[Click here for Part 1]

[Click here for Part 1]

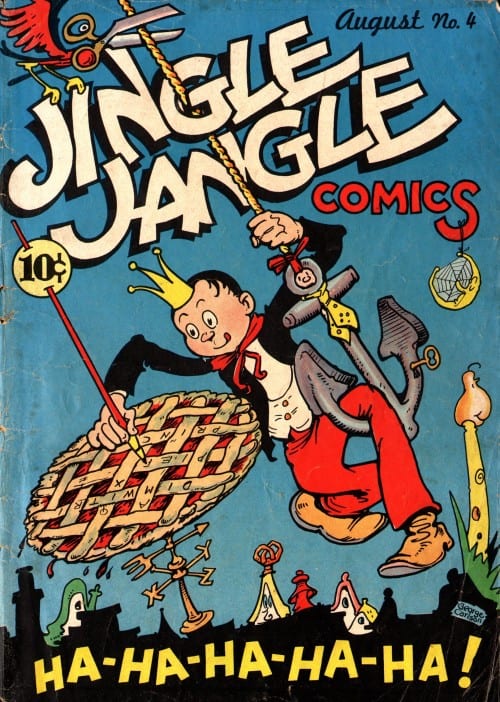

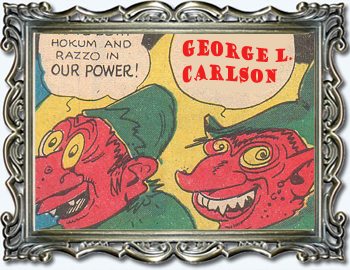

In the 1940s, artist, designer, and puzzle-maker George Leonard Carlson (1887-1962) created a series of about 80 comic book stories that are as playful, surreal, and representative of a fully-realized singular vision and style as the much more well-known and adored books by Dr. Seuss. For years, very little has been known about the life and work of the artist who made these extraordinary comics. Thanks to the Internet and the work of obsessive, data-mining comics historians, it's become possible to at long last figure out the puzzle-maker. In December 2013, a book will at last be published on this under-appreciated master: Perfect Nonsense: The Chaotic Comics and Goofy Games of George Carlson by Daniel Yezbick (Fantagraphics). From all indications, Yezbick's book offers a satisfyingly comprehensive and insightful study of George Carlson's work. It is hoped that these columns will help generate interest in the forthcoming book and George Carlson -- his work has much to offers to readers and artists today.

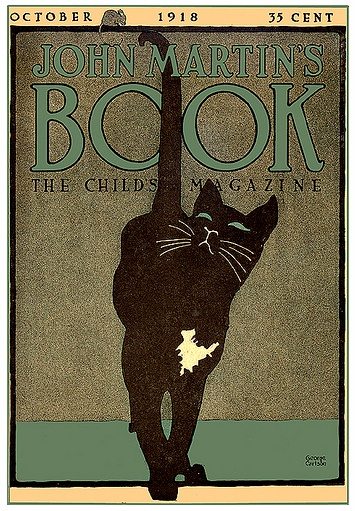

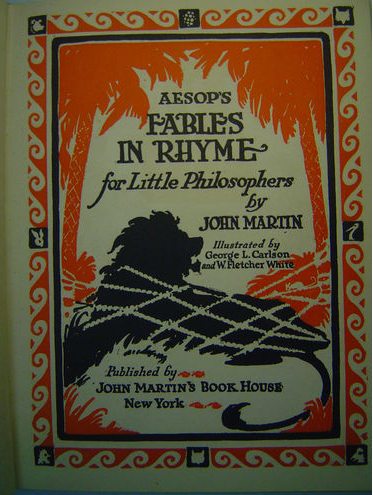

Part one of this article presents some biographical details, and brief looks at Carlson's early comics, his notable work for the children's publisher John Martin, and the many books adorned with his illustrations and covers. This conclusion to the piece offers a survey of books authored by Carlson, a look at his virtually unknown newspaper comics, and a short study of his seminal comic book stories which can be seen as the culmination of the long and varied career of an inspired graphic artist/cartoonist.

Books by George Carlson

In addition to producing outstanding illustrative art for books by others, George Carlson also authored a small library of books himself. Nearly all of these titles fall into one of three categories: activity books for children, how-to books on cartooning and drawing, and compilations of jokes. Carlson apparently did not view himself as a prose fiction writer, so his books mainly serve as platforms for his graphics and games. Considering the accomplished surreal playfulness of his Jingle Jangle stories, one wonders what a children's storybook, or a novel by George Carlson would be like.

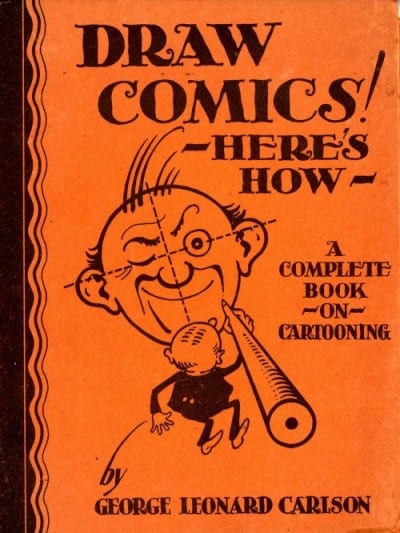

Aside from his 1922 Peter Puzzlemaker book which he created for the visionary children's publisher John Martin (see Part One of this piece), Carlson's first significant book is Draw Comics! Here's How!, a stylish hardcover volume published in 1933 by Whitman that offers practical lessons and tips, splendid examples of Carlson's cartooning, fun comics and cartoons, a dose of casual racism (typical in American comics for the time), and frank discussions of the cartoon craft and industry.

Carlson's guide has been reprinted by Dover Books and remains in print (and pixel, being available in a Kindle edition as well). The book even snuck into a 2009 retrospective exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit in 2009 when it was included in "Art Spiegelman: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!."

