John Smith should have been a bigger name. It was the turn of the '90s, and if there was one thing American comics couldn’t get enough of, it was British guys who read a lot of William Burroughs growing up (or at least could give that impression). Smith had all the right credentials: he'd honed his craft writing for that venerable institute, 2000 AD, where his typewriter had helped give birth to offbeat serials such as Tyranny Rex and Indigo Prime. His writing had the right mix for the era of leftist politics and metafictional cosmology. He didn’t just use his caption boxes to express plot points, he used them to express emotions in the form of cut-up poetry. He started opaque, and grew moreso.

Yet while colleagues such as Grant Morrison, Alan Moore, Peter Milligan -- even Alan Grant -- went from one success to another in revamping American creations, a trend which continues to this day with Al Ewing and Si Spurrier, Smith never quite made the breakthrough. His DC Comics credits are a rather sad sight: one issue of Hellblazer (#51) and eight issues of Scarab, a miniseries that's never even gotten the dignity of a collection.

Reading Scarab -- full sets are not that hard to find -- one can understand Vertigo’s reluctance at publishing more from the same writer. What began as a pitch for a darker, edgier take on Doctor Fate doesn’t quite follow the path set up by Swamp Thing or Animal Man or even The Sandman. Oh, there are traces of what we'd come to ‘expect’ from a Vertigo revival by then. There’s a notional longform story arc, following an aging superhero given back his youth, only to lose his wife; there are issue-by-issue ‘challenges’ to overcome. But the story often cares more about the challenges than Scarab himself, who sometimes plays a silent witness, and sometimes seems completely incidental to the plot at large.

The miniseries ends with a fantastically in-your-face deus ex machina, in which two new characters show up and close all the loose ends, while John Smith raises a metaphorical middle finger to the editors who forced him to compromise. For all their famed opacity on series like Doom Patrol and the more metafictional parts of Animal Man, Grant Morrison knew how to play the commercial game. Smith didn’t, or preferred not to learn.

Not that his profile on the other side of the ocean is that much higher. For a man with almost 40 years’ worth of a career in a magazine that is notable for eating up material, Smith has written fairly little. In that sacred text, Thrill-Power Overload, 2000 AD editor Matt Smith describes the process of receiving a John Smith story so that you can almost imagine the forced smile: “As is often the case with John, it takes a while for the scripts to come in, and the story tends to grow in the telling.” While other creators prefer to milk a popular idea as long as they can, Smith genuinely does appear to follow his muse alone, which makes him an odd duck. Speaking to Grant Goggans of one his more popular features, the reality hopping Indigo Prime, which stopped appearing for a good long while just as it was getting traction, Smith mused: “After creating the back story and all those characters I just kind of lost interest in the whole set-up and eventually moved on to other stuff.”

Interviews are another thing Smith does not do often. You can find plenty of interviews with Moore and Morrison and Milligan. These people weren’t just crafting comics; they were crafting an image of themselves (even if unwillingly) - an image that was sold to the audience as much as the work itself. In some cases, the identity became the work (looking at you Animal Man). John Smith, comparatively, is the quiet man. Most of the quotes I found are from the aforementioned 2000 AD history book, Thrill-Power Overload, and the above-linked (short) interview online. As far the 21st century goes, Smith seems to keep to himself, letting the work do the talking.

