If French press cartoons are unashamedly rude, what's at the heart of such a caustic culture? To find out, you just need to meet its great practitioners. Some of their names, albeit dusty, are still revered: Honoré Daumier, Nadar (Felix Tournarchon), and André Gill. But many more – once celebrities with powerful pens – are now obscure. Outside of experts, who mentions crazy guys such as Henry Monnier and Jean-Pierre Dantan?

I found the answers in a current Paris exhibition, Caricatures: Victor Hugo On Page One. It's a show focused on the man who wrote Les Misérables, but one that tells his story wholly through caricature. In the exhibition are almost two hundred drawings, many rarely if ever shown, that take you straight to the art's historic heyday.

To revive that era, Hugo is a perfect choice. His eighty-three-year life (1802–1885) coincided with both technological change and huge events. A supersized ambition kept him at their centre and, being a Royalist who defected to socialism, every sort of detractor got to take a shot at him.

No human life supplies the satirist's every need, but that of Victor Hugo certainly came close. Hugo was a prolific, epic intellect and also an epic over-achiever, braggart, philanderer, self-promoter, schemer, liar, and nostalgist. His modern legacy may be the Les Misérables musical but the author's stardom was already global during his lifetime.

Before Les Misérables, no novel had ever triggered such a world-wide, multimedia phenomenon. Announced by the New York Times two years in advance, Hugo's book was published simultaneously in Paris, London, Brussels, Leipzig, and Saint Petersburg. It sold like hot cakes not just in Europe but also in China, Russia, and South America. Even today, in Vietnam, a religion called Cai Dai worships the author as a saint.

Hugo made his first made waves as a Romantic poet and playwright. Thanks to The Hunchback of Notre Dame, he was a star before he turned thirty. The Hunchback even saved Notre Dame Cathedral which, at the time of its writing, was viewed as just a shabby relic. Les Misérables, however, canonized its author – despite the fact that, opposed to the Emperor, Hugo was then living in exile. The nineteen years Hugo spent outside France (he promised to reappear "only when liberty does") clinched his standing as the conscience of a nation.

At Hugo's Paris funeral, the crowds were bigger than the city's actual population. But see their idol through the eyes of a caricaturist, someone like Honoré Daumier or Benjamin Roubaud, and you're not looking at any kind of idol. The Hugo they drew, a man many knew, is a conceited, exhausting, self-regarding blowhard. Cranky and belligerent, only one thing drives him: his tireless attention to the needs of Victor Hugo.

This was the Hugo who kept a pocket notebook so he was ready to record his own eloquence. The Hugo whose diaries exude self-satisfaction ("Photographs of myself are being hawked in the street!"). A man who lambasted the Emperor yet mused about becoming a French dictator: "Dictatorship… I shall have to bear that burden."

This Hugo gave the caricaturists great material but, from the start, he was a canny target. Although consistently mocked by the press, the writer was always attentive to his media standing. He once consoled a colleague who feared ridicule with the words, "But remember… every item is good! When you're building your monument, everything is good! Some bring marble and others rubbish. But all of it is useful!"

When Hugo wrote those words, the French throne was occupied by Louis-Philippe. Louis was a "constitutional monarch", installed in 1830 by a second revolution. For artists and writers this was a pivotal event, because it gave them a (brief) taste of freedom.

Liberty of the press was declared in 1789 but it took 92 years to achieve. The French press freedom law passed in 1881, a law still in effect today, ended almost a century of unforgiving controls: 42 separate laws with 325 clauses. French satiric art was born under and shaped by these. After 1835, the state prohibitions ranged from bans on criticizing the king and later the emperor to injunctions that outlawed any and all political cartoons. Additional curbs came in the form of fines, stamp duties and postage hikes on papers sold by subscription.

While the government switched between royals and revolutions, liabilities were a constant for French editors. Publishers and printers, too, remained vulnerable. Usually an artist had to have advance permission, in written form, from anyone he wanted to draw. Their ingenious begging letters are one of the show's great curiosities.

From Jean-Pierre Dantan, born in 1800, to Albert Robida, who died in 1926, all sixty artists on show struggled under these rules.

