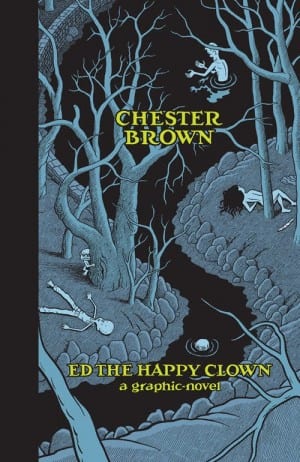

Ed the Happy Clown

Ed the Happy Clown

Chester Brown

(Drawn & Quarterly)

Drawn & Quarterly has sent me unbidden a copy of their handsome new edition of Chester Brown’s Ed the Happy Clown, and the best way to ensure such casting of bread upon the waters will continue is to write something about it. Besides, Ed was one of the first works to annunciate the rebirth of art comics, and twenty-odd years on is a good point to assess how it stands among what it created. At this remove Ed seems to stand as a classic of sophomoric humor. If you take this as praise so faint as to damn, you misunderstand me. What I mean to say is that it is a classic, and the essence of this classic is sophomoric humor. There are few things in life more difficult than to make a legitimate classic out of material normally considered to be dross. Webster’s defines sophomoric as “overconfident of knowledge but poorly informed and immature.” In his explanatory notes Brown recounts with chagrin that many elements of his improvised plots were the result of ignorance or incuriosity about the world. For example, Brown notes that he didn’t realize at the time that sewage disposal was the responsibility of local and not national governments. He draws a Ronald Reagan who looks nothing like Ronald Reagan and a Nancy Reagan who looks like a paperback-cover gun moll in large part because he paid no more attention to our politics than an American pays to Canadian politics. Ed the Happy Clown incorporates such diverse elements as a man whose anus has become an interdimensional portal through which an alternate universe is disposing its excess excrement, a clown who finds that the tip of his penis has been replaced by the tiny head of that alternate universe’s president of the United States, a young woman who becomes a vampire because she died while committing adultery, a race of rat-eating pygmies who have been introduced into the sewer system to combat a plague of rats, a mother and daughter sewer pygmy hunting team, and a police force that dresses like Bucky Barnes out of the Captain America comics. Shock elements tend to lose their charge over time because the shocks depend on contemporary attitudes that are subject to change. Brown’s outrages remain outrageous because he approaches them not with a youthful sense of moral certainty but with the deadpan matter-of-fact detachment of someone who finds the world essentially mysterious. His approach is of one who has not yet passed judgment. Take the scene in which the little man from the alternative world innocently reveals that people where he comes from typically engage in homosexual relations, and the government officials instantly draw weapons and blast him into pieces. To a more callow cartoonist the point would be the contrast between his own enlightened attitude and those of his society. In Ed the humor is in the non sequitur extremity of the reaction. If Brown had put the actual Ronald Reagan’s head on the end of Ed’s penis it would have registered as crude, childish, and heavy-handed. Brown’s instincts instead point up the surrealism of the concept. Thus his imagery retains the surrealist power to unsettle.

The burning question from previous readings of Ed was whether the ending was satisfying, and the answer on rereading is in the affirmative. It has to do with the fate of Josie, the most sympathetic character in the book. In a key subplot, a traumatic experience leads hospital janitor Chet Doodley to conclude that God is telling him to emulate St. Justin, a reformed thief who cut off his own hand, in cutting off the source of his sins. Therefore he cuts the throat of Josie, a woman with whom he’s been having an extramarital affair, while they are copulating. When Josie’s spirit leaves her body, she encounters Annie, the ghost of Chet’s long-dead infant sister, who explains that Josie is not truly dead but, once she returns to her body, will be a vampire because she died while actively engaged in a grievous sin. (If this were the case it would seem there would be a lot more vampires around.) Josie asks if Chet would be similarly condemned if he were to die, and Annie explains that he had subsequently prayed, repented, and been forgiven. Those who die after committing a grievous sin without repenting are lost souls and condemned to the eternal flames. Josie returns to her body, seeks out Chet, seduces him, and after the grievously sinning activity is finished, kills him. She then dies from exposure to sunlight. The last panel leaves her soul condemned to spend eternity in the flames in the arms of Chet.

The liberal view of moral rules is that they are a means to an end, and that end is justice, and perhaps happiness. If the result of application of the moral rules is injustice or unhappiness, then the moral rules are defective and should be amended. The conservative or traditionalist view is that the moral rules were handed down by God and thus must be just. If they do not seem so to us then it is we who are in error, and it’s our duty to understand how they are just. The proposition Brown poses in Ed is, suppose the rules just are. Suppose that the soul is eternally condemned according to these rules in the same way that your hand would be permanently disfigured if it were burned in a fire. Suppose the instrumentality that created the rules either didn’t consider the consequences, or is inscrutable, or was simply indifferent. The conclusion he draws is that it would be terribly sad. The ending gives the story an emotional punch that it wouldn’t otherwise have.

