Sometime in 2012, I was on the phone with Geneviève Castrée talking about drawing, and how you can get a stiff neck from doing a lot of it, and she asked me whether, when I was drawing, my nose ever touched the top of my pen. The answer, for me was “Definitely not, and seriously, Geneviève, that’s not normal! Are you taking breaks to stretch?”

Anyone who has had a good look at Geneviève’s originals might not be surprised to learn that she was peering in so intensely as she worked. Her lines are perfect, exquisite, and minute. She often worked at nearly the same size at which her work would be printed, which is to say: small. The level of detail is astounding. Her drawings are little wonders. The best artists are like great athletes in that they make what they do look easy. You watch Serena Williams play tennis or Luan Oliveira skate a ledge and it looks so fluid, it feels in your bones like, yes, of course, I could do that, too. And if you try, you find out that it’s a delusion, that it actually took ten thousand hours of practice. It took inhabiting a particular body and mind in a particular place and time in the world. It’s from tracing certain motions every day for years, weaving a path through and between the artists that inspired you as a kid and the colleagues who excite you as a working artist. That feeling of effortlessness is a smokescreen, and even, in a way, a raised middle finger, to the immense amount of time and luck that it takes to get that good. I felt this very keenly when, after Geneviève died of pancreatic cancer in 2016, I sat down to finish my friend’s last book myself. It looked easy. I could feel the movement in my bones. But actually getting it down on paper was far from simple.

Geneviève had been ill for about eighteen months when she died. I knew she was occupying herself with various small projects. She would tell people she wasn’t working, she said she didn’t want to answer the question. She’d say that she was focused on getting well. But every time I went to visit her at her home in Anacortes, Washington, there were little piles of drawings or embroideries on the table next to the couch, on which she spent her days. And it turned out that in the last several weeks that work became more focused. Two days before her death, she sent me a photo of an unfinished drawing for that book, with the accompanying text: “I don’t like to share things before they are finished, but here is what I am doing with my days (while not gasping for air).”

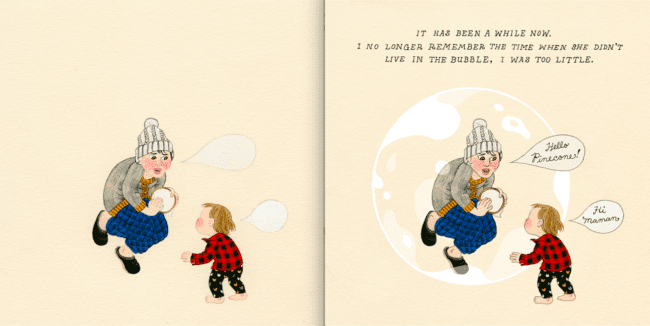

The drawings were for a simple and sweet short story about a young child whose mother lives inside a bubble, a parable about her own illness and recent motherhood, and a beautiful, agonizing meditation on hope. A week later, I was at her funeral. I told her husband Phil that if there was anything I could do to help get her work out into the world, I wanted to do it. He had a ready reply: he wanted me to help finish the book. The drawings of the characters, mainly the mother and child, were perhaps 95% complete, missing only a few lines here and there, and in several places Geneviève’s own un-filled-in black hair. The characters’ clothing was all meticulously rendered in pattern and style, every garment an actual piece worn by either Geneviève herself or her daughter. She had been engaging in the most focused and careful observation of the once mundane details of her everyday life, just as that life was slowly becoming impossible. The little bit of scenery, pulled from the daughter’s description of a walk in the woods, was similarly stunning. But she’d never gotten to the lettering, and the bubbles themselves – a major feature of nearly every scene – were missing entirely.

Phil and I talked about how to go about the project and I started turning the idea over in my mind. While she hadn’t yet drawn the finished bubbles, she had done some rough preparatory sketches in colored pencil.

Between these and what felt like a clear image in my mind’s eye of how Genevieve would draw such a thing, I started working, intending to simply mimic her style as closely as I possibly could.

I couldn’t. I tried painting them in gouache, I tried colored pencil, I tried drawing digitally in photoshop. It felt as though I was drifting further from the goal with every attempt. They at once failed to blend in with her own line and color, and also seemed to loom clumsily over it like a drunk uncle.