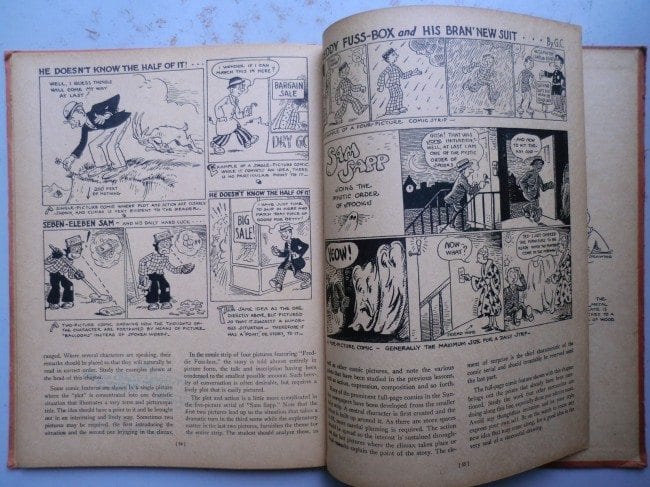

Carlson's love of cartooning and comics comes through in every page. Published just before the emergence of the comic book, it is focused on developing short versions of the form that can be sold to magazines, newspapers, and advertisers: gag panels, strips, and full-page Sundays. Carlson's advice in the book is perhaps the most personal statement on his own craftsman-like approach to graphic arts that exists: "Aim first for quality, as speed develops with experience. Patience, practice, and perseverance, together with a spirit of happiness in one's work are bound to bring the rich rewards that a world of opportunity offers."

It is interesting to note that, as far as we know, when he penned Draw Comics! - Here's How! in 1933, Carlson had not actually created sequential graphic narratives professionally since his 1913-1916 Film Fun funnies (see part one of this article). It seems likely that working on his 1933 guide to drawing comics that got Carlson thinking once again about comic strips. Indeed, Draw Comics! - Here's How! includes several examples of cartoons by Carlson, including a full page Sunday-style comic called Superstitious Sidney.

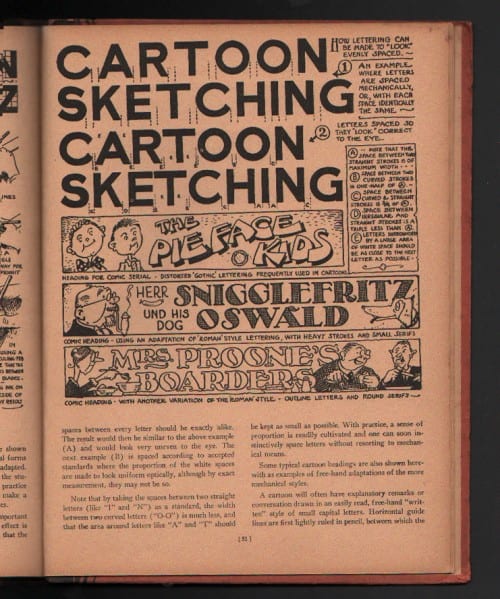

George Carlson, like many artists with well-developed bodies of work, was a bit a of magpie of concepts, picking up ideas and approaches and never quite letting them go. For example, on page 51 of his how-to manual, Carlson demonstrated approaches to lettering in comics. It's revealing to note that he includes in his examples a header entitled, "The Pie-Face Kids." Seven years later, Carlson would use a similar name for his longest-running series, "The Pie-Face Prince." One wishes Carlson would have developed comics from the other headers presented on this page: "Snigglefritz Und His Dog Oswald" and "Mrs. Proone's Boarders."

Carlson re-visited the idea of a cartooning manual four years later with Points On Cartooning and How to Draw Funny Pictures (1937). It appears to have been the first of several books he compiled and illustrated for Treasure Chest Publications. The typical Treasure Chest format appears to have been a larger-size, staple-bound book employing the dimensions of sheet music (indeed, several of Carlson's book for them were collections of sheet music adorned with his illustrations). The cover of Points features a classic full-color painted cover by Carlson.

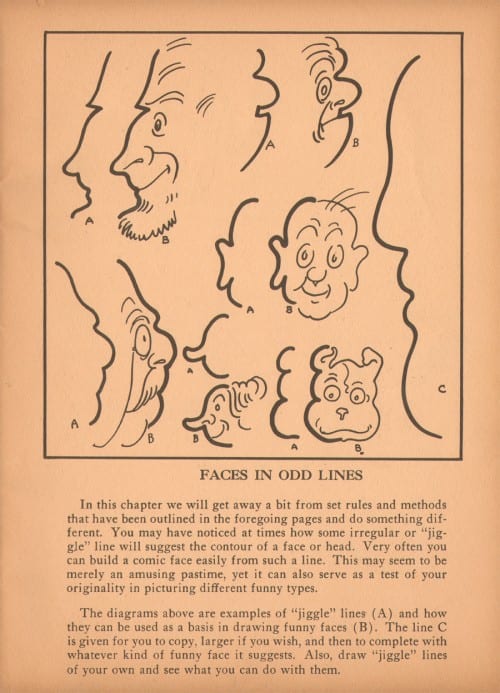

Among the interior lessons is a page derived from his co-creator John Martin's free-spirited "jiggle-line" approach to cartooning. The idea is to draw a jiggled line and then develop a cartoon that incorporates the line. Martin Gardner, in his essay, "John Martin's Book: A Forgotten Children's Magazine" (reprinted in From the Wandering Jew to William F. Buckley (Prometheus Press, 2000), writes of John Martin, “When he was with children he liked to ask them to make squiggly lines on paper while he jiggled their elbow, then he would add more lines to create what he called a ‘quiz-wiz’ animal.” It seems that Carlson not only included this technique in his work, but also thought enough of it to teach it to others. In his Jingle Jangle stories, Carlson would apply the spontaneity of this approach to narrative as well as visual art. In his instructional text, Carlson calls the "jiggle-line" exercise a test of originality -- telling words from an artist who created some of the most original comics of his era!

