Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man play a song for me/I'm not sleepy and there is no place I'm going to/Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man play a song for me/in the jingle jangle morning I'll come followin' you (Bob Dylan, 1964)

Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man play a song for me/I'm not sleepy and there is no place I'm going to/Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man play a song for me/in the jingle jangle morning I'll come followin' you (Bob Dylan, 1964)

In the year 8113 A.D., the most remembered cartoonist of our time may not be any of our currently revered comics creators. Not Winsor McCay, George Herriman, Jack Kirby, Robert Crumb, Art Spiegelman, or Chris Ware. As incredible as it may seem, long after the last comic books of our time have crumpled into dust, the cartoonist of our era that People of The Future will dig (perhaps literally) could be a guy named George Carlson -- an under-appreciated, largely overlooked cartoonist, illustrator, game designer, and graphic artist extraordinaire who will finally get his due with the forthcoming release of Perfect Nonsense: The Chaotic Comics and Goofy Games of George Carlson by Daniel Yezbick (Fantagraphics, December 2013). The spirit of George Carlson's playful, surreal world can be seen in everything from Pee-wee's Playhouse to 24-hour comics.

on George Carlson

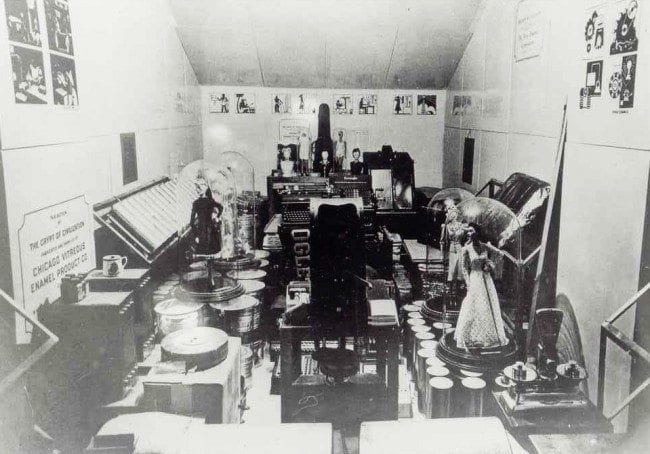

People of the distant future may know about Carlson not because of Yezbick’s book (although it’d be nice to think so), but more likely because of the Crypt of Civilization, a room-sized time capsule that lies underneath what is currently known as Oglethorpe University, in Atlanta, Georgia.

When future human beings pry open the rusty door of the Crypt, they will see plaques on the walls created by George Carlson. The bold, Art Deco graphics on the plaques, barely visible in the photograph (below) of the Crypt’s interior, are presented in a manner that looks back in time to the 2D wall paintings found in ancient Egyptian burial chambers. In 1940, the Crypt’s creator, Oglethorpe University president Dr. Thornwell Jacobs, set the year for the time capsule’s opening at 8113 A.D. - exactly the same amount of years into the future as the number of years spanning backwards in time from 1940 to the oldest known Egyptian tomb.

The Crypt was one of the first and most ambitious projects of its kind. It preserves a summary of Western civilization's achievements and knowledge in science, art, and history. Dr. Jacobs hired commercial artist George Carlson to create the pictograph panels that tell the history of communications and explain how to access the treasures buried in the tomb. The artist that Jacobs chose to create these all-important messages could not have been more appropriate, for much of Carlson’s work is concerned with the tension between the puzzle of the past and the riddle of the future.

Even if Carlson's work is known to the future by virtue of being included in a blast-proof time capsule, it nonetheless merits more attention and study than it has thus far received. If anyone today who studies old comics knows the name George Carlson, it’s because of his 80-odd (and odd would be the operative word) comic book stories that appear in the 42 issues of Jingle Jangle Comics published between 1942 and 1949 (you can read four of these stories online here at Mykal Banta's Big Blog of Kid's Comics).

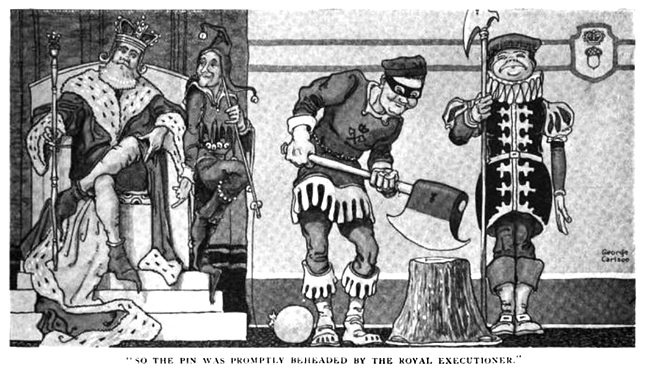

These beautifully cartooned, freewheeling stories sport lyrical titles like “The Sea-Seasoned Sea-Cook and the Heroic Pancake,” “Sleepy Yollo the Bedless Norseman,” and “The Pie-Face Prince of Old Pretzlebug” (a continuing series under the one title). Since 1970, Carlson's Jingle Jangle stories have been admired and respectfully praised by Harlan Ellison, Ron Goulart, Martin Gardner, Dan Nadel, and Art Spiegelman, who said that Carlson was one of the reasons for the existence of The TOON Treasury of Classic Children’s Comics, which he selected and edited with Françoise Mouly in 2009 (see The Comics Journal #302, page 327).