I draw things badly in my own comics all the time, and it feels extremely uncomfortable. Getting Geneviève’s bubbles wrong in this particular book felt worse than criminal. Trying endlessly to redo and adjust was getting me nowhere. In talking it over with my partner I was convinced to stop trying to mimic Geneviève’s hand and instead make the bubbles as simple and unobtrusive as I could manage without undermining their narrative function.

It’s often the case that the right solution to a narrative or visual problem feels like it comes out of nowhere. These bubble don’t feel, to me, like "my style," but they immediately felt right somehow. They aren’t her style either, they are simply what the book asked for, and finally accepted. I very much like that they are, in a way, not a drawing I’ve done on top of hers, but, because they are a literal digital negation of the toothy yellow paper on which she drew, the bubbles manage, in a funny way, to end up behind her work, as a support. At least I hope that’s how it feels to the reader. White is a color of blankness, is the color of an empty page, and of course, of death.

Once I stopped trying to mimic Genevieve’s hand, everything I did on the book was digital. I never marked her originals. I also have been asked whether I had a hand in the writing. I did not. I lettered her narration and dialogue, trying again to get close to her style, with perhaps a little more success.

If Geneviève had lived, this little book would look very different. I wish it did. Like many artists I have occasionally considered what would happen to my unfinished work if I died or was unable to complete it. In early conversations about A Bubble, Phil and I discussed whether he should just publish the book as she left it, with pieces undone. The logic is compelling as there is a sense in which it would be more honest. But there is a difference between an artist’s work and the history of their work. One is art, and the other is, in a sense, anthropology. Many readers would surely be interested in Geneviève’s book in whatever stage it was suspended. But she was an artist. She wanted her work read as art in itself, not only as evidence her own life and its untimely close. Not as an artifact. She wanted to draw her readers into the story as she designed it, not as the fates uncaringly decided to measure it out and cut it off. It was a story that she was so compelled to tell that she refused to stop working even though as she was literally gasping for breath. And against the headwinds of fortune’s cruelty, she managed to get it close enough to the finish line that someone could come along and push it across.

Despite its circumstances, A Bubble remains, to me, a most compelling meditation on hope and a laughing poke in the eye of the reaper. Like Geneviève’s best known work, Susceptible, A Bubble is written from the point of view of a daughter, in large part about her mother. In the first book Geneviève is the daughter, in the second she is the mother. While the making of A Bubble was both spurred and impeded by illness, Susceptible was a different kind of struggle to make – it is one daughter’s detailed excavation of a troubled past with a mother from whom the author was, at the time of its making, estranged, and about whom she was ambivalent at best. At the time, I happened also to be working on a somewhat fraught memoir, and we had a number of conversations about the personal and emotional consequences of letting demons out of their boxes and into our books. They were not easy conversations. A few years later, however, after Geneviève had a daughter of her own and was shortly thereafter diagnosed with a likely terminal illness, Castrée and her own mother reconciled. It’s not difficult to regard A Bubble as a kind of return to and rethinking of the themes of the earlier book.

A good share of Geneviève Castree’s work was passionately angry. There is, of course, much in the world to be angry about if one is paying very much attention. She made a book and record about the Iraq war in the mid '00s. She had lots to say about the injustices of gender and of cultural imperialism. She was also a regular practitioner of infectious delight. I remember in particular one very late night during the Pierre Fieulle Ciseaux comics residency in Minneapolis in 2013, when she paused from bleary-eyed drawing to conduct impromptu absurdist interviews with her fellow residents before the streaming camera for an internet audience numbering in the low single digits, giggling uproariously all the while.

For me, A Bubble makes a kind of perfect, triumphant coda to the dance of Geneviève Castrée’s comics oevre. She was staring down the barrel of an impossibly unjust end, and she chose to make a book about paying deep attention to the everyday, and, finally, about escaping any constraint on happiness and connection. I would have helped midwife any work she left behind, but A Bubble feels to me like the worthiest of last words from one of the most brilliant comics talents of the century so far.