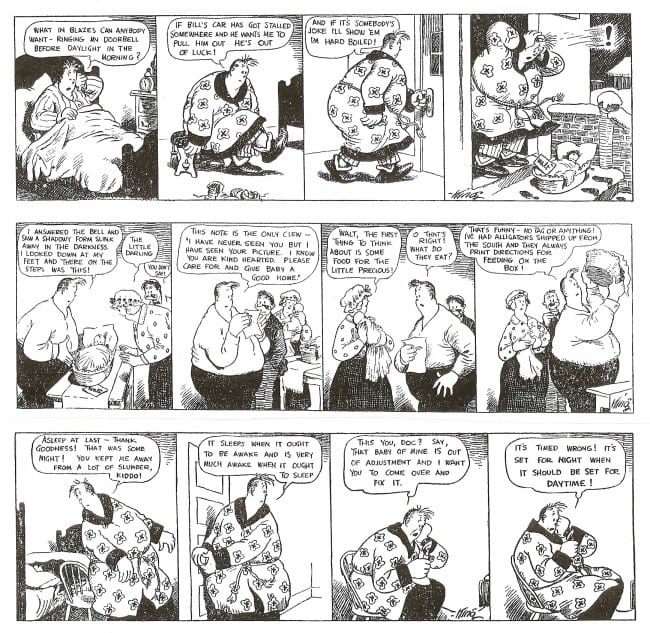

The traditional cast took shape in very few weeks. “Doc” was in the first Gasoline Alley by name and physiognomy, van dyke beard in full bloom. Doc Johnson, a practitioner of medicine in Tomah, was King’s inspiration even though clean-shaven. Doc and Walt were in almost every panel for the first months of the cartoon, but Walt wasn’t named until December 15, 1918. Even so, he was not recognizably our Walt until about February 1919, by which time, his distinctive forelock and girth were well-established.

King turned to a friend, Bill Gannon, for another character: Bill was present but unnamed in the second Alley on December 1, 1918; he’s named March 9, 1919. Avery showed up by name on December 22, 1919, and he’s the principal in the first multi-panel Alley the following summer on August 17: therein, he’s been cautioned not to swear as he works on his car in front of a kid named Elmer; they both star in the second multi-panel Alley on September 21. Dedicated mechanic and annoying juvenile observer—sure-fire comedy material.

Said King: “Avery possesses the economical instincts claimed by the Scotch but by no means peculiar to them. Avery was not taken bodily from real life but is pieced together from many human fragments. I do not agree with some alleged authorities that I furnished most of them myself. No, Avery is synthetic Scotch.”

The foregoing cast origins were culled from Spec Productions’ publication of the first couple years of Gasoline Alley (November 1918 - December 1920) in four photocopy 8.5x12-inch landscape format booklets.

For a while, King focused exclusively on the car talk of his regular cast (Walt, Doc, Avery, and Bill), and then in 1921, Colonel McCormick’s cousin, partner and head of the Tribune-Daily News syndicate, Captain Joseph Patterson, decided that the cartoon would be even more popular if something in it appealed to women. "Get a baby into the story fast," he commanded the flabbergasted King, who protested that Walt, the main character, was a bachelor. It was then decided to have Walt find a baby in a basket on his doorstep—which he did on Valentine's Day, 1921.

With the arrival of the baby, the strip developed a stronger storyline. For instance, Walt took several days just to get the neighborhood's approval of the name he had chosen for the infant boy. “Skeezix” was Walt’s first choice, a slang term of endearment for a small child (akin to “squirt” or, even, “tyke”). Eventually, the boy was formally christened Allison: Alley-son, a son of the Alley.

Subsequently, almost accidentally, the strip evolved its most unique feature: its characters aged. The children grew up, and the adults grew older. To King, this innovative aspect of his strip was simply logical. "You have a one-week old baby, but he can't stay one week old forever. He had to grow." By logical extension, so did everyone else in the strip. Patterson concurred. This attribute of Gasoline Alley added a dimension of real life to the strip, and King went on to convert everyday concerns about automobiles into a larger reflection of American life in a small town.  With the baby Skeezix absorbing Walt’s attention, the cartoon took on familial overtones although Walt, quaintly, persisted in using automotive terms to describe Skeezix’s activities. As a strip, Gasoline Alley was thoroughly domestic, its situations those of everyday life; its humor, warm, pleasant, low-keyed and thoughtful. All of which is amply displayed in Drawn & Quarterly’s elegant hardcover series that begins with January 1921 and is now several volumes into Frank King’s tenure on the feature.