Even though none of Carlson's Jingle Jangle stories are preserved in the Crypt (it was sealed two years before he started creating them), there is, in addition to the pictograph wall plaques, another example of Carlson’s work tucked away in this six-feet-under bouillon cube of western civilization.

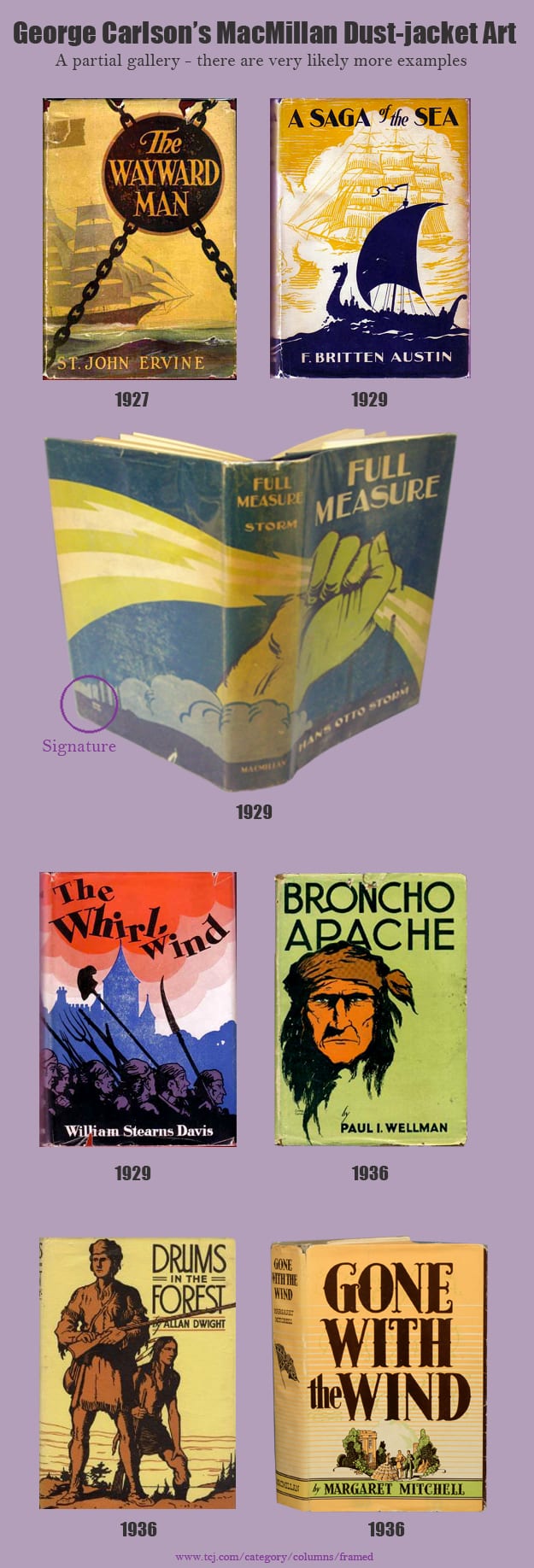

During the time the Crypt of Civilization was built, the best-selling novel in America was Gone With The Wind, by Margaret Mitchell. This epic historical romance about the American Civil War sparked a cultural phenomenon that led to the creation of one of the most famous films in American cinema history. As it happens, much of the novel transpires in – and is about – Atlanta, the very city where the Crypt is located. A sort of time capsule in itself, Gone With The Wind featured, in its first and numerous subsequent hardcover printings, a dust-jacket designed by an artist whose mother worked for General Ulysses S. Grant -- none other than George Carlson.

College English professor Daniel Yezbick, who has authored Perfect Nonsense, the forthcoming book on Carlson, called his Gone With The Wind dust-jacket art “a fusion of both nostalgic romanticism and urbane Modernism.” The cover offers a classic Carlson vignette of the Old South, surrounded by an Art Deco design that would be at home on the front of a streamlined train.

Much of Carlson's prodigious output as one of the busiest graphic artists of the early twentieth century explores the mythic nature of both the past and the future. His Jingle Jangle stories use the trappings of timeless fairy tales to tell stories in a deconstructionist, modernistic manner. Much of his work presents surreal concepts encased in old-fashioned graphic styles. Where the surrealists envisioned fur-covered teacups and melted clocks, Carlson created dishes that spout poetry and clocks run like dogs through the foothills. Carlson -- as it turns out -- was just as capable of creating a vivid image of ancient Greece as he was of depicting the modern engineering marvels of the Queen Mary ocean liner.

How perfect, then, that George Carlson was selected to be the artist for a time capsule.

The Quietly-Quiet Cartoonist and His Long, Wandering Career

George Leonard Carlson (1887-1962) was one of the most accomplished and skillful artists that worked in comics of the 1940s. Although a handful of his comic book stories and children’s books have been reprinted – most famously in the landmark 1982 collection, The Smithsonian Book of Comic Book Comics by J. Michael Barrier and Martin T. Williams -- the full scope of Carlson’s career has remained hidden. This may be because Carlson himself was not much of a self-promoter. For example, there is no known interview with him. So far, only one photograph of him has surfaced, in a place that few would look – a book called From the Wandering Jew to William F. Buckley Jr. by Martin Gardner (Prometheus Books, 2000).

