Think back to the mid-1960s, when Marvel Comics first expanded beyond the house that Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko built upon the foundation of the Fantastic Four, Hulk and Spider-Man. Of all the eventual hall-of-famers who joined Marvel – John Buscema, Bill Everett, John Romita, Jim Steranko, George Tuska, even Alex Toth among them – writer/editor Lee forced each of them at first to ‘draw comics the Marvel way.’ Which meant penciling over layouts drawn by Kirby, the de facto house artist, whose storytelling embodied everything Lee wanted Marvel Comics to say.

The lone exception – the one illustrator whose style was so singular, so unconventional, so un-Kirby that Lee never once forced the collaboration -- was Gene Colan. “Gene the Dean” or “Gentleman Gene,” as Stan nicknamed him, joined Marvel in 1965, and his cinematic, “painting with a pencil” approach brought a whole new look to the likes of Sub-Mariner, Iron Man, and Daredevil.

It never would have worked, Colan on Kirby. They were too different. Kirby was about shapes, and Colan was about shadows. Jack’s specialty was in-your-face action; Gene’s was the nuance of human expression. The two artistic sensibilities were so diametrically opposed that even 40 years later, when Colan was offered a once-in-a-lifetime chance to finish a Kirby drawing for a cover of The Jack Kirby Collector magazine, he refused. Not so much because he wouldn’t do it, but because he felt he couldn’t.

“Gene’s style was too unique, too different,” said Lee, when asked why he exempted Colan from the Kirby’s apprenticeship. “It would have handicapped Gene [to draw over Kirby layouts]. He shouldn’t have to draw over anyone else’s layouts because it wouldn’t look like Gene Colan.”

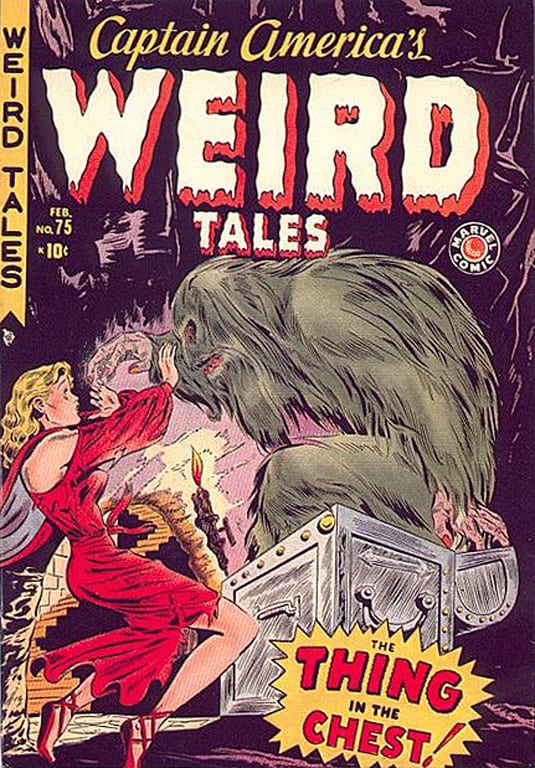

Mind you, Lee felt otherwise in the 1950s, when he was running Marvel’s predecessor, Atlas Comics. Colan worked for Lee then, too, drawing the western, horror and war comics du jour. Then, Colan recalled, Lee asked him to imitate the popular styles of the late Joe Maneely and Tuska. Uncharacteristically, the meek Colan refused. “I said, ‘Stan, if you want me to draw like George Tuska, then get George Tuska to draw it. I’m not George Tuska.’”

Indeed, Gene Colan never would be mistaken for anything less than what he was: One of comics’ unique stylists. He wielded his pencil like a brush to capture the toned subtleties of action, emotion and lighting. He brought a cinematographer’s vision to comics storytelling, and his stories were instantly recognized by fans, treasured by scholars and appreciated enviously by even his most accomplished peers.

