In 1988, Guy Colwell, a forty-three-year-old painter of solo show-worthy, socially conscious, surrealist oils, returned to comics. More than a decade earlier, Colwell had written and drawn the five-issue series Inner City Romance (Last Gasp. 1973-78). Those books had been summoned from him by serving eighteen months in federal prison for draft resistance and a post-release, roach-infested residence on the border between San Francisco’s Haight Asbury and Western Addition neighborhoods, while hanging with a heroin addict he knew from the joint. Patrick Rosenkranz, the Herodatus of underground comics, has celebrated ICR, in his introduction to Fantagraphics’s forthcoming one-volume collection of this title, for its focus on “prison, black culture, ghetto life, the sex trade, and radical activism.”

Colwell brought a new level of sustained political fervor to the UG. ICR sold as many as 50,000 copies an issue, but once he had quelled the demons those comics had confronted, Colwell had put the medium aside. Still, he valued its ability to immediately connect to the here-and-now. A painting could take him six months. But he could complete a comic in thirty days. “Comics,” he told Rosenkranz, “were rock’n’roll. Paintings are a symphony.”

Doll (Rip Off. 1989-95)[1] was written with a consciousness that remained engaged with and troubled by the world. At the time, Colwell was living in a second-hand mobile home in the western foothills of the Sierra Nevadas and working part-time as a typesetter and graphic artist. He had been through one marriage and several short term relationships. Now, he announced in his introduction to the first issue, personal experience had led him to explore “sex... desire... greed... caring (and)... especially loneliness.”

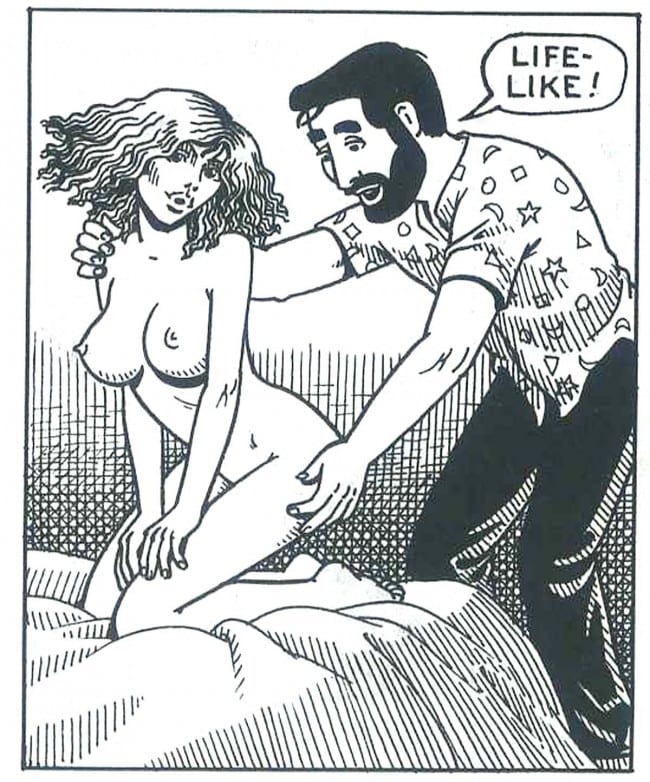

Doll, the eponymous title character, is a sort-of spawn of Phoebe Zeitgeist and a Schmoo. Like the former she is much abused, yet like the latter she is ultimately deemed a threat to mankind which must be destroyed. She is also, most importantly, a gorgeous, seductive – but plastic-and-rubber replica of – a woman. She has been created with all-orifice-exactness by a sculptor (Wiley Waxman), assisted by an anatomist, cosmetologist and gynecologist, at the request of a man (Evergood Crespok) born so hideously deformed that he has never been able to convince a woman to have sex with him and wishes to experience the as-close-as-possible next best thing. But Doll proves so desirable that she is pursued and fought over by a porn magazine publisher (Mal Murphy), movie producer (Sid Glib), philosopher (Holger Hedrunn), some horny teenage boys, several hornier older men (and women), and roaming packs of the homeless, punks, gangstas, and skin heads.