Carlson was more concerned with production than promotion. His work burns with enthusiasm for inventing and perfecting new design ideas. His range and versatility are nothing short of astonishing. The more one digs around, the more of Carlson’s work one finds. Most discoveries are marked with his familiar “G.C.” or “George Carlson” signature tucked away in a corner. It seems that Carlson left his mark in virtually every form of commercial graphic art flourishing in the first half of the twentieth century: magazine cartoons, book illustrations, magazine covers, book covers and dust-jackets, book design, magazine design, games, how-to books, package design, advertising, children’s literature, informational brochures, posters, newspaper comics, and – of course – comic book stories.

It's time to re-frame George Carlson.

Most critics and commentators have written about Carlson as if his seven years of comic book work for Eastern Color from 1942 to 1949 were the primary work of his career, but it turns out this important work is only part of his story. Information on Carlson's long career outside of comics has been largely unknown. This gap has led even the best comics historians to misframe Carlson's contribution to comic books, and his stature as an artist.

For example, in Art Out of Time (Abrams ComicArts, 2006), Dan Nadel’s seminal survey of previously unheralded comics visionaries, George Carlson’s dust-jacket art for Gone With The Wind is characterized as “an unexpected career turn.” In actuality, it appears that Carlson had been designing dust jackets for MacMillan Publishing for about ten years before his GWTW art, and had been illustrating books since 1913. In the last few years, examples of Carlson’s non-comics work have surfaced on the Internet, allowing us to assemble a fuller picture of Carlson’s career.

With the perspective this new knowledge provides, it’s Carlson’s entrance into comic books after nearly thirty years as a successful cartoonist and graphic designer that might be considered to be unexpected.

In fact, in the world of 1940s American comic books, George Carlson is unique. He came to the form at age 55 as a fully developed, mature artist, grounded in children's literature, the craft of book and magazine illustration, and early 20th century commercial art. It was with the supreme skill and confidence forged from a highly successful thirty-year career as an artist that Carlson created the Jingle Jangle stories. At a time when comic book stories were formulaic, repetitive, and machined like products in a factory, George Carlson's explosively imaginative, hand-crafted comics represent a high point in the history of the American comic. It's important to study the career and comics of George Carlson, because his Jingle Jangle stories show us what 1940s comics that evolve from a literary context look like.

The freedom in Carlson's 1940s Jingle Jangle tales anticipates and suggests that comics can be improvisational, like a jazz musician's recording -- an approach that surfaced in the Underground comix of the 1960s and '70s, took root in the 1980s with the self-published and mail-distributed comics of the Newave (particularly with Steve Willis in stories like "The Maze"), and is currently embraced by small press comic artists and the concept of the 24-hour comic.

It is only in the early 21st century, about one hundred years after Carlson began his career, that we can use newly available resources on the Internet to figure out the puzzle of George Carlson.

Biographical Details and First Cartoons

Some biographical details about George Carlson can be gleaned from an article about him that was published on the occasion of his death. The article ran on September 27, 1962 in the Bridgeport Telegram. For the last half of his life, Carlson lived in Bridgeport, Connecticut (which from 1915 to 1936 was also the hometown of another famous cartoonist, Walt Kelly -- whose lyrical sense of the absurd makes one wonder if he and ol' George shared a few hours drawing nonsense comics together on napkins at the local diner).

Carlson’s mother, an emigrant from England, was employed in the home of Ulysses S. Grant just after the Civil War (presumably as a housekeeper). She was among the first people to cross the Brooklyn Bridge on the day it opened in 1883.

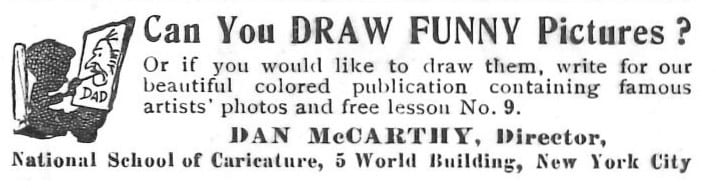

About four years later, George Carlson was born in New York City in 1887. He studied art and cartooning in various schools in New York City, including the National School of Caricature, founded in 1900 by New York World cartoonist Dan McCarthy (Lariat Pete). It may have been McCarthy that influenced Carlson to become a cartoonist. There is some similarity in the jaunty, jocular attitudes of both McCarthy's and Carlson's cartoon figures, although Carlson's renderings are generally considerably more defined.

It appears that Carlson served in World War One in some capacity that is not currently known. In his later years, Carlson was active in an American Legion WWI post (he served as the Post's historian, which shows his interest in the past extended beyond his artwork). He maintained a studio in Fairfield, Connecticut until he moved to Bridgeport sometime after 1940.

A 1930 Federal census of Fairfield yields a few more biographical details. We find Carlson at age 42 living with his wife, Gertrude (31, his partner until his death), and a housekeeper in his own home (valued at $10,000 in 1930) located at 32 Redfield Road in Fairfield, Connecticut. They owned a radio. According to the census, both George's and Gertude's mothers were born in Sweden. Carlson's profession is listed as "artist."