With the baby Skeezix absorbing Walt’s attention, the cartoon took on familial overtones although Walt, quaintly, persisted in using automotive terms to describe Skeezix’s activities. As a strip, Gasoline Alley was thoroughly domestic, its situations those of everyday life; its humor, warm, pleasant, low-keyed and thoughtful. All of which is amply displayed in Drawn & Quarterly’s elegant hardcover series that begins with January 1921 and is now several volumes into Frank King’s tenure on the feature.

Walt married Phyliss Blossom in 1926, and the couple had a child, Corky, in 1928; then in 1935, Walt found another orphan, a girl this time—Judy. As Skeezix grew up, the strip traced his life—elementary school, high school, graduation, his first job (on a newspaper), the Army in World War II. Skeezix became engaged to Nina Clock during the War, and they got married, and after the War, Skeezix took a job running the neighborhood gas station. Then they had children—first Chipper, then Clovia—and the cycle of growth, maturation, marriage and family began anew. Gasoline Alley stayed small town America throughout King's tenure, and it was wholesome through and through.

King's graphic style (in the “Chicago school” of Carl Ed, Sidney Smith, and Harold Gray) was not particularly distinguished—pedestrian linework embellished with routine shading and occasional cross-hatching—but it was thoroughly competent and perfectly suited to the unpretentious, homey, everyday preoccupations of the strip. In the daily strips, King seemed quite content to plod competently along, watching his characters grow older and exploring the concerns of ordinary Americans.

But on the Sunday pages in the thirties, his graphic imagination bubbled to the surface, and he produced some of the most inventive strips in the history of cartooning. Once Walt and Skeezix strolled through a countryside rendered in the style of modern German expressionism; another time, they walked through a woodcut autumn. In some of the Sunday strips, Skeezix slipped into a dream-like fantasy, a reminder, for those who might remember, of King’s Bobby Make Believe.

And once King drew a full-page bird's-eye view of the Wallet neighborhood, and then, by imposing the usual grid of panel borders on the scene, he ingeniously created 12 independent vignettes. The result was a portrait of backyard society in double-exposure: over-all, the page showed us the geography of the neighborhood while the characters in actions and words in each panel enacted the life of that neighborhood. King performed a similar feat for a day at the beach.

But King made his mark in comic strip history not with such spectacular displays but through the more mundane device of aging his characters—which is a shorthand way of referring to the life he breathed into them, life that seemed real to readers and built a devoted readership that followed the strip even after King died. No small accomplishment. And King was quite aware early in his career of the effects he was producing.

At the conclusion of his notes to the Gasoline Alley reprint from which I quoted earlier, King wrote: “I hope my audience will get a measure of interest and fun out of these pictures. I had pleasure in drawing them. It is a privilege to be the master of destinies, and director of every urge and event in the lives of such a group of folks. They may be dream folks, but the responsibilities are real because I know these characters are real to many thousands of readers. ... Personally, I am not convinced they are dream folks. They have furnished me and mine for years with the solid basic materials of life ... I, for one, know they are real.”

In 1951, Bill Perry began doing the Sunday page, concentrating on stand-alone gags. Perry has long played the chief supporting role in a Frank King myth.  King, according to the legend, held that anyone could learn to draw, and to prove his point, he bet a few of his cronies in the Tribune cartooning suite that he could teach the mailroom delivery boy, Perry, to be a cartoonist. According to report, he gave young Perry a pad and pencil and sent him out into the world to draw everything he saw. After a while, Perry could draw, and in 1926, King took him on as his assistant, from which lowly station, Perry eventually graduated to do the Sunday Gasoline Alley.

King, according to the legend, held that anyone could learn to draw, and to prove his point, he bet a few of his cronies in the Tribune cartooning suite that he could teach the mailroom delivery boy, Perry, to be a cartoonist. According to report, he gave young Perry a pad and pencil and sent him out into the world to draw everything he saw. After a while, Perry could draw, and in 1926, King took him on as his assistant, from which lowly station, Perry eventually graduated to do the Sunday Gasoline Alley.

Much of that is true, but what is usually left out is that Perry, in addition to being the mailroom boy, was at the time helping Carl Ed on the Harold Teen comic strip; he was scarcely an untutored drawing novice. At the time Perry took over the Sunday Gasoline Alley, he was doing a Sunday strip of his own, Ned Handy, Adventures in the Deep South, which he’d launched in 1945 while continuing to assist King but gave up when he went solo on the Sunday Alley.