Their one taste of freedom occurred between 1830 and 1835. This window also saw the spread of new technologies, especially lithography and wood engraving. Such breakthroughs meant that three publications – La Silhouette, La Caricature, and Le Charivari – were able to engineer French caricature's Year Zero.

All three papers involved an editor and publisher named Charles Philipon. Philipon is famous for his battle with Louis-Philippe, who soon revealed himself as an enemy of the press. Over almost two decades, with caricature as his weapon, Philipon battled the "bourgeois king" unceasingly. He suffered constant lawsuits and spent more than a year in jail. When critical imagery of the ruler was forbidden, Philipon depicted his nemesis by sketching a pear. His ploy was taken up at every level of society with pear drawings, poems, allusions and graffiti. It was a perfect gambit – even the illiterate could grasp the link between his fruit and the head of their king. The pear's artist perpetrators were fined, harassed, and jailed but their subversive trick remains legendary.

Philipon's fame doesn't come from his pear alone. All French caricature has English roots; the satires of Hogarth and Gillray were famous all across Europe. English journals also ran cartoons and illustrations. But it was really Philipon who made satirical image and text into halves of a whole. He understood laughter and its potential with a visceral force. "Talking seriously bores me," he once wrote to a friend. "I prefer attaching a little bell to my idea… The more serious or the wiser I believe it to be, the more I like seeing it run about disguised as lunacy."

Philipon was a brilliant editor, greatly loved by his colleagues. But, to a man, they were astonished by his imagination. Next to countless works of the era you often see the phrase "Charles Philipon inv." The initials stand for 'invenit'; i.e. Philipon supplied the drawing's concept.

The editor also brought caricature a business model. Philipon's radical papers were sold by subscription; they had a limited reach and never made money. But the company he co-owned, Maison Aubert, was a different story. Aubert had three identities: it was a combination print works, publishing house and retail boutique. This popular shop, which flourished through 1851, sold print versions of the satirical papers' drawings. It also expanded their cartoons into albums. Here, the collector could make up portfolios, assemble ongoing series of prints, or buy ready-made albums.

The French "petit presse" exploded after 1830, with many of its new publications dealing in satire. The French public's growing taste for comic visuals had been primed by a set of oddball characters – cartoon figures used for jokes that were often political. These included the uppity fabric clerk "Monsieur Calicot" and the hapless hunchback "Monsieur Mayeux." Mayeux, also called "Mayeaux" or "Mahieux," was drawn by several artists and appears in two tales by Balzac. But his real fame came via the artist Traviès (Charles-Joseph Traviès de Villers). In terms of political incorrectness, Traviès' Mayeux portraits raised the bar.

Like Honoré Daumier's character "Robert Macaire," all of these were figures which already existed. Each was just being rendered timely for a changing audience. But a different kind of protagonist also appeared: a plump, dim bourgeois by the name of "Joseph Prudhomme." Prudhomme was created in 1830 by Henry Monnier. An actor as well as an artist, Monnier brought his character to life onstage.

This two-way street was a common one; in 19th century Paris, image, performance and text mixed quite happily. As a successful poet, playwright and poser, the young Victor Hugo epitomized this culture. It was one whose popular papers gossiped about and satirized theatre but also wooed readers via serial dramas ("feuilletons"). In addition to these and illustrated stories ("histoires en images"), papers published the novels of Hugo, Balzac, and Alexandre Dumas by installment. Caricaturists mocked all of it and the cartoon versions of Hugo's novels by "Cham" (Amedée de Noé) and André Gill were famous.

This print revolution engrossed the whole 19th century. But for those in the French capital, its dominant subject was always life in Paris. From fashion to new buildings, manners to merchandise, everything that happened was noted, scrutinized – and mocked. This enthusiasm produced some quirky spinoffs such as the illustrated pamphlets called 'Physiologies.' Thought up by Philipon, these posed as "guides" to the city's different tribes. The social groups they cartooned included Hugo-esque dandies but included esoteric groups such as ragpickers, bluestockings, debtors and carnies.

To the audience, it was all riveting. Parisians, as Baudelaire noted, loved nothing more than gazing into any mirror that reflected them. Critic Walter Benjamin would christen the era's literature "panoramic," because of its obsession with summarizing the city. Everything that went into modern life attracted artists.