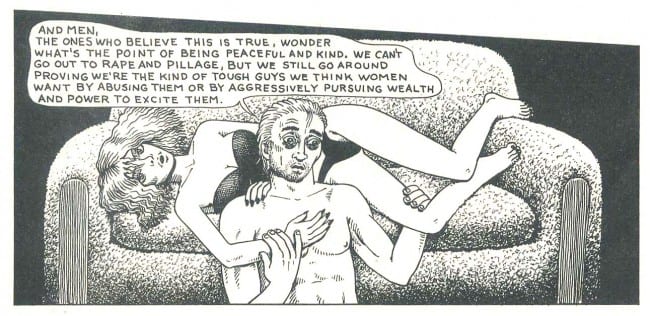

Colwell began the series with a three-issue story, which one reader – my esteemed and highly insightful wife – termed “deeply sweet and deeply sad.” (It even offered a sliver of optimism, positing “a caring community” as the way “to help the lonely find love.”) But things turned with issue four. Colwell’s new introduction recounted a female former co-worker’s remark that women prefer men who treat them cruelly to those who offer “kindness, respect and support.” This leads Hedrunn, “a man mad with loneliness,” who replaces Crespak as the central character, and whose surrogate lover Doll now becomes, to inquire into the “nature of male, female relationships” in the hopes of understanding his solitude. He posits that primitive women’s desires for aggressive, cunning, abusive mates, whose qualities evidenced genes that would give her children the best chance of survival, has been carried into and reinforced by the modern world, through popular culture’s championing brutish heroes over the mild and bookish and the media’s celebration of the pursuit of wealth and power over the quest for peace and contemplation. “(O)bnoxious dominance is far more successful at attracting women,” Hedrunn concludes, than “gentle, loving, non-abusive (conduct).” From this inquiry, Doll’s final issues flow.

Colwell began the series with a three-issue story, which one reader – my esteemed and highly insightful wife – termed “deeply sweet and deeply sad.” (It even offered a sliver of optimism, positing “a caring community” as the way “to help the lonely find love.”) But things turned with issue four. Colwell’s new introduction recounted a female former co-worker’s remark that women prefer men who treat them cruelly to those who offer “kindness, respect and support.” This leads Hedrunn, “a man mad with loneliness,” who replaces Crespak as the central character, and whose surrogate lover Doll now becomes, to inquire into the “nature of male, female relationships” in the hopes of understanding his solitude. He posits that primitive women’s desires for aggressive, cunning, abusive mates, whose qualities evidenced genes that would give her children the best chance of survival, has been carried into and reinforced by the modern world, through popular culture’s championing brutish heroes over the mild and bookish and the media’s celebration of the pursuit of wealth and power over the quest for peace and contemplation. “(O)bnoxious dominance is far more successful at attracting women,” Hedrunn concludes, than “gentle, loving, non-abusive (conduct).” From this inquiry, Doll’s final issues flow.

Over the course of her tale, Doll is “raped” orally, anally and vaginally. She is penetrated digitally and with foreign objects. She is gang-banged and made the center of multiple orgies. She causes at least one suicide, two murders, the collapse of a spiritual commune, and a riot which police and the National Guard must quell. Eventually Waxman concludes that, unless she is done away with, she will forever “gnaw away at the serenity of the world...”

Colwell brought his full compliment of illustrative skills – and a fine array of cartoonist’s chops – to his comics’ pages. (As a bonus, their covers display eye-catching reproductions of his water colors and oils.) The angles of viewing and perspectives he provides his landscapes and street scenes enrich their moods and heighten the drama of the actions that occur within them. He shifts shots of his cast, from front to rear to profile, cutting back and forth between speakers, to keep his reader’s eye engaged. He varies close-ups and long shots. He shapes individual characters to convey their inner selves and allows even the most disagreeable among them some affecting spark shifting emotions. He captures rage, tenderness, frustration, curiosity, despair with equal artistry. And in group portrayals, of which there are many, each member’s self resonates with a particularity to be absorbed and considered.