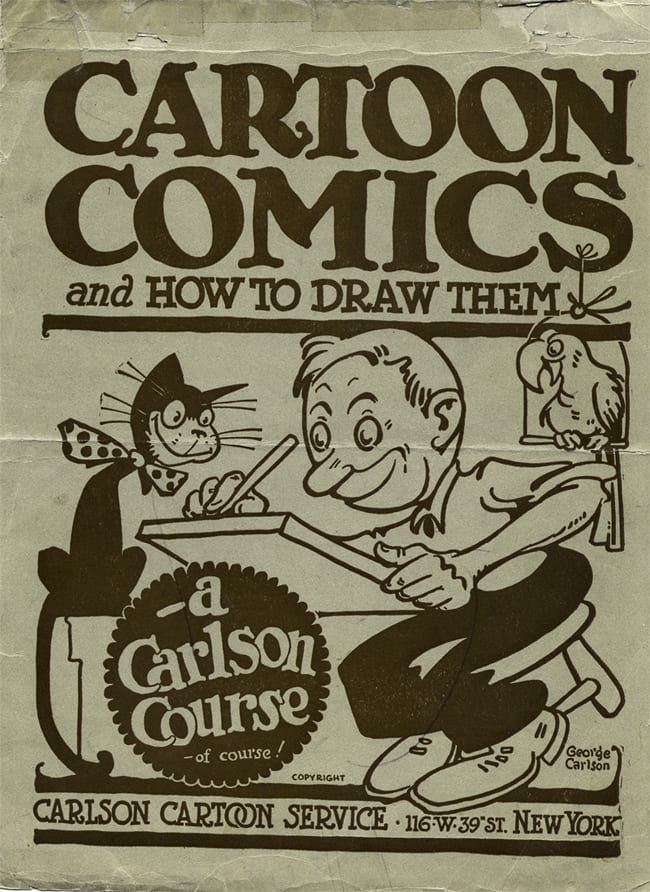

At some currently unknown point, Carlson also created and offered "Cartoon Comics and How to Draw Them," a correspondence course in cartooning (with the playful subtitle, "A Carlson course -- of course!"). Danny Ceballos has in his collection the cover of one of the lessons (sadly, the contents were missing), with the comment: "Imagine the lucky fellow who got to take that course!" Danny also suggests that this art might include a cartoon self-portrait of Carlson (compare with his photo in "Figuring Out George Carlson, Part 1").

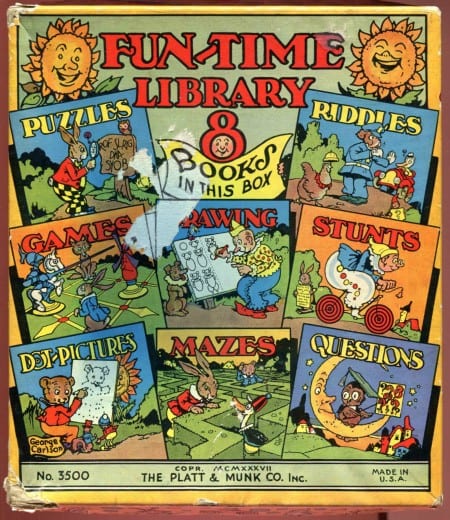

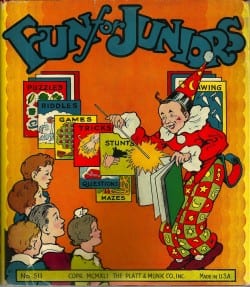

Carlson authored a series of clever, attractively drawn children's activities books for Platt and Munk in 1937. All of these include the phrase "fun-time" in the title (echoing back to his 1923 activity for John Martin book Some Fun to Make Book), such as: Fun-Time Puzzles, Fun-Time Riddles, and Fun-Time Questions. There's no doubt that, in creating these books, (three of which were re-issued in a boxed set as Fun-Time Library in 2008 by Green Tiger Press), Carlson was drawing from his twenty years of work in children's magazines. It seems that Carlson knew what he doing, as it is hard to find copies of these books which are not drawn in, colored, or otherwise altered as directed (my copy of Carlson's 1922 Peter Puzzlemaker has a half-page cut out and glued to the back pages, as Carlson advised his readers to do in the book's prefatory note).

As with the Uncle Wiggly books, Carlson appears to have conceived of the series as volumes that could be sold individually and as a boxed set (with his art adorning the box, as well). This ingenious approach must have worked out well for the free-lancing Carlson as he scored multiple book projects off of one pitch.

On addition to his 1937 Fun-Time, and 1939 Uncle Wiggly boxed sets, Carlson also authored in 1938 an ingenious boxed set of 10 small books called Paint Without Paints. A brush dipped into water and applied to the pages in these books will magically color the black-and-white images, all of which are drawn by Carlson. The themes of the various books reflect many of the interests and pet subjects of Carlson's career: Transportation, Objects, Storybook Friends, Toytown Holidays, etc.

Through 1950, Carlson regularly authored books, mostly illustrated compilations of jokes and various activity books. It appears that, towards the end of this run, he unsuccessfully pitched a storybook with writing and illustrations by him that would have been based on his Lewis Carroll spin-off, "Alec in Fumbleland."

Alec was a feature in the two issues of Carlson's 1946 comic book title, Puzzle-Fun Comics published by George W. Dougherty. (Carlson seemed particularly keen on using the word "fun" in his titles for a while).

In comparing his three big Platt and Munk projects of 1937-1939 -- Fun-Time Library, Paint Without Paints, and Uncle Wiggly (see Figuring Out George Carlson, Part One)-- we see Carlson masterfully employing a variety of styles and approaches. While producing a prodigious amount of top-notch work, Carlson draws from his deep background in creating activity pages for children's magazines and from his work illustrating children's literature to create a small library of hip, savvy books that continue to hold appeal for young readers today.

The Love Child of Nancy and Smokey Stover: George Carlson's Little-Known Newspaper Comic Strips

"You make me dizzy Miss Lizzy..."