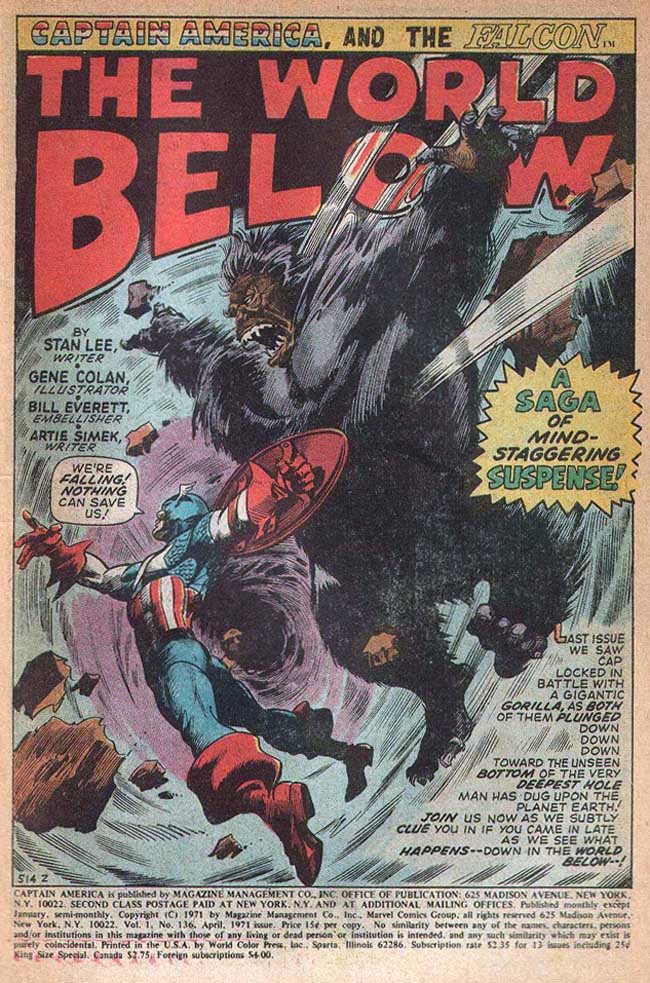

While delighting his fans, Colan often frustrated his writers. He was notorious for never reading scripts in advance, so he often ran out of pages before drawing the end of the story. Meanwhile, he would devote half a page to a hand turning a doorknob, or three pages to Captain America merely walking down a street. His indulgences were accepted in the 1960s, when Lee put the artists in charge of pacing the stories. But Colan encountered resistance in the 1970s, when the writers gained influence, and especially in the 1980s, when the editors seized control.

Ultimately, he outgrew his inkers, who always struggled to delineate Colan’s complex penciled drawings. By the 1980s, Colan’s penciling style and printing technology were so refined that, starting with Dean Mullaney at Eclipse Comics, publishers skipped the traditional inking stage and started reproducing Colan’s textured work straight from his pencils, starting with writer Don McGregor’s Ragamuffins and Nathaniel Dusk. Once Mullaney opened this door, printing from Colan’s pencils became the default for the next 20-plus years. Even at the end of his career – Colan’s final feature-length story was a 2009 issue of Captain America – Marvel produced two editions, one in color and the other in black-and-white, so fans could appreciate the pure beauty of Colan’s pencils.

No one could or likely ever will draw quite like Gene Colan.

But he was unique for more than his body of work. Colan’s 2005 biography was entitled “Secrets in the Shadows,” and on one level it described the art. But the book also explored the man, who battled his own secrets and shadows.

He was hyper-sensitive. If Lee and Kirby were the Lennon & McCartney of Marvel Comics, then Colan was the Brian Wilson – a tortured genius who battled his own emotions and the influence of others. He was the type of person who could pick out and be deflated by the one negative vibe in a roomful of avid supporters. This sensitivity, which enhanced his work, also left him susceptible to strong-willed people. Throughout his career, Colan felt bullied by some of the industry’s biggest personalities, including Harvey Kurtzman, Bob Kanigher and Jim Shooter.

