Zippy, the character, not the comic strip, passed the forty-year milestone late last year, and on May 26, the comic strip celebrated its 25th anniversary, just the day before its creator, Bill Griffith, made a presentation at the annual convention of the National Cartoonists Society, a happy coincidence that escaped our attention altogether at the time. But to make up for our dereliction, we’re reprinting (and updating slightly) an interview we enjoyed with Griffith and published in Cartoonist PROfiles No. 101 (March 1994).

An elopement from underground comics, Bill Griffith's Zippy is easily the most unconventional comic strip in the King Features stable. And the circumstances surrounding its syndication by King are equally unusual. So eerie, in fact, that the entire episode could have been lifted intact from the strip itself.

In 1986, Griffith was doing a daily Zippy strip exclusively for Hearst's San Francisco Examiner and self-syndicating a weekly version to a small selection of newspapers. He had no ambitions for national daily syndication. Out of the blue, he got a phone call from Alan Priaulx, then Vice President of King Features, who wanted to meet him in San Francisco and talk to him. Griffith recounted the story when we talked in late September 1992:

"After a year of appearing daily in a large American newspaper," Griffith said, "I thought that was as weird as things were going to get for me. Little did I know they were going to get even stranger. Priaulx came out. I remember going to the meeting with a little list of things that I would require in order to work for them. And I had thought of the list as a way of not working for them: I was certain that they would never agree to these things. I said I have to keep my copyright. And I have to keep the larger format. I draw the strip out of proportion: it's taller than any other strip. It's not just that I want it to appear bigger proportionally: it's drawn so that it has more headroom [for dialogue]. And I said, I can't change that."

"You can't censor it," Griffith continued, recalling his list of requirements. "You can't edit it. You have to guarantee me a certain amount of money weekly because I'd be giving up my exclusive deal with the Examiner. I gave them a long list. I felt like I was taking hostages. And this guy sat across from me and said 'Yes' instantly to everything."

Six months later, Griffith found out why Priaulx had been so accommodating: "I got a letter from him at his new job, somewhere in some completely different business; he just wanted to tell me what had happened, how Zippy had come to King Features. He said he wanted to leave King. He wasn't happy; it wasn't the right job for him. But he wanted to leave with a bang. And he said he felt that by hiring me and by adding Zippy to the King Features roster he was leaving a ticking time bomb on their doorstep as he left. He just wanted to shake up King Features. He just wanted to give them the weirdest strip in America."

I asked the obvious question: "So—did the time bomb go off? Have you run into trouble?"

"No," Griffith said. "None whatsoever. And I'm very grateful for that fact. I've had nothing but support from them. At the very beginning—the first year or two when Bill Yates was the comics editor—I would get a call once a month or so, and he would say, Do you have to use the word Jesus in your strip; it might offend the Bible Belt people. The very first time he said something like that, I said, Bill—that's an essential part of the point I was trying to make in that strip, and I can't change it. And he instantly said, Fine—no problem. So, no trouble. It's been a completely happy relationship. I think what Alan Priaulx did they actually liked. They liked the shake-up that I represented."

These days—that is, 2011—according to zippythepinhead.com, Zippy appears in about 200 newspapers worldwide.

Zippy has a long history that begins several years before Griffith's association with King Features. The character—indeed, Griffith's career as a cartoonist—can be seen as the triumph of the Milton Berle over the Jackson Pollock within Griffith. The struggle began at an early age.

Griffith grew up in Levittown, New York, the post-World War II housing development that gave housing developments a bad name. All the houses looked exactly alike--a monotonous, sterile environment. But next door to the Griffiths lived "the only beatnik in town," the well-known science fiction illustrator Ed Emshwiller.

"Emsh" (as he signed his work) was an example to young Bill: he worked at home and made more money that Griffith's father. Although Griffith was fascinated by comics, he watched as Emshwiller began to experiment with abstract painting, and Griffith soon abandoned comics for painting. Except for Harvey Kurtzman's Mad. He appreciated its "subversive humor."