(Larry Williams, 1958 and covered by The Beatles in 1965)

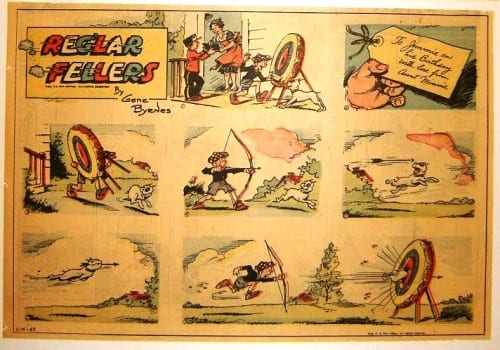

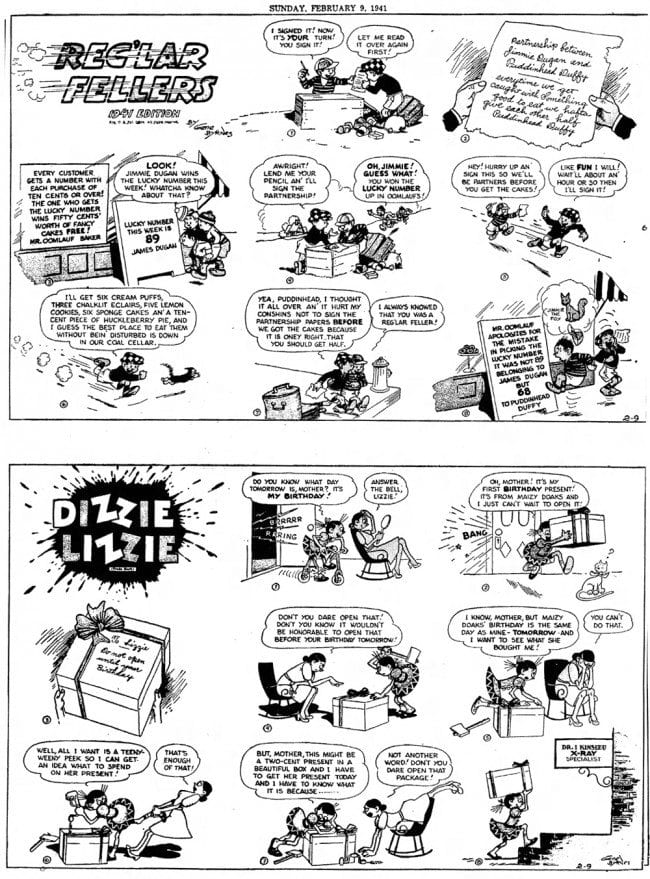

On the heels his intense run of work for Platt and Munk at the end of the 1930s, Carlson must have been ready to saunter forth in a new direction. Perhaps the two manuals on cartooning that he authored in the 1930s reminded him of how much he loved comics and cartooning. Or, perhaps he had some sort of connection to New York-based cartoonist Gene Byrnes, creator of the long-running daily and Sunday newspaper kid comic strip, Reg'lar Fellers (1918-1949).

According to author, comics historian and fellow TCJ columnist, Ron Goulart, "Carlson had a long and anonymous association with Gene Byrnes. He helped out on Reg'lar Fellers on several occasions and from the early 1940s to the end of the strip he ghosted it entirely." (The Encyclopedia of American Comics edited by Ron Goulart, Facts on File, 1990).

Indeed, a quick study of Reg'lar Fellers Sundays and dailies from the 1940s reveals the unmistakable grace and the trademark vignette-style compositions of George Carlson's hand.

A November 11, 1948 Reg'lar Fellers daily also shows Carlson's style in both art and writing. In this example, Carlson plays with one of his pet subjects - Christmas and Santa Claus.

It's impressive to realize that, while he was authoring his seven-year run of brilliant Jingle Jangle stories, Carlson also ghosted a newspaper comic strip!

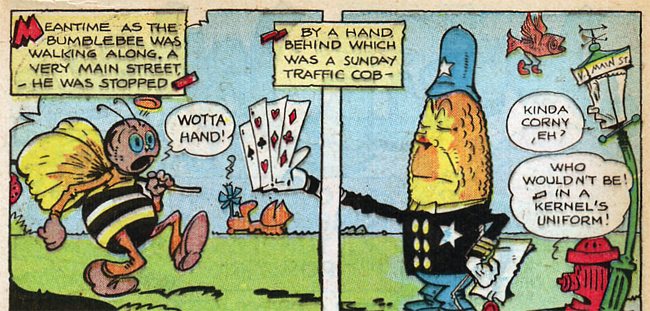

Carlson, working anonymously, was obliged to preserve the general visual look and tone of the well-established (and beloved) strip. However, in 1940, around the time he took over the Reg'lar Fellers strip, Carlson created Dizzie Lizzie, which ran as a "topper" strip on the Sunday page. In the 1940s, it was common practice for syndicates to require their artists to break up their Sunday comics pages into two strips, so they could pitch subscriber newspapers that they were providing twice as many comics for the price. It also allowed newspapers to drop the topper for more lucrative advertising sales and still be able to run the anchor strip -- a situation which often occurred, making it very challenging today to locate complete runs of toppers.

The topper strip allowed many artists who were locked into certain successful concepts to break out and try new ideas. There is a tremendous amount of vitality and innovation buried in these little-known, hard-to-find comics. Sometimes, the results were better than the anchor strip, as with Gene Ahern's topper The Squirrel Cage, which ran with Room and Board (a terrific screwball comic in its own right). A compilation and study of the American topper comic strip is long overdue, and is being lovingly assembled and designed for IDW's Library of American Comics by Dean Mullaney.

In the case of Carlson, a topper strip, because it was not bound to a template created by a previous artist, allowed him to work in his own style. As Ron Goulart observed about Carlson and Dizzie Lizzie, "... he made no attempt to disguise his own style; although it was signed Byrnes, it was unaltered Carlson." And what a style! Born from nearly thirty years of intense graphic production, Carlson pulled out all the stops in his half-page comic strip about a very odd, very funny little girl. Carlson was perhaps inspired by Little Lulu, the hit panel comic about a single-minded, spaghetti legged, quirky young girl in a short dress that appeared regularly in the Saturday Evening Post by Marjorie Henderson Buell (the comic book version of Little Lulu by John Stanley did not begin until 1945, five years after Carlson's Dizzie Lizzie).

George Carlson's Dizzie Lizzie newspaper comic strip is the secret love child of Nancy and Smokey Stover. Working within the medium of the newspaper comic strip, Carlson fashioned Dizzie Lizzie to be compressed and contained where his later Jingle Jangle comic book stories are meandering, free-spirited, and chaotic. For the short period of the strip's life (it lasted less than two years) Dizzie Lizzie offered a head-spinning diet of pure, joyous screwball comics. Carlson packed the panels with background gags, visual puns, and just plain nutty stuff, such as the curly sink faucet and paint-brush sized toothbrush in the October 6, 1940 episode (seen in panel of the example above). In other strips, telephone tables patiently cross legs while Lizzie chats, butterflies hold up cat's tails (sporting a Bill Holman bandage), and so on. These juicy details would soon take center stage in Carlson's comic book work.