Carlson died in 1962 and his remains were buried in Bridgeport's Mountain Grove Cemetery, which was designed by P.T. Barnum. One can imagine that, had he lived in an earlier era, Carlson could easily have become Barnum’s main ballyhoo artist for his New York based American Museum and sundry publications. Also buried at Mountain Grove are Charles Sherwood Stratton (perhaps the most famous little person in history, known as General Tom Thumb), Stratton's wife Lavinia, and beloved children’s author-illustrator Robert Lawson (who may have known Carlson since they both worked as book cover artists for MacMillan Publishing in the 1930s).

Carlson's art first appears around 1913, in popular national magazines like Judge and Life, and continues in such publications for several years. It's likely that he was also working in various shops and factories at the time to supplement his income.

A useful framework for studying George Carlson's long and varied career is to divide his work into the following six categories:

1. Early cartoons and magazine illustrations

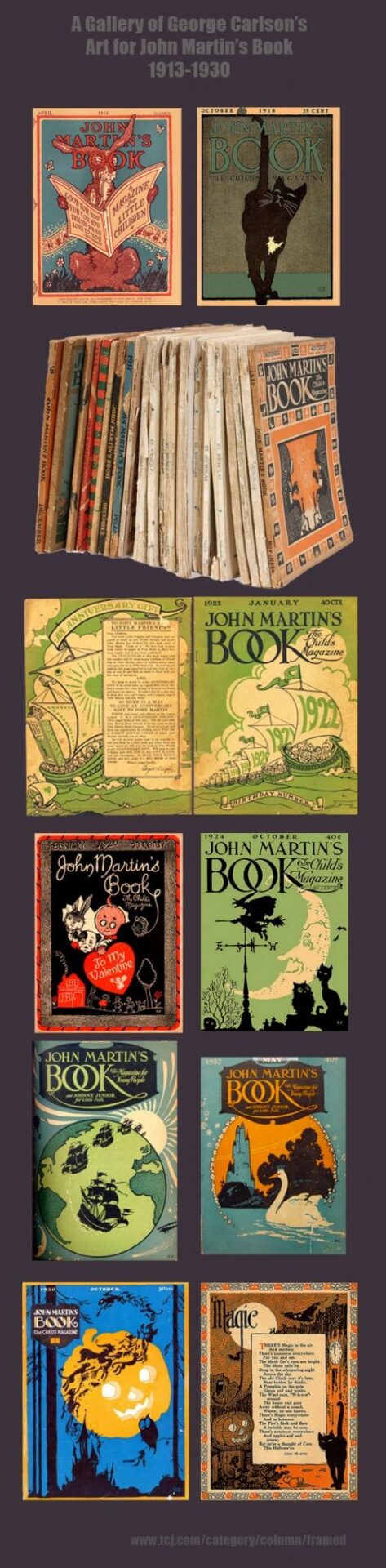

2. Work for John Martin's Book

3. Book covers and illustrations

4. Books authored by George Carlson

5. Newspaper comics

6. Comic book stories

This column, the first of two on Carlson, will look at the first three categories, and the following column (Part 2) will examine the rest.

Seemingly from the start, Carlson possessed great skill and talent, for his first known published works are impressive. For example, his full color, painted cover for the 1913 Christmas issue of Life (the first, more humorous version of the periodical) is confident and assured. Carlson renders a classic Thomas Nast styled Santa Claus in a decorative layout that also functions as a gag cartoon. The image is titled "Conscience" and shows a tiny boy feeling the weight of his imagined misdeeds as he contemplates just how the gargantuan, God-like Santa may decide to judge his worthiness. The cover is a clever and artful design that presents an eye-catching, poster image while also offering context and humor. Carlson's 1922 Printer's Ink Monthly ad (above) describes his style as a combination of "poster and cartoon" and this aesthetic certainly seems to be in play throughout much of his forty-year career.

Carlson contributed a dramatic double-page spread in the September 30, 1915 issue of Life that excelled in both ambition and execution, reflecting the dark power of the first machine-age war.