Most of Colwell’s panels are straightforward explications of his in-the-story reality. But certain passages explode like an Elvin Jones upon a Keith Jarrett solo. One is the unsettling darkness with which Colwell blankets night clubs, back alleys, and unlit rooms. A superb example occurs in issue #5, when the homeless Eddie sneaks into Waxman’s studio. The panels progress through darkening grays to near complete blackness as Eddie moves from a world with which he is familiar into a new and startling one. Another jarring device is the dream sequences, dissolving borders, commanding an entire page, which serve Colwell as did the hallucinatory drug scenes of ICR. They allow his imagination full flow to expand with serpentine tongues, throttling appendages, possible paradises, potential hells . As with the darkness, through these dreams, Colwell confront his audience with suggestions of what, within and without them, influence their days and shape their nights and into which any step can drop them.

Most of Colwell’s panels are straightforward explications of his in-the-story reality. But certain passages explode like an Elvin Jones upon a Keith Jarrett solo. One is the unsettling darkness with which Colwell blankets night clubs, back alleys, and unlit rooms. A superb example occurs in issue #5, when the homeless Eddie sneaks into Waxman’s studio. The panels progress through darkening grays to near complete blackness as Eddie moves from a world with which he is familiar into a new and startling one. Another jarring device is the dream sequences, dissolving borders, commanding an entire page, which serve Colwell as did the hallucinatory drug scenes of ICR. They allow his imagination full flow to expand with serpentine tongues, throttling appendages, possible paradises, potential hells . As with the darkness, through these dreams, Colwell confront his audience with suggestions of what, within and without them, influence their days and shape their nights and into which any step can drop them.

Aside from a wish to understand his isolation, Doll also resulted, Colwell confesses, from his need for cash. The understanding of male-female relations he sets forth, while earnest, was unlikely to have drawn the interest and dollars of those with life experiences any wider than, say, those of Robert Crumb, whose work had voiced similar sentiments. For other shoppers, whom, having seen Crumb’s bio-pic, I would estimate is most of us, the likely reaction to the book’s thesis was captured by my previously cited wife who, when I explained how Doll played out, uttered “OY!”[2]

Aside from a wish to understand his isolation, Doll also resulted, Colwell confesses, from his need for cash. The understanding of male-female relations he sets forth, while earnest, was unlikely to have drawn the interest and dollars of those with life experiences any wider than, say, those of Robert Crumb, whose work had voiced similar sentiments. For other shoppers, whom, having seen Crumb’s bio-pic, I would estimate is most of us, the likely reaction to the book’s thesis was captured by my previously cited wife who, when I explained how Doll played out, uttered “OY!”[2]

As for me, seventy years witness have led me to believe that aggression and power do not determine the outcome of most courtship competitions along the evolutionary line-up this side of those of the great apes. I think physical attraction and shared interests, filtered through the web of wiring left the parties by their interactions with their moms and pops are more crucial than financial statements in determining who walks into which sunsets with whom. (On the other hand, I concede that part time work and trailer living would place one at a disadvantage whether the matchmaking lays in the hands of genes or psyches, eHarmony, or your village shakhin.)

In any event, aware that ideology alone was unlikely to amplify his market share, Colwell amped it with the commercial allure of bare bodies. Very bare bodies. Often with emphasis gynocologic or urologic exactness. And this brought Doll the “ADULTS ONLY” designation which interested me more than debating Colwell’s premise.

The First Amendment notwithstanding, our society’s right to stifle creative works that might stimulate disruptive behavior, especially when this behavior is sexual or violent, has become a given. And though it is the behavior of adults which is usually most damaging to society in these areas, it is juveniles who have their access to these works most restricted. And though violence seems to damage society more severely than sex, it is sexual work that is restricted most rigorously.