In Dizzie Lizzie, Carlson's main gags were also often quite funny and off the wall. In this strip that reads as an inverted Winsor McCay Dream of the Rarebit Fiend comic, Carlson shows perfect pacing and comic timing.

The drawings of Lizzie devouring a half-turkey, a massive bowl of rice pudding, some apple pies, and a bunch of bananas as a "little" bedtime snack capture the character's supremely self-confident attitude in a richly funny way. (It seems Lizzie is Lulu and Tubby rolled into one character).

Lizzie is an extremist. At times, Lizzie's character seems happily sweet, and at other times, as in the March 23, 1941 episode, she is comically violent as she psychotically destroys a feather duster. The action is all framed in Carlson's trademark vignettes, similar to the one he created for the cover of Margaret Mitchell's novel, Gone With The Wind.

While the main gag in this episode may not be particularly amusing, one can find much to appreciate in Carlson's fabulous cartooning chops and in the screwball background gags, particularly with the entertaining cat. It's highly likely that Carlson was also influenced by Bill Holman's screwball comic strip, Smokey Stover, which began in 1935 and was stuffed with similar types of gags. The personification of the radio in this episode, however, is pure Carlson, and broadcasts loud and clear the astounding direction his comics would soon take.

The Jingle Jangle Morning - Carlson's Remarkable Comic Book Work

Although largely unknown to the general public, Carlson’s Jingle Jangle work is highly regarded by a select few. Over the years, various collections and magazines have re-published some of these stories, including:

- The Smithsonian Book of Comic Book Comics by J. Michael Barrier and Martin T. Williams (Smithsonian, 1982)

- The Comics Journal #263 (October-November, 2004) - Five stories are reprinted in full color, with a brief introduction by Dirk Deppey

- Art Out of Time: Unknown Comics Visionaries, 1900-1969 by Dan Nadel (Abrams ComicArts, 2006)

- The TOON Treasury of Classic Children’s Comics, edited by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly (Abrams ComicArts, 2009)

- The Golden Collection of Krazy Kool Klassic Kid's Comics, edited by Craig Yoe (IDW, 2010)

Presumably there will be more of Carlson's Jingle Jangle stories offered in the upcoming Perfect Nonsense: The Chaotic Comics and Goofy Games of George Carlson by Daniel Yezbick (Fantagraphics, December 2013).

Perhaps the most famous writing about Carlson's work is “Comic of the Absurd,” Harlan Ellison's essay published in All In Color For A Dime, the 1970 anthology of original essays about golden age comics. In the essay, Ellison sidestepped his way past the gooey trap of nostalgic reverie that ensnared most of the other essayists in the book (as well as much of 1970s America)

Ellison’s essay praises Carlson’s Jingle Jangle stories for what they offer in the present – not the past, calling them “unparalleled contemporary fables,” and referring to Carlson himself as “Samuel Beckett in a clever plastic disguise.” Ellison's description of Carlson's Jingle Jangle style employs wordplay that mirrors its subject: "...jumbled and overlapping shapes that delightfully bedevilled the reader... fats and thins that gamboled and bumbled everywhichway... plot lines surfeited with double-level puns."

Ellison – a star science writer in 1970 -- began his essay, “Comic of the Absurd,” by picturing the world a mere 785 years into the future, “when the aliens come from Tau Ceti in 2755 A.D. and begin scrabbling like dogs digging bones, in the rubble that is left of Civilization As We Know It.” Ellison postulated that Carlson’s art would be highly revered by the future alien visitors, along with Bosch, Van Gogh, Vermeer, and Dali. Considering what we now know about Carlson’s work preserved in (and in some sense defining) the Crypt of Civilization – something Ellison appears to have not known about in 1970, when he wrote about Carlson (Ellison wrote about Carlson again, in “Roses In December,” his introduction to the 1990 Carlson tribute comic book published by Innovation, Mangle Tangle Tales #1) – Ellison’s futuristic, fanciful opening may prove to be more correct than the author originally realized.

By the time he put pen to paper and created the Jingle Jangle stories, Carlson had already published hundreds, if not thousands of innovative pieces of commercial illustration and cartooning. A consideration of this remarkable body of work wrenches Carlson’s comic book work from comics history into a much larger context, one that touches on Lewis Carroll, Art Deco, Beardsley and Klimt, the arts and craft movement as expressed in the Roycrofter magazines by Elbert Hubbard, early 20th century print design, and classic children’s literature.

Some critics have expressed rather disparaging comments about Carlson’s Jingle Jangle work. Jeet Heer, in a transcript he assembled from the TOON Treasury discussions published in The Comics Journal #302 (the latest phone book sized print annual print edition which is, by the way, highly recommended), questions whether Carlson’s comics would work for the anthology: “The art is lovely, but I’ve always found his stories a chore to read (too much forced whimsy for my taste).” Heer is speaking for many modern readers, including myself, at times.

It's important to note that Heer was not authoring a formal critical review, but instead participating as a "board" advisor in a free-form discussion with several other historians, writers and cartoonists that formed the creative cauldron from which emerged The TOON Treasury of Classic Children’s Comics, selected and edited by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly and published in 2009 by Abrams ComicArts.

Art Spiegelman replied to Heer’s comment: “I’m positive that Carlson oughta be represented in this anthology – he’s one of the reasons for its existence… I usta be put off by his archness while marveling at his cartooning but have come around to appreciating his singularity and quirkiness: a genyoowine sensibility.”

Heer makes a valuable point that I suspect represents the opinion of many modern readers – viewed through a certain lens, Carlson’s compressed gamesmanship can seem like forced whimsy. In the discussion, Frank Young (comics historian and co-author of the Eisner-Award winning graphic novel, The Carter Family: Don’t Forget This Song) addresses Heer’s point: “I have to be in a certain mood for these stories to charm me. When I’m there – usually in a more slowed down, reflective state – I find them to be quite funny and ingenious.”

Heer's last (published) comment in the exchange suggests that he is beginning to reconsider Carlson for inclusion the Toon Treasury. And, indeed, Carlson's stories richly reward the effort it requires to meet them on their own terms.