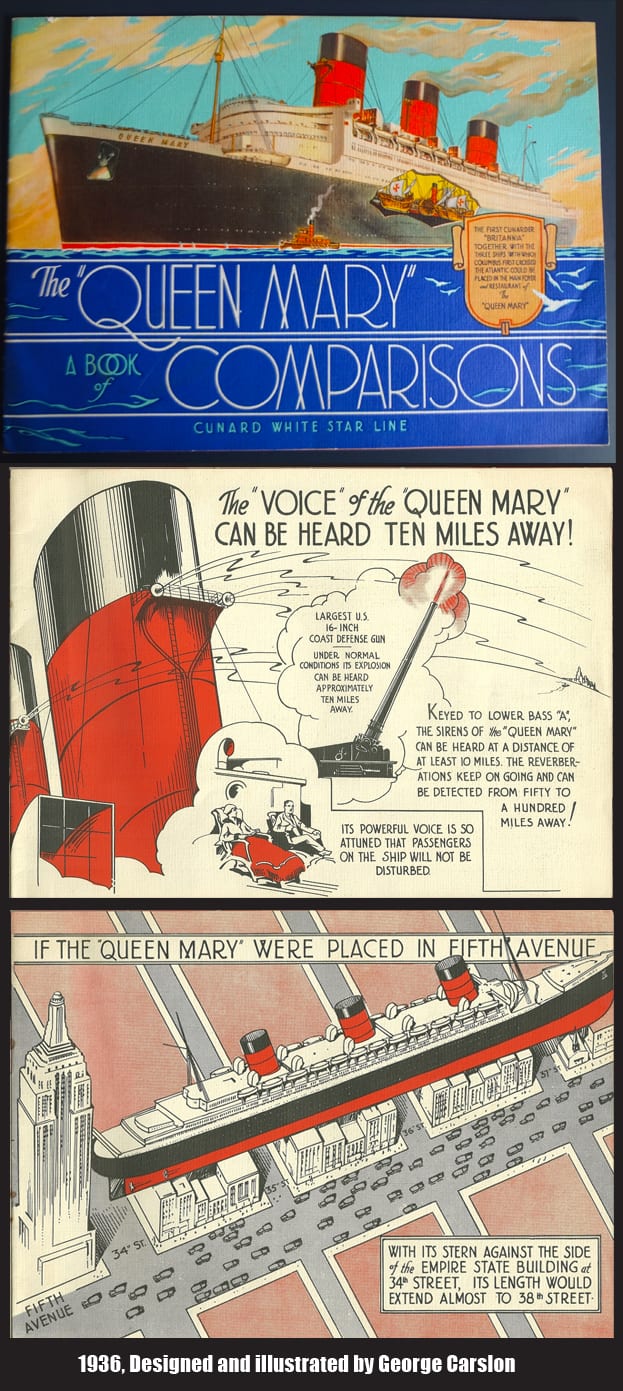

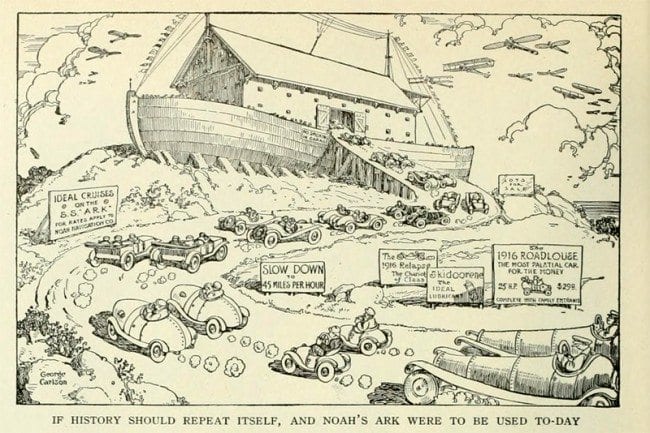

Carlson's line art cartoons appeared regularly on the interior pages and covers of Leslie-Judge publications from approximately 1913 to 1919. These are also impressive, and sometimes revolve around Carlson's experiments in relative scale for effect, such as his Noah's Ark cartoon that depicts 11 pairs of automobiles and a dozen airships, all dwarfed by the massive ark (Carlson would return to this effect in his 1936 pamphlet on the Queen Mary). In it's printed version, this jam-packed, masterful rendering is only five inches wide!

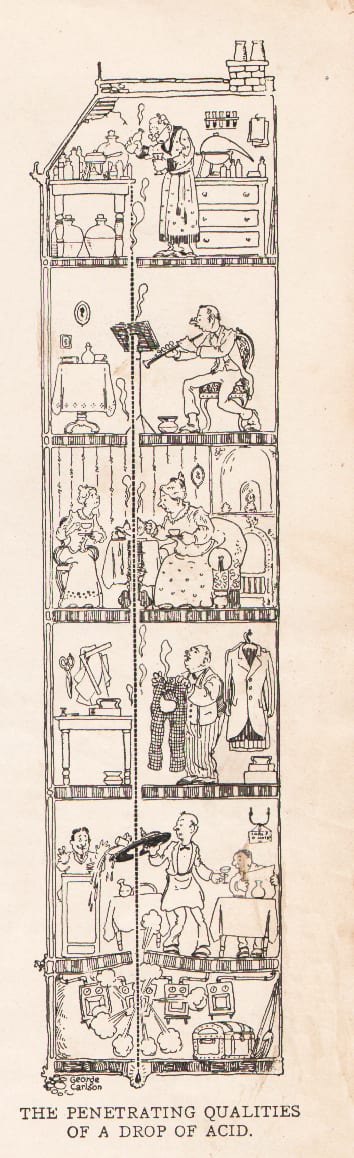

The relatively free and varied format of the Leslie-Judge publications allowed Carlson to experiment with various ways to show sequential graphic scenes, such as his clever multi-tiered building cartoon (circa 1913), "The Penetrating Qualities of a Drop of Acid."

Carlson also gravitated towards storytelling in his Leslie-Judge cartoon work. In "The Wonderful Garden that Jack Owned," (circa 1917), Carlson rather stiffly stretches out a one-note gag in a page that, while beautifully drawn, lacks his whimsical touch.

Movies were an exciting new form of entertainment in Carlson's first decade as a professional cartoonist and commercial artist. Judge and Film Fun both ran a version of movies on paper (silent movies, with title cards), which were often simplified, compressed comic book stories. H. C. Greening created some truly funny cartoons in this series, and may have well been the originator of the concept (see my article on Greening at my Masters of Screwball Comics blog). Carlson took to the format like a duck to water, creating whimsical, off-the-wall stories, such as "The Ambitious Vacuum Cleaner," that anticipate the stream-of-consciousness freedom in his Jingle Jangle comic book work of the 1940s.