He over-worked. Colan’s ambitions and lifestyle were always a step ahead of his income, and so for decades, like many of his peers, he worked long hours to churn out pages at the expense of his own family. While generations grew up under the influence of Gene Colan comics, he rarely saw his own four children -- a sacrifice he later spoke of with deep regret.

And, like his signature character, Daredevil, he was vision-impaired. In the latter third of his life, Colan was so stricken by glaucoma that he was virtually blind in one eye and reduced to tunnel vision in the other. He underwent numerous medical procedures and daily routines to retain just enough vision so he could continue to draw.

Yet despite these struggles, Colan forged an unprecedented career. He worked in comics for parts of seven decades, from the 1940s to the 2000s – a feat matched only by the likes of Will Eisner and Joe Kubert. His creative range is unmatched – he literally drew everything, from Archie comics to Wonder Woman, leaving his mark on such popular characters as Batman, Captain Marvel and Dracula, cult favorites like Howard the Duck, Dr. Strange and Night Force, as well as more esoteric, personal works including Ragamuffins and Nathaniel Dusk.

He is best known for his long run on Daredevil in the 1960s, but Colan’s most critically acclaimed work was his 70-issue Tomb of Dracula in the 1970s (where he co-created the vampire slayer Blade). Pressed, he said his favorite work was the private eye Dusk in the 1980s. In fact, for many years the only artwork Colan displayed in his own house was a three-page Coney Island chase sequence from the second Dusk miniseries.

Colan also was one of comics most accessible creators. An Internet pioneer among comic book artists, he sold his original artwork online and established a fan chat group in the late 1990s. Through these efforts, led by his wife Adrienne, his staunchest champion until her 2010 death, Colan befriended scores of his most ardent fans worldwide, becoming an avuncular figure to his readers and their families. Over the last decade or so of his life, Colan got to see first-hand what became of all those children who grew up reading his work.

“I still find it almost impossible to believe that there are people who are so interested in comics, and in what I’ve done,” Colan reflected in 2005. “There are so many artists out there that are just as good – some even better. For me, it’s a ride that didn’t enter my mind would ever happen. I just got into the business as a way of entertaining.”

Early Years

Eugene Jules Colan was born in the Bronx, NY, on Sept. 1, 1926, the only child of Harold and Winifred Levy Colan.

An introvert, Colan lived vicariously through the comic strips – Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates and Coulton Waugh’s Dickie Dare were his favorites – and he loved nothing more than to create his own comics. “I drew a lot -- I was always drawing,” Colan said. “My biggest joy was to be sick in bed, so I wouldn’t have to go to school or any of those things, and I would plan out my day to just draw pictures, pictures, pictures.”

Film also was a huge influence, and even as a young boy Colan was fascinated by how directors staged their scenes. In his townhouse he would walk slowly from room to room holding his father’s box camera – the type you’d look down into to preview your photo – and he’d frame his environment like he would a film.

No film influenced Colan more than the original Frankenstein, which he first saw at age five. Colan was terrified by Boris Karloff as the monster. After that fright, Colan couldn’t purge the monster from his memory. Instead, he responded the only way he knew. “I decided that I would create a monster of my own, so I got out big sheets of paper – I was creative in that respect – and I drew one” – the birth of Colan as a horror artist.

At 14, Colan gathered samples and visited DC Comics. The editors were impressed and invited him to meet Batman creator Bob Kane. After high school graduation in 1944, Colan scored a summer job as an artist at Fiction House, publisher of titles such as Wings, Rangers and Fight. There he was mentored by the likes of Tuska, Murphy Anderson and Lee Elias.

In early 1945 Colan enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Force. The war in Europe ended before Colan even got to basic training, so he was shipped to a base in Manila. In the Philippines, Colan fell under the tutelage of illustrator Steven Kidd, who published in Life and other major magazines. Kidd specialized in military illustration and eventually became the official U.S. war artist assigned to Korea. “He was a great eye-opener to me,” Colan recalled. “One time he asked me to draw a tree. I did it in 10 minutes, and he says to me ‘It took God 100 years to make a tree; you can’t sit down and make one in 10 minutes!’