"Mad was a life raft in a place like Levittown, where all around you were the things that Mad was skewering and making fun of," he said. "Mad wasn't just a magazine to me. It was more like a way to escape. Like a sign, This Way Out. That had a tremendous effect on me."

But he still pursued the artist's muse, not the cartoonist's. After graduating high school in 1962, he went to Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and studied painting and graphic arts, leaving between his sophomore and junior years to spend a year in Paris, where he lived in a garret ("the top floor of a cheap hotel—I even had a skylight"). When he returned to Brooklyn in 1965, he freelanced at whatever art jobs he could find.

He moved to the Lower East Side of Manhattan in about 1967. There he saw his first underground comics, strips by Robert Crumb and Kim Deitch in the East Village Other. "I had repressed the comedian and the cartoonist in me for too long," Griffith recalled. "Seeing those Crumb things burst the bubble. I just did a comic strip one day [in late 1968] and took it down to Screw.

"The times being what they were, completely free-wheeling, it was relatively easy to get published. My message seemed to be sufficiently anti-establishment, anarchic— and, most important, I did the strip to the right proportions. I took it in to Steve Heller, who later became an art director at the New York Times, and he pulled out a ruler, and said, "Hey— it's the right proportions; we'll use it!" I was one of the few contributing cartoonists who had bothered to measure what a half-page tabloid size was. And I'd drawn it the right size. I don't think they even read my first five or ten strips. They were just so thrilled that they were drawn to the correct proportions."

I said: "So now all aspiring cartoonists reading this will seize upon the right proportions as the direct route to— "

" —to fame and fortune," Griffith finished with a laugh. "Just measure correctly. The ruler is the pathway to stardom."

Griffith completed his education as a cartoonist by seeing his drawings in print. "I remember seeing my first strip in print and having the elation fade in about two minutes--just staring at this thing and being embarrassed by how it looked. Thinking, 'My gawd—I gotta go back and improve that foot; this lettering is not readable.' And I started asking people what pens they used. I had to learn all the basics because I'd come to comics right out of painting. And doing art for black-and-white reproduction is a different game. I felt like I was drawing with a rock on concrete. Whatever grace I had develop with my art materials just evaporated when I was faced with a dip pen and a sheet of bristol, and knowing that the pencil wasn't going to help. It all had to be in ink; the pencil was just going to get erased. Everything was very tentative at first, but I am grateful that I had the opportunity to learn—in print—because that's the best place to learn. Seeing your work in print is almost like seeing it through someone else's eyes. You get this objectivity that you can never get from your original art."

Throughout 1969, Griffith's strips appeared in Screw and the East Village Other. Among his characters was an anthropomorphic amphibian, Mr. Toad. Mr. Toad was anger incarnate, primal anger; and he acted out his anger. Through Mr. Toad, Griffith assaulted the shams of the society around him. "He was cathartic," Griffith said.

In early 1970, some of Griffith's cartoons were published in Yellow Dog Comics in San Francisco, by then a mecca for underground cartoonists. Griffith made a visit to San Francisco in April 1970, when his first underground comic book, Tales of Toad No. 1, appeared; then he moved there in July.

"It was a magnet," Griffith said. "There was no resisting the pull of San Francisco." For an underground cartoonist, it was, by then, about the only place to be. The underground newspaper comic strip in New York had expired by the end of 1970; comic books were the only outlet, and they were published most regularly in San Francisco. "Within a very short time, almost all the cartoonists had either come out here [to San Francisco] or had stopped doing comics. Everybody came out. I was just part of a wave of people coming out here."

For most cartoonists, cartooning is essentially a solitary occupation, but the ambiance of San Francisco at that time was more like the fabled Mermaid Tavern of Elizabethan times where people got together and chewed the fat and talked about what they were doing.