"The Ambitious Vacuum Cleaner" is reminiscent of H. M. Bateman's 1920 cartoon, "Possibilities of A Vacuum Cleaner." In both strips, the vacuum becomes a mindless, voracious consumer of every object and living creature in its path. While Carlson ends his comic with the explosive release of the machine's contents, Bateman solipsistically concludes his sequence with the vacuum inhaling its owner and then, itself. For more on Bateman, and the rest of his "Possibilities of a Vacuum Cleaner" cartoon, see my article, "The Comedy of Escalation: H.M. Bateman."

Carlson did several "films on paper" for the Leslie-Judge company. They often embrace the absurd in much the same way as his Jingle Jangle comic book stories. Where many of Carlson's Jingle Jangle stories use a journey as their driving engine, so do some of his "film" parodies, thirty years earlier. In "The Tenderfoot's Revenge," Carlson tells the story of an East Coast salesman who travels to the Wild West.

Not all of Carlson's Leslie-Judge work was light-hearted. Carlson's first years as a professional cartoonist-illustrator occurred during the time of World War One, and he was obliged, as many artists at the time were, to address the great conflict in his work. His full-page 1913 anti-war cartoon for Judge is similar to his 1913 Santa Claus Life cover (above) in that both pieces depict a god-like figure dwarfing humanity.

According to comics historian Ron Goulart, in his Encyclopedia of American Comics (Facts on File, 1990), Carlson drew several covers for Judge. In 1918, Carlson drew Uncle Sam, yet another larger-than-life mythic figure, in a poster-cartoon style for the September 21, 1918 cover of Judge. In this piece, "Ring It Again," Carlson's unique way of combining objects into something new is on display, as a washing machine drying roller is fastened onto the Liberty Bell and used to flatten the German Kaiser.

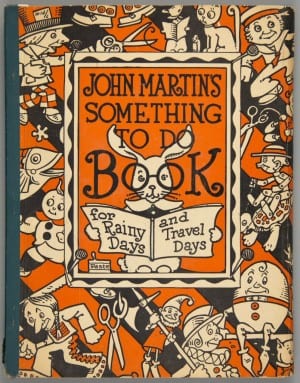

John Martin's Book (1913-1932)

Concurrent with his freelance career as a humor and topical cartoonist with various national magazines, George Carlson also developed a career as an illustrator, artist, and puzzle-maker for children's publications. According to Daniel Yezbick in his splendid essay on Carlson, "Riddles of Engagement," Carlson contributed regularly to several children's magazines from the teens through the twenties, including St. Nicholas, Youth's Companion, Child Life, and the Girl Scouts of America's American Girl magazine, where he was the editor of the puzzle page from 1924 to 1936. Carlson employed a number of styles for his work in this area, from simple, diagrammatic cartoons to lush, textured illustrations in the tradition of Howard Pyle and Maxfield Parrish.

The subject matter of his illustrations for stories by others included classic elements of children's adventure and fantasy stories -- elements that Carlson would use (and in some senses subvert) in his Jingle Jangle stories some 30 years later.

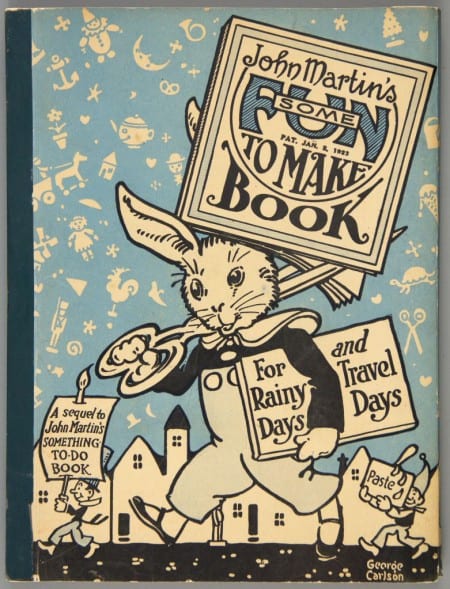

By far, Carlson's most significant work in the field of children's magazines and publishers was his work from approximately 1913 to 1932 with John Martin's Book. Author Martin Gardner, in his 1990 essay "John Martin's Book: A Forgotten Children's Magazine," (reprinted in From the Wandering Jew to William F. Buckley Jr. (Prometheus Press, 2000), writes about the magazine, stating that "in its time it was the most entertaining magazine published in this country for boys and girls aged five to eight. In many ways it was a pioneering publication." Gardner, by the way, was a contributing editor to Humpty Dumpty's Magazine for eight years. I grew up on Gardner's puzzle and games pages that were inspired by Carlson. Gardner wrote, "I took up, so to speak, where Carlson left off."

From 1913, until the magazine's end, in 1933, George Carlson had work in virtually every issue. He provided illustrations (signed and unsigned), spot drawings, and numerous decorative layouts. By Gardner's estimate, Carlson also created at least fifty covers for the magazine. Carlson's JMB covers are, in themselves, outstanding works of graphic design, with patterns, cartoons, and colors combined into delightful visual treats.

