The experience of reading about Grant Morrison's comics is frequently more stimulating than actually suffering through the work itself. In undertakings like The Invisibles or 7 Soldiers, Morrison slaps together elaborate sagas that span volumes, centuries, and dimensions, ganglial constructs that weave themselves around grand themes like time, language, identity, and heroism. The elegance with which some brave souls like Douglas Wolk and Marc Singer have untangled and explicated this mess can situate readers at an appealing remove, surveying Morrison's story-worlds from the kind of extra-temporal, fifth-dimensional vantage point one might expect to find elsewhere in the author's sub-Dickian oeuvre. But this critical distance too often simply amplifies the spiralling, vertiginous feelings of idea-rich complexity that Morrison is everywhere at pains to induce, and ignores the hollowness that resounds at the work's core.

The experience of reading about Grant Morrison's comics is frequently more stimulating than actually suffering through the work itself. In undertakings like The Invisibles or 7 Soldiers, Morrison slaps together elaborate sagas that span volumes, centuries, and dimensions, ganglial constructs that weave themselves around grand themes like time, language, identity, and heroism. The elegance with which some brave souls like Douglas Wolk and Marc Singer have untangled and explicated this mess can situate readers at an appealing remove, surveying Morrison's story-worlds from the kind of extra-temporal, fifth-dimensional vantage point one might expect to find elsewhere in the author's sub-Dickian oeuvre. But this critical distance too often simply amplifies the spiralling, vertiginous feelings of idea-rich complexity that Morrison is everywhere at pains to induce, and ignores the hollowness that resounds at the work's core.

The perfect picture of this kind of strenuous vapidity occurs in Doom Patrol, in an issue where a character flexes his biceps so hard that he turns the Pentagon into a circle: certainly this is a feat comparable to revivifying a moribund superteam franchise (JLA, X-Men), or crowbarring a slew of not-ready-for-primetimers into their own ramshackle epic (7 Soldiers). But what the hell is the point? Morrison, like his character Flex Mentallo in that earlier comic, may succeed for a moment in changing the shape of the system, but the rules by which that system operates, the things it stands for, remain forever unaltered. Flex's new Pentagon, like Morrison's new conception of the superhero, ends up circling a big empty nothing—though there sure is a lot of impressive-looking flexing involved.

Flex's own series marks an opportune point from which to examine the Morrison method in greater detail, not least because the author himself argues for the pivotal role it plays in his career. “Flex Mentallo made me think about new ways of writing American superhero stories,” he says, at the same time that it “hinted at the age beyond the Dark period.” Its recent republication, too, cannot help but invite new comparisons with the fifteen years of Morrison comics that follow in its wake. And Flex Mentallo does resemble other Morrison comics in its precarious architecture, so that it may indeed sound intriguing once mapped out. But permit me not to do the book a disservice and ignore the clumsiness with which its author bulls through his thematic concerns: if here there be marvels, they are flimsy and fleeting, without exception.