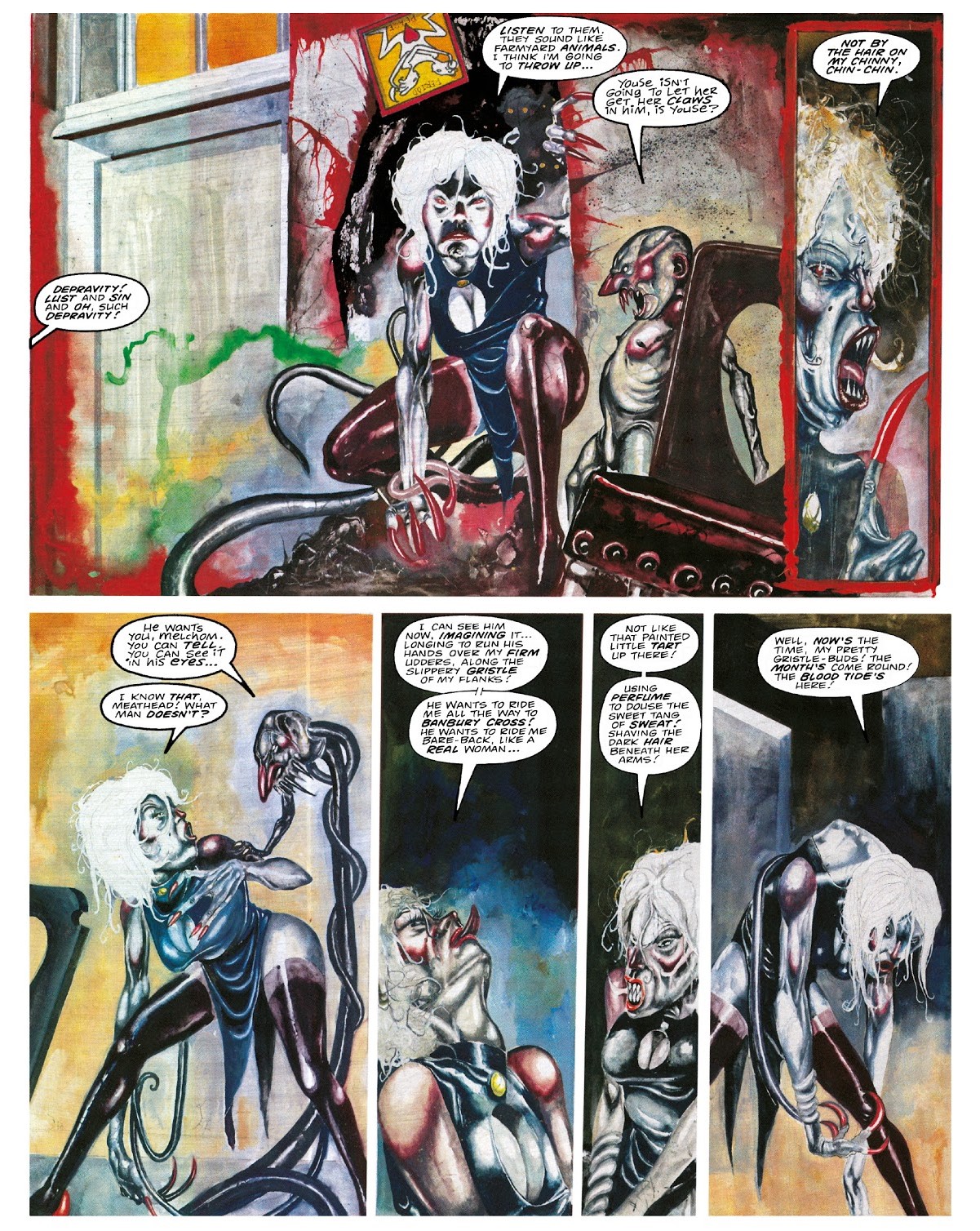

What does the work say though? The reason for this piece is the republication, sadly in digital version only, of Revere. Written by Smith, drawn by Simon Harrison, and lettered by Annie Parkhouse & Jack Potter, it symbolizes everything that John Smith has to offer to the reader, for both good and ill. Serialized across three ‘books’, it tells the story of the titular ‘Witch Boy of London’ as he travels about a post-apocalyptic reality searching for... something. Possibly enlightenment, possibly sex - likely a bit of both.