In 1956, Dick Moores started assisting King on the dailies. Moores came to the Alley by way of the Disney Studios, where he’d been working since 1942 on such comic strips as Uncle Remus and Scamp. Before assuming his Disney duties, Moores had assisted Chester Gould on Dick Tracy for about five years, graduating to his own crime-fighting strip, Jim Hardy, in 1936. A few years later, two minor characters in the strip, a simple-minded but virtuous cowboy named Windy and his faithful and nearly sentient race horse Paddles, usurped Hardy, and Moores re-named the strip for them. But even as a horse opera, the strip lost circulation; Moores finally quit and went to work for Disney.

During the Jim Hardy/Windy and Paddles years, Moores had shared a studio with King, and when King needed help on the Alley, he was reminded of his old studio-mate by Perry, who, according to the Alley’s current custodian, Jim Scancarelli, regularly went golfing with Moores during their Chicago days in the 1930s. Moores claimed he began writing Gasoline Alley as soon as he arrived, but Scancarelli said Perry had told him that didn’t happen quite that way. By 1960, however, Moores had taken over almost entirely, writing and drawing the strip, and King went into semi-retirement until he died in 1969. Moores’ reign on the feature is embraced by IDW Publishing’s Library of American Comics series of Alley reprints which begins with 1964.

Moores continued the strip in the same vein King had mined so well, but he paid more attention to characterization—particularly with the women—and visually, he varied his compositions more dramatically and played extravagantly with textures. Moores' sense of humor, while still wholesome and low-keyed, was somehow warmer, more human. And his comic imagination was much more inventive than King's. Under Moores' stewardship, two characters outside the Wallet family emerged as the prominent comic figures in the strip. Rufus the handyman and Joel the junkman, who propelled themselves with uncanny regularity into antic predicaments of the wildest sort, were also compelling portraits of loneliness whose poignant albeit comedic mutual dependency underscored their individual solitude.  King had employed other assistants over the years—Sals Bostwich, probably the first according to Scancarelli; John Chase, Val Heinz, Albert Tolf, and Jack Fox, who went on to assist Ed Dodd on Mark Trail. Perhaps the most picturesque in name and career was Bob Zschiesche (pronounced “zeee-chee”), whom King hired in early 1950 to assist him and, later, Perry. But Zschiesche didn’t last long after Moores took over: Scancarelli, the present mechanic in the Alley, told me that Moores subsequently convinced King to fire Zschiesche because he, Moores, could do what Zschiesche was doing (and he could make more money if he did). But when Perry retired in 1975 and Moores faced the Sunday strip as well as the dailies, he hired Zschiesche again to help on the Sundays.

King had employed other assistants over the years—Sals Bostwich, probably the first according to Scancarelli; John Chase, Val Heinz, Albert Tolf, and Jack Fox, who went on to assist Ed Dodd on Mark Trail. Perhaps the most picturesque in name and career was Bob Zschiesche (pronounced “zeee-chee”), whom King hired in early 1950 to assist him and, later, Perry. But Zschiesche didn’t last long after Moores took over: Scancarelli, the present mechanic in the Alley, told me that Moores subsequently convinced King to fire Zschiesche because he, Moores, could do what Zschiesche was doing (and he could make more money if he did). But when Perry retired in 1975 and Moores faced the Sunday strip as well as the dailies, he hired Zschiesche again to help on the Sundays.

Zschiesche had just retired after 12 years doing editorial cartoons for the Greensboro Daily News in North Carolina and was tinkering with an idea he had for a different kind of editorial cartoon that he thought he might do. Preoccupied with this aspiration, he devoted less and less time to Gasoline Alley: Moores found himself doing more and more of the Sunday strips while Zschiesche dawdled for weeks over one installment. Finally, in 1980, Moores let Zschiesche go and took on all seven days of the strip. He’d hired Scancarelli to assist on dailies the previous summer; Jim’s first daily was published December 27, 1979. Zschiesche’s last Sunday was dated April 6; Jim’s first, April 13.