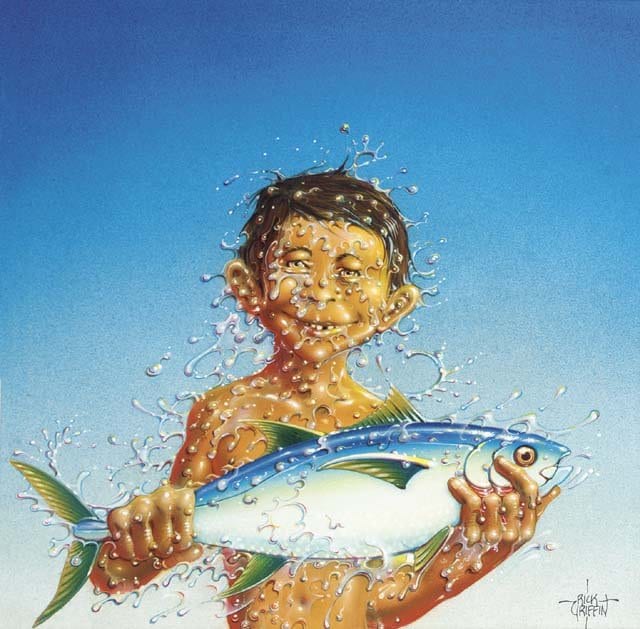

First published in serial form in 1996, and only now collected after years of litigious handwringing, the book has its origins in a send-up of the famous Charles Atlas bodybuilding ads—surely the least of the many parodies that ur-text has inspired. Where Chris Ware satirizes the ad's ugly power fantasies, and Leonard Cohen's Beautiful Losers mines it for its sexuality, Morrison simply makes a man out of Mac by turning him into a superhero. The newly rechristened Flex Mentallo—whose superpower is basically that he has muscles, which almost qualifies as a clever conceit—lends a hand to the Doom Patrol in a couple escapades like that Pentagon outing, but here in his own title Flex is no longer a character who has adventures, so much as he is a locus for all things superheroic, and Morrison's meditations on the same.

Flex Mentallo is essentially metafiction, full of the pervasive and winking reflexivity of other Morrison series like Animal Man—which used a Wile E. Coyote pastiche to reprise Duck Amuck's notion of cartoonist-as-god, much like Flex's take on the archetypal comic book ad spins off into investigations of the comics reading experience. Here, as Flex searches for a group of mysterious terrorists called Faculty X, as well as an old comrade in arms, the narrative dizzyingly shifts register between Flex's flatfooting and several other levels of reality and perception. In one, Flex exists only in the childhood scribbles of Wally Sage; in others, Sage may or may not be an angsty rockstar, an angsty adolescent, an alien abductee, a powerful psychic, a 1960s Greenwich Village scenester, or Flex himself. Sage may also be hallucinating the entire story as he dies in an alleyway—or maybe he's on his kitchen floor, who knows. Wally Sage's suicide and Flex Mentallo's quest, however, soon begin to converge as it becomes apparent that in both endeavors the fate of the entire universe is at stake. As the storylines flit back and forth—now in a fishbowl, now in quantum subspace; here in a council flat, there in a nuclear flash-fire—Morrison attempts to tie all these elements together in a grand unified theory of comics, if not of existence. Nothing if not ambitious, the series opens with a big bang, and plunges forward toward a looming apocalypse, with each of its four issues loosely aligned with one of the “ages” of comics fandom (Golden, Silver, “Dark”...), as well as the stages of young Wally's life.

So far, so good, right? Scope, complexity, ambition—all the hallmarks of a potentially expansive SF experience. But despite the abstract appeal of Morrison's ideas and approach, there is very little enjoyment to be had in their execution, not least because he assails his readers with verbiage at once high-flown and ham-fisted. The Morrison touch—deployed everywhere, endlessly—is to crowd one high concept after another, reverently leaving each alone, never to return to any one idea again. The technique works well enough when trying to gesture toward a vast back catalogue of adventures for Flex, so that a panel featuring an exploit with “Origami, the Folding Man,” leads into other enjoyably spurious antics with “the Lucky Number Gang” or “the Baffling Box,” in one of the comic's few successful homages to superhero nonsense. But too often Morrison tries to convey a sense of unearned wonder by spilling out vagaries in overheated prose, adopting an awestruck tone and asking his readers to “imagine” half-baked fantasies that seem rescued from Burroughs or Ballard's litter bins. “Candy-striped skies!” the TV says at one point to a pensive Flex. “Can you imagine? And a child smiling, weightless—each floating strand of hair with a tiny eye at its tip. A swaying mass of blinking lights.” Elsewhere, we're invited to admire a superhero utopia of bullshit portmanteaux—“Dreamatrons and boom shoes, paraspace-suits and omniscopes”—or to marvel at the experience of “Breathing the narcotic vapors of spectral avengers, inhaling ghost girls[...].”

These visionary moments are too often hypothetical, too seldom committed to and drawn out. But what's worse, they're derivative, too: one character, confronted with the cosmos, actually gives voice to the sentiment that we're all “like ants... just ants.” Morrison's mouthpieces in the story, though, contend that such cliché revelations are on the contrary dangerous and revolutionary. The book begins with a police lieutenant transparently explaining for us just how crazy and subversive Morrison's ideas really are. The terrorists that Flex is searching for, he says, leave cartoon bombs in crowded public places to “show us how fragile the whole system is,” to “damage the foundations of the establishment.” Morrison seems to think that, like the characters he's created, he too is leaving these cartoon bombs in the middle of a system that could use some shaking up—the very funnybook you hold in your hand will change the course of comics forever! Like the useless plastic bombs of his characters, however, Morrison's, too, are duds.