“A Genyoowine Sensibility”

George Carlson’s sensibility comes not from comic books, nor from newspaper comics – but instead from a rich mix of early 20th century commercial art, book/magazine illustration, game design, and advertising. Much of Carlson’s work is primarily concerned with appealing to and nurturing the minds of children with an emphasis on stimulating the imagination.

Generally, when we read golden age comic book stories, we have – I think – a predisposition toward a certain context that one could say mainly revolves around the myth of the hero’s journey, issues of morality and justice, and the shadow side of sexuality – a context that is very much alive and well in current American culture.

The “quirky” Carlson’s “genyoowine” sensibility emerges from a completely different context, one that is grounded both in early twentieth century graphic design and in classic children’s literature from Lewis Carroll to Edward Lear to Mark Twain (all of whom Carlson illustrated). What seems quirky in the world of comics is utterly mainstream in the larger world of classic children’s literature. It makes perfect sense, then, that Art Spiegelman said that Carlson’s work was one of the raisons d’etre for the creation of the TOON Treasury, a book intended to frame kid’s comics as part of the continuum of “classic” children’s literature.

The only other early comics work I know of that shares Carlson’s grounding in children’s classics is the late 1930’s comics published by David McKay, who published such literary giants as Shakespeare, Walt Whitman, and Beatrix Potter. Founded in 1882, David McKay’s Philadelphia-based publishing house was rooted in a different context than most comic book publishers based in New York.

They published the first Disney albums in the early 1930s. These books, and their comic book line were edited by Ruth Plumly Thompson, who most famously continued writing the Wizard of Oz series of books after the death of Frank L. Baum, the series’ original author. Ruth Plumly Thompson also discovered the woman cartoonist Marjorie Buell Henderson, who created Little Lulu – a character who had a profound influence on the development of comic books (and, as we've seen, may have had an influence on Carlson).

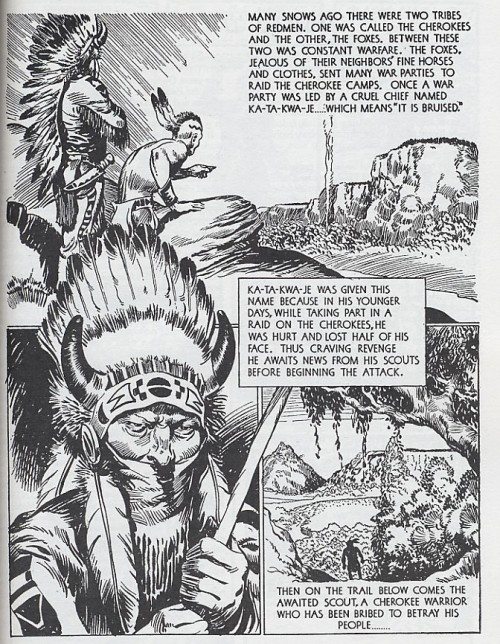

Most notably, in their comics, which were mostly strip reprints, the editors at David McKay fostered the career of the brilliant Jimmy Thompson (apparently no relation to Ruth), who created for McKay two long-running, visually stunning series which offered deep and thoughtful stories of Indians in pre-European settler days. Thus, David McKay came from a tradition of literature and applied that sensibility to comics. It’s no surprise, then, that in 1938 they published one of the first graphic novels, Red Men (by Jimmy Thompson) – a work that combines literary qualities with sequential visual storytelling and could only be possible when created from a grounding in literature – the same grounding that George Carlson shared.

George Carlson, however, was working on his own – a free agent. He didn’t have a time honored publishing house behind him. He probably talked his way into Jingle Jangle (the sing-song title sounds suspiciously like his writing) – probably proposing the series to Eastern Color Printing publisher William Jamieson Pape, who published a puzzle page by A.W. Nugent in his Famous Funnies comics (regarded by many as the first official comic book).

It appears that Carlson tended to conceive of big projects on a regular basis – he designed at least five boxed sets of books. What Carlson lacked in publisher-employer oomph, he made up for in imagination. He wove his sophisticated graphic sensibility, cartooning chops, and his puzzle-crafting skills around stream of consciousness narratives that suddenly felt more at home in Finnegan’s Wake than in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. In so doing, Carlson hit upon something new and different.

It appears that Carlson tended to conceive of big projects on a regular basis – he designed at least five boxed sets of books. What Carlson lacked in publisher-employer oomph, he made up for in imagination. He wove his sophisticated graphic sensibility, cartooning chops, and his puzzle-crafting skills around stream of consciousness narratives that suddenly felt more at home in Finnegan’s Wake than in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. In so doing, Carlson hit upon something new and different.

Carlson’s comic book work offers a dense conversation about the form itself. His pages are filled with innovations, unusual layouts, new ways of showing people and objects, ways of mixing together narration, dialogue and action. At their best, Carlson’s pages offer as many good ideas about making comics as those of Jack Cole or Will Eisner -- and they come from a completely different cultural tributary. There are few, however, that could pull off Carlson’s casual, playful approach. Examining a scan of original art from a Pie-Face Prince story, one sees a looseness in the line coupled with a knowing precision – what Rube Goldberg once called “an open hand.”

A case could be made for Carlson as one of early comics' surrealists, as well. In his Jingle Jangle work, we find a beautiful young woman wearing a sandwich board that reads "Detour." On his cover of Jingle Jangle #6, there's a rather nightmarish scissors bird. His comics are filled with as many shadow figures (often inked entirely in black, living silhouettes) as cutie pies. Even the very structure of Carlson's stories, improvised shaggy dog stories presented in old-fashioned graphic styles, offers congruence that only makes sense in logic-transcending dreams.

In addition, Carlson’s dense visuals offer a provocative conversation about what graphic storytelling could be if it were steeped in a strong design sensibility merged with a sense of the absurd meant to simultaneously delight and challenge readers. The idea of making comics not as something easier to consume than prose alone, but as something just as rich was an ambitious concept in the 1940s.