Even Paris shop windows served as public attractions. As in 18th-century London, those of Maison Aubert served as a free cartoon museum. While the publications on view sold by subscription, anyone was free to come and gawk at the prints. Combined with the city's cabinets de lecture (public reading rooms) and the fact that all cafés stocked and "rented" papers, local cartoonists' work enjoyed a broad diffusion.

Caricature's expansion fed on Victor Hugo's fame, something apparent from the show's wild ephemera. Cartoons of the novelist could be found on china plates, on ladies' fans and matchboxes. They also helped sell comic pamphlets, calendars and diaries. The ever-expanding world of print became a merchant's playground – one for which Philipon produced cartoon wallpapers. Drawn by Cham and Gustave Doré, these became a subject of satire in their own turn.

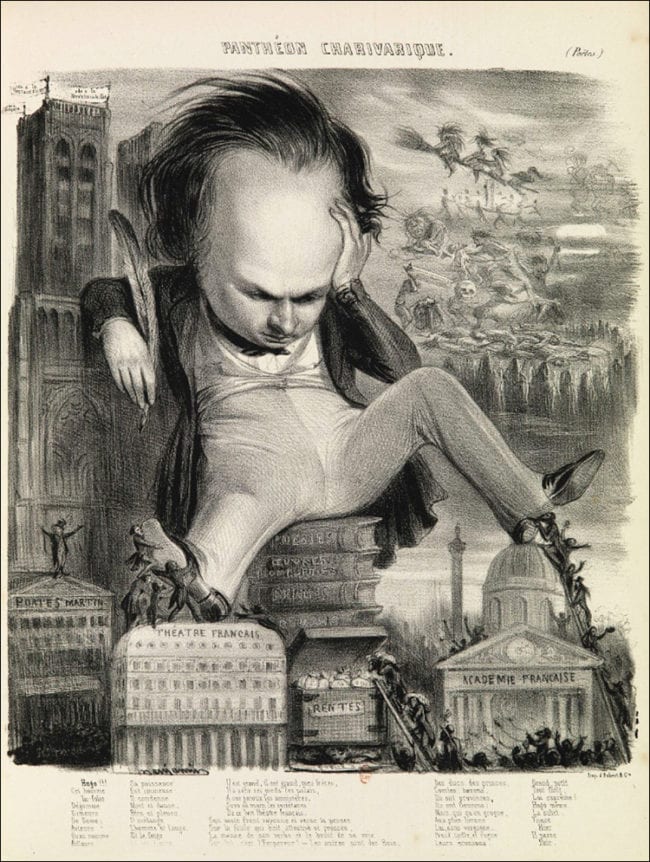

The challenges of censorship led to countless ruses, all of which built immense graphic resourcefulness. Jokes about Hugo, for instance, were made using buildings: the theatres where his plays appeared, "his" Notre Dame Cathedral or the Académie Française he was longing to enter. (Hugo made five attempts at election to the Académie, a feat became the subject of massive scorn.) Drawings by Grandville, Daumier, and Roubaud depict the writer begging at institutional doors or show him aggressively squatting Parisian cultural landmarks. He also tucks the Notre Dame cathedral under an arm or wears its signature towers as a hat.

In all these drawings, one message is clear: to Hugo, everything is just a tool for personal glory.

Caricature even knew how to represent censorship. After appearing for years in different guises – usually as some sort of devil armed with giant scissors – the censor was codified as a character. André Gill transformed "her" into "Madame Anastasie." This name came from the Greek for "resurrection" and traded on the fact that, despite many defeats, French press restrictions could be counted on to return.

Like the marriage of elegant lines with inelegant tropes (the enema syringe was popular), such cartoons wove together savagery and sophistication. But, as the expo demonstrates, not all satiric publications were left-of-center. Although a large number were indeed republican, others espoused monarchist or Catholic views. These conservative papers attracted conservative artists but they produced graphic stars of their own. One of them was the baron Charles-Marie de Sarcus (1821-1867) who, because he needed crutches, went by "Quillenbois" or "Pegleg."

Quillenbois was the lead artist at Le Caricaturiste – a journal named in opposition to Philipon's La Caricature. Like Albert d'Arnoux ("Bertall"), whose background was similar, de Sarcus initially approved of Hugo the Royalist. But, when Hugo moved to the left, the pair of nobles went for him. Their critical drawings have titles like "A Brain Full of Mush" and captions such as "Victor Hugo is entirely lacking in political morals, political science and political ideas."