After discharge, Colan enrolled in the Art Students League of New York. Then, in 1947, Colan decided to visit Timely Comics, Marvel’s earliest incarnation and the publisher of Captain America, Human Torch and Sub-Mariner. He was ushered in to meet the editor. “I walked into this office, and there was Stan Lee, playing cards and wearing this beanie cap with a propeller on it! Stan was boyish, very charming. He says to me, ‘So, you want to be in comics, eh? Sit down!’”

Struggles

Colan joined the Timely bullpen and enjoyed an initial period of success, drawing superhero and genre comics alongside mentors such as Mike Sekowsky and Syd Shores. He also met some fellow up-and-comers, including John Romita, who went on to distinguish himself as Spider-Man’s main artist and Marvel’s art director in the 1960s and '70s.

“I knew his work before I ever connected it to his face,” Romita once said of Colan. “He amazed me. He did a couple of South Pacific war stories with pilots. I remember one in particular: he did a panel – I’m talking 1949, 1950 – he did an aerial shot of a plane crash landing in the ocean, and he did the whole thing black with just a little splash. And I was amazed. I remember saying ‘I don’t have the guts to do that!’ But he made it believable.”

The good times were short-lived, though, as Colan was laid off during a 1950 market crash and forced to freelance. During this period, he had his initial run-ins with strong-willed editors who nearly chased him out of the business. The first was Harvey Kurtzman, who edited Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat at EC Comics. Kurtzman was demanding of his artists, and he didn’t like how Colan drew his one and only assignment, the story “Wake” in issue #30. Soon after, Kurtzman was hospitalized for exhaustion, and Colan – who desperately wanted to join the distinguished EC stable of artists - dutifully visited. Kurtzman snubbed him. “He looked at me and said ‘You’re the perfect dupe,’” Colan said. Kurtzman wasn’t necessarily wrong – Colan was naive. But Kurtzman offended the artist. “He was kind of nasty about it,” Colan says. “He was not someone I wanted to continue with, so I didn’t.”

Colan’s next tormentor was Bob Kanigher, DC’s prolific and mercurial writer, best known for co-creating Sgt. Rock. Kanigher hired Colan to draw war, western and romance stories, and he browbeat the young artist with his untempered criticism. Kanigher’s complaints ranged from storytelling to rendering, and they were always delivered harshly. Finally, in 1957, Colan fought back. “One day I told him ‘Y’know, you’re crazy,’” Colan recalls. “Julie Schwartz, his desk was back-to-back with Kanigher, and he heard me. Kanigher said ‘Julie, did you hear what he said? I’m crazy.’ I said ‘yeah, you’re crazy.’ Oh, I wanted to throw him out the window.” Instead, Colan got thrown out of the office – fired from his DC assignments (the biggest of which was western hero Hopalong Cassidy), and his comics career all but evaporated. Until he reunited with Stan Lee.

Swinging into the ‘60s

The early 1960s were the most tumultuous period of Colan’s life. He was recently divorced from his first wife, Sallee, estranged from his two young daughters, Valerie and Jill, and he was unable to find work in comics. Instead, he ended up in a dead-end job drawing educational filmstrips.

Then he met the woman who changed his life. Adrienne Gail Brickman was 19 years old when Colan met her at a singles resort in the Poconos. The two were instantly attracted, and their romance quickly blossomed into marriage on Valentine’s Day 1963.

From the outset, the outspoken Adrienne was Colan’s biggest advocate, and she soon convinced him he had to quit his job and get back into comics. “She said to me ‘You’ve got to get out of here,’ so easy like that,” Colan later recalled. “‘To work without artistic challenge will destroy your soul, your passion for life,’ she said. And I said ‘Go where?’”