Zschiesche went off to pursue his new approach to editorial cartooning: he depicted ordinary citizens commenting on their concerns, but every cartoon was set in an actual locale with the people standing in front of picturesque Victorian houses or local landmarks. Calling it Our Folks, Zschiesche syndicated it himself in 1980: traveling around the country as his own salesman, he eventually signed up 38 papers. About self-syndication, Zschiesche said: “I wouldn’t recommend it. It’s a crapshoot—but it’s great fun.” He ended the feature after a short run and retired, again, to the family farm near Prophetstown, Illinois. But he couldn’t stop cartooning. He did a comic strip with anthropomorphic farm animals for the local paper; that was its entire client list, but Bob was happy drawing the strip regardless of its circulation. He also tried his hand at a strip about teenagers, samples of which he showed me at the time; it was like just about any strip about teenagers you might name. Bob was, by then, too shy and self-effacing to try to sell it. He died a short time later. He deployed a crisp fustian drawing style with great eye-appeal; I wish Our Folks had made it big and lasted a long time.

He ended the feature after a short run and retired, again, to the family farm near Prophetstown, Illinois. But he couldn’t stop cartooning. He did a comic strip with anthropomorphic farm animals for the local paper; that was its entire client list, but Bob was happy drawing the strip regardless of its circulation. He also tried his hand at a strip about teenagers, samples of which he showed me at the time; it was like just about any strip about teenagers you might name. Bob was, by then, too shy and self-effacing to try to sell it. He died a short time later. He deployed a crisp fustian drawing style with great eye-appeal; I wish Our Folks had made it big and lasted a long time.

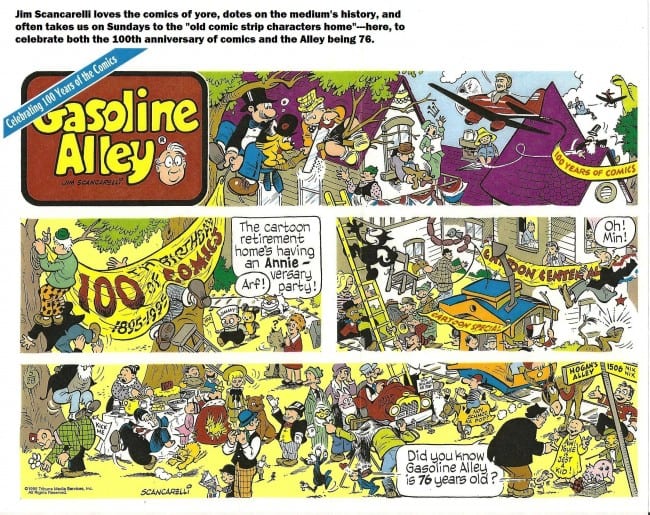

Perry worked on the Alley longer than King—49 years vs. King’s 42. And Scancarelli, who inherited the strip when Moores died in 1986, has now been doing it single-handedly and signing it for 26 years; counting his assistantship years, he’s been in the Alley for 32 years, surpassing Moores’ 30-year shift.

“When I was introduced to Dick Moores in 1977,” Scancarelli remembered in a 1988 speech given at the Smithsonian, “I met one of my heroes and two years later when he needed an assistant, I jumped at the chance to join him.”

For the next several years until he took over the strip, Scancarelli submerged himself in Gasoline Alley and its people: he latched onto everything he could learn from Moores, and he studied all of his and King’s strips.

When it became his lot to carry on the Alley tradition, Scancarelli said, he didn’t think of himself as the creator—“that was Frank King”; he was, rather, “a perpetuator.”

Scancarelli confesses to be daunted occasionally by the blank white space on the paper in front of him, but with comedy roots in radio’s “Amos and Andy” and Jack Benny, he takes advantage of whatever he sees and hears: “I remember a remark from an idle conversation or pick up on a clue from a friend, and everything starts to come together. It works just like Dick Moores said it would.”

The Alley characters have such well-defined personalities that once Scancarelli sets up a situation, he said, “They all go about doing what they should, and I observe and write it all down.”

Like everyone else who has worked on the strip, Scancarelli has successfully preserved its essential wholesome, small-town America ambiance. Rufus and Joel still do an occasional antic turn, but Scancarelli’s Gasoline Alley is more in the tradition of King than of Moores. The comedy arises naturally out of situations rather than being contrived solely for the sake of a laugh. And Scancarelli faces a predicament King never contemplated when he started aging his characters: what to do about one of them, Walt Wallet, the original star performer, who has aged well beyond his 110th birthday. Walt can’t live forever, but can Scancarelli let him die? Jim knows what he’ll do, eventually, but he isn’t talking.