Carlson was also, like the mathematician storyteller Lewis Carroll, an indefatigable puzzle-maker. A great deal of his pre-comic book career was devoted to designing fanciful puzzles to engage young minds. Thus, the Jingle Jangle stories reflect the idea that there are puzzles and games to play during the reading – which requires, as Frank Young observed, a slower pace. In some ways, Carlson’s free-flowing, puzzle-themed comics anticipate some of the video games of the last 15 years. Moving through the worlds of Animal Crossing, Myst, and Skyrim are, in some ways, very similar to exploring George Carlson’s Pretzelburg and environs (only without the bloodshed).

Carlson's comics are important because they show us what comics rooted in the rich tradition of children's literature look like. Daniel Yezbick has called George Carlson a "twentieth century Lewis Carroll," and that seems right (although "Hans Christian Anderson on LSD" could also apply). From a design standpoint, Carlson's art has the grace and flair of a master craftsman steeped in early 20th century design. His screwball comic book stories are imbued with the freedom of imagination. To fully appreciate and understand George Carlson's work, and the context in which it was created, it is necessary to grasp the full scope of his ambitious and accomplished artistic career -- something to which I sincerely hope this edition of Framed! has made a small contribution.

A George Carlson Bibliography by Paul Tumey

Note: While offering a generally more complete listing than has been available in most places, this list is presumed to be incomplete. There are very likely many more George Carlson works that remain undocumented.

Cartoons, Puzzles and Comics by George Carlson

1913-1932: Various cartoons published in the monthly children’s magazine, John Martin’s Book as well as various magazines such as Judge, Film Fun, and Life. Carlson had a regular feature in John Martin’s Book called Peter Puzzlemaker. He was also the regular puzzle page editor for several other children's magazines, including Youth's Companion and American Girl.

1940-1949 (approximate): Reg’lar Fellers Sunday newspaper comic (ghosting for Gene Byrnes). This period includes the topper comic strip, Dizzie Lizzie (1940-1942) in which Carlson used his own style and zany humor (signed as Gene Byrnes)

1942-1949: Jingle Jangle Comics issues 1-42 (Eastern Color) – Carlson had two stories in most issues, a “Jingle Jangle Tale,” and a “Pie-Face Prince of Old Pretzelburg.”

1946 (Spring and Summer): Puzzle Fun Comics issues 1 and 2 (George W. Dougherty)

1940s: Carlson contributed miscellaneous puzzle and activity pages to various issues of comic books published by Eastern Color Printing, including Famous Funnies and Heroic Comics.

Books by George Carlson

Peter Puzzlemaker (New York, Platt and Munk, 1922)

Draw Comics! Here’s How! (Whitman Publishing, 1933)

Fun For Juniors (New York, Platt and Munk, 1937)

Fun-Time Library (New York, Platt and Munk, 1937) Boxed set, box art by Carlson – also issued as Playtime Library with different box art

Fun-Time Busy Book (New York, Platt and Munk, 1937)

Fun-Time Dot-Pictures (New York, Platt and Munk, 1937)

Fun-Time Drawing (New York, Platt and Munk, 1937)

Fun-Time Games (New York, Platt and Munk, 1937)

Fun-Time Mazes (New York, Platt and Munk, 1937)

Fun-Time Questions (New York, Platt and Munk, 1937)

Fun-Time Play-Book (New York, Platt and Munk, 1937)

Fun-Time Puzzles (New York, Platt and Munk, 1937)

Fun-Time Riddles (New York, Platt and Munk, 1937)

Fun-Time Stunts (New York, Platt and Munk, 1937)

Points On Cartooning and How to Draw Funny Pictures (New York: Treasure Chest Publications, Inc., 1937)

Paint Without Paints (New York, Platt and Munk, 1938) – a series of 10 books with the following subtitles: Animals, Birds, Children of Foreign Lands, In The Stores, Flowers and Designs, Objects, Scenes, Storybook Friends, Toytown Holidays, Transportation

Fun For Juniors (New York, Platt and Munk, 1941)

Fun For Juniors (New York, Platt and Munk, 1941)

Paint Without Paints (New York, Platt and Munk, 1938) Boxed set, box art by Carlson

1001 Riddles (New York, Platt and Munk, 1949)

Loads of Fun (New York, Platt and Munk, 1950)

I Can Draw (Platt and Munk, 1953) Boxed set of 8 books, box art and books by Carlson

Funtime Crossword Puzzles (New York, Platt and Munk, 1955)

Picture Cross-word Puzzles (New York, Platt and Munk, 1958)

The Falcon Book of Riddles (Young Readers Press, 1959)

Jokes and Riddles (New York, Platt and Munk, 1959)

Peter Puzzlemaker: A John Martin Puzzle Book For Little Puzzlers (Dale Seymour Publications, 1991)

Peter Puzzlemaker Returns! More Puzzle for Problem Solvers, compiled by Martin Gardner (Dale Seymour Publications, 1994)

Fun-Time Library (Green Tiger Press, 2008) Reissue of Puzzles, Games, and Drawing

Books Illustrated by George Carlson

Rip Van Winkle and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow – Washington Irving’s Stories Retold by Mary Paterson (New York: John Martin’s House, Inc., 1913) Note: The Goody-Gay Series No. 2

Prince Without a Country by Mary Dickerson Donahey (Barse & Hopkins, 1916)

Snarlie The Tiger (Circus Animal Stories Series) by Howard R. Garris (New York: R.F. Fenno, 1916)

The Magic Stone: Rainbow Fairy Stories by Elizabeth Blanche Wade (New York: Sully and Kleinteich, 1917)

Tobytown by Chandler A. Oakes (New York: Sully and Kleinteich, 1917)

Rubber A Wonder Story by John Martin (New York: United States Rubber Company, 1919)

Jane and the Owl by Gene (Eugenia) Stone (New York: Thomas Y. Cromwell, 1920)

Toni The Little Woodcarver by Johanna Spyri (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1920)

Toni The Little Woodcarver by Johanna Spyri (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1920)

A Treasury of Indian Tales by Clara Kern Bayliss (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1921)

Adventures of Jane by Gene (Eugenia) Stone (New York: Thomas Y. Cromwell, 1921)

Blueberry Bear’s New Home by J.L Sherard (New York: Thomas Y. Cromwell, 1921)

John Martin's Something-To-Do Book (New York: John Martin’s Book House, 1922)