But Colan’s departure coincided with a comics resurgence, and he was able to pick up work at DC, Dell and even Marvel, where he drew an occasional science fiction or western story. By 1965, business was booming, and Lee asked Colan to quit his other assignments (including gorgeous black-and-white wash jobs for Warren’s Eerie and Creepy horror magazines) and work fulltime for Marvel. At first, Colan resisted – he didn’t dare commit to a single publisher – and so his initial Marvel superhero assignments, Sub-Mariner and Iron Man, were signed with the pseudonym “Adam Austin,” so as not to tip off his other accounts about his freelancing. But two things quickly became apparent: 1) Marvel was solid, and 2) There was no disguising Colan’s artwork. By the time he took over Daredevil with issue #20, he was signing his own name, working exclusively for Marvel and embarking on one of the happiest periods of his career.

With Daredevil – his first feature-length superhero assignment – Colan had everything he wanted: a lantern-jawed lead character, a diverse cast of co-stars, a colorful rogues gallery, New York City as a setting … and 20 pages per month to tell stories the way he felt they should be told. “The fact that he was blind and could do all these things really appealed to me,” Colan said of his stint on the title. “I tried to figure out a way to actually illustrate his blindness so that the reader could follow it. He had an uncanny knack of actually seeing better than a sighted person because of his keen senses, and I tried to illustrate that in some vague way with pictures of what he saw. Strictly out of my imagination.” That imagination led to an almost-uninterrupted 80-issue run on Daredevil, which forever became associated with Colan.

Lee was Colan’s primary writer at Marvel in the '60s, and he worked to Colan’s strengths by giving him just the barest bones of plot for each issue’s story. Lee simply didn’t have the time to write a full script and Colan didn’t have the patience to read one. Instead, he would sit down and draw each individual page, breaking up the pace here and there with a full-page splash. Frequently, however, he’d reach the end of the story and discover that he’d run out of pages before he ran out of plot, so he’d have to either continue the story or cram the conclusion into a jumble of panels on the final page.

Roy Thomas, Lee’s assistant editor in the 1960s, remembers this problem: “I remember [Stan] got a little upset once and called Gene up and said ‘Well, didn’t you see this was coming up?’ And Gene said ‘Well, y’know I don’t read the plot until I get to that page.’ I guess Gene liked to read it at the same pace as a reader would. Stan liked it, but that kind of thing was atypical of other artists, so it would drive him a little nuts. He always liked the end result, but sometime it took a little extra work.”

What might have been “extra work” for Lee was backbreaking work for Colan, who pushed himself to draw two pages per day, seven days per week – the equivalent of three feature-length comics per month. The pace wreaked havoc on his home life, which now included children Nanci and Erik, both born in the early '60s. During that frantic era Colan also drew Captain America (for which co-created the African-American superhero, the Falcon), Captain Marvel, Dr. Strange, among others. But as fantastic as the concepts grew, Colan still brought them back to earth with his unique touch.

Dracula and the Duck

In 1971, after more than a five-year run on Daredevil, Colan was bored. He wanted a new challenge. So when he heard Marvel was creating a new comic magazine about Dracula, the lord of the vampires, he wanted the assignment.

According to Colan, Lee assigned Dracula to him, but soon forgot and then offered the same job to Sub-Mariner creator Bill Everett. Colan was devastated. But Adrienne wasn’t. Inspired by stories about Marlon Brando's auditions, Adrienne urged Gene to try-out for Dracula. Colan drew a pencil, ink and wash character study of a raven-haired, bearded Dracula, including a portrait of the Count, and a montage of the vampire king in different poses. “I sent [the montage] to Stan, and the next day he called and said only ‘You got it!’” Colan says. “That was it!”

“It” turned out to be a seven-year, uninterrupted run on the 70-issue Tomb of Dracula comic book. It was not just one of the best horror comics of the 1970s, but one of the decade’s best comics, period. Written for most of its series by Marv Wolfman and inked by Tom Palmer, Colan’s most frequent and best inker, Tomb of Dracula featured a rich ensemble cast, rich plots and moody artwork that set a high bar for mainstream comics.