The First Amendment notwithstanding, our society’s right to stifle creative works that might stimulate disruptive behavior, especially when this behavior is sexual or violent, has become a given. And though it is the behavior of adults which is usually most damaging to society in these areas, it is juveniles who have their access to these works most restricted. And though violence seems to damage society more severely than sex, it is sexual work that is restricted most rigorously.

Though Doll contains violent acts, its restriction was unquestionably earned by its sexual acts and organs. That most of these acts were performed on – and most of the organs belonged to – an object that was inanimate, artificial, non-human seems not to have factored into this judgment. Which I found puzzling. To my perhaps twisted thinking, when it comes to literary sexual stimulation, whether in High Art, like Tropic of Cancer, or Low, like Man With a Maid, the classic formulation requires the female, whether an Ida or an Alice, a Lola or Fannie, be initially resistant, even frightened, before being roused to unbridled, gleeful participation by the Jack or Henry. But Doll is without response or emotion. No matter what is visited upon this plastic hunk, there can be no traditional frisson.

Then I realized that by making Doll a doll, against which men fling themselves for gratification, Colwell has commented about erotica itself. The doll in his panels is, no less than the “real” characters with which she shares them – nor, even, than the “Ida” and “Alice” in their sentences – mere marks of ink on paper. The men from Colwell’s pen, who pleasure themselves with this female substitute are any of us who achieve pleasure by rubbing our imaginations against similar scratchings.

Images are a funny thing. Recently, in the café where I pass my mornings, as part of a group photography exhibit, a side wall held a hanging that had been photo-shopped into a multi-colored distortion. The other photos were of a type customarily displayed: urban street; ice floe; nude woman chastely reclined on a beach. But among the calm, this orange-upon-blue visage – horn-browed, point-eared, eyes red-rimmed hollows, four-fanged mouth a black and gaping hole – shrieked.

Images are a funny thing. Recently, in the café where I pass my mornings, as part of a group photography exhibit, a side wall held a hanging that had been photo-shopped into a multi-colored distortion. The other photos were of a type customarily displayed: urban street; ice floe; nude woman chastely reclined on a beach. But among the calm, this orange-upon-blue visage – horn-browed, point-eared, eyes red-rimmed hollows, four-fanged mouth a black and gaping hole – shrieked.

Each morning, during the exhibit’s run, Aaron (a pseudonym), upon arrival, lifted a sheet of newspaper from the discard rack and taped it across the demon’s face.

“Hey, censorship!” I said, the first time.

“I’m sick,” Aaron said, “I don’t need negative energy.”

Aaron, husky and bearded, maybe fifty, is himself an artist. The cancer, for which he has undergone multiple surgeries has returned – and reached his pancreas. “A death sentence,” one of the cafe’s four Harrys pronounced.

Being a First Amendment absolutist is difficult in the face of Aaron. I do not say, “You don’t have to look.” I do not tear the newspaper down.

But, really, isn’t it the same? There was a time the nude woman would not have been allowed on the wall. (If portions of her anatomy were in contact with portions of another nude someone’s, she would not be there now.) Aren’t there always energies to be feared, flowing from images and words, which will incite the citizenry to violence or sexual frenzy or which well degenerate the race? Aren’t the ADULTS ONLY banners and view-obliterations always for someone’s good? Doesn’t someone always know what’s good for everybody else?

[1] Editions were also published in England, France, Germany, and Italy. Rip Off collected the first three issues in a single volume and Kitchen Sink the last four. (Neither reprinted the fourth issue) Both, like the comics, are lamentably long out-of-print.

[2] Colwell, who has been married for sixteen years, tells me that I have misconstrued Heldrun’s position and that while he remains “tormented” by the question of “whether kindness or cruel domination is the best way to interact with women,” he has not made up his mind. (My wife, after reading this, requested a retraction of her “OY!”)