"It was like an art movement," Griffith said. "You joined an art movement; that was the feeling. It was a lot of things. First of all, it was a definite part of the hippie movement, the counter culture. We were part of the whole Haight Ashbury scene. By 1970, it had started to fade—or change, at least, the tail end of the counter culture—but it was still very much alive in the social sense of everybody feeling connected. There was a kind of party atmosphere to some degree; and then there was the sort of salon atmosphere. We hung around a comic book store called San Francisco Comic Book Company on 23rd Street in the Mission District here—which still exists and is run by the same owner, Gary Arlington, who eventually became a publisher and then that faded, and he's still at the stand selling comic books [it was in 1992, the vintage of this interview, but it's no longer open]. If we were a salon, he was Gertrude Stein. In fact, he kind of looked like Gertrude; he looks more like Gertrude Stein every year. We would hang out at the comic book store, and we would have regular parties at the publishers' offices, Rip Off Press and Last Gasp."

[For more about the Haight in those years, visit Harv’s Hindsight for July 2007, “The Lonely Hearts Club Band,” wherein is retailed a short history of underground comix and Robert Crumb’s career.]

The comix salon atmosphere often crackled with the causes of the counter culture's crusading spirit. Griffith explained:

"There were plenty of factions within underground comics just as there were within the prevailing counter culture so that some cartoonists felt a responsibility to promote certain ideas. And that's how Last Gasp was formed. Last Gasp was—and still is—officially called Last Gasp Eco Funnies, meaning ecology. [So] Last Gasp was not interested in printing Young Lust No.1, which was my first big hit, because they had a fairly strict, politically correct attitude, and Young Lust didn't fit into it. They thought it didn't have any socially redeeming qualities; and they were into printing things that were politically correct in terms of late-sixties early-seventies politics of the counter culture. I was always a little bit on the outside of that."

Griffith's Young Lust No. 1, a satirical parody of "young romance" comic books, appeared in October 1970 and was successful enough that from then on, Griffith was able to earn his living solely as a cartoonist. By working for every underground comic that would take him, he managed to support himself. "At the ridiculous page rate of $25 a page," he said, "if you worked really, really hard, you could make $100 a week."

He had one "bad year"—1973-74, the year the Supreme Court ruling on pornography virtually shut down production of underground comix. During that time, he worked with Art Spiegelman doing Wacky Packages for Topps Bubblegum. In 1975, he joined Spiegelman in founding Arcade Comics, which the two edited (with the help of Willie Murphy, Griffith's roommate at the time) for seven issues. When it folded in 1976, Griffith started doing a weekly half-page comic strip for the Berkeley Barb. The strip was soon being distributed nationally to the underground press by a syndicate that Rip Off Press started. The strip was Zippy.