In the mid-70s, Colan was assigned a title that couldn’t have been any different than Dracula – Howard the Duck, the wise-cracking, cigar-smoking culture critic created by writer Steve Gerber. Artists Frank Brunner and John Buscema drew the first three issues of the comic, but then with issue #4 the series was assigned to Colan, who initially thought he was being demoted to drawing a funny-animal comic for children. But quickly he came to appreciate the mature social satire of the book, and he fit right in with Gerber. “I enjoyed it, because Howard was the easiest thing to do, and it was such a chance to make things funny and lighten up a little bit,” Colan said. “I enjoyed humor, and Steve [Gerber] was so funny. I’d just sit there and laugh my head off just reading the script, and I’d call him and say so.”

The Dracula and Duck comics were both cancelled in 1979. The titles were briefly resurrected as black-and-white magazines, but soon ceased publishing for good, leaving Colan without a steady assignment. But instead of getting a new title, Colan soon found himself fighting for his career.

Out at Marvel, In at DC

Following his promotion to publisher in 1972, Stan Lee effectively retired from comics scripting. The new generation of writers asserted more control over their stories, and several of them balked at Colan’s idiosyncrasies. When writer Jim Shooter became Marvel’s editor-in-chief in the late ‘70s, the tension between Colan and the younger authors came to a head. By 1980, Shooter and Colan were totally at odds with one another over Colan’s approach to storytelling.

“It wasn’t just me,” Shooter once said about the conflict. “The writers he was working with, with the exception of Marv on Tomb of Dracula, they would be coming to me out of their minds because they had written a plot, and [Colan] had kind of ignored it and drawn a lot of big, easy pictures, then 16 panels on the last page. I tried to talk to him, and occasionally asked him to redraw things. Because he was Gene Colan, I would pay him to redraw things. I’d say, “Gene, I’ll pay you to do this, but you’ve got to stop [cutting corners].” In Shooter, Colan saw ghosts of Harvey Kurtzman and Bob Kanigher – but worse.

“[Shooter] was harassing the life out of me. I couldn’t make a living,” Colan said. “He frightened me, he really did. He upset me so bad I couldn’t function.” Just as she had urged Colan to quit one job the 1960s, wife Adrienne begged him to leave Marvel in 1980. After delivering his resignation, Colan was asked to sit down and seek resolution with Shooter and publisher Mike Hobson. Colan agreed to the meeting, but declined any overtures to stay at Marvel. "Shooter was in the same room," Colan recalled, "and I said, 'That man’s not gonna change. He is what he is. Whether it’s six days, six months or six years, it’s not going to be any different, so I’m not going to put up with it for another minute.'"

Colan immediately signed a contract with rival publisher DC, which gave him plumb assignments: Batman, a Wonder Woman makeover, a Superman miniseries, and a new horror title, Night Force, in collaboration with his Tomb of Dracula partner, Marv Wolfman. But Colan’s DC honeymoon was short-lived. Editor Dick Giordano felt Colan’s style lacked the commercial appeal of fan favorites such as George Perez and Keith Giffen. When Colan’s contract expired, the high-profile assignments vanished, and he had a hard time getting work at all from DC.

On His Own

With Shooter gone from Marvel, Colan picked up some assignments there, most notably a long Black Panther serial written by Don McGregor and a Tomb of Dracula revival with Wolfman. He also drew a good number of stories for – of all places --Archie Comics, where he was able to explore a more cartoony style.

But at the same time, Colan, now in his 60s, encountered serious health issues. First came a heart attack, then came a long series of vision problems attributed to glaucoma. After a series of operations to both eyes, he was left with virtually no vision in his left eye, and only tunnel vision in his right.