Brown’s career ultimately follows the direction of that ending. For the most part he ceases to pursue humor per se. His comics are neither intentionally humorous nor unintentionally humorous; humor is simply a byproduct. His point of view might well seem more comic to a reader who doesn’t share it than it does to Brown. Interestingly, now that he has developed a coherent political point of view he has resolved the proposition posed by Ed’s ending. He has come to believe that mankind has found in the free enterprise system a way of ordering society that provides individual autonomy and freedom from coercion. The absence of coercion trumps all other values. The rewards this system metes out are the most just and generous possible. A byproduct of this revelation is that he’s come to have an informed opinion about Ronald Reagan, and that is that he’s the best American president since Calvin Coolidge. One detects a certain agenda in this ranking. I really don’t intend to get into the game of beat up on the libertarian heretic. I do note however that in adopting his current posture, he’s disregarded the sadness.

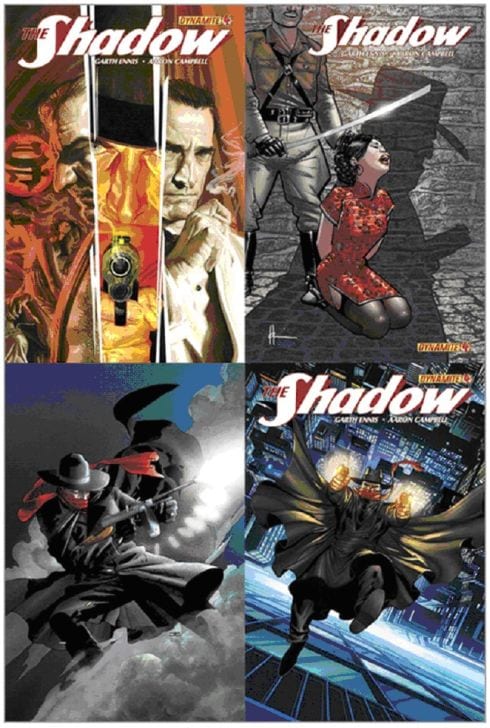

Battle of the Shadow Covers

The Shadow

Garth Ennis and Aaron Campbell

(Dynamite Entertainment)

My official position on variant cover promotions is aristocratic disdain, particularly when practiced as prolifically as by Dynamite Entertainment, a company that will apparently put variant covers on its employee handbook. I must confess however that when those detonators pulled the gag in their version of The Shadow they knew what gullibility lurks in the heart of this man, at least. When it’s done right The Shadow always had a way of getting around my defenses. Tapes of the Orson Welles/Agnes Moorehead radio version had me reacting to broadcast advertising the way you’re intended to for the first time in my life. Notwithstanding that I have never owned a furnace, I wanted to buy Blue Coal. (I mean, if that’s the kind the Shadow likes . . .) Though Dynamite’s Shadow is the Shadow done right -- the best of all comic book Shadows, based on early returns -- that has little to do with the subject at hand, which is the fascination the variant covers have for me.

The prime beneficiaries of the alternate cover come on opposite sides of the consumption spectrum. At one extreme is the collector-loon, who likes nothing more than to have something more to collect. For this buyer Dynamite supplies not only four or five evenly distributed variant cover designs, but God’s own number of hyper-rare “retailer incentive” variants for collectors to war over. On the other end of the spectrum is the buyer of the collected edition, which will contain all the variants as an appendix. For the buyer who wants to read the comics as they come out but will be damned if he’s going to be gulled into buying more than one copy of the same comic book, it becomes a matter of dubious consumer choice. You are called upon to choose how your comic book is going to be decorated in the same way you choose what color car you’re going to drive. Or more charitably, you are promoted to a practical art critic through the act of choosing.

Actually, now that I think of it cartoonists of the Jim Woodring/Adrian Tomine/Chris Ware ilk could make use of the variant cover gambit. They could turn it into a kind of Thematic Apperception Test (TAT to the trade), which if you don’t have a psychiatric dictionary handy is the one where they show the subject ambiguous, emotionally charged pictures in order to evaluate the subject’s thought patterns and emotional responses. You could make variant covers out of TAT images, sell them in shrink wrap (Freudian!), and then the buyer takes it home unwraps it and turns to the diagnosis in the back to see what’s wrong with him. Now it’s true that an actual TAT requires a more detailed response than “I’ll take that one,” but it’s close enough for pop psychology.