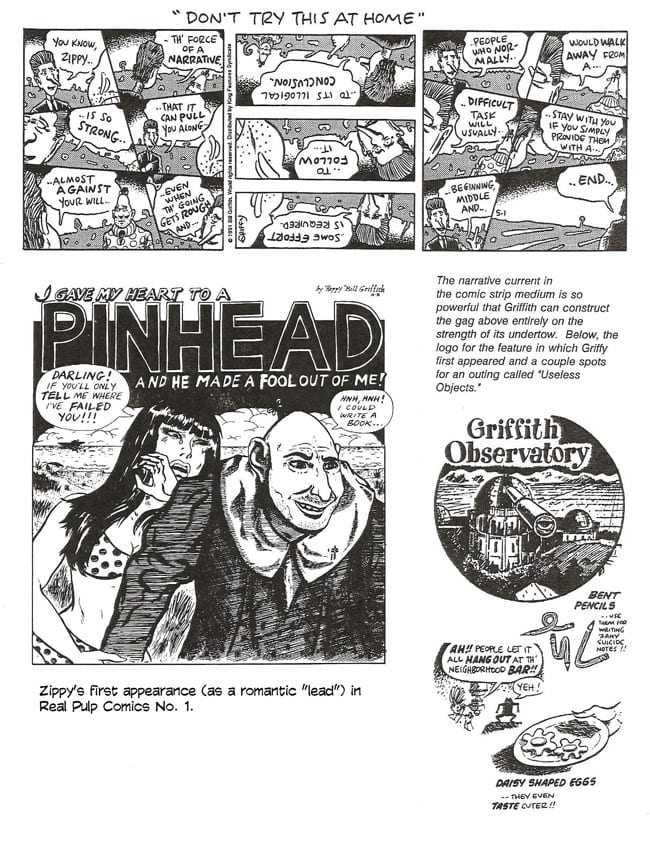

Zippy the Pinhead first appeared as a comic character in a "true romance" satire that Griffith did in Real Pulp Comics No. 1 in late 1970. "Roger Brand—a cartoonist now deceased—was editor, and he urged me to do a really oddball romance story that took some unexpected turns and used characters that normally don't appear in romance comics—not Mr. Toad but something equally odd. I had recently seen the movie Freaks, and I thought, Hey, why don't I use one of those pinheads from Freaks; that would be a pretty interesting character. Just for a one-shot story. And I went to visit a friend who had freak photographs, collected photographs of circus sideshow freaks.

"So I had all these pictures," Griffith continued, "and I did a story, a sort of ‘true confessions,' called ‘I Feel for a Pinhead but He Made a Fool Out of Me.' And Zippy didn't even have a name at the beginning. In fact, he got his name during the strip. And it was a very baroque love triangle involving two pinheads and a so-called normal female. So Zippy was born in that story without ever—on my conscious part anyway—having any intention to draw him again."

Zippy's name, Griffith once revealed, was derived from "Zip the What-Is-It," a pinhead exhibited for years with the Barnum and Bailey Circus. "His real name, by the way," Griffith added, "was William H. Jackson, the same as my great grandfather. And, since my full name is William H. Jackson Griffith, it's all the more unnerving." Later, when Griffith needed a sidekick for Mr. Toad, he brought Zippy back into the picture, and within a year or so, the roles were reversed, and Mr. Toad became Zippy's sidekick.

Zippy's name, Griffith once revealed, was derived from "Zip the What-Is-It," a pinhead exhibited for years with the Barnum and Bailey Circus. "His real name, by the way," Griffith added, "was William H. Jackson, the same as my great grandfather. And, since my full name is William H. Jackson Griffith, it's all the more unnerving." Later, when Griffith needed a sidekick for Mr. Toad, he brought Zippy back into the picture, and within a year or so, the roles were reversed, and Mr. Toad became Zippy's sidekick.

I speculated: "So what you were looking for was a character with a personality the opposite of Mr. Toad?"

"Yes," he said, "Toad was an overbearing, hostile, egomaniacal self-destructive character who lived in the bubble of his ego. He couldn't really understand anybody else's existence much less their problems. Zippy was the character who didn't even recognize the border between himself and the world. It was one seamless reality to Zippy. Zippy also embodied some Zen qualities that I can relate to."

Rip Off's syndicate operation ceased in 1980, and Griffith started self-syndicating the feature through his own Zipsynd (later Pinhead Productions). Zippy also appeared in the National Lampoon and High Times from 1977 through 1984. In 1985, Griffith got a phone call from William Hearst III, who had just taken over the San Francisco Examiner. "He wanted to shake up his readers," Griffith said, "and he proposed that they run Zippy. I thought he wanted to buy my weekly strip, but, No—they wanted a daily. I just sat there kind of stunned. I said, You mean you want to run it like a daily strip? Next to Blondie?"

Zippy began running five days a week, then went to six. "[Hearst] wanted to attract readers," Griffith said. "He wanted to make the paper look different, get a younger audience. And Zippy did increase circulation. He told me that it increased circulation by about 10,000 during lunch: suddenly they had a huge lunch hour readership that they'd never had before. Younger people were buying it and reading it at lunch. The same thing happened with the Boston Globe when Zippy first started."

"What a testament to the power of a comic strip!" I said.

"Yeah, it still has that power," Griffith said. "And newspaper editors who buy Zippy don't expect it to appeal to everybody. They are trying to get that younger readership—the hipoise, the thirtysomethings and fortysomethings and in many cases even younger readers, readers who don't expect to see Zippy there, then hear about it and then buy the paper just because it's there." After about a year, Alan Priaulx called Griffith, and within weeks, Zippy was in national syndication, beginning May 26, 1986.

Griffith continued to distribute Zippy weekly to the client papers he assembled while self-syndicating the strip. "I asked to keep the right to do that," he said. He sends a selection of the daily strips from which the weekly papers pick one to publish. At the height of the program, he was sending to over 50 papers; then it dwindled until it reached about 10 by 2000. “I still have one weekly that I send strips to,” Griffith told me recently, “—the San Diego Reader.” King Features takes care of whatever remains of the original list.