Where Morrison's efforts fail to fulfil the potential of their design, the same can't quite be said of Flex's artist, Frank Quitely. One of Flex Mentallo's other attractions is its status as the first major collaboration of Quitely and Morrison, a team who would go on to make extremely entertaining popcorn comics, especially with the slick and quick We3. Quitely in particular would distinguish himself in those later works, perfecting a brand of freeze-frame action-adventure that tips the scales away from Morrisonian fustian and towards the purely visual. Surely the strongest sequences in the Morrison/Quitely canon are those where Morrison writes the least: the potted origin story that leads off their Superman, the silent psychodrama that takes up an entire issue of New X-Men, the video screens and savage attacks of We3. (Indeed, We3 offers convincing evidence that Morrison may work best when he limits himself to penning lines like “Gud dog.”)

As we might expect, though, Flex's Quitely is not yet as restrained as he is in those later works, not as classical, not as much himself. When his figures here aren't squishy and unbelievable, they're over-proportioned instead—Flex looks less like a barrel-chested musclehead than he does a parade balloon about to pop. The artist hasn't yet discovered his own clean and clear style, or learned to resist all the sturm und drang that beset modern mainstream comics—reckless camera angles abound in Flex, as do panels that bleed pointlessly to the book's edge, millions of wispy details, and characters who mug and pose rather than live their lives on the page. That said, the art is one of the only things to recommend the comic. The character design is sometimes inspired—the drippy, tacky Waxworker is a sight—while Quitely's vaunted ability to depict trumpery, fabric, and flesh as tactile objects does manifest itself on occasion. As Flex, for example, descends into a superhero orgy, in one of the book's most ill-considered developments, the artist abstracts the scene into a closely cropped image of faceless limbs and skin impossibly entwined, a panel that is suggestive and unexpected in its reticence. Too bad that the script, characteristically, robs the art of its accomplishment and poetry, pasting over it a humdrum evocation of superhero fetishism: “Imagine vampire amazons in wetlook thongs... a shy secretary stripping down to her black vinyl costume... gunsmoke and spent caps and Multiboy in his new fucking costume!”

I'd really rather not imagine all that, thanks. Such notions were infused with more scandal and panache when the Tijuana Bibles first trotted them out a lifetime ago. But the scripting problems aren't limited to the bankruptcy of the ideas dropped here and there like so many rabbit pellets—even the overarching structure, so impressive from a distance, is fundamentally corrupt. Consider the book's principle of organization once more, where Morrison increasingly equates the proliferation of bad superhero comics with the end of God's green earth. So the first issue corresponds to the big bang, Wally Sage's childhood, and the Golden Age of comics, and each subsequent chapter marches forward until we reach armageddon, Sage's eradication, and “the first ultra-post-futurist comic” wherein “characters are allowed full synchrointeraction with readers.” Comics are life, in Flex Mentallo; the two are coterminous—a sentiment with which I can find great sympathy, given how lousy with comics my own life is. The crucial problem with Flex Mentallo is that Morrison's idea of what comics are, and what life should be, are both irremediably, impossibly benighted.

Comics, for Morrison, mean superheroes, and life seems to mean something equally cartoonish. Wally Sage, the lieutenant, and Flex himself all constantly hold forth on the state of the world in general, and the superhero in particular—why they do so is anyone's guess, since their ruminations never seem provoked by anything other than a whim of the script. Sage especially indulges in tiresome laments for the “good old days” of comics, the prelapsarian golden age of “when you're a kid,” when superheroes “loved us,” when we could “look up to” them, when there was no use wondering “who always saves the world?” because the answer is always, and reassuringly, “Superheroes, that's who.” Flex Mentallo, and Wally Sage, seem traumatized by Crisis and Doomsday, Liefeld and Shadowhawk, so I suppose it's possible to forgive Flex's often elegiac tone, its rosy-eyed nostalgia. Let's even grant that in such a context, proclamations like “[superheroes] abandoned us, left us to die” may not sound risible, or it might not be asinine to say that “all the heroes are in therapy and there's no one left to care about us.” There's still no excuse for a hunched over, defeated-looking Sage to mewl, “Why didn't the superheroes save us from the fucking bomb? ... Why didn't they stop my mum and dad fighting?”