For purposes of The Shadow, your alternatives are a simple pulp-or-comics. The toughest competition is appropriately enough issue #1:

Chaykin takes the role of Shadow artist emeritus, either because they couldn’t get Michael Kaluta or because Kaluta would have made the rest of them look sick. In truth, all of the Kaluta covers were better than any of the covers in the Dynamite series so far. The primary reason is that every Kaluta cover told a story. The primary reason for that is that Kaluta had a story handy. The information the Dynamite cover artists seem to have been working from appears to be (a) he’s got a slouch hat, a red scarf and two .45 automatics, and (b) the Japanese are involved. You can imagine the editorial meeting: “It’s The Shadow. What the hell else do you need to know?” The Dynamite covers are primarily mood pieces working from a limited set of themes. These include: the Shadow wears a red scarf, the Shadow has guns, the Shadow shoots his guns, the Shadow shoots his guns while leaping, the Shadow is mysterious, the Shadow towers over the world of crime, the Shadow protects this here girl, the Shadow is surrounded by intrigue, the Shadow for some reason is surrounded by a flock of birds (which must be hell on your satin cape).

For #1, the pulp vs. comics choice is particularly stark. The Alex Ross is pure Street & Smith, and Ross vividly makes it clear that the hero is a malicious motherfucker. Though torn, I wound up going with comics and the Howard Chaykin. I was finally swayed by the dynamism, even if the Shadow did wind up looking a bit more like Mandrake the Murderer. The also-rans were in the Towering Shadow genre, one with birds, one without, illustrating how the force of the hero’s personality can distort perspective.

Pulp was the winner the second time around, though not with Ross but with Jae Lee. Of the five issues worth of covers presently on view Lee gives the best take on the Shadow with guns theme, as if he was saying to his enemies, “I just wanted to let you know how I’m going to look in my coffin, since you’re never going to live to see it, ha ha ha.” Ross has a major falling off with a mood piece intended to show the Shadow firing into a haze of blood but winding up a bloody mess. Chaykin’s damsel in distress number lacks verve, and composition requires that the plane be headed in the wrong direction. Cassaday gives us a peek at the cover of GQ’s Shadow issue, while Rae Sook gives us the moment before the Shadow gets tangled up in that damned scarf.

Based on the thumbnail I’d gotten the impression that Ross was giving us his variation on the Explosion in a Shingle Factory theme, but seen in the flesh at the store that’s the one I picked. Chaykin improves a bit on the damsel in distress theme, showing a bit of the good old Chaykin cynicism by putting the girl in front. Cassaday is working on the theory that the Shadow would be even more menacing in the ugliest color combination known to man. Newcomer Steven Segovia gives us a glimpse of the Shadow’s earlier career as a scarecrow.

We now get to the point where my choices are theoretical rather than actual. Ross it seems couldn't decide which of three pedestrian images to choose, so he gives us all three. For his third damsel in distress Chaykin goes for the normally surefire girl in cheongsam menaced by a Japanese soldier with a samurai sword, but unless the execution is improved in the final I’ll give it a pass, I think. While up to now I’ve been thinking that finding nothing but John Cassaday covers left is a sign you’re getting to the comic shop too late, I think I might be going with him this time. He does after all introduce a new gun. Sean Chen is docked a notch for putting the character in a situation he couldn’t possibly survive. This is one of the ones who doesn’t fly without an airplane, Sean.

Here’s a straight-up Ross/Chaykin showdown with dueling Rising Sun motifs. I’m giving the nod to Ross for taking it one step further with the dripping blood. Besides, I can’t decide whether Chaykin’s Shadow is doing a duck walk down a wall or jumping out of a plane without a parachute. Cassaday demonstrates that the split-image cover doesn’t work diagonally, either. Francesco Francavilla, gun, scarf, hide-and-seek, zzzzzzz.

The man on the spot when the comic is wrapped in high-priced talent like this is the man who does the guts. One of my earliest comics memories are those '60s DC war comics with the covers by Joe Kubert and the insides by someone who was certainly not Joe Kubert, which inspired a lifetime of cynicism. In The Shadow, however, Aaron Campbell barely bats an eye. Your modern comics reader likes his reality, and Campbell’s work does have a distinct air of photo reference, but it still manages to look like comic art rather than fumetti. I know nothing about him, but superficial searching indicates he’s Dynamite’s plainclothes hero specialist (he did their Green Hornet). Indeed, the most awkward moments come from the imperative of getting the hero into the outfit. In #2 Lamont Cranston and Margo Lane are ambushed by Nazi spies on an airplane in flight. Split seconds count, but Cranston still finds time to change into trench coat, scarf, gloves and hat. It’s hard to see the point, since if the Krauts didn’t know to whom the voice of the invisible Shadow belongs his sudden appearance in mid-air must surely have given them a clue. (“Vas ist los? Ve vas tryink to vaste Lamont Cranston und der verdammt Shadow geshowen up!”) If he wasn't going to leave any witnesses, again, what's the point?