Pinheads, Griffith told me, actually exist. Scientifically speaking, they're called microcephalics (meaning "small head"). Missing their frontal lobes, they don't have the power of reasoning, but many of them can function and hold jobs. "They're not quite retarded; they're short-circuited," Griffith said, recalling his visit with one of them. "The way they tend to talk resembles very much clicking your remote control device on the TV every 10 seconds. Which is, by this point in American history, a very common, understandable way of thinking because most people sit in front of their tv’s clicking their remote controls every day. They might be getting frighteningly close to the way Zippy thinks," he joked.

By the sheerest luck, Griffith met a genuine pinhead named Dooley. As recounted at his website, zippythepinhead.com, “the cartoonist took notes as Dooley explained why Walter Cronkite was God, uttering a dizzy stream of nonsequiturs such as ‘Are you still an alcoholic?’ Similarly, Zippy responds to most situations with seemingly out-of-context phrases, including: “I just accepted provolone into my life’; ‘I just became one with my browser software’; ‘Frivolity is a stern taskmaster’; and ‘All life is a blur of Republicans and meat.’”

Griffith readily acknowledges that his strip is an acquired taste: "I'm not trying to do a comic for the masses. I'm not trying to appeal to every demographic slice. I'm not consciously trying to appeal to anybody but myself. Although I'm not trying to alienate people. This is not a domestic strip, a strip in which you can instantly recognize archetypes—like, for instance, For Better or For Worse. A strip in which you can say, Oh yeah—I've thought that, I have a relationship like that, I have a family, I have a cat, I have a dog. None of those things apply. You have to sort of tune into my wavelength and that might take a little while. My previous audience [for underground comics] was already convinced they liked it. But coming into daily newspapers, I was suddenly confronted with a whole range of readers who would read Garfield and who, two second later, would be reading Zippy—which never, in my wildest imagination, did I think would ever happen. So I have a whole new audience to either convince to get on my wave-length or to outrage and anger. And I get plenty of both."

Reader response to Zippy runs the gamut. In reader polls, Zippy often comes in last—"but last in a spectacular way," Griffith said. "Deep, deep hatred from the readers. Not just, Get rid of that strip; I don't like it. But—I don't like it because—. And they list a whole slew of reasons why they don't like it. They don't get it, and they really, really get angry. They obviously keep reading it, too; they don't just give up after ten days. They keep reading it and getting more and more angry. And what happens to these people is that they reach some kind of critical mass point and they suddenly understand it. Some of them. Not all of them. In the meantime, if the reader poll happens and they're in this stage of irritability because they don't understand it, they're angry. One woman just wrote saying, What is he? A homicidal maniac? That's all she could say. One of them said, What is it? A guy in a dress?"

"But I get a lot of satisfying response from readers who get everything I do, and I'm always kind of amazed when that happens. The Washington Post dropped Zippy about three years ago and received so much mail from die-hard Zippy cultists that they put it back in. I'm happy if an editor actually drops the strip and then puts it back in under pressure from readers; that usually means it's in forever."

Starting May 6, 1990, Zippy appears on Sunday in the sixth-page format. Griffith enjoys working with color and does lots of special effects. Like the time shortly after the Sunday version started:

"I did a strip about the color printing process," Griffith said. "The two main characters, Zippy and Griffy, each held up little blocks of zipatone dots of different colors and then put them over each other to create other colors. And Griffy's explaining the whole four-color printing process to Zippy— just having fun with, say, purple. Then Griffy says, And this is an example of off-register color. And so that entire panel I specifically colored to be off-register, very much--obviously off-register. When the printers of the Baltimore Evening Sun saw this once it got on the press, they thought that it was off register. They didn't sit and read the strip; they just looked at it and thought it was off-register. And they attempted to correct the registration—and thereby threw off the registration of every single other comic strip on the page."

"And I have that page; someone sent it to me," Griffith concluded. "It's a wonderful little moment."

(Continued)