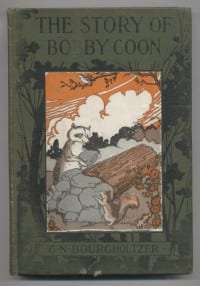

The Story of Bobby Coon by C.N. Bourgholtzer (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1921)

Tiss A Little Apline Waif by Johanna Spyri (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1921)

A Treasury of Eskimo Tales by Clara Kern Bayliss (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1922)

A Treasury of Eskimo Tales by Clara Kern Bayliss (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1922)

Bobby Coon Detective by C.N. Bourgholtzer (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1922)

Trini, the Little Strawberry Girl and the Children’s Christmas Carol by Johanna Spyri (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1922)

John Martin’s Some Fun To Make Book by John Martin (New York: John Martin’s Book House, 1923)

Read to Me More: Book For Little Folk by John Martin (New York: John Martin’s Book House, 1923)

Aesop’s Fables in Rhyme For Little Philosophers by John Martin (John Martin’s Book House, 1924)

Handy Hands Book or Happy Occupations For Little Folks by John Martin (John Martin’s Book House, 1924)

The Romance of Rubber by John Martin (New York: United States Rubber Company, 1924)

The Wayward Man by St John G. Ervine (New York: MacMillan Company, 1927) [dust-jacket]

The Adventures of Toby Spaniel by Alice Crew Gall and Fleming H. Crew (New York: Duffield and Company, 1928)

The Adventures of Toby Spaniel by Alice Crew Gall and Fleming H. Crew (New York: Duffield and Company, 1928)

The Whirlwind by William Stearns Davis (New York: MacMillan Company, 1929) [dustjacket]

A Saga of the Sea by F. Britten Austin (New York: MacMillan Company, 1929) [dustjacket]

Full Measure by Hans Otto Storm (New York: MacMillan Company, 1929) [dustjacket]

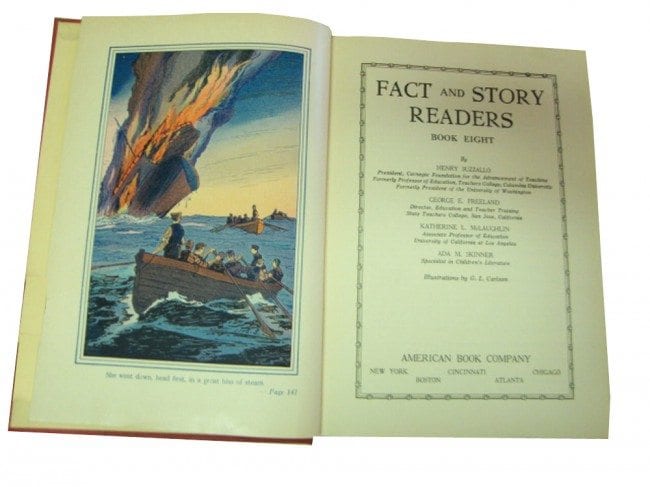

Fact and Story Readers Book Four by Suzzallo, et al (also Book Six, Seven and Eight) (New York: American Book Company, 1931)

Swinton’s Fourth Reader (New York: American Book Company, 1931)

How to Make Sky Pictures: A Star-Sticker Book by John Martin and Roy Youmans (Greenberg, 1935)

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain (Noble and Noble, 1936)

Broncho Apache by Paul I. Wellman (New York: MacMillan Company, 1936) [dustjacket]

Drums In The Forest by Allan Dwight (New York: MacMillan Company) [dustjacket]

Gone With The Wind by Margaret Mitchell (New York: MacMillan Company, 1936) [dustjacket]

Queen Mary: A Book of Comparisons (Cunard White Star Line, printed by Sweeney Litho Co., Inc. in Belleville, NJ, 1936) Note: it’s not known if Carlson also authored this book – no author is listed

Trails of Adventure (The Friendly Hour, Book Four) by Ullin W. Leavell (New York: American Book Company, 1936)

Trails of Adventure (The Friendly Hour, Book Four) by Ullin W. Leavell (New York: American Book Company, 1936)

Treasure Chest of Worldwide Songs (New York: Treasure Chest Publications, Inc., 1936)

Scouting on Mystery Trail by Leonard K. Smith (New York: MacMillan Company, 1937)

Silver Stampede by Neill C. Wilson (New York: MacMillan Company, 1937)

Christmas Song Parade and Pictures to Color (New York: Treasure Chest Publications, Inc., 1938)

How People Work Together by George Earl Freeman (Scribners, 1938) [school reader]

L’il’ Hannibal by Carolyn Sherwin Bailey (New York: Platt and Munk, 1938)

Song Hits of the Gay Nineties: Souvenir of George Jessell's Old New York Village: World's Fair New York 1939 (New York: Treasure Chest Publications, Inc., 1939) [inside page lists copyright as 1935, presumably a mistake]

Stately Timber by Rupert Hughes (New York: Scribner, 1939) [dusjacket]

Uncle Wiggily and the Apple Dumpling by Howard R. Garris (New York: Platt and Munk Company, 1939)

Uncle Wiggily and the Barber by Howard R. Garris (New York: Platt and Munk Company, 1939)

Uncle Wiggily and the Canoe by Howard R. Garris (New York: Platt and Munk Company, 1939)

Uncle Wiggily and the Peppermint by Howard R. Garris (New York: Platt and Munk Company, 1939)

Uncle Wiggily and the Peppermint by Howard R. Garris (New York: Platt and Munk Company, 1939)

Uncle Wiggily and the Red Spots by Howard R. Garris (New York: Platt and Munk Company, 1939)

Uncle Wiggily and the Sleds by Howard R. Garris (New York: Platt and Munk Company, 1939)

Uncle Wiggily and the Snow Plow by Howard R. Garris (New York: Platt and Munk Company, 1939)

Uncle Wiggily Learns to Dance by Howard R. Garris (New York: Platt and Munk Company, 1939)

Uncle Wiggly’s Library by Howard R. Garris (New York: Platt and Munk Company, 1939) [boxed set designed by Carlson]

The Songs of Stephen Foster (New York: Treasure Chest, 1940)

Treasure Chest for the Young Pianist Book One (New York: Treasure Chest Publications, Inc., 1940)

Treasure Chest for the Young Pianist Book Two (New York: Treasure Chest Publications, Inc., 1940)