What this says about Campbell is that he doesn’t need the costume. But what seals the deal for me is his sense of casting. Lamont Cranston looks like Herbert Marshall with a little Laird Creegar thrown in. Margo Lane suggests Veronica Lake with a little Agnes Moorehead thrown in, as if the former would have been too glamorous and the latter too plain. I don’t know if that’s actually how he got there, but these are 1930s faces, living in a 1930s world.

A hero who acts like a villain – if that doesn’t call for Garth Ennis what does? Ennis is one of those inexhaustible hardboiled writers a la Donald E. Westlake or Lawrence Block who can turn the stuff out in quantities that challenge the market’s capacity to absorb it and yet have the last thousand words no less fresh than the first. The issue with him has always been that while a dish can be too bland it can also be over-spiced. For the first two issues at least his tendency to go over the top is in check. It is after all hard to be out of proportion when the enemy is the Axis, though he does take time to make his villain a pedophile as well. Nobody does ruthless like Garth Ennis. If it were up to me he could keep doing this for as long as he’s done The Boys, and I suppose if he owned it he might, but I understand he’s only signed for six.

Forty Year Time Delay Kitchen Logic

Bringing Up Father: From Sea to Shining Sea

George McManus

(IDW)

If Maggie is this social-climbing would-be grand dame with servants to wait on her hand and foot, why does she always have a rolling pin handy to hit Jiggs with?

Department of Unfair Comparisons

Scenes from an Impending Wedding

Scenes from an Impending Wedding

Adrian Tomine

(Drawn & Quarterly)

Will You Still Love Me if I Wet the Bed?

Liz Prince

(Top Shelf)

I happened to pick these two bits of vicarious happiness up together in the tiny little book table of a local comics shop. The Tomine came out last year, the Prince is copyright 2005, though I don’t suppose she’d mind my reminding you of it. She would probably be less enthusiastic about being compared with a figure from the Mount Rushmore of art comics, but that’s not the sort of comparison I have in mind. Both are in an informal sketchbook style, with the proviso that Tomine when he’s being informal is like Little Richard when he’s being restrained. The Tomine started out as a wedding favor, a very good idea of his bride-to-be which may defray the cost of the wedding. It’s most notable as an opportunity to see Tomine without angst, though he’s careful to put some lemon in the sugar water. The Prince might be called Scenes from an Ongoing Besotting. It’s as if the sexless couple from the Love Is strip suddenly hit puberty and discovered that love was a lot of things they’d never imagined before. It does threaten to cloy, but this quality is leavened by the thought of how operatically sour the thing could have gone in the time since. One difference between Prince and Tomine is that you’ll never catch him expressing emotions he might find embarrassing at a later date.

“I’m Aware of His Work.”

That dismissal and banishment of Ray Bradbury from the ideal science fiction library of The Simpsons’ Martin Prince points up the curious place of the recently deceased in the hearts of many of his readers. Bradbury is a thirteen-year-old’s Shakespeare. In this country at least he is likely to be the first author to awaken a young reader to the notion that there’s such a thing as good writing. He is also likely to be the first favorite writer with which a young reader becomes disenchanted. It’s the contradictory juxtaposition of futuristic elements with nostalgia for the Walt Disney Main Street U.S.A. of sarsaparilla and penny candy at the apothecary, gliders on the porch, and brass band concerts in the park that begin to cloy. The science fiction reader like young Martin who seeks a brave new world where he is not an outcast and a dork comes to realize that Bradbury wrote about the future not because he yearned for it but because he was afraid of it. That he had written nearly all the work he’d be remembered for by 1965 only exacerbated the process of disenchantment. (As time goes on how a reader takes to Bradbury may well depend on whether he starts with the 1965 Vintage Bradbury or the thousand-page doorstop Stories of Ray Bradbury. Not that a kid is likely to pick up the longer book.) To many of us the fiction of Ray Bradbury is a magical land we visited in childhood and will never return to.

His main relevance to comics, aside from the EC adaptations, was his role as ambassador from the world of geekdom. For the longest time the passport for anything from the world of fantastic fiction or comics to the mainstream audience was an introduction by Ray Bradbury. It’s a role that has been largely inherited by Neil Gaiman, which is an interesting development. Bradbury was an ambassador because he’d crossed over; his stories had come to be published in The Saturday Evening Post and McCall’s rather than Weird Tales and Planet Stories. Gaiman on the other hand never crossed over in that way; the mainstream crossed over to him. Art Spiegelman fills the same role for a different kind of comics, but he’s more of a crossover in the Bradbury tradition.