Whatever their politics, caricaturists all suffered under the French censor. Between 1878 and 1881, for example, the right-wing Le Triboulet weathered thirty-seven different prosecutions. One of its editors received six months in jail and its Irish-American founder, James Harden-Hickey, found himself expelled from the country. (Ironically, Le Triboulet was named for a character in one of Hugo's plays, Le Roi s'amuse, which was itself suppressed.)

In the efforts to evade such condemnations, caricaturists made greater and greater demands on their audience. As the French cultural critic Daniel Salles puts it, "Caricature pre-supposed a set of skills; it required cultural, rhetorical and linguistic abilities. Both physically and politically, its reader had to know everyone in power. He had to be up-to-date on all the news and politics. But he also needed a certain erudition, so he could comprehend numerous cultural and historic allusions."

After the passage of one-and-a-half centuries, it's not easy to resuscitate such skills. But the graphic brilliance of the cartoonists endures and Caricatures can boast some revealing rarities. One is a tiny bust by Jean-Pierre Dantan (1800-1869) – an item only inches high. For half a century, this diminutive image fueled the cartooning of Victor Hugo. Its enormous forehead, framed by receding hair, became a trait as omnipresent as the author himself. Systematized in drawings by Benjamin Roubaud and Honoré Daumier, the visual logo dogged Hugo all his life.

Dantan himself was a portrait sculptor. At the of age of 26, merely for a laugh, he made a few busts that caricatured his artist friends. When one was put up for sale, however, it caused a sensation. Before long, its creator had a second career. (At one point, he even opened a caricature museum which was called "The Dantanorama".) All Dantan's 3-D portraits have real dynamism and their animation inspired his close friend Daumier. Daumier began making caricature heads of his own, eventually creating a wonderful set for Philipon. They remain on permanent display in the Musée d'Orsay.

But it was another artist who spread Dantan's vision of Hugo. When he started work for Philipon in 1830, Joseph Germain Mathieu Roubaud was only 19. Trained as a serious painter, he became the magazine's benjamin – its "youngest sibling." Taking the nickname as a nom de plume, "Benjamin" went on to make two conventions fashionable. One was the big head-and-tiny body prototype. The other, which faded with the 19th century, was a satiric vehicle known as the "pantheon."

Benjamin's pantheon idea came from a current event: the unveiling of a new pediment on the Panthéon building. Begun as a church back in the 1700s, this was an edifice that embodied political change. In 1791, the Revolution made it a secular tomb for the country's "greatest men." But, between 1806 and 1830, it was recovered by the Catholic Church. The second French Revolution, in July of 1830, saw the structure once again deconsecrated. Two decades later, after 1851, it was re-activated as a centre of worship.

Only in 1885, with Victor Hugo's burial, was its status as a non-spiritual shrine made permanent.

The building's final pediment appeared in 1837, at the height of that Romantic movement led by Hugo. The sculptor David d'Angers had spent five years on it. D'Angers' masterpiece was a classical allegory – a march of heroes that starred Voltaire, Rousseau and Napoleon. But, less than a year later, Philipon's Le Charivari announced "an update." The journal's contribution was a "Panthéon Charivarique", a "Charivarique Pantheon" presented "hero by hero." This parade – published one caricature a week – came from Benjamin and privileged modern actors, authors, artists and cartoonists.

The Charivari's readers were free to choose their own great men.

Caricature already had parody processions. Cartoonists produced cavalry charges, comic pageants, funeral cortèges, parades (the sideshows seen at fairs) and similar sorts of cavalcade. Actors were also drawn in "galleries" of their roles. But, if Benjamin's idea owed something to all of them, it was more conceptual. A procession that "took place" over time and put its reader in charge of the composition, was of course a sales strategy. But it was not least an assertion – a declaration that the modern mattered as much as the classical.

Just one thing united Roubaud's "heroes" and it was their shared desire to be seen as great. To indicate this graphically, he drew them all with outsize heads and minuscule bodies.