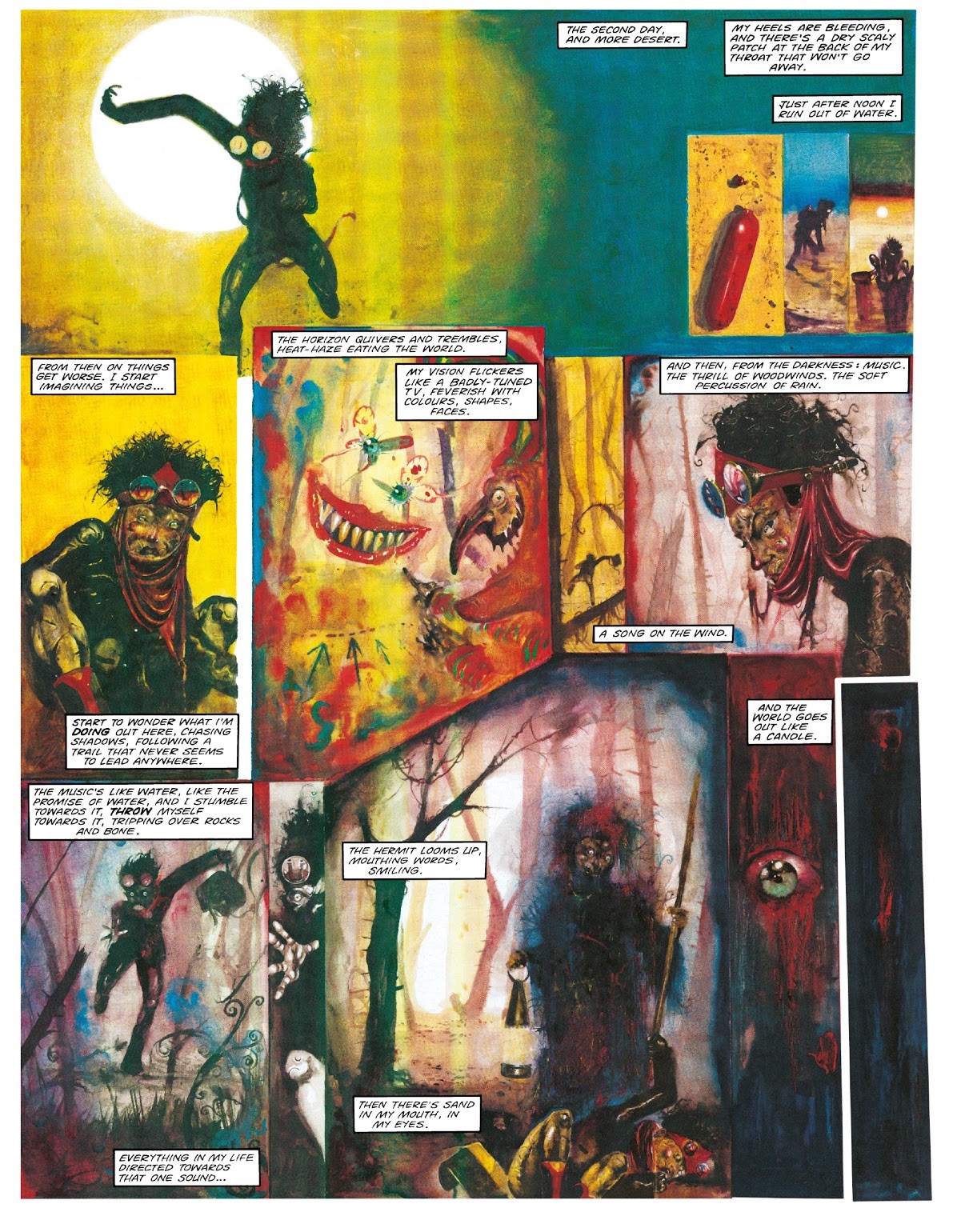

It’s a 1990s feature from 2000 AD, which means it has to be painted; but unlike most post-Simon Bisley works, Harrison is moving away from Heavy Metal-inspired visions of bulging muscles and hyper-violence into realms of drone. The colors are all washed-out reds in the early scenes: a dying desert world that makes London looks like something from a Kyuss album cover. The figures likewise stretch and contour in impossible fashions; bodies twist and faces scream their emotions at the reader. This is a post-apocalyptic world, but not like those of Judge Dredd or Rogue Trooper. This world isn’t a war zone, it’s a zone blasted away from reality - from all the rules of logic.

As Revere astral-projects himself across the city, we get image snaps and text descriptions that could have come from a more ‘typical’ 2000 AD story. There’s even an evil totalitarian police force, dressed in uniforms borrowed from Death Race 2000 (one of the original inspirations for Judge Dredd), but Revere floats above them – as if promising the reader that yes, he knows all that stuff they love to hear, but he’s not very interested in telling it. Instead, the story becomes about Revere transcending the regular world, transcending all this familiar commercial fluff that surrounds him, and becoming this reborn entity. He does it by committing a Leap of Faith, which is a way for the comics to say – ‘I know it all seems weird and impossible, but trust me!’