It appears that Carlson enjoyed the support and freedom to explore his own ideas about design and creating visual art for children. Carlson, as fellow puzzle-maker Martin Gardner observes, spent much of his career exploring the idea that children’s minds should be – and want to be – engaged. Gardner writes, "The key to this magazine's success was the unfeigned delight taken by its publisher and editor, and by his associate George Carlson."

To fully understand George Carlson, it's important to realize that he and John Martin (whose real name was, incredibly, Morgan von Roorbach Shepard) were passionately devoted for nearly twenty years to developing a series of publications that innovated the idea of active participation, instead of passive reading. To this end, Carlson also created nearly all of the magazine's many puzzles, activities, and riddles. Gardner notes:

"He was responsible for an enormous variety of 'gimmick' pages of a sort never before attempted in a child's magazine. There were pictures that turned into something else when you inverted the page. There were optical illusions, shaped poems, cut-outs that cast startling shadow pictures on the wall, stories with blanks in which children put their own adjective [anticipating Mad-Libs - P.T.]..."

Gardner goes on for another two paragraphs, describing Carlson's numerous novelties and innovations. Of all these, Carlson's regular feature, Peter Puzzlemaker, stands out. In almost every issue of John Martin's Book, the short, squat pragmatic Pilgrim would offer a simple but amusing puzzle.

Many of these were collected into a beautiful book, published in 1922 by Platt and Munk (apparently beginning a long association between Carlson and the publisher that would result in a small library of original children's books). Martin Gardner (who oversaw the publication of two collection of Carlson's Peter Puzzlemaker pages in the early 1990s) praised the collection, saying "No better collection of puzzles for young children was ever published." The hardback book features Carlson's writing and art from cover to cover, with striking color covers, fetching end-papers, and an expert use of spot color. It also plays with the formal aspects of children's book, encouraging young readers to cut out and paste a "lock" in the book onto the answers section in the back, so they wouldn't be tempted to cheat. There is an impressive array of different types of puzzles and activities -- rarely is one form repeated in the book's 128 pages. More than one of the Peter Puzzlemaker pages pays tribute to a classic work of children's literature, such as the puzzle featuring the hookah-smoking caterpillar from Lewis Carroll's Alice In Wonderland (seen in the illustration below).

Gardner characterizes the relationship between Morgan von Roorbach Shepard, the man who called himself "John Martin," and George Carlson as friends. It would be valuable to know the extent to which these two men influenced each other in their work and personal lives. Certainly, some aspects of Shepard's freewheeling, fanciful approach his life and work seem to have made a mark on Carlson's way of making marks. Martin Gardner writes of Shepard, "When he was with children he liked to ask them to make squiggly lines on paper while he jiggled their elbow, then he would add more lines to create what he called a 'quiz-wiz' animal." In two of George Carlson's books on cartooning published in the 1930s, there are pages that suggest and demonstrate the "jiggle line" technique. Clearly, the connection between Shepard and Carlson ran deep. It may be that Shepard's inventive way of entertaining young minds gave Carlson the freedom to approach creating comic book stories as a form of playful improvisation.

Book Covers and Illustrations (1913 - 1940)

In addition to, and concurrent with his magazine work, Carlson also created a wide variety of illustrations and cover art for books authored by others. The list at the end of this article (see "Figuring Out George Carlson,Part 2") contains over fifty citations of books and covers created by George Carlson. It's almost certain that there are more titles, possibly a great deal more, that can be added to this list in time.

The earliest known example of a book illustrated by George Carlson is Rip Van Winkle and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow – Washington Irving’s Stories Retold by Mary Paterson. The book was published by John Martin's Book House, which generated a large quantity of titles that were sold in the back pages of John Martin's Book.

Carlson designed and illustrated a number of books for John Martin from 1913 to the early 1930s, including numerous activity books in which children were encouraged to cut the pages up. As a consequence, many of Carlson's activity books for John Martin are rare and hard to find in unaltered condition.

Carlson appears to have made a pattern out of developing exclusive (that is, in addition to his work with John Martin) relationships with various New York book publishers. From roughly 1916 to 1919, his primary book publisher work was for Sully and Kleinteich. There, he provided art for the whimsical, if somewhat cloying dog fable, Tobytown that included full-page illustrations and charming spot illustrations and colophons.

Carlson also created for Sully and Kleinteich four stunning color plates for The Magic Stone: Rainbow Fairy Stories by Elizabeth Blanche Wade which Martin Gardner called Carlson's "most impressive work."

In the early 1920's, Carlson illustrated and provided cover art for a number of books published by Thomas Y. Crowell. For many of these titles Carlson developed a flat, faux-lithographic illustrative style with a limited color palette that was entirely different than any of his other work.

In the late 1920s, Carlson appears to have found regular work creating a series of bold wraparound dust-jackets in varied styles for MacMillan's line of thick hardcover novels. Currently, I know of seven titles with art by Carlson, including his most well-known work, the dust-jacket art for Gone With The Wind. Interestingly, most of Carlson's dust-jacket covers are signed.

It appears that Carlson also created at least one dust-jacket for another major publisher, Scribners. In 1939, Carlson provided the art for Scribner's Stately Timber by Rupert Hughes.

Thanks to the Smithsonian Institution's American Archives of Art, which houses the Scribners collection, we can see a very rare example of Carlson's original art for a commercial, non-comics project.