It was a gambit Benjamin had pinched from Dantan, but it was also a gibe at David d'Angers. The real Panthéon's artist was famous for medallions and busts – all of which featured the heads of tony society figures. (It didn't help his cause that d'Angers hated caricature.)

Philipon's artists used the slang terms "masque" (mask) and "boule" (ball) for face and head. Their pear adventure had sparked a certain detachment, an impulse to graphically separate heads from bodies. Daumier, for instance, drew a set of disengaged crania – with a pear included – that he called 'Les Masques de 1831.' He, Grandville, and Traviès, all admirers of Dantan, kept on playing with their graphic guillotine. But it was Benjamin who made the big head a brand. Roubaud turned it into "the caricaturist's calling card."

It was also Roubaud's Panthéon Charivarique that crystallized Dantan's image of Victor Hugo. Benjamin's version nailed the author's Achilles' heel – the fact that, despite all his talent and his Romantic stance, Hugo was and would remain thoroughly bourgeois. Roubaud pictures him lost in meditation, propped atop cultural landmarks by Lilliputian acolytes. Although absorbed in his wild Gothic reveries, Hugo has one elbow firmly anchored on Notre Dame. Between his legs he also guards an overflowing box, one that bears the label "Rentes" or "Private Income."

Roubaud's big heads made his name. As an artist, he delighted in seizing a victim's definitive traits and he loved to play with noses, silhouettes and hair. He also understood how to capture his subject's movements and combine them with his physical characteristics.

The combination of novelty, innovation and pointed politics made the Panthéon Charivarique a sales phenomenon. It ran for four full years. In 1838, the year of its debut, single prints of its caricatures cost 75 centimes. But if a customer ordered twelve in advance, the price of each one was reduced by a third. Before long, "Charivarique" had appeared in the dictionary and, during its final months, new Panthéon prints only cost 50 centimes. The final year's collection was a special holiday supplement with Victor Hugo's portrait for a cover. Pride of place inside, however, went to Roubaud's self-portrait: the artist as a vandal, scrawling his version of Hugo on the Panthéon wall.

Especially in work by Daumier and André Gill, such big heads continued to proliferate. But if the 19th century was known for "panoramic literature", Benjamin Roubaud gave it panoramic caricature. Sensitive to the profits that could be made from serial works, artists produced a flood of "galleries", "museums" and processions. The pantheon mutated into different forms but it remained healthy through the century's end.

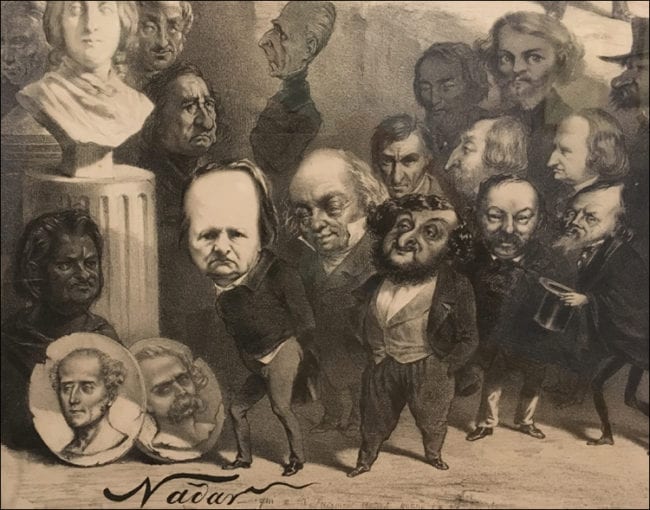

The most famous pantheon of all came from Nadar (Felix Tournarchon). Remembered today as a pioneer of photography, Nadar first made his name through caricature.

Nadar's cartoons took off when he met Philipon, who started publishing him in 1848. This was the year of a third French revolution, the insurrection which gave rise to a long-dreamed-of Second Republic. But this Republic was headed by a royal – its President was the Prince Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte. Since Louis was the nephew of Napoleon I, French Republican freedom looked shaky from the start.

In a weekly journal called La Revue Comique à l'usage des gens sérieux (The Funny Paper for Serious People), the left-wing Nadar pilloried Bonaparte unceasingly. One of his weapons was "Môssieu Réac" ("Mr. Reactionary"), a character he invented for a text comic. Réac was an opportunist and shameless political changeling, through whom Nadar mocked both the president and his cronies.