Even if we're charitable enough to write off such prattle as the mawkish dying words of a suicide—Wally Sage spends the book medicating himself to death, after all—we would have to contend with the comic's concluding, and by all indications heartfelt, sentiments. “We can be them,” says Sage, after the superheroes reveal the secret of the universe to him. Soon after, Flex echoes that huckstery Atlas ad copy: “I can show you how to be a real man,” says the superhero, hand outstretched manfully to scrawny Wally Sage. Superheroes as moral exemplars, as platonic ideals, as fiction bombs left latent in our universe and which will one day explode in blinding blazes of inspiration and mass perfection: does Morrison actually believe this cack?

Its seems, regrettably, so. Nowhere, in Flex or elsewhere, is there a world beyond the superhero for Morrison—there's only Our Benevolent and Perfect Role Models, or there's some ineffable beyond. In Flex, our reality has been constructed (and botched) by Nanoman and Minimiss, just as in All-Star Superman, there's only Superman's world, or the world he deigns to create for us, where our lives are no more than little experiments. If such a comic-book reality is unacceptable, though, we can escape it, don't worry: but the only escape is oblivion. So characters in Flex experience their moments of cheesy, drug-induced cosmic awareness as blanched-out obliteration, just as The Invisibles will later dissolve into panel-less whiteness. Not much imagination goes into what life, or comics, might be like outside of the gleaming standards superheroes have erected for us. The closest we get to reality, in Flex Mentallo, is a morose rockstar, strumming on his acoustic; the comic's idea of real life is a relationship in which your girlfriend, clad perpetually in a clinging tube dress, nags you so much that you forget how much you love her, man.

Even shorter shrift is given to “adult” comics (by which I can only guess Morrison means to indicate undergrounds—the book provides scant details). These are apparently even more morally corrupt and baneful than the plague of dark superheroes. Not only do they fail to deliver young Wally Sage any kind of moral compass—in their pages, “Nowhere was safe. There was no one you could trust”—but they also fail to inspire any kind of ennobling activity, other than a quick wank. Says Morrison through Wally, his proxy, “I knew I shouldn't have read those 'adult' comics.” So much for the source of every major aesthetic achievement in comics over the last half century.

Given how grievous are the rest of these sins, to complain about the book's repackaging may seem like mere pettishness. But the comic's fundamental faults are carried out even here. Besides some superfluous sketches and original art pages from Quitely, the “deluxe”ness of this edition consists mainly in some updated hues. The new color job turns a Silver Age villain, motley-colored in the original, into dead, dull gray; it takes those moments of oblivion and transcendence and stains their pure fields of whiteness with urine-yellow gradients; it leeches any trace of four-color revivalism out of the original, leaving the “deluxe” version looking grimy, befouled, and drab. As distasteful as that sounds, this is actually a more truthful rendering of what Morrison and Flex Mentallo actually do: purporting to bemoan the darkening of superhero stories, to embody a new standard for inspirational comics, they in fact indulge in all the grim unpleasantries at which they tsk so self-righteously.

So, yes, the principles voiced everywhere in Flex Mentallo would have us disapprove when superheroes shrug off genocide with a joke (New X-Men), when Kirby characters get murdered just so the plot has a MacGuffin (Final Crisis), when porn sites pop up devoted to teenage girl heroes (7 Soldiers), or when a villain tortures his victims before performing invasive surgery on their faces (Batman and Robin). Flex and Sage would shake their heads in dismay—and Morrison would follow through with it all anyway. Perhaps, then, the new tones in this edition of Flex can likewise re-color our understanding of Morrison's past decade-plus. We can see now that Flex Mentallo, like Morrison's comics in general, trades in the same ersatz grown-uppedness that it protests in other comics. Morrison's comics have never been ben-day bright; in the end, like Flex Mentallo, they've always borne that undercoat of ugly Vertigo gray. That's what lies at their center—and that, at last, is all there is.