Does it earn back that trust? That’s up to any individual reader. All this cosmic jumping around, the talk about sacrifice, salvation, rebirth, the dark womb of the universe... it sounds awfully pretentious. ‘Pretentious’ is, however, a word one uses to describe failure. When the work in question succeeds in doing all these things, we usually go for ‘brilliant’ or ‘beautiful’. Revere is pretentious, but it nevertheless is not a failure.

A lot of it is thanks to Harrison’s artwork. It’s a shame the book is digital-only for now, because you really need to see the full page to experience what the creators are doing here. While it begins fairly normal, the story sheds the regular panel divide rather quickly. When Revere enters the other realm, the story takes flights of fancy to a new level. Every page becomes a new picture in a new style: a kaleidoscope of dazzling ideas, half-formed and quickly discarded. It would have been too simple to describe it as a drug hallucination, had Smith not explained to Goggans that he was going exactly through that while writing the latter half of the story: “It sounds pretentious but that whole last book was an act of catharsis, a way of clearing all that crap out of my head, and it’s probably the one story of mine I’ve no hankering to reread.”

This type of thing can be the most boring, most annoying experience in the world - listening to a friend coming down from a high, trying to describe half-remembered dreams that were probably dull even when full-formed. But Smith and Harrison are top-of-the-line storytellers, so they actually succeed in translating that feeling onto the page. And ‘feeling’ is the key word here. Smith’s comics are often not about their plots - they are about translating the emotional frequency he was on at the time into a visual language the reader can understand.

The problem with this approach is that it can often leave you hanging in the air, grasping at ideas the creator had completed in his mind but never fully transcribed to the page. For instance, there’s a romance at the heart of Revere: a love-interest figure that ends up falling for the protagonist’s innate goodness and self-sacrifice. He, in turn, is willing to tear the universe apart to save her. This love is never quite developed, it’s simply there - a love that exists more as a motivation for Revere to act, than something truly felt between two characters. This is a problem when your work is all about hidden connections between people and the universe. We should feel this love, it should burn us - but it remains cold throughout.

There’s a similar issue with the romance at the center of A Love Like Blood, a shorter Smith serial from 2001 (with art by a young Frazer Irving), which makes Romeo & Juliet into a vampire / werewolf couple. Fair enough - but the infatuation is never built into the story. It just happens, so we can move on to the next thing. I’ll give Smith points for giving it a shot; 2000 AD creators (to this day) rarely deal with matters of the heart. The old ‘boys comics’ atmosphere can lead to a lot of violence, coupled with view on sexuality that moves sharply between the prudish and the immature. Smith at least tries his hand at it.

That’s a key to Revere, and to a lot of Smith’s work overall, I believe. He constantly struggles against shackles – of the genre, the medium, the format, the business... he does things one ‘shouldn’t do’ and sometime manages to make them work. A true miracle when it succeeds, and a disaster when it flops. His (few) scenarios for characters he didn’t form from the ground up tend to be particularly less successful – his Judge Dredd stories are rambling affairs that have little to do but indulge Smith’s pet themes (which have nothing much to do with the strip). Concave peg in a square hole. His Vampirella run, well... it tried to be dumb action, and certainly achieved the first half of that equation.

Indigo Prime artist Chris Weston said of him once: “[Smith] needs some kind of straight man to reel in those flights of fantasy from which his strips often never return.” This was seemingly proven correct by Weston's highly-rated work on the Indigo Prime story "Killing Time" (the promo poster for which is one of my favorite pieces of 2000 AD art). What is Chris Weston is if not comics’ ultimate straight man? An artist of the Don Lawrence school (which is to say, he literally studied under Lawrence for a while), Weston can manifest every image the scripts demand of him as if it’s the most natural thing in the world. Smith tries to fly away, and Weston keeps him firmly grounded.

Nothing holds Revere on firm ground. If anything Harrison seems to be egging on his co-creator to go farther, higher. The script says: “Everything’s fluid here, flexible, reality like clay, like plasticine.” And the art indulges it fully. It’s beautiful and terrible at the same time. A maddening work to decipher; there is no key and no hope for an answer, but it's a powerful thing to experience. Which is probably a good summation, if any, of John Smith’s oeuvre.

There’s passion there, unencumbered by things such as ‘logic’ or ‘plot’. The work explodes from the mind of the creators directly at the reader. The only way to survive is to ride that mad shockwave; you can’t know where it will take you, only that it won’t be any place familiar.