The monomania of La Revue Comique made some odd bedfellows. Its staff included not just Nadar, a diehard republican, but also his opposites: Quillenbois and Bertall, the right-wing aristocrats.

On December 2, 1851, Louis-Napoleon mounted a decisive coup d'état. Despite Parisian opposition – in which Victor Hugo took part – he became an emperor, Napoleon III. For every French republican, his Second Empire represented the end of hope. It was a worse-than-Trump scenario, a complete and total defeat. Also, due to that censorship installed from its start, no further opposition to the regime was possible. The heartbroken Nadar, still only 28, needed some creative cause to keep him going. He found it in the idea of a "Panthéon Nadar."

Louis-Napoleon's coup had also changed Hugo's life. With his existence in danger, the author became an exile. Any and all mentions of his name were prohibited. Two weeks later, however, Nadar published a mini-pantheon he called "A Magic Lantern of Authors and Journalists". Its procession of writers was led by a defiantly-drawn, big-headed Hugo.

Nadar got away with it and the adventure provoked a bigger idea: he decided to create the ultimate in pantheons. The artist envisioned it as a definitive work, a testament to the modern arts that would feature a thousand artists. Instead of serial portraits, this would be one huge composite. He decided to present it in four installments, each a giant print of 250 drawings.

Nadar was by now in charge of his own studio, a busy operation that had a dozen employees. A tall, charismatic redhead, he was a serial enthusiast – and a chronic overachiever. Already his binge passions had included self-publishing, epic parties, novel-writing and the battle for Polish freedom. Yet to come were hot-air balloons and photography.

For two years, however, Nadar remained immersed in his pantheon. Hounding his assistants for help, he amassed cartoons and cuttings, cajoled the famous into sittings and worked up caricatures. But, where Benjamin's Pantheon Charivarique had minted money, Nadar's extreme version did the exact opposite. It was too complex, too ambitious, too unwieldy. Only one of its giant processions – the writers – was ever completed. (It was, of course, led by Victor Hugo.) Today, a copy of Panthéon Nadar can sell for €3,000. But in the artist's lifetime, when it cost twelve francs, less than two hundred were ever purchased.

If Nadar's dream was a bust, its results were fortuitous. To recover financially, the Panthéon Nadar's creator was forced to focus on a sideline: his photography. He went on to produce some of history's most soulful – and most beautiful – portraits. Not only did Nadar show us what Daumier, Gustave Doré ,and Baudelaire looked like. In his wonderful photographs, we still feel their presence.