In the art, which is clearly signed by Carlson, some background details have been whited out. This was done for the purpose of creating a second version of the art that allowed the printer to print Carlson's trademark quaint townscape in a lighter color, de-emphasizing it and creating the illusion of depth of field.

Carlson also did piecemeal work for a number of different publishers, including his delightful color painting and black-and-white line art for The Adventures of Toby Spaniel by Alice Crew Gall and Fleming H. Crew (New York: Duffield and Company, 1928), a book that even readers today list as among their favorite childhood reads.

One of Carlson's most interesting and graphically impressive illustration projects was his 1936 advertising booklet for the Cunard White Star Line, Queen Mary: A Book of Comparisons. An illustrated book proclaiming the glories of the RMS Queen Mary, one of the largest passenger ships ever built, was a perfect fit for George Carlson. From his monolithic portrayals of ships in magazines to book covers, Carlson had demonstrated a primary fascination with massive ships (and later, trains and planes) in his work, as well a keen sense of drama in scale. Carlson's art for this book is a mini-masterpiece of Art Deco design in the service of advertising, with it's thin, precise lines and streamlined layouts. Carlson's talent for rendering the relative scale of things was never better suited than in these pages that magically convey the majestic enormity of the vessel.

1936 appears to have been a peak year for Carlson, with the production of his iconic cover for Gone With the Wind and his masterful Queen Mary booklet. This was also the year he illustrated Noble and Noble's edition of Mark Twain's Adventures of Tom Sawyer. It's interesting to step back and consider these three works, made in the same year. GWTW and Twain's stories offer romantic backward glances to a time and place long lost (in contrast to Huckleberry Finn, Twain's Tom Sawyer books while funny, are not as bitingly satirical). The other major 1936 work by Carlson, Queen Mary: A Book of Comparisons, manufactures a love poem to modern engineering and monumentally-scaled design. Part of the invisible appeal of Carlson's work exists in the tension between the pull of the past and the drive of the future. In their own ways, all three works as packaged and presented by George Carlson are intoxicating fantasies that say something about American culture in the 1930s.

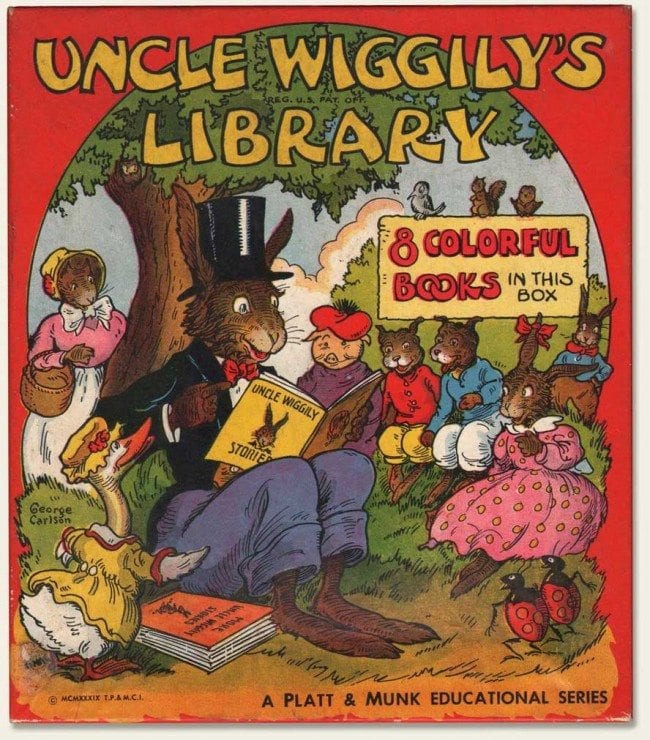

Carlson's last major work as a book illustrator, his Uncle Wiggly series, succumbs entirely to the romantic past. In 1939, Platt and Munk published eight books in the Uncle Wiggily series, all richly festooned with color covers, color and line art illustrations by Carlson. Though the art for these books seems timeless, these were reissues of books already charmingly illustrated by others, including Lansing (Lang) Campbell, who also created a syndicated Uncle Wiggily Sunday comic strip. The bushy-tailed, long-eared character hops back in time to the 1910s, when author Howard Garris began penning stories about him for publication in newspapers. Interestingly, one of the first books George Carlson illustrated, was Garris' Snarlie The Tiger (New York: R.F. Fenno, 1916). It probably didn't occur to either gentleman in 1916 that they would cross paths again three decades later, when Carlson's books would introduce the character to new generations (I had a set of Uncle Wiggly books -- 1960s reprints of Carlson's editions -- when I was a child. I was fascinated by the nightmarish intensity of Carlson's illustrations in Uncle Wiggily and the Snow Plow).

As we study Carlson's career and begin to fill in some of the missing gaps, a portrait of a committed, successful graphic artist emerges. Carlson's love of cartooning informs much of his illustrative work, and it seems clear that his work with John Martin influenced his long devotion to creating engaging and entertaining materials for young minds. In the second half of this piece, (Part 2) I'll look at Carlson's own books, his virtually unknown newspaper comic strip work, and his subsequent comic book work. I'll also present a bibliography of Carlson's work in the next installment of Framed! -- be there or be square!