When word of Colan’s ailments got out, Clifford Meth, a writer and longtime fan, stepped forward to organize fundraising efforts for the Colans. First was an art auction that raised funds to help defray the Colans’ medical expenses. Next came the publication of “The Gene Colan Treasury,” a book written by Meth and produced by Aardwolf Publishing (a company Meth cofounded).

Back on his feet, Colan started to teach art and he continued to freelance, picking up work from Dark Horse (an Aliens pastiche) and Marvel (including a brief return to Daredevil). But by the mid-to-late '90s, when he undertook a new Dracula project with Wolfman at Dark Horse, Colan was starting to mull retirement and thought he might slip away and be forgotten by fans.

Then he discovered the Internet.

Rebirth and Recognition

The Colans first ventured online in 1998, when fan Kevin Hall created their website, www.genecolan.com, began selling original Colan comic book artwork on eBay, and created what became a Yahoo Groups list (http://groups.yahoo.com/group/genecolan/) dedicated to Gene’s life and work. Through Hall’s efforts, the Colans found a new outlet not just for selling Gene’s originals, but for accepting new commission assignments. The commission orders, in fact, came in at such a pace that Colan often said “I’m busier now than I ever was on my best day in comics!”

But more than income, the Internet brought Colan a new level of recognition. By connecting with generations of his fans worldwide, he was able to learn what became of all those children who grew up reading his work. They became doctors, writers, teachers, painters – professionals in their own right who interacted with the Colans daily and continually reminded Gene of the significance and influence of his work.

Suddenly, the Colans had a new virtual family of scores of fans worldwide. The energy of this group revitalized Colan, who remained productive, drawing commissions and new comics projects well into the new millennium. And with greater visibility came new recognition.

*In 2001, Colan fans Kevin Hall, Dominic Milano and Marc Svensson worked with writer Mark Evanier to stage a 75th birthday party for Colan at the annual Comic-Con International in San Diego, and they also put together a documentary film including Evanier’s panel discussion and tributes from such creators as Stan Lee, Neal Adams and Harlan Ellison.

*In 2005, at the annual Eisner Awards, Colan was inducted into the Hall of Fame.

*In 2008, at the behest of writer Glen Gold and curator Andrew Farago, the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco dedicated a major months-long exhibit to Colan and his work.

*And in 2010, Colan’s last feature-length comics work, Captain America #601 –- a story set in World War II and reproduced straight from Colan’s penciled artwork -- won the Eisner Award for “Best Single Issue.”

But Colan’s health also failed in his later years, owing mainly to a damaged liver and cancer. Most devastating personally to Colan was the sudden death of Adrienne after a series of personal struggles in the summer of 2010. In his last year, Colan was looked after by his children Nanci and Erik, and his business affairs were managed by Clifford Meth.

Remembering Colan

Over the course of seven decades in comics, Colan had the opportunity to work with scores of great writers, inkers and editors. Their insights capture Colan’s place in comics history.

“Gene was interested in people and in characters and their expressions, the way they moved,” said Stan Lee. “I always felt the stories he did were very personal. You always got to know the characters and care about them. There was also a great sense of design in Gene’s work. Each page was meticulously designed. Where some artists would do just panel by panel, I always got the sense that in the back of Gene’s mind the page was a canvas.”

“His pencils are subtle,” said Tom Palmer, the inker most associated with Colan’s work. “They may not look that way – they may look very powerful – but if you look at his penciled pages, you see there’s very light rendering, a grey. Now, you typically have three distinct values in these pencils: light, medium and dark. Some [inkers] ignore the light and make the medium as black as the dark, but I saw all three values. That was the difference.”

Roy Thomas, the writer/editor/historian perhaps had the best perspective on Colan’s place in the comic art pantheon. “He had the dynamics of Kirby, but the realism of some of the comic strip artists – the things that people liked later in Neal Adams and other artists,” Thomas said. “Maybe Gene was kind of a transitional figure between Kirby and Neal Adams – two of the great influences. Mainly, he just told a lot of good stories.”