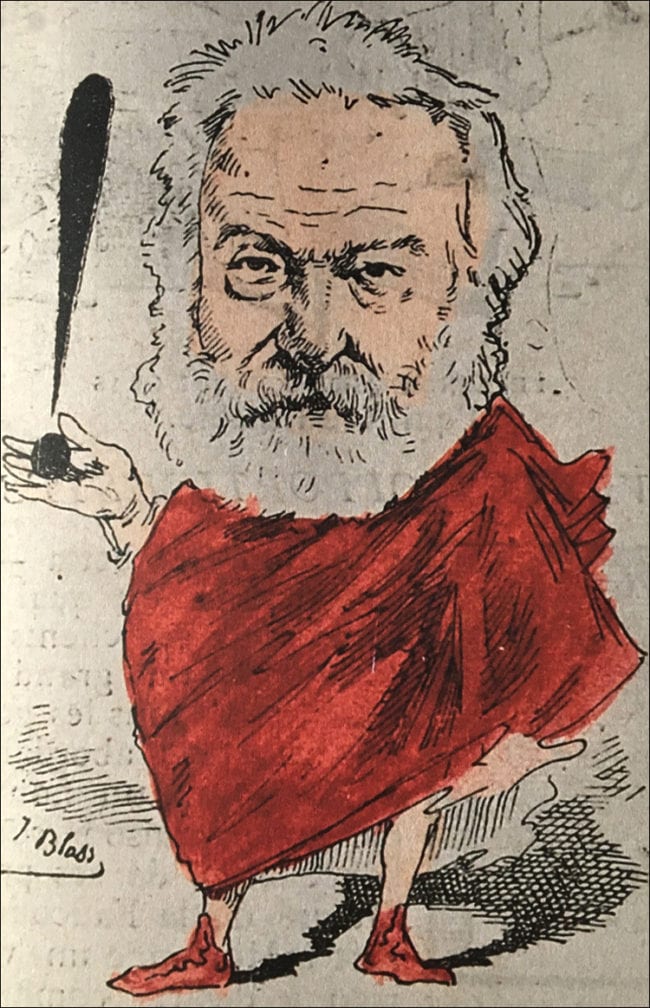

Charles Philipon passed away in 1862. But not before he managed to launch a final caricaturist. Introduced to the editor by Nadar, this was the nineteen-year-old André Gill (Louis-Alexandre Gosset de Guînes). In Le Journal amusant – one of two successors to his Le journal pour rire – Philipon promptly published one of Gill's Hugo parodies. He then hired the artist to take up an annual feature, the caricature version of each year's Salon d'Art.

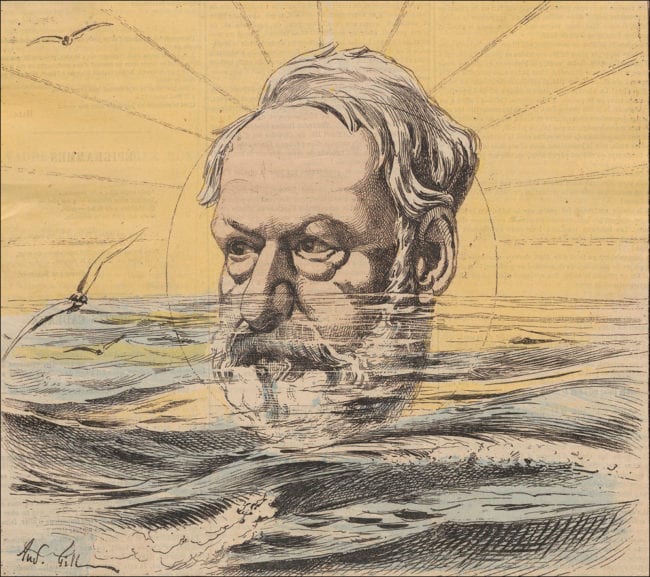

When Philipon died, publisher François Polo stepped in to champion Gill. Polo had just launched a left-wing paper of his own, La Lune (The Moon). Within a year, Gill's big-headed portraits had made its name. In partnership with the Spanish-born satirist Manuel Luque, Gill also drew pantheons of his own, the portrait series Les Hommes du jour and Les Hommes d'Aujourd'hui ("Men of Today"). But, towards the end of 1867, because of a Gill cover that was recognizably the Emperor, censors shuttered La Lune. Its staff re-grouped the following year – under the new title L'Eclipse.

Graphically, Gill's work at L'Eclipse influenced a generation. For more than a decade, he was a Paris cartooning star and the foremost re-interpreter of Roubaud's style. But Gill's heads were even bigger and they came highlighted in garish colors. The artist, who was also a singer, led a frenetic life, which he spent mostly in the bars and cafés of Montmartre. In Gill's heyday, writes French media scholar Bertrand Tillier, "His caricature was less an offshoot of Parisian life than a central actor in it. He kept the news in competition with his treatment of it."

Gill was a serious fan of the exiled Victor Hugo. After sixteen years of absence and the worldwide fame of Les Misérables, French censors started to look more kindly on the author. In 1867, they allowed one of his early plays to be revived. Gill marked the moment with a cover for La Lune in which Hugo's giant head was disembodied. The artist depicted the writer as a radiant sun, illuminating all around him. Gill captioned the portrait with one of Hugo's quotes: "I want all of liberty just as I want all the light."

This homage changed the tone of Hugo's depiction. At a swoop, the swollen head of Dantan and Roubaud went from a symbol of egotism to one of wisdom. Mockeries of Hugo's infamous temperament faded and, as artists were once again allowed to draw him, more and more of them took up Gill's template. The result was a deluge of sober, eminent, sphinx-like heads – many of them unattached to human frames. Thus reduced to a giant, bodiless brain, Hugo resembled something out of a ghoulish B-film.

His symbolic beheading, however, suited the moment. For, by 1870, French current events were no laughing matter. Napoleon III's Second Empire ended in a war, one that saw Paris besieged and starved into submission. Her defeat was followed by the Paris Commune, which terminated with a historic bloodbath. More Parisians lost their lives in its "Semaine Sanglante" (Bloody Week) than had done so under the Reign of Terror. Much of the city was also torched, including the Tuileries Palace – never to be rebuilt – and the capital's City Hall.

These upheavals led to yet more censorship, rules so strict they drove André Gill to gloomy sketches such as L’enterrement de la caricature ("Caricature's Funeral") and Produits de la censure ("The Products of Censorship"). In the first, Gill and a fellow artist trail behind a hearse. In the second, a headless, legless artist is being served up on a platter – with his drawing tools lashed to his back.

Just as he had promised, Victor Hugo did return. At the end of the Second Empire, he was greeted as a deity. But, after the Commune, his politics rapidly attracted new hostilities. The difference was that, this time, they came from Catholics and right-wing monarchists. Yet Gill's admiring image, that of a new Sun King, stubbornly endured. Progressively, cartoons of Hugo grew less and less deformed. The ceaseless self-publicist became a noble patriarch, surrounded by symbols like lions, crowns and lyres. When he finally died, in 1885, the Panthéon was once again reclaimed for his burial.

Shows such as Caricatures: Victor Hugo and Page One are truly useful. They provide a chance to see pivotal works by talents who, if not forgotten, are rarely shown in context. For, despite their contributions, it's usually as if artists such as Dantan and Benjamin never existed.

An additional problem is that, during the 19th century, caricature could be a brief career. Few devoted their lives to it as did Philipon and Daumier. Many artists, like Gustave Doré, turned to illustration. Others were simply unlucky. Grandville, although consistent and successful (he produced over two hundred albums), was destroyed by a series of family deaths. Beset by mental problems, he died at only 44. André Gill, too, ended life in a mental home. Just like Nadar, Etienne Carjat (1828 – 1906) switched to photography.

In 1840, after a decade with Philipon, Benjamin Roubaud moved to Algeria. There he became a correspondent for the bigger, better-paying L'Illustration. Although Roubaud continued drawing caricatures, he was dead by the age of 35.

Such artists fed on the vanities of men like Hugo. Yet they were also focused on ordinary people, capturing their quirks and habits – interpreting their modern "types." From waiters to workers, their comic attentions promoted the average citizen. This new, modern pantheon was not lost on fellow artists. The Impressionists (who held their first show in Nadar's studio) soon transformed it into "higher" art.

The right to ridicule which caricature defended is still central to French society. Viewed as both resistance and opposition, mockery is also seen as a voice for the "little man". (The memory of those workers scrawling pears on the wall still lives.) Yet the right to deride remains indivisible from its tortured history. As with the separation between church and state, the French fought long and hard for their press freedom. In many of the battles, caricature was central.

Right after the 2015 murders at Charlie Hebdo, the Ministry of Education raced into action. They produced a special guide to French caricature, one that reprised its history and discussed its strategies. This kit, which came with detailed teaching tools, was prefaced by the words: "Caricaturists of the press are both artists and journalists, who wield a weapon of concision… Students may find such a coded genre difficult. But French caricature is a Republican tradition and one protected by the law of 1881."

Victor Hugo never denied an artist the right to mock him. Even when he was most derided, when censorship made it easy, this egomaniac author sided with his critics. "The diameter of the press," he said in a famous speech, "is the diameter of civilization. Every diminution of its liberty is succeeded by a diminution of civilization… I know, gentlemen, that the press is hated, and that is my great reason for loving it."

• Caricatures: Victor Hugo and Page One runs through January 6, 2019 at Maison Victor Hugo

The show's excellent catalogue is bilingual, in both French and English.

• Another wonderful exhibition, The Nadars, runs through February 3, 2019 at the Bibliothèque François Mitterand. It features the Panthéon Nadar and a number of caricatures as well as photographs of Gustave Doré, Charles Philipon, Daumier, etc.

There is also a virtual version online.

• In February 2019, The University Press of Mississippi publishes the first book on the artist Cham (Amedée de Noé), by the comics